Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army

| Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army | |

|---|---|

|

မြန်မာအမျိုးသား ဒီမိုကရက်တစ် မဟာမိတ်တပ်မတော် Participant in the Internal conflict in Myanmar | |

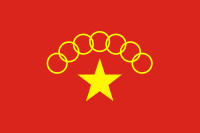

Flag of the MNDAA | |

| Active | 12 March 1989 – present |

| Ideology |

Kokang nationalism Separatism |

| Leaders |

Pheung Kya-shin[1] Yan Win Zhong[2] |

| Area of operations | Kokang Self-Administered Zone, Myanmar |

| Size | 2,000[2]–4,000[3] |

| Part of | Myanmar National Truth and Justice Party |

| Originated as |

|

| Became | Mongko Region Defence Army (split in 1995) |

| Allies | |

| Opponents |

|

| Battles and wars | |

The Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (abbreviated MNDAA; Burmese: မြန်မာအမျိုးသား ဒီမိုကရက်တစ် မဟာမိတ်တပ်မတော်; Chinese: 緬甸民族民主同盟軍; pinyin: Miǎndiàn mínzú mínzhǔ tóngméng jūn), also known as the Myanmar Nationalities Democratic Alliance Army and the Kokang Army, is a communist-inspired armed insurgent group in the Kokang region, Myanmar (Burma). The army has existed since 1989, having been the first one to sign a ceasefire with the Burmese government that lasted for about two decades.[5][6]

History

The army was formed on 12 March 1989, after the local Communist Party of Burma leader, Pheung Kya-shin (also spelled Peng Jia Sheng or Phone Kyar Shin), dissatisfied with the communists, broke away and formed the MNDAA.[7] Along with his brother, Peng Jiafu, they became the new unit in Kokang.[8] The strength of the army is between 1,500 and 2,000 men.[8]

The rebels soon became the first group to agree to a ceasefire with the government troops. Thus the Burmese government refers to the Kokang region controlled by the MNDAA as ‘Shan State Special Region 1’, indicating the MNDAA was the first group in the area of Shan State to sign a cease-fire agreement.[7] After the ceasefire, the area underwent an economic boom, with both the MNDAA and regional Myanmar Armed Forces (Tatmadaw) troops benefiting financially from increased opium harvests and heroin-refining.[9] The area also produces methamphetamine.[10] The MNDAA and other paramilitary groups control the cultivation areas, making it an easy target for drug trafficking and organised crime groups.[10] Peace Myanmar Group is used to launder and reinvest MNDAA's drug profits in the legal economy.[11]

2009 Kokang incident

In August 2009, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army became involved in a violent conflict with Myanamar armed forces. This was the largest outbreak of fighting between ethnic armies and government troops since the signing of the cease-fire 20 years earlier.[12]

As a result of the conflict the MNDAA lost control of the area and as many as 30,000 refugees fled to Yunnan province in neighbouring China.[13]

2015 offensive

On 9 February 2015 the MNDAA tried to retake the Kokang Self-Administered Zone, which had been under its control until 2009, and clashed with Burmese government forces in Laukkai. The skirmishes left a total of 47 Government soldiers dead and 73 wounded.After several months' fierce conflict,Kokang insurgents failed to capture Laukkai.After the incident the government of China was accused of giving military assistance to the ethnic Kokang soldiers.[14]

2017 clashes

On 6 March 2017, MNDAA insurgents attacked police and military posts in Laukkai, resulting in the deaths of 30 people.[15][16]

See also

References

- ↑ Neither War Nor Peace - Transnational Institute

- 1 2 Myanmar Peace Monitor - MNDAA

- ↑ "47 Govt Troops Killed, Tens of Thousands Flee Heavy Fighting in Shan State". irrawaddy.org.

- ↑ Lynn, Kyaw Ye. "Curfew imposed after clashes near Myanmar-China border". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ Ethnic group in Myanmar said to break cease-fire. Associated Press. 28 August 2009.

- ↑ Fredholm, Michael (1993). Burma: ethnicity and insurgency. Praeger. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-275-94370-7.

- 1 2 South, Ashley (2008). Ethnic politics in Burma: states of conflict. Taylor & Francis. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-203-89519-1.

- 1 2 Rotberg, Robert (1998). Burma: prospects for a democratic future. Brookings Institution Press. p. 169.

- ↑ Skidmore, Monique; Wilson, Trevor (2007). Myanmar: the state, community and the environment. ANU E Press. p. 69.

- 1 2 Shanty, Frank; Mishra, Patit Paban (2007). Organized crime: from trafficking to terrorism. ABC-CLIO. p. 70.

- ↑ A Failing Grade: Burma's Drug Eradication Efforts (PDF). Alternative ASEAN Network on Burma. 2004. ISBN 978-9749243343.

- ↑ Johnston, Tim (29 August 2009). "China Urges Burma to Bridle Ethnic Militia Uprising at Border". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Mullen, Jethro; Mobasherat, Mitra. "Myanmar says Kokang rebels killed 47 of its soldiers". CNN.

- ↑ Myanmar Kokang Rebels Deny Receiving Chinese Weapons

- ↑ "Deadly clashes hit Kokang in Myanmar's Shan state". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ↑ "Myanmar rebel clashes in Kokang leave 30 dead". BBC News. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.