Moshe Bejski

| Moshe Bejski | |

|---|---|

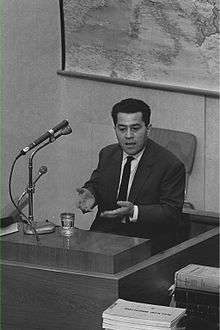

Bejski testifying at Adolf Eichmann's trial in Jerusalem, 1961 | |

| Born |

December 29, 1921 Działoszyce, Kielce Voivodeship, Poland |

| Died |

March 6, 2007 (aged 85) Tel Aviv, Israel |

| Occupation |

|

| Title | Judge of the Supreme Court of Israel |

| Term | 1979-1991 |

Moshe Bejski (29 December 1921 – 6 March 2007) was an Israeli Supreme Court Justice and President of Yad Vashem's Righteous Commission.

Biography

Childhood in Poland

Moshe Bejski was born in the village of Działoszyce, near Kraków, Poland, on December 29, 1920. During his youth, he joined a Zionist organization that organized the move of young Polish Jews to Palestine to build a new nation in the Jewish "promised land". However, he was not able to leave for Palestine with his before the invasion of Poland in 1939, he was not able to because of a health issues.[1]

The Holocaust

The German occupation of Kraków began September 6, 1939.[2] The area's Jews were murdered or required to live in the Kraków Ghetto. Bejski's parents and sister were shot soon after they were separated. In 1942, Bejski, along with his brothers Uri and Dov, ended up in the work camp[lower-alpha 1] of Płaszów.

Bejski felt an obligation to go back to the Płaszów camp, where he found his brothers again. He and his brothers eventually got placed on the famous list for Oskar Schindler's factory in Czechoslovakia, where they spent the remainder of the war in relative safety. They were liberated by the Red Army in May 1945. When the brothers discovered the fate of their parents and sister, they decided to emigrate to Palestine.

New life in Israel

Beski was able to begin a new life in the place of his dreams that he hadn't been able to reach when he was a boy, but his Zionist dream soon clashed with the reality. His brother Uri was killed by an Arab sniper on the day the Jewish State was recognized by the UN. He served in the Israel Defense Forces during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, reaching the rank of Captain. In 1949, he was sent to France to manage the Youth Aliyah department in Europe and North Africa until 1952. Although originally dreamed of having been an engineer, Bejski studied law at the Sorbonne, and was awarded a doctorate in law for a thesis on human rights in the Bible. After returning to Israel, he was certified as a lawyer in 1953 and became one of the most reputable lawyers in Tel Aviv. He was appointed a magistrate judge in 1960, a district judge from 1968 to 1979, and a judge on the Supreme Court of Israel until 1991.

The Eichmann Trial

Moshe Bejski left his past in German-occupied Poland behind him. For years no one knew of his tragic history; he was thought to be Zionist who came to Palestine before the Nazi persecution or even a native born Israeli. He only willingly revealed his story and origins in 1961, during the trial against Adolf Eichmann. He was called on by Prosecutor Gideon Hausner to testify about the Płaszów concentration camp. Bejski delivered an emotional account of the circumstances at the camp and he conveyed the tragic despair and helplessness of its inmates to the court.

For the first time in Israel, the deep unease of the European refugees who survived to the Shoah (Holocaust) was revealed. There were those who were unable to integrate themselves and be accepted by a populace who despised them and accused them of cowardice and lack of rebellion against the Nazis. A huge debate opened around the world, also stirred by the polemic contribution of Hannah Arendt, a German philosopher of Jewish descent who escaped to America in the 1930s. The hardships connected to the history of the Jews during World War II was divulged.

President of the Righteous Commission

The Yad Vashem Memorial was established in Jerusalem for eternal remembrance and acknowledgment of the Holocaust victims. In 1953, the State of Israel committed itself to bestowing an honor to the non-Jews who had saved Jewish lives; they were awarded with the highest title, that of Righteous among the Nations.

The Righteous Commission was established and given the task of running investigations to discover the acts of rescue and to find who the title must be awarded to. The most well-known judge in Israel at the time, Moshe Landau, who had presided over the Eichmann trial and issued the death verdict, was appointed president. Landau soon left the position and proposed that the nomination be given to Bejski. Bejski replaced him in 1970 and kept the presidency until 1995, when he retired. In that time nearly eighteen thousand Righteous had been honored and had been able to plant a tree in the avenue dedicated to remembering them and their gestures at Yad Vashem.

Moshe Bejski's role in the activity of the Righteous Commission was crucial. At the risk of clashing with Landau's views, he wanted to award not only the small number of significant cases, but also all who expressed the intention to rescue a persecuted Jew, those who hadn't succeeded in saving them, and those who had rescued without risking their lives. As the new President of the Commission he decided that it wasn't necessary to have behaved like a hero to obtain the honor. The great number of cases reported to Yad Vashem proves that there had been a real involvement of many people, common people, in the attempt to wrench the Jews from extermination. Making the stories of the righteous known meant debunking the myth that opposition against Nazism was an impossible deed and that there wasn't any possibility of helping the persecuted without running extreme risks. Many times a little intervention was all that was needed to prevent a big tragedy. This is why it is important to value and publicly feature every gesture that was made in favor of the Jews in Nazi occupied Europe. To obtain results Bejski dedicated everything he had to the cause. He dedicated the best years of his life to it. He gave up much of his private life and remained late at work to run the meetings of the Commission after the intense days at the Constitutional Court. His commitment spread enthusiasm to the other members and raised competence. He created subdivisions that were able to deal with more cases and investigate every last useful element for a correct and authentic evaluation.

The dilemmas he found himself confronted with were enormous. How do you judge he who has saved a Jew, but killed another man after the war? What about the woman who hid the persecuted while she prostituted herself for the Nazi officials? Or those who saved dozens of Jews in Poland but remained steadfast in their anti-Semitic opinions? What about those who helped but only for a price?

There was also the idea of individual moral debt of the survivor that stemmed from thankfulness to their saviors. This moral debt led Bejski to become personally involved with his own rescuer, Oskar Schindler. After finding him again at the beginning of the 1960s and wrenching him out of bankruptcy and imprisonment in Germany, he invited him to Israel where he valiantly committed to honoring Schindler's actions. Because of Bejski's commitment to him, Spielberg was able to create him film, which made him famous across the world. Bejski committed to helping other Righteous people besides Schindler. He fought hard to obtain the Israeli state's commitment to help those who lived precariously in the Eastern European Countries or those who needed medical assistance.

Bejski Commission

In the aftermath of the 1983 Israel bank stock crisis, the Bejski Commission was formed, with Moshe Bejski as chairman.

Death

Bejski died in Tel Aviv, Israel, on March 6, 2007, at age 85.

Legacy

Bejksi is referred to several times in the book Night by Elie Wiesel and was asked to write a response to the philosophical question posed in The Sunflower by Simon Wiesenthal.

Notes

- ↑ Płaszów would later be converted from a labor camp to an official concentration camp.

References

- ↑ "Moshe Bejski". en.gariwo.net. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ↑ "Kraków, Poland Jewish History Tour". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

Further reading

- Gabriele Nissim, "Il Tribunale del Bene", Milan, Mondadori, 2003. ISBN 88-04-48966-9 (This, with its translations into a number of languages, is the only existing book about Moshe Bejski.)

External links

- Bejski page in the Garden of the righteous Worldwide Committee

- Yad Vashem – The Righteous Among the Nations

- Oral history interview with Moshe Bejski