Nestor Lakoba

| Nestor Lakoba | |

|---|---|

|

Нестор Лакоба (Russian) Нестор Лакоба (Abkhazian) | |

| |

| 1st Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Soviet Socialist Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia | |

|

In office February 1922 – 28 December 1936 | |

| Preceded by | Post created |

| Succeeded by | Avksenty Rapava |

| Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Abkhaz ASSR | |

|

In office 17 April 1930 – 28 December 1936 | |

| Preceded by | Post created |

| Succeeded by | Alexei Agrba |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1 May 1893 Lykhny, Sukhum Okrug, Kutais Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died |

28 December 1936 (aged 43) Tbilisi, Georgian SSR, Soviet Union |

| Citizenship | Soviet |

| Nationality | Abkhazian |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

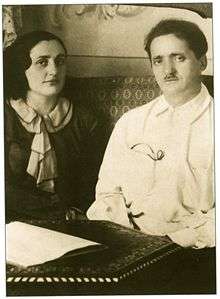

| Spouse(s) | Sariya Lakoba |

| Children | Rauf Lakoba |

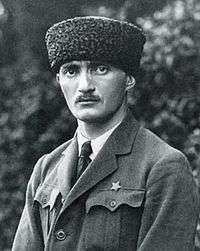

Nestor Apollonovich Lakoba (Russian: Не́стор Аполло́нович Лако́ба; Abkhazian: Нестор Аполлонович Лакоба; 1 May 1893 – 28 December 1936) was an Abkhaz Communist leader. Lakoba helped establish Bolshevik power in Abkhazia in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, and served as the head of Abkhazia after its incorporation into the Soviet Union in 1921. While in power, Lakoba saw that Abkhazia was initially given autonomy within the USSR as the Socialist Soviet Republic of Abkhazia. Though nominally a part of Georgia with a special status of "union republic", the Abkhaz SSR was effectively a separate republic, made possible by Lakoba's close relationship with Joseph Stalin. This also ensured that during the era of collectivization, Abkhazia was largely spared, though in return Lakoba was forced to accept a downgrade of Abkhazia's status to that of an autonomous republic within the Georgian SSR.

Immensely popular in Abkhazia due to his ability to resonate with the people, Lakoba maintained a close relationship with Stalin, who would frequently holiday in Abkhazia during the 1920s and 1930s. This relationship saw Lakoba become rivals with one of Stalin's other confidants, Lavrenti Beria, who was in charge of the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic. During a visit to Beria in Tbilisi in December 1936, Lakoba was poisoned, allowing Beria to consolidate his control over Abkhazia and all of Georgia. Rehabilitated after the death of Stalin in 1953, Lakoba is revered as a national hero.

Early life

Youth and education

Nestor Lakoba was born in the village of Lykhny, Abkhazia to a peasant family, one of three sons along with Vasily and Mikhail. His father, Apollo, died three months before his birth, with Mikhail Bgazhba, who would serve as the First Secretary of Abkhazia, writing that Apollo was shot for opposing the nobles and landowners in the region.[1] Lakoba's mother remarried twice, but both husbands died.[2] From ages 10 to 12 Lakoba attended a parish school in New Athos, followed by a further two years of schooling in Lykhny.[3] He then entered the Tiflis Seminary in 1905.[4] Disinterested in religious study, Lakoba was frequently caught reading books banned by the school authorities.[5] Physically unimpressive, Lakoba was nearly totally deaf, and used hearing aids throughout his life.[2][6] This became a well-known feature of Lakoba, and he would be jokingly referred to as the "Deaf One" by Joseph Stalin.[7]

In 1911 he was expelled for revolutionary activity and moved to Batum, then a major port for exporting oil out of the Caucasus, where he taught privately and studied for the gymnasium exam.[8] It was in Batum that Lakoba first became acquainted with the Bolsheviks, working with them from the autumn of 1911 and officially joining in September 1912.[9] He became involved with disseminating propaganda amongst the workers and peasants in the city and throughout Adjara, the local region, and began to refine his ability to relate to the masses at this time.[10] Discovered by the police, he was forced to leave Batum in 1914, so moved to Grozny, another major oil-based city in the Caucasus, and continued his efforts to spread Bolshevik propaganda amongst the people.[8] Lakoba continued studying in Grozny, passing his examinations in 1915, and the following year enrolled in law at Kharkov University in what is now Ukraine; the ongoing First World War and its effect on Abkhazia led him to quit his studies and return home after only a short time.[11]

Early Bolshevik activities

Back in Abkhazia Lakoba took up a position in the Gudauta region helping to build a railway to Russia, while continuing to spread Bolshevik propaganda to the workers.[12] The 1917 February Revolution, which ended the Russian Empire, saw the status of Abkhazia became contested and was unclear.[13] A peasant assembly was created to govern the region, and Lakoba was elected as a representative of Gudauta.[8] Bgazhba notes that his ability to mingle with the people of the region, and his speaking abilities made him an ideal choice as representative.[14] Lakoba gained wider notability across Abkhazia by helping to establish "Kiaraz" (mutual support in Abkhaz), a peasant brigade that would later help consolidate Bolshevik control.[15]

Lakoba was the lead Bolshevik in Abkhazia when the Revolution began in 1917, based in Gudauta in the north of Abkhazia, and opposed the Mensheviks, who were centered on Sokhumi.[16] On 16 February 1918, Efrem Eshba, an Abkhaz Bolshevik, aided by Russian sailors from warships docked at Sukhumi, overthrew the Abkhaz People's Council (APC) that had provisionally controlled Abkhazia since November 1917.[17] This coup only lasted five days, as the warships departed, leaving little support for the Bolsheviks, and the APC resumed control of Abkhazia.[18] In April Lakoba joined Eshba in again overthrowing the APC, holding power for 42 days before the forces of the Georgian Democratic Republic, with the help of Abkhaz anti-Bolsheviks, regained control over Abkhazia, which they regarded as an integral part of Georgia. Both Lakoba and Eshba would flee to Russia, and not return to Abkhazia until 1921.[17] Georgia never fully maintained control of the region, leaving the APC to rule it until the Bolshevik invasion of 1921.[19]

In the autumn of 1918 Lakoba was ordered to return to Abkhazia, in order to attack the Mensheviks from their rear positions. He was captured during this time and imprisoned in Sokhumi, though released early in 1919 due to public opposition.[20] That April he was offered the post of police commissioner of the Ochamchira District, which he accepted and used as a means to spread Bolshevik propaganda. When the Menshevik-backed central authorities became aware of this Lakoba again left Abkhazia, staying in Batumi for a few months. While there he was elected the deputy chairman of the Sokhumi district party committee.[21] Lakoba also led several operations near Batumi that hindered the ability of the White movement (opponents of the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War) in the Caucasus, further improving his image amongst the Bolshevik leadership.[22]

Leader of Abkhazia

Establishment as leader

Lakoba returned to Abkhazia after it had been occupied by Bolshevik Russia, as part of its conquest of Georgia. Along with Eshba and Nikolai Akirtava, Lakoba was one of the signatories on a telegram to Vladimir Lenin announcing the formation of the Socialist Soviet Republic of Abkhazia (SSR Abkhazia) which was initially allowed to exist as a full union republic.[23] A Revolutionary Committee (Revkom), formed and led by Eshba and Lakoba in preparation for the Bolshevik occupation, took control of Abkhazia.[24] The Revkom resigned on 17 February 1922, and Lakoba was unanimously elected the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, a body that was formed that day, thus effectively the head of Abkhazia.[25] He would hold this post until 17 April 1930, when the Council was abolished and replaced by a Presidium of the Central Executive Committee, though Lakoba would retain the top position.[8] Though held in high regard by his fellow revolutionaries, Lakoba never held a significant role within the Communist Party and refused to attend any meetings, as the Abkhaz Party was simply a branch of the Georgian Party, instead using his patronage network to establish himself.[26][2]

Lakoba in power

Uncontested as the leader of Abkhazia, Lakoba had such control that it was jokingly referred to as "Lakobistan."[2] Long a friend of several leading Bolsheviks, including Sergo Orjonikidze, Sergei Kirov, and Lev Kamenev, it was his relationship with Stalin that was most important to Lakoba's rise to power.[27] Stalin was fond of Lakoba as they shared several features: both were from the Caucasus, grew up without their fathers (Stalin's father had moved away for work when Stalin was young), and attended the same seminary school. Stalin also liked that Lakoba was a good marksman, and liked his work during the Civil War.[28] Familiar with Abkhazia from his revolutionary days, Stalin had a dacha built in the region and vacationed there throughout the 1920s, and would joke "I am Koba, and you are Lakoba" ("Я Коба, а ты Лакоба" in Russian; Koba was one of Stalin's pseudonyms as a revolutionary).[6][29] However it was the role Lakoba played in Stalin's own rise to power that cemented his status as a close confident: when Lenin died Leon Trotsky, the only serious rival to Stalin for the leadership, was in Sukhumi for health reasons. Lakoba ensured Trotsky stayed isolated and thus absent from the immediate aftermath of the Lenin's death and funeral, thus helping Stalin consolidate his power.[26][30] To this extent he was invited to the Thirteenth Party Congress in Moscow, held in May 1924. There Lakoba further acquainted himself with Stalin, who was in the process of consolidating his power, and made a lasting impression.[31]

Lakoba used his relationship with Stalin to benefit himself and Abkhazia. Aware that the Abkhaz would be marginalized within the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (Georgian SSR), he sought to keep Abkhazia as a full union republic, though ultimately had to concede to the status of "treaty republic" within Georgia, a status never fully clarified.[32][33] In this regard Abkhazia, as a part of the Georgian SSR, joined the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (a union of the Georgian, Armenian, and Azerbaijanian SSRs) when it was founded in 1922.[34] Lakoba avoided going through Party channels, which meant dealing with reluctant officials in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, and instead used his connections to go directly to Moscow.[27] He also took advantage of the korenizatsiia policies, implemented throughout the 1920s that benefited ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union, to promote his own confidants, often ethnic Abkhaz.[35] In recognition of his leadership, Lakoba was awarded the Order of Lenin on 15 March 1935, along with Abkhazia itself, though the ceremony was pushed back until the next year in order to coincide with the fifteenth anniversary of the establishment of the Bolsheviks in Abkhazia. In December 1935, while in Moscow, Lakoba was also given the Order of the Red Banner, in recognition of his efforts during the Civil War.[36]

As a leader Lakoba proved to be very popular with the populace, which contrasted with other ethnic minority leaders across the Soviet Union, who were usually distrusted by the locals and regarded as representatives of the state.[37] He visited the villages of Abkhazia, and as Bgazhba wrote, "Lakoba wanted to be familiar with the living conditions of the peasants."[38] Unlike other Bolshevik leaders Lakoba was quiet and elegant, not prone to shouting to make his point.[2] He was especially known for his accessibility to the people: a 1924 report by the journalist Zinaida Rikhter said that:

"In Sukhum, only in the reception room of the presidium can we but get an idea of the peasant identity of Abkhazia. To Nestor, as the peasants simply call him one on one, they come with any little thing, bypassing all official channels, in certainty that he will hear them out and make a decision. The head of Abkhazia, Comrade Lakoba, is loved by the peasants and by the entire population."[39]

Development of Abkhazia

_(b).jpg)

A proponent of developing Abkhazia, Lakoba oversaw massive industrialization policies like the establishment of a coal mining operation near the town of Tkvarcheli, though they did not have a large impact on the overall economic strength of the region.[40][41] Other projects included building new roads and railways, the drainage of wetlands as a preventative measure against malaria, and increased forestry.[42] Agriculture was also given prominence, particularly tobacco; by the 1930s Abkhazia supplied up to 52 percent of all tobacco exports from the USSR.[43] Other agricultural products, including tea, wine, and citrus fruits—especially tangerines—were produced in large quantities, making Abkhazia one of the most well-off regions in the entire Soviet Union, and considerably richer than Georgia.[44] The export of these resources turned the region into "an island of prosperity in a war-ravaged Caucasus".[45] Education was also a major issue for Lakoba, who oversaw the formation of many new schools throughout Abkhazia: aided by the korenizatsiia policies that promoted local ethnic groups, multiple schools teaching in Abkhaz were opened in the 1920s, as well as schools in Georgian, Armenian, and Greek.[46][47]

Lakoba was also determined to maintain ethnic harmony in Abkhazia, a demographically diverse region.[48] The ethnic Abkhaz only constituted roughly 25–30% of the population during the 1920s and 1930s.[49] There were also significant numbers of Georgians, Russians, Armenians, and Greeks.[48] This often saw Lakoba outright ignore Marxian class theory, as he protected former landowners and nobles in order to keep peace in Abkhazia, and ultimately led to a 1929 report that called for him to be removed from power, with only Stalin stopping this, though criticizing Lakoba for his mistake of "seeking support in all layers of the population" (which was contrary to Bolshevik policy.[50]

The implementation of collectivization across the Soviet Union, which began in 1928, proved to be a major issue for both Abkhazia and Lakoba. Traditional Abkhaz agricultural practice had seen farming conducted by individual households, though assistance from other families and friends was frequent.[51] Historian Timothy Blauvelt has written that Lakoba deferred for the first two years of collectivization and used a variety of measures to do so, like the relative "backward" condition of Abkhazia, his concern for the people and thus his support base, and even his relationship with Stalin.[52][53] Lakoba's refusal to introduce collectivization led to further issues between him and the Abkhaz Party, which was only stopped by Stalin, who rebuked the Party for "not taking into consideration the specific particularities of the Abkhazian situation, imposing sometimes the policy of mechanically transferring Russian forms of socialist construction onto Abkhazian soil."[52]

By January 1931 the Party had forced the issue, sending activists across Abkhazia to coerce peasants into collectives.[52] There was large-scale protests in January February against the issue. Lakoba proved unable to fully stop collectivization, though he was able to mollify some of the most extreme measures, and stopped deportations.[54][55] However, as the Abkhaz historian Stanislav Lakoba (no relation) has argued, with Stalin now firmly in control in Moscow he was no longer interested in leniency towards Lakoba or Abkhazia; in exchange for the relaxed introduction of collectivization, Lakoba had to acquiesce to Abkhazia losing it's status as a "treaty republic."[56] As a result, on 19 February 1931 Abkhazia was downgraded into an Autonomous Republic, the Abkhaz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which was more firmly under Georgian control.[57] The move was unpopular in Abkhazia and saw public protests, the first large-scale protests in Abkhazia against the Soviet authorities.[58]

Rivalry with Beria

Lakoba was also influential in the rise of Lavrentiy Beria. It was on Lakoba's suggestion that Stalin first met Beria, an ethnic Mingrelian who was born and raised in Abkhazia.[59] Beria had served as the head of the Georgian secret police since 1926, and with the support of Lakoba he was named the Second Secretary of Transcaucasia, as well as First Secretary of Georgia in November 1931, and again promoted to First Secretary of Transcaucasia in October 1932.[60] Lakoba supported Beria's rise because he felt that as a native of Abkhazia, and young, Beria would be obedient to Lakoba, whereas previous officials had not been. That Beria lacked any direct access to Stalin was also important, as it meant Lakoba could maintain his strong relationship with Stalin.[61] Blauvelt also suggests that Lakoba wanted Beria in power to help quash the 1929 accusations that he was abusing his power in Abkhazia; while report presented to the Central Committee in 1930 exonerated Lakoba, it was mainly due to lack of evidence and the intercession of Stalin. With Beria, who still headed the Georgian secret police, in a position of influence, he could heavily influence any future investigations into Lakoba.[62]

Once in this position, Beria began to both undermine Lakoba and gain closer access to Stalin.[62][63] Lakoba grew to despise Beria, and sought to discredit him, apparently telling Ordzhonikidze that Beria once said that Ordzhonikidze "would have shot all the Georgians in Georgia if it was not for [Beria]," and discussing the rumour that Beria had worked as a counter-informant in Azerbaijan in 1920.[62] Amy Knight suggests that another source of tension may have been the longstanding animosity between Mingrelians and Abkhazians; during the Second Five-Year Plan, which began in 1933, Beria had tried to initiate the settlement of large numbers of Mingrelians into Abkhazia, though it was ultimately blocked.[64] The relationship between the Beria and Lakoba deteriorated as each tried to become closer to Stalin, Lakoba retained his close relationship.[65]

In 1933, Beria apparently staged an event to try and win the support of Stalin, who was staying at his dacha in Gagra, in the north of Abkhazia.[62][66] On 23 September, Stalin went for a short boat ride on the Black Sea, which his dacha overlooked, using a small boat, the Red Star, which was not equipped for the open waters.[67] The passengers, which included Stalin, Beria, Kliment Voroshilov, and a few others, intended to go up the shore a bit for a few hours for a picnic.[68] As they approached their destination, near the town of Pitsunda, three rifle shots landed in the water near the boat, coming from either the lighthouse or border post on shore. Though none of the shots were close, Beria would later recount that he covered Stalin's body with his own.[69] Initially Stalin joked about the incident, though he later sent someone to investigate, and received a letter from the border guard who apparently took the shots, asking for forgiveness and explaining he thought it was a foreign vessel.[69] Beria's own investigation suggested the policy to shoot at unknown ships could be blamed on Lakoba, though Beria was told by his superiors to drop the matter, with rumours of Beria staging the entire incident to frame Lakoba spread.[69]

Another source of contention between Beria and Lakoba concerned the publication, in 1934, of the book Stalin i Khashim (Сталин и Хашим in Russian; Stalin and Khashim). It chronicled a period of Stalin's life as a revolutionary, when he hid with a villager, Khashim Smyrba, near Batumi in 1901–1902, and showed Stalin as someone who was close to the people, which Stalin enjoyed hearing. Ostensibly written by Lakoba, it was praised by Stalin, who enjoyed the description of Khashim, "simple, naïve, but honest and devoted."[70] In response Beria began a project to chronicle Stalin's entire time as a revolutionary in the Caucasus.[70] The finished work, On the Question of the History of the Bolshevik Organizations in the Transcaucasus (К вопросу об истории большевистских организаций в Закавказье) greatly falsified Stalin's role in the region and was printed in Pravda in a serial, and made Beria well-known across the entire Soviet Union.[71]

Beginning in 1935, Stalin made overtures to Lakoba to move to Moscow and replace Genrikh Yagoda as the head of the NKVD, the Soviet secret police.[72] Lakoba turned down the offer in December 1935, content to stay in Abkhazia.[73] This outright refusal of an offer from Stalin only led to trouble for Lakoba, as his goodwill began to dissipate.[74] After Stalin asked Lakoba again in August 1936 to take over the NKVD, only to be turned down, a new law was implemented, "On the Correct Typeface Names of Settlements," which saw toponyms across Abkhazia have to adopt Georgian language spelling rules, rather than Abkhaz or Russian as it had been previously (for example the capital, known as Sukhum in Russian officially became Sokhumi).[75] Lakoba, who had refused to issue license plates in Abkhazia until they switched the location from "Georgia" to "Abkhazia" recognized that this was a deliberate move by Beria and Stalin to undermine him, and took caution. He began to lobby Stalin to transfer Abkhazia from Georgia into the nearby Krasnodar Krai within Russia, though was rebuffed each time.[73] On Lakoba's final visit to Moscow and Stalin, he brought the topic up one final time, and again complained about Beria.[75]

Death

As Lakoba was incredibly popular in Abkhazia, Beria was unable to easily remove him.[76] Instead, on 26 December 1936 Lakoba was summoned to Party headquarters in Tbilisi by Beria, ostensibly to stand before the Party and explain his recent interactions with Stalin.[75] Beria had Lakoba over for dinner the next day, and fed him fried trout for dinner, a favorite of Lakoba's.[77] It is likely that Beria poisoned Lakoba at this time.[76] They attended the opera after the dinner, watching the play "Mzetchabuki" (მზეჭაბუკი; "Sun-boy" in Georgian).[77] During the performance Lakoba first showed signs of his poisoning, and returned to his hotel room, where he died early the next morning.[78] Officially Lakoba was said to have died of a heart attack, though a previous medical examination in Moscow had showed he had arteriosclerosis (thickening of the arteries), cardiosclerosis (thickening of the heart), and erysipelas (skin inflammation) in the left auricle that had led to his hearing loss.[79] His body was returned to Sukhumi, though notably all the internal organs (which could have helped identify the cause of death), were removed.[80]

Though Stalin was not directly responsible for the death of Lakoba, it is likely he played a role, as Beria would not have been able to kill someone as prominent as Lakoba without Stalin's approval.[64] It is also notable that though telegrams of condolence came from various leading officials throughout the Soviet Union, Stalin himself did not send one.[77] Nor did Stalin look into what role, if any, Beria had played in Lakoba's death.[79] Instead Lakoba was accused of national deviation, of having helped Trotsky, and of trying to kill both Stalin and Beria.[81]

Despite the immediate denunciations, Lakoba was laid in state in Sukhumi for two days, followed by an elaborate state funeral on 31 December, with 13,000 people attending, though not Beria.[79] Initially buried in the Sokhumi Botanical Garden, Lakoba's body was moved the first night to St. Michael's Cemetery in Sukhumi, where it stayed for several years before being returned to its original place.[82] According to Nikita Khrushchev's memoirs, Beria had Lakoba's body exhumed and burned on the pretext that an "enemy of the people" did not deserve burial in Abkhazia; this was possibly done to hide evidence of poisoning.[83]

Aftermath

In the months that followed Lakoba's death, members of his family were implicated on charges against the state. His two brothers were arrested on 9 April 1937, with his mother and Sariya arrested on 23 August of that year.[84] A trial of thirteen members of Lakoba's family was conducted between 30 October and 3 November 1937 in Sokhumi, with charges including counter-revolutionary activities, subversion and sabotage, espionage, terrorism, and insurgent organization in Abkhazia. Nine of the defendants, including Lakoba's two brothers, were shot the night of 4 November.[85] Rauf, Lakoba's 15-year-old son, tried to speak to Beria, who visited Sokhumi to view the start of the trial, and was promptly arrested as well. Sariya was taken to Tbilisi and tortured in order to extract a statement implicating Lakoba, but refused, even after Rauf was tortured in front of her.[86] Sariya would die in prison in Tbilisi on 16 May 1939.[87] Rauf was sent to a labour camp, and was eventually shot in a Sokhumi prison on 28 July 1941.[88]

With Lakoba dead, Beria effectively took control of Abkhazia and implemented a policy of Georgianization.[89] Abkhaz officials were purged, ostensibly on charges of trying to assassinate Stalin.[90] The greatest difference was the policy to settle thousands of ethnic Mingrelian farmers across Abkhazia, displacing the ethnic Abkhaz and reducing their overall share of the population.[89] While Lakoba had strived for ethnic harmony, Beria abandoned this policy and favoured his fellow Mingrelians, fulfilling a project first in 1933 at the start of the second five-year plan.[90][91]

Legacy

During the remainder of the Stalinist era Lakoba was seen as an "enemy of the people," though after 1953 he was rehabilitated.[92] A statue was built in his honour in the Sukhumi botanical garden in 1959, and he was subsequently honoured in Abkhazia.[93] In 1965 Mikhail Bgazhba, who was the First Secretary of the Abkhaz Communist Party from 1958 until 1965, wrote a short biography of Lakoba, largely rehabilitating him.[94] In Abkhazia he is revered as a hero, and associated with the first major success of culture and development.[8]

A museum dedicated to the life of Lakoba was established in Sukhum, though it was burnt down during the 1992–1993 war in Abkhazia.[95] Plans to rebuild a new museum was announced by the de facto Abkhaz government in 2016.[96] Lakoba's collected papers were smuggled out of Abkhazia shortly after his death and were initially kept hidden in Batumi before being given to Princeton and Stanford Universities.[97]

References

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, pp. 7–8

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kotkin 2017, p. 137

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 8

- ↑ Bolshaya sovetskaya entsyklopediya 1973, p. 122

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 9

- 1 2 Blauvelt 2007, p. 208

- ↑ Kotkin 2017, p. 504

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kuprava 2015, p. 463

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 11

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 12

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 14

- ↑ Blauvelt 2007, p. 206

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 16

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 19

- ↑ Saparov 2015, p. 43

- 1 2 Blauvelt 2014, p. 24

- ↑ Welt 2012, pp. 207–208

- ↑ Lakoba 1990, p. 63

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, pp. 27–28

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, pp. 28–29

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, pp. 29–31

- ↑ Blauvelt 2012b, p. 82

- ↑ Saparov 2015, p. 48

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 39

- 1 2 Blauvelt 2007, p. 207

- 1 2 Blauvelt 2012a, p. 236

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 106

- ↑ Kotkin 2017, p. 137

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, pp. 97–99

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 101

- ↑ Kotkin 2017, p. 138

- ↑ Saparov 2015, pp. 51–60

- ↑ Hewitt 1993, p. 271

- ↑ Blauvelt 2012a, p. 237

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 108

- ↑ Blauvelt 2012b, pp. 83–84

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 45

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 99

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, pp. 43–44

- ↑ Anchabadze & Argun 2012, p. 90

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 44

- ↑ Suny 1994, p. 268

- ↑ Zürcher 2007, pp. 120–121

- ↑ Rayfield 2004, p. 95

- ↑ Blauvelt 2012a, p. 250

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 38

- 1 2 Blauvelt 2012a, p. 235

- ↑ Müller 1998, p. 231

- ↑ Blauvelt 2012b, pp. 84–85

- ↑ Blauvelt 2012b, p. 85

- 1 2 3 Blauvelt 2007, p. 211

- ↑ Blauvelt 2012b, p. 86

- ↑ Blauvelt 2007, pp. 211–212

- ↑ Blauvelt 2012b, pp. 86–103

- ↑ Lak'oba 1998, p. 94

- ↑ Blauvelt 2007, p. 212

- ↑ Lakoba 1995, p. 99

- ↑ Kotkin 2017, pp. 139–140

- ↑ Blauvelt 2007, p. 213

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, pp. 103–104

- 1 2 3 4 Blauvelt 2007, p. 214

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 104

- 1 2 Knight 1993, p. 72

- ↑ Blauvelt 2007, pp. 214–216

- ↑ There are different interpretations of this event: Stanislav Lakoba has suggested one version, while Sergo Beria, Beria's son, has written a different account. See Blauvelt 2007, p. 228, note 65.

- ↑ Kotkin 2017, p. 141

- ↑ Kotkin 2017, pp. 141–142

- 1 2 3 Kotkin 2017, p. 142

- 1 2 Kotkin 2017, p. 214

- ↑ Kotkin 2017, p. 260

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 110

- 1 2 Lakoba 2004, p. 111

- ↑ Blauvelt 2007, p. 216

- 1 2 3 Kotkin 2017, p. 505

- 1 2 Lak'oba 1998, p. 95

- 1 2 3 Lakoba 2004, p. 112

- ↑ Rayfield 2012, p. 352

- 1 2 3 Kotkin 2017, p. 506

- ↑ Hewitt 2013, p. 42

- ↑ Kotkin 2017, pp. 506–507

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 113

- ↑ Khrushchev 2004, p. 188

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, pp. 113–114

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 117

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 118

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 119

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, pp. 120–121

- 1 2 Blauvelt 2007, pp. 217–218

- 1 2 Slider 1985, p. 52

- ↑ Lakoba 2004, p. 116

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, p. 56

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965, pp. 56–57

- ↑ Bgazhba 1965

- ↑ Kuprava 2015, p. 464

- ↑ Yesiava 2016b

- ↑ Yesiava 2016a

Bibliography

- Anchabadze, Yu. D.; Argun, Yu. G. (2012), Абхазы (The Abkhazians) (in Russian), Moscow: Nauka, ISBN 978-5-02-035538-5

- Bgazhba, Mikhail (1965), Нестор Лакоба (Nestor Lakoba) (in Russian), Tbilisi: Sabtchota Saqartvelo

- Blauvelt, Timothy (May 2007), "Abkhazia: Patronage and Power in the Stalin Era", Nationalities Papers, 35 (2): 203–232, doi:10.1080/00905990701254318

- Blauvelt, Timothy (2012a), "'From words to action!': Nationality policy in Soviet Abkhazia (1921–38)", in Jones, Stephen F., The Making of Modern Georgia, 1918 – 2012: The first Georgian Republic and its successors, New York City: Routledge, pp. 232–262, ISBN 978-0-41-559238-3

- Blauvelt, Timothy K. (2012b), "Resistance and Accommodation in the Stalinist Periphery: A Peasant Uprising in Abkhazia", Ab Imperio, 3: 78–108, doi:10.1353/imp.2012.0091

- Blauvelt, Timothy K. (2014), "The Establishment of Soviet Power in Abkhazia: Ethnicity, Contestation and Clientalism in the Revolutionary Periphery", Revolutionary Russia, 27 (1): 22–46, doi:10.1080/09546545.2014.904472

- Bolshaya sovetskaya entsyklopediya (1973), "Nestor Lakoba", Bolshaya sovetskaya entsyklopediya (Great Soviet Encyclopedia) (in Russian), Vol. 14, Moscow: Bolshaya sovetskaya entsyklopediya, p. 122

- Hewitt, B.G. (1993), "Abkhazia: a problem of identity and ownership", Central Asian Survey, 12 (3): 267–323, doi:10.1080/02634939308400819

- Hewitt, George (2013), Discordant Neighbours: A Reassessment of the Georgian-Abkhazian and Georgian-South Ossetian Conflicts, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, ISBN 978-9-00-424892-2

- Khrushchev, Nikita (2004), Khrushchev, Sergei, ed., Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev: Volume I, Commissar (1918–1945), translated by Shriver, George, University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, ISBN 0-271-02332-5

- Knight, Amy W. (1993), Beria: Stalin's First Lieutenant, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-01093-5

- Kotkin, Stephen (2017), Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941, New York City: Penguin Press, ISBN 978-1-59420-380-0

- Kuprava, A.E. (2015), "Lakoba, Nestor Apollonovich", in Avidzba, V.Sh., Абхазский Биографический Словарь (Abkhaz Biographical Dictionary) (in Russian), Sukhum: Abkhaz Institute of Humanitarian Studies

- Lakoba, Stanislav (1990), Очерки Политической Истории Абхазии (Essays on the Political History of Abkhazia) (in Russian), Sukhumi, Abkhazia: Alashara

- Lakoba, Stanislav (1995), "Abkhazia is Abkhazia", Central Asian Survey, 14 (1): 97–105, doi:10.1080/02634939508400893

- Lak'oba, Stanislav (1998), "History: 1917–1989", in Hewitt, George, The Abkhazians: A Handbook, New York City: St. Martin's Press, pp. 67–88, ISBN 978-0-31-221975-8

- Lakoba, Stanislav (2004), Абхазия после двух империй. XIX-XXI вв. (Abkhazia after two empires: XIX–XXI centuries) (in Russian), Moscow: Materik, ISBN 5-85646-146-0

- Müller, Daniel (1998), "Demography: ethno-demographic history, 1886–1989", in Hewitt, George, The Abkhazians: A Handbook, New York City: St. Martin's Press, pp. 218–231, ISBN 978-0-31-221975-8

- Rayfield, Donald (2012), Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia, London: Reaktion Books, ISBN 978-1-78-023030-6

- Saparov, Arsène (2015), From Conflict to Autonomy in the Caucasus: The Soviet Union and the making of Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno Karabakh, New York City: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-41-565802-7

- Slider, Darrell (1985), "Crisis and Response in Soviet Nationality Policy: The Case of Abkhazia", Central Asian Survey, 4 (4): 51–68, doi:10.1080/02634938508400523

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation (Second ed.), Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-25-320915-3

- Welt, Cory (2012), "A Fateful Moment: Ethnic Autonomy and Revolutionary violence in the Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918–1921)", in Jones, Stephen F., The Making of Modern Georgia, 1918 – 2012: The first Georgian Republic and its successors, New York City: Routledge, pp. 205–231, ISBN 978-0-41-559238-3

- Yesiava, Badri (28 December 2016a), Историк: тело Нестора Лакоба было сожжено в районе Маяка в Сухуме (Historian: Nestor Lakoba's body was burned in the Mayak area in Sukhum) (in Russian), Sputnik News, retrieved 9 September 2018

- Yesiava, Badri (28 December 2016b), Музеи Нестора Лакоба и Баграта Шинкуба появятся в Абхазии (Museums of Nestor Lakoba and Bagrat Shinkub will appear in Abkhazia) (in Russian), Sputnik News, retrieved 9 September 2018

- Zürcher, Christoph (2007), The Post-Soviet Wars: Rebellion, Ethnic Conflict, and Nationhood in the Caucasus, New York City: New York University Press, ISBN 978-0-81-479709-9