Long-fingered bat

| Long-fingered bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Vespertilionidae |

| Genus: | Myotis |

| Species: | M. capaccinii |

| Binomial name | |

| Myotis capaccinii Bonaparte, 1837 | |

| |

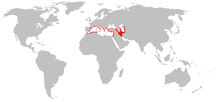

| Distribution of long-fingered bat | |

The long-fingered bat (Myotis capaccinii) is a species of vesper bat. It is known from Morocco, Algeria, southern Europe and the Middle East as far east as western Iran and have become regionally extinct in Switzerland.

Physical characteristics

The bat is medium-sized for a vesper bat, with characteristically large feet, and more prominent nostrils than other European Myotis species. Their length range from 47-53mm, and can weigh up to 7-13g.[2] The hind feet of the long-fingered bat can be from 10–13 mm long [3] on which they also have long bristles. Hair is dark grey at the base, with light smoky grey dorsal-side hair and light grey ventral-side hair.

Ecology

M. capaccinii lives in limestone areas, preferably wooded or shrubby terrain near flowing water. Summer and winter roosts are always in caves. They hunt insects, usually aquatic insects, and fish.[4] These cave-dwelling bats are dependent on underground shelters to roost.[5] Due to the reliance M. capaccinii has on foraging over bodies of water, they are also known to dwell in areas which include clutter-free waterways. Rivers wider than 10 m that contain high amounts of riparian vegetation, to prevent the water from becoming too disturbed by wind, are hypothesized to be more preferable to this species due to their "trawling" nature. The calm water provided through these conditions allows the bat to use echolocation more effectively while foraging, rather than the harsh conditions typically noted in other bodies of water.[6] This species has also been found to forage while traveling to their foraging area of choice, effectively allowing themselves to accomplish more on a single trip. Long-fingered bats have different summer and winter roosts in which on average are 50 km apart, but can range up to 140 km.[6]

Population

The current population trend of long-fingered bats is decreasing. Spain's population of long-fingered bats has decreased between 30-50% in the last 10 years, and is less than 10,000 individual bats total. There are only 30 colonies in Spain that are known to contain more than 20 bats. In France, the known population is less than 3,800 individuals. The Bulgarian population of long-fingered bats is around 20,000 individuals. Long-fingered bats are more abundant in the eastern region of their range rather than the western region.[6]

Reproduction

Little is known about this species reproductive cycle. Mating begins in August and could continue until late winter and early spring. Gestation takes six to eight weeks. Maternity roosts are in caves, formed in the summer, with up to 500 females in clusters on the cave roof, where very few males are present. Birth occurs in mid to late June, with only one pup born, which is weaned after approximately four to six weeks.

Threats and Conservation

Threats

The three main threats to all species of bats are, roost disappearance and disturbance, altering of foraging areas and pesticides. The long-fingered bat is largely affected by roost disappearance and disturbance and altering of foraging areas. Tourism is one of the leading causes of the population trend. Many proposals have been made to explain the decrease in the population size. The long-fingered bat strictly depends on underground shelters and the localized extinctions have been caused by disturbance of breeding roosts. Populations in western Europe have been succeptible to the disturbance of habitat and roosts.[7] In France, alteration of Mediterranean rivers have been a factor of the population decreasing. The main prey of M. capaccinii, chironomids, accumulate toxic compounds which lead to possible death in these bats. In Northern Africa, some long-fingered bats have been killed and used for medicinal purposes.[6]

Conservation

Long-fingered bats are protected by national legislation in most of their range states. International legal obligations for protection such as the Bonn Convention and Bern Convention. Long-fingered bats are included in Annex II and IV of EU Habitats and Species Directive, meaning they need special measures for conservation. Fences have been placed in Spain to protect several known colonies. To protect this species from becoming endangered or going extinct, future measures that need to be taken include protection of colonies and water quality improvement.[6] Some have proposed that the depletion of aquifers and alteration of water bodies near roosts should be avoided, and because the species is dependent on clutter-free water and prey availability, that the priority should be protecting large waterways near roosts.[5]

References

- ↑ Paunović M (2016). "Myotis capaccinii". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2016: e.T14126A22054131. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T14126A22054131.en. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ "Long-fingered bat videos, photos and facts - Myotis capaccinii". Arkive. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- ↑ Aizpurua O, Garin I, Alberdi A, Salsamendi E, Baagøe H, Aihartza J (2013-11-27). "Fishing long-fingered bats (Myotis capaccinii) prey regularly upon exotic fish". PLOS One. 8 (11): e80163. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080163. PMC 3842425. PMID 24312200.

- ↑ Aihartza JR, Goiti U, Almenar D, Garin I (2003). "Evidences of Piscivory byMyotis capaccinii(Bonaparte, 1837) in Southern Iberian Peninsula". Acta Chiropterologica. 5 (2): 193–198. doi:10.3161/001.005.0204.

- 1 2 Almenar D, Aihartza J, Goiti U, Salsamendi E, Garin I (2009). "Foraging behaviour of the long-fingered bat Myotis capaccinii: implications for conservation and management". Endang Species Res. 8: 69–78. doi:10.3354/esr00183.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Myotis capaccinii (Long-fingered Bat)". www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- ↑ Guillen A, Ibanez C, Perez JL, Hernandez LM, Gonzalez MJ, Fernandez MA, Fernandez R (1994) Organochlorine residues in Spanish common pipistrelle bats (Pipistrellus pipistrellus). Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 52:231–237.

Further reading

- Aizpurua O, Aihartza J, Alberdi A, Baagøe HJ, Garin I (September 2014). "Fine-tuned echolocation and capture-flight of Myotis capaccinii when facing different-sized insect and fish prey". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 217 (Pt 18): 3318–25. doi:10.1242/jeb.104992. PMID 25013107.

- Hutson, A.M.; Spitzenberger, F.; Aulagnier, S.; Juste, J.; Karataş, A.; Palmeirim, J. & Paunović, M. (2008). "Myotis capaccinii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.3. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 5 Sep 2010.

- Schober W, Grimmberger E (1989). Dr. Robert E. Stebbings, ed. A Guide to Bats of Britain and Europe (1st ed.). UK: Hamlyn Publishing Group. ISBN 0-600-56424-X.