Nezame no toko

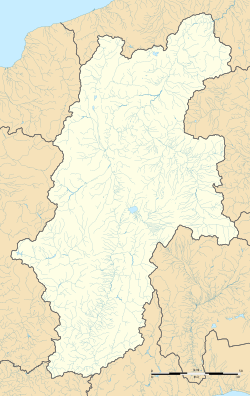

Nezame no toko (寝覚の床), meaning "Bed of Awakening"[1] is a scenic spot located in Japan, located in Agematsu, Kiso District, Nagano Prefecture. It is one of Japan's nationally designated places of scenic beauty.

Overview

One onomatological explanation is that it was so named "Bed of Awakening" because the stunning view stimulated even drowsy onlookers and made them wide awake.[1][2] There are natural formations made from eroded granite rock, that have been said to resemble the shapes of lions, or lotus flower, etc.[1][3]

Alternately, folk tradition says that the name derives from Urashima Tarō experiencing an "awakening" here, that is, the sensation that everything in his life up to then was as if in a dream.[4][lower-alpha 1]

It was selected as one of nationally designated places of scenic beauty in Nagano.[5]

There used to be rapid currents that created the formation, but the water level has lowered, exposing more of the granite formation underwater.[6]

History

There have been waka poetry composed on the Kiso scenery while traveling the Nakasendō that employed "nezame" as keyword (utamakura).[7]

Rinsenji

The Rinsenji in Agematsu stands on a cliff overlooking the strange rock scenery of Nezame no toko.[8] According to the engi (story of the origin) of temple, which stands nearby overlooking the scenery, Rinsenji originally enshrined the Benten statue which local legend said Urashima left behind.[lower-alpha 2][9]

The temple totally burnt down in 1864, except for the Benten-dō (statue hall), and rebuilt the following year. A new main hall, restored to its original appearance was erected in 1971.[3][10] The surviving Benten-dō structure was completed 1712 under the auspices of Tokugawa Yoshimichi, fourth daimyo lord of the Owari domain.[11]

There is also the Urashima-dō, which is a distinctly separate structure.[12] It has stood on top of the tokoiwa ("Bed Rock").[13][14]

The temple's treasure hall houses a fishing pole, alleged to have belonged to Urashima.[14]

Mikaeri no okina

According to folk tradition, there resided in the hamlet of Nezame an old man name Mikaeri no okina (三返りの翁) who provided wonder-medicine to the folk.

The noh play Nezame (『寝覚』) from the late Muromachi Period[lower-alpha 3] is based on this tradition.[15][16]

In the Noh play, the Emperor of Japan during the Engi Era hears of the elixir of longevity, and sends a messenger from court to investigate. The old man reveals himself to be an avatar of the Yakushi Nyorai, calling himself "Medicine-master" (Iwō-butsu 医王仏), and presents the medicine. It is explained that he has lived at Nezame no toko for a thousand years, and has rejuvenated himself three times with the medicine, earning the name Mikaeri meaning "thrice reverted".[16][15]

Urashima Tarō legend

―Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Fukushima-juku, 69 stations of the Kiso-kaidō).

Although this is in the mountainous terrain of Kiso and far from any ocean, there has arisen a local tradition associating the spot with Urashima Tarō, the man who went to the Dragon Palace beyond the sea.

One of the oldest known records indicating local association of this scenic spot with Urashima Tarō is the mention of the so-called Urashima-ga-tsuri-ishi ("Urashima's fishing stone") by Zen priest Takuan in his travelogue Kisoji kikō ki.[18]

Kaibara Ekken also says in his Kisoji no ki (1685) that he witnessed the "Nezame no toko where Urashima fished," but he is skeptical about Urashima ever visiting this area.[18]

According to the Nezame Urashima-dera ryaku-engi (寝覚浦嶋寺略縁起) or story of the founding of Rinsen-ji,[lower-alpha 2] Urashima Tarō had returned from the Dragon Palace (Ryūgū-jō) with there gifts: the "jeweled hand box" (tamatebako), a Benzaiten statue, and a book of knowledge entitled the Manpōshinsho (万宝神書). After traveling various parts of Japan, he settled in a beautiful village by Kiso River. He lived here many years fishing for leisure, while peddling the medicine he had learned to conjure using the esoteric book. One day while storytelling to the villagers about the Dragon Palace, he opened his box, and turned into a 300-year old man. On the 1st year of Tenkei (938) he disappeared from the face of the earth.[19][20]

The Ryaku-engi has gone through many reprints, with the oldest surviving being the revised print of 1756,[21][lower-alpha 5] However, the gist of the legend is thought to have been established earlier, from the near-modern period.[19]

From some point in local tradition,[lower-alpha 6] The Mikaeri no okina and Urashima Tarō came to be seen as the same personage.[22] The Ryaku-engii also states that Urashima earned the moniker 見かへりの翁 (Mikaeri no okina, "Old man of compensation") for being the provender of the magical drug to the villagers.[23]。

An old, pre-Takemoto jōruri called Urashima Tarō was written with this Agematsu area as its setting.[24]

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Walter Weston wrote that Urashima, the Rip van Winkle of Japan had woken up from a long slumber,[2] but Urashima did not enter such a long sleep as van Winkle did.

- 1 2 Although the work is entitled Nezame Urashima-dera ryaku-engi which seems to be about a temple of a different name, the text explicity declares the place was named "Nezame-yama Rinsen-ji",

- ↑ There are records of this being performed in1595 and 1596, etc.[15]

- ↑ It is actually six-miles south of Fukushima that Agematsu, the nearest station to Nezame no toko is located.[2] But the artist is nevertheless alluding to Nezame no toko.[17]

- ↑ At the point of Torii's paper, she thought the 1848 edition to be the oldest.[19]

- ↑ Acoording to Torii, by the Genroku era (1688–1704).

References

- citations

- 1 2 3 The Ministry of Railways (1933), An official guide to eastern Asia (revised ed.), p. 126

- 1 2 3 Weston (1896), pp. 44–45.

- 1 2 Wilson (2015), p. 137.

- ↑ Hama, Mitsuo (はまみつを), ed. (2006), Shinshū no minwa denshō shūsei - Chūshin hen 信州の民話伝説集成 中信編 [Shinano Province folktale tradition collection - Central Shinano], Issosha, p. 398

- ↑ MLIT国土交通省河川局 (2007), Kisogawa suikei no ryūiki oyobi kasen no gaiyō (an) 木曽川水系の流域及び河川の概要(案) (PDF), p. (2) - 24 (17MB file)

- ↑ Hiroshima University Institute of Geology (2015). "Ichi nichi me: Nezame no toko (Nagano-ken) kengaku" 1日目 寝覚の床(長野県)見学 [day 1, Nezame no toko (Nagano) sighting trip]. 巡検ガイド (Spotchecking guide). Retrieved 2017-09-29.

- ↑ Kiso River Lower Stream Office, MLIT Chubu Regional Bureau (2007), "Kimama ni journey Nagano-ken Agematsu-machi" 気ままにjourney 長野県上松町 (PDF), Kisso, 62, retrieved 2017-09-30

- ↑ Wilson (2015), p. 136.

- ↑ Torii (1992), pp. 37–38

- ↑ Kiso Kyōikukai & Kyōdokan (1981), p. 230.

- ↑ Hayashi (2009), p. 110, timeline.

- ↑ Sawa (1981), p. 38.

- ↑ Masaoka, Shiki (1902), Dassai shooku haiwa 獺祭書屋俳話 [edition=3rd expanded], Kobunkan, pp. 173–174

- 1 2 Rurubu (2016), Rurubu Kiso Ina Enakyō Takao るるぶ木曽伊那恵那峡高, p. 41,

浦島堂へは大きな床岩を登る (To [reach] Urashima-dō you climb the large Toko-iwa ("Bed Rock").

(in Japanese) - 1 2 3 Torii (1992), p. 39-40.

- 1 2 Anesaki, Masaharu (1942), "Shinto Ideas as seen in the Noh Plays", Proceedings of the Imperial Academy, 18 (7): 329– (in Japanese)

- ↑ Hayashi, Kouhei (2009), "Shinkirō to Urashima Taro: kaijō no imēji to sono shūhen" 蜃気楼と浦島太郎―海上の龍宮のイメージとその周辺・覚書― [Mirages and the Urashima Legend] (PDF), 苫小牧駒澤大学紀要, 20: 25,

国芳..「福島」は..木曽の山の中で浦島太郎が描かれる所以は、寝覚床があるからである ([Regarding] Kuniyoshi['s].. "Fukushima".. the reason Urashima Tarō is depicted in Kiso's mountainous terrain is due to Nezame-no-toko)

(in Japanese) - 1 2 Torii (1992), pp. 36–37.

- 1 2 3 Torii (1992), pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Wilson (2015), pp. 139–141.

- ↑ Hayashi (1999), p. 89.

- ↑ Torii (1992), p. 40.

- ↑ Torii (1992), pp. 37–38, 40.

- ↑ Torii (1992), pp. 31–35.

- Bibliography

- Hayashi, Kouhei (林晃平) (1999), "Urashimadera Ryakuengi no henbō wo meguri" 浦島寺略縁起の変貌をめぐり [Three Texts of Urashimadera-Ryakuengi conserved in the Former Kampukuji] (PDF), Bulletin of Tomakomai Komazawa University, 1: 89–102 (in Japanese)

- Kiso Kyōikukai; Kyōdokan (1981), Kiso, p. 230 (in Japanese)

- Sawa, Fumio (沢史生) (1981), Kiso rekishi sanpo 木曽歴史散歩, Kiso Kyōikukai (in Japanese)

- Torii, Fumiko (島居フミ子) (1992), "Kiso ni yomigaetta Urashima Tarō" 木曾に蘇った浦島太郎 [Urashima Tarō revived in Kiso] (PDF), Nihon Bungaku, Japan Women's University: 32–43 (in Japanese)

- Weston, Walter (1896), Mountaineering and Exploration in the Japanese Alps, J. Murray, pp. 44–45

- Wilson, William Scott (2015), Walking the Kiso Road: A Modern-Day Exploration of Old Japan, Shambhala Publications, pp. 135–141

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nezame no Toko. |