Nansemond

_(2).jpg) Members of the Nansemond tribe at First Landing State Park in 2007 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

Enrolled members 200 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Virginia | |

| Languages | |

| English, Algonquian (historical), Nottoway | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Traditional Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Chickahominy, Mattaponi, Nottoway |

The Nansemond are a Native American tribe recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia, along with ten other Virginia Indian[1] tribes.[2] On January 12, 2018, they gained federal recognition through the passage of the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017, which included recognition for five other tribes.[3]

Most members of the tribe live in the Suffolk/Chesapeake, Virginia area, along the southern border of the state.[4] At the time of European encounter, the historic Nansemond tribe spoke one of the Algonquian languages.[5]

History

The Nansemond were members of the Powhatan chiefdom, which was a loose confederacy of about 30 tribes, estimated to have numbered more than 20,000 people in the coastal area of what became Virginia.[5] They lived along the Nansemond River, an area they called Chuckatuck.[5] In 1607, when English people arrived to settle at Jamestown, the Nansemond were initially wary.[6]

In 1608, the English raided one of the Nansemond towns, burning houses and destroying canoes to force the people to give corn to the settlers.[4] Captain John Smith and his men demanded 400 bushels of corn or threatened to destroy the village, remaining canoes, and houses.[5] The tribe agreed, and Smith and his men left with most of the tribe's corn supply. They returned the following month for the rest, which left the tribe in bad shape for the winter. Relations between the English and the Nansemond deteriorated further in 1609 when the English tried to gain control of Dumpling Island, where the head chief lived and where the tribe's temples and sacred items were kept.[4] The English destroyed the burial sites of tribal leaders and temples. Houses and religious sites were ransacked for valuables, such as pearls and copper ornaments, which were buried with the bodies of leaders.[5] By the 1630s, the English began to move into Nansemond lands, with mixed reactions.[6]

Marriage of John Basse and Elizabeth

John Basse, an early settler in Virginia, married Elizabeth, the daughter of the King of the Nansemond Nation. She was baptized into the Anglican Church and they married on August 14, 1638. Bass was born 7 September 1616; he died 1699.[7]

They had eight children (Elizabeth; John; Jordan; Keziah; Nathaniel; Richard; Samuel; William). They became related to the Coppedge/Coppage/Coppidge Family through intermarriage.

Some Nansemond claim descent from this marriage.[5] Based on her research, Dr. Helen C. Rountree says that all current Nansemond descend from this marriage, making the tribe a family affair.[6]

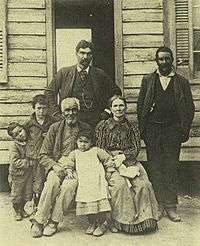

The photo at left shows members of the Weaver and Bass families, ca. 1900:

William H. Weaver is sitting; Augustus Bass is standing behind him. The Weaver family were indentured East Indians (from modern-day India and Pakistan) who were free in Lancaster County by about 1710. By 1732 they were "taxables" [note: free blacks (generally free people of color) and Indians had to pay a tax in Virginia and North Carolina] in Norfolk County and taxable "Mulatto" landowners in nearby Hertford County, North Carolina by 1741.

The Nansemond were affected by English colonial pressures in the 17th century and split apart. Those who were Christianized and had adopted more English customs stayed along the Nansemond River as farmers. The other Nansemonds, known as the “Pochick,” warred with the English in 1644, fled southwest to the Nottoway River, and had a reservation assigned them there by the Virginia colony. By 1744 they had ceased using the reservation and gone to live with the Nottoway Indians [note: this was an Iroquoian-language tribe] on another reservation nearby... The Nansemond sold their reservation in 1792 and were known as "citizen" Indians.[6]

Nansemond today

Today, the Nansemond have about 200 tribal members.[8] As a "citizen tribe", they gained recognition by Virginia in 1984.[9] The disruption of wars and loss of records in Virginia made it difficult for them to provide the extensive documentation and proof of historical continuity needed to gain federal recognition in the 20th century. The current Chief is Barry "Big Buck" Bass.[8]

They hold monthly tribal meetings at the Indiana United Methodist Church (which was founded in 1850 as a mission for the Nansemond). The tribe co-hosts an annual pow wow in June in Chesapeake, and has an annual pow wow every year in August. The tribe has also operated a museum and gift shops.[4]

Mattanock

The Nansemond are one of the few state-recognized tribes in Virginia that have not purchased land for their tribe. But, they are trying to get the city of Suffolk to give up 100 acres (0.40 km2) of an 1,100-acre (4.5 km2) riverfront park. They want to use this land to reconstruct Mattanock, a town of their ancestors. They plan to attract tourists by demonstrating their heritage.[8] The tribe has enlisted the help of Helen C. Rountree, whose research helped identify Mattanock Town's location. The village would use archaeological and other research to ensure that structures, such as longhouses, to be built on the site had the proper historic dimensions.[10]

They have been trying to obtain the area for more than 10 years as a place to put a cultural center, the Mattanock village, tribal offices, pow wow grounds and a meeting place. The Suffolk task force on the project, made up mostly of non-Indians, has supported giving the site to the Nansemond. Suffolk's mayor, E. Dana Dickens III, has publicly supported this project as well. She said of the proposed museum and village, "It certainly can be a big part of Suffolk's tourism." The tribe has had to supply detailed plans for the project, including drawings. They have also had to submit documentation to the Mattanock Town task force that explains the type of non-profit foundation that will be created once the deed to the land is given to the tribe.[10]

In November 2010, the Suffolk City Council agreed to transfer this land back to the Nansemond. In June 2011, everything stalled as a result of concerns the tribe had with the proposed development agreement sent by the city to the tribal association in December. As a result, the project has been delayed and remains in legal limbo.[11]

In August 2013 the City of Suffolk transferred Nansemond ancestral lands back to the tribe.[12] In November 2013 members of the Nansemond Tribe gathered at the site of Mattanock Town and blessed the land.[13]

Federal recognition

The Nansemond and other Virginia tribes had not been accorded federal recognition by the US government until 2018. A bill to recognize six tribes was introduced into both houses of Congress. It covered the following: Chickahominy Indian Tribe; Eastern Chickahominy Indian Tribe; Upper Mattaponi Tribe; Rappahannock Tribe, Inc.; Monacan Indian Nation; and Nansemond Indian Tribe.[14] In 2009 supporters again proposed the "Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act". By June 2009 the bill passed the House Committee on Natural Resources and the US House of Representatives. A companion bill was sent to the Senate the date after the bill was voted on in the House. That bill was sent to the Senate's Committee on Indian Affairs. On October 22, 2009 the bill was approved by the Senate committee and on December 23 was placed on the Senate's Legislative calendar.[15][16] The bill had a hold placed for "jurisdictional concerns" by Senator Tom Coburn (R-OK), who urged they apply through the BIA.

But the Virginia tribes have lost valuable documentation because of the state's passage of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, requiring classification of all residents as white or black (colored). As implemented by Walter Plecker, the first registrar (1912–1946) of the then-newly created Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics, records of many Virginia-born tribal members were changed from Indian to "colored" because he decided some families were mixed race and was imposing the one-drop rule.[17] After more delays, the bill was finally passed in January 2018, and six tribes in Virginia gained federal recognition.

References

- ↑ "A Guide to Writing about Virginia Indians and Virginia Indian History" Archived 2012-02-24 at the Wayback Machine., Virginia Council on Indians, Commonwealth of Virginia, updated Aug 2009, accessed 16 Sep 2009

- ↑ "Virginia Tribe" Archived 2012-07-11 at Archive.is, Virginia Council on Indians, Commonwealth of Virginia, updated Aug 2009, accessed 16 Sep 2009

- ↑ "Bill Passes to Give 6 VA Native American Tribes Federal Recognition", WTVR, 12 January 2018; accessed 16 February 2018

- 1 2 3 4 Karenne Wood, ed., The Virginia Indian Heritage Trail Archived 2009-07-04 at the Wayback Machine., Charlottesville, VA: Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Waugaman, Sandra F. and Danielle-Moretti-Langholtz, Ph.D. We're Still Here: Contemporary Virginia Indians Tell Their Stories, Richmond, VA: Palari Publishing, 2006 (revised edition)

- 1 2 3 4 Dr. Helen C. Rountree, "Nansemond History", Nansemond Tribal Association, accessed 16 Sep 2009

- ↑ Sermon Book of John Bass, owned by the Nansemond Tribe.

- 1 2 3 Joanne Kimberlain, "We're Still Here," The Virginian-Pilot, June 7–9, 2009: Print.

- ↑ Dr. Helen C. Rountree, "Powhatan History", Nansemond Tribe Website, 2009, accessed 16 Sep 2009

- 1 2 Bobby Whitehead, "Nansemond Indians seek to reconstruct Mattanock Town", Indian Country Today, accessed 16 September 2009.

- ↑ "Mattanock Town stalls – The Suffolk News-Herald". suffolknewsherald.com. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "Nansemond Indian Tribe Reclaims Native Land in Suffolk". publicnewsservice.org. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "Tribe blesses land – The Suffolk News-Herald". suffolknewsherald.com. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2003, 108th Congress bill S.1423", introduced by then-Sen. George Allen (R-VA), not enacted.

- ↑ "H.R. 1385, Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act", GovTrack.us

- ↑ "Statement of Governor Kaine Submitted to the United States Senate Committee on Indian Affairs" Official Site of the Governor of Virginia

- ↑ ABP. "Baptist executives urge federal recognition of Virginia tribes". Baptist News Global – Conversations that Matter. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

External links

- Nansemond Indian Tribal Organization

- Virginia Council on Indians

- "Virginia Indian Heritage Program", Virginia Foundation for the Humanities