Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar

| Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_(14763794285).jpg) | |||||

| Shah of Persia | |||||

| Reign | 1 May 1896 – 3 January 1907 | ||||

| Predecessor | Naser al-Din Shah Qajar | ||||

| Successor | Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar | ||||

| Prime Ministers |

See list

| ||||

| Born |

23 March 1853 Tehran, Persia | ||||

| Died |

3 January 1907 (aged 53) Tehran, Persia | ||||

| Burial | Imam Hussein Shrine, Kerbala, Iraq | ||||

| Spouse | Taj ol-Molouk | ||||

| Issue | See below | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Qajar | ||||

| Father | Naser al-Din Shah | ||||

| Mother | Shokuh-ol-Saltaneh | ||||

| Religion | Shia Islam | ||||

| Tughra |

| ||||

Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar, (Persian: مظفرالدین شاه قاجار, Mozaffar Ŝāh-e Qājār, Muẓaffari’d-Dīn Shāh Qājār; 23 March 1853 – 3 January 1907) was the fifth Qajar king of Persia (Iran), reigning from 1896 until his death in 1907.

He is credited with the creation of the Persian constitution, and often wrongly credited with the rise of the Persian Constitutional Revolution which took place immediately after his death.

Biography

The son of the Qajar ruler Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, Mozaffar ad-Din was named crown prince and sent as governor to the northern province of Azerbaijan in 1861. He spent his 35 years as crown prince in the pursuit of pleasure; his relations with his father were frequently strained, and he was not consulted in important matters of state. Thus, when he ascended the throne in May 1896, he was unprepared for the burdens of office.

At Mozaffar ad-Din's accession Persia faced a financial crisis, with annual governmental expenditures far in excess of revenues due to the policies of his father. During his reign, Mozzafar ad-Din attempted some reforms of the central treasury; however, the previous debt incurred by the Qajar court, owed to both England and Russia, significantly undermined this effort. He furthered this debt by borrowing even more funds from Britain, France, and Russia. The income from these later loans was used to pay earlier loans rather than create new economic developments. In 1908, oil was discovered in Persia but Mozzaffar ad-Din had already awarded William Knox D'Arcy, a British subject, the rights to oil in most of the country in 1901.[1]

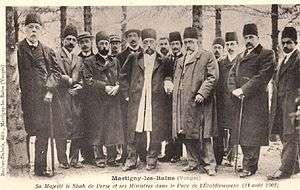

Like his father he visited Europe three times. During these periods, on the encouragements of his chancellor Amin-os-Soltan, he borrowed money from Nicholas II of Russia to pay for his extravagant traveling expenses. During his first visit he was introduced to the "cinematographe" in Paris, France. Immediately falling in love with the silver screen the Shah ordered his personal photographer to acquire all the equipment and knowledge needed to bring the moving picture to Persia, thus starting Persian cinema.[2] The following is a translated excerpt from the Shah's diary:

....[At] 9:00 P.M. we went to the Exposition and the Festival Hall where they were showing cinematographe, which consists of still and motion pictures. Then we went to Illusion building ....In this Hall they were showing cinematographe. They erected a very large screen in the centre of the Hall, turned off all electric lights and projected the picture of cinematography on that large screen. It was very interesting to watch. Among the pictures were Africans and Arabians traveling with camels in the African desert, which was very interesting. Other pictures were of the Exposition, the moving street, the Seine River and ships crossing the river, people swimming and playing in the water and many others that were all very interesting. We instructed Akkas Bashi to purchase all kinds of it [cinematographic equipment] and bring to Tehran so God willing he can make some there and show them to our servants.

Additionally, in order to manage the costs of the state and his extravagant personal lifestyle Mozzafar ad-din Shah decided to sign many concessions, providing foreigners with monopolistic control of various Persian industries and markets. One example being the D'Arcy Oil Concession.

Widespread fears amongst the aristocracy, educated elites, and religious leaders about the concessions and foreign control resulted in some protests in 1906. These resulted in the Shah accepting a suggestion to create a Majles (National Consultative Assembly) in October 1906, by which the monarch's power was curtailed as he granted a constitution and parliament to the people. He died of a heart attack 40 days after granting this constitution and was buried in Masumeh shrine in Qom.

Honours

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Leopold of Austria – 1893

- Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen – 1903

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle – 1893

- Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle – 29 May 1902 – during the visit to Berlin of the Shah[3]

_crowned.svg.png)

- Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation – May 1902 – during the visit to Rome of the Shah[4]

- Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus – 1903

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Order of St. Andrew – 1902

- Knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky – 1902

- Knight of the Order of the White Eagle – 1902

- Knight of the Order of Saint Stanislaus – 1902

- Knight of the Order of St. Anna, 1st Class in brilliants – 1902

.svg.png)

Children

Sons

- Prince Mohammad-Ali Mirza E’tezad es-Saltaneh, later Mohammad-Ali Shah (1872–1925)

- Prince Malek-Mansur Mirza Shoa os-Saltaneh (1880–1920)

- Prince Abolfath Mirza Salar od-Dowleh (1881–1961)

- Prince Abolfazl Mirza Azd os-Sultan (1882–1970)

- Prince Hossein-Ali Mirza Nosrat os-Saltaneh (1884–1945)

- Prince Nasser-od-Din Mirza Nasser os-Saltaneh (1897–1977)

Daughters

- Princess Fakhr os-Saltaneh (1870 – ?) married Abdol Majid Mirza Eyn od-Dowleh

- Princess Ehteram os-Saltaneh (1871 – ?) married Morteza-Qoli Khan Hedayat Sani od-Dowleh

- Princess Ezzat od-Dowleh (1872 – 1955) married Abdol Hossein Mirza Farmanfarma

- Princess Shokuh os-Saltaneh (1880 – ?)

- Princess Shokuh od-Dowleh (1883 – ?)

- Princess Fakhr-od-Dowleh (1883 – ?) mother of Ali Amini

- Princess Aghdas od-Dowleh (1891 – ?)

- Princess Anvar od-Dowleh (1896 – ?) married eghtedar es-Saltaneh son of Kamran Mirza

List of Premiers

- Mirza Ali-Asghar Khan Amin os-Soltan (till November 1896) (1st time)

- Post vacant (November 1896 – February 1897)

- Ali Khan Amin od-Dowleh (February 1897 – June 1898)

- Mirza Ali-Asghar Khan Amin os-Soltan (June 1898 – 24 January 1904) (2nd time)

- Prince Abdol-Majid Mirza Eyn od-Dowleh (24 January 1904 – 5 August 1906)

- Mirza Nasrollah Khan Ashtiani Moshir od-Dowleh (1906 – 18 February 1907)

Historical anecdotes

The Shah visited the United Kingdom in August 1902 on the promise of receiving the Order of the Garter as it had been previously given to his father, Nasser-ed-Din Shah. King Edward VII refused to give this high honor to a non-Christian. Lord Lansdowne, the Foreign Secretary, had designs drawn up for a new version of the Order, without the Cross of St. George. The King was so enraged by the sight of the design, though, that he threw it out of his yacht's porthole. However, in 1903, the King had to back down and the Shah was appointed a member of the Order.[7]

A nephew of his wife was Mohammed Mossadeq, the Prime Minister of Iran during the Pahlavi dynasty that was overthrown by a coup d'état staged by the United Kingdom and the United States in the 1950s.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar. |

- Qajar Dynasty

- Qajar family tree

- D'Arcy Concession

- Persian Constitutional Revolution

- Persian Constitution of 1906

- Anglo-Russian Entente

- Kamal ol-Molk

- Baghe Mozaffar, an Iranian TV show about a modern-day Qajar Khan

- Fakhr ol dowleh

- Samad Khan Momtaz os-Saltaneh, ambassador of Persia to Paris

References

- ↑ Cleveland, William L.; Bunton, Martin (2013). A history of the modern Middle East (Fifth edition. ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780813348339.

- ↑ Iranian Cinema: Before the Revolution<!— bot-generated title —> at www.horschamp.qc.ca

- ↑ "Latest intelligence - Germany". The Times (36781). London. 30 May 1902. p. 5.

- ↑ "Court Circular". The Times (36775). London. 23 May 1902. p. 7.

- ↑ "The Shah". The Times (36867). London. 8 September 1902. p. 4.

- ↑ Wm. A. Shaw, The Knights of England, Volume I (London, 1906) page 72

- ↑ Philip Magnus, King Edward the Seventh (London: John Murray, 1964) pages 301–5.

- Walker, Richard (1998). Savile Row: An Illustrated History

- The translation of the travelogue in Issari's book: Cinema in Iran: 1900–1979 pages 58–59

- Iranian Cinema: Before the Revolution at www.horschamp.qc.ca Iranian Cinema: Before the Revolution by Shahin Parhami.

- Hamid Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present, and Future, 320 p. (Verso, London, 2001), Chapter 1. ISBN 1-85984-332-8

External links

- Some fragmentary motion pictures of Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar: YouTube.

- Portrait of Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar: .

- Mohammad-Reza Tahmasbpoor, History of Iranian Photography: Early Photography in Iran, Iranian Artists' site, Kargah

- History of Iranian Photography. Postcards in Qajar Period, photographs provided by Bahman Jalali, Iranian Artists' site, Kargah.

- History of Iranian Photography. Women as Photography Model: Qajar Period, photographs provided by Bahman Jalali, Iranian Artists' site, Kargah.

- Photos of qajar kings

Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar Born: 1853 Died: 1907 | ||

| Iranian royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Naser al-Din Shah Qajar |

Shah of Persia 1896–1907 |

Succeeded by Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar |

_10_Toman.jpg)