Mordred

| Mordred | |

|---|---|

| Matter of Britain character | |

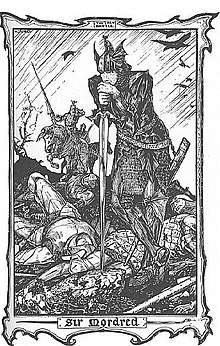

Sir Mordred by H. J. Ford (1902) | |

| First appearance | Historia Regum Britanniae |

| Created by | Geoffrey of Monmouth |

| Information | |

| Occupation | Knight of the Round Table, usurper king |

| Title | Sir, King |

| Spouse(s) | Guinevere or others |

| Children | Two sons including Melehan |

| Relatives | Arthur/Lot, Morgause, Gawain, Agravain, Gaheris, Gareth |

| Nationality | Briton |

Mordred or Modred (/ˈmoʊdrɛd/; Welsh: Medrawt) is a character in the Arthurian legend. He is most commonly known as a notorious traitor who fought King Arthur at the Battle of Camlann, where he was killed and Arthur was fatally wounded.

Name

The name Mordred (found as Modredus in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae) comes from Old Welsh Medraut (comparable to Old Cornish Modred and Old Breton Modrot) and is ultimately derived from Latin Moderātus meaning "within bounds, observing moderation, moderate".[1][2]

Early depictions

The earliest surviving mention of Mordred (referred to as Medraut) occurs in the Annales Cambriae entry for the year 537, which references his name in association with the Battle of Camlann.[3]

Gueith Camlann in qua Arthur et Medraut corruerunt.

"The strife of Camlann, in which Arthur and Medraut fell."

This brief entry gives no information as to whether Mordred killed or was killed by Arthur, or even if he was fighting against him. As Leslie Alcock has noted, the reader assumes this in the light of later tradition.[4]

The Annales themselves were completed between 960 and 970, meaning that although their authors likely drew from older material[5] they cannot be considered as a contemporary source having been compiled 400 years after the events they describe.[6]

Meilyr Brydydd, writing at the same time as Geoffrey of Monmouth, mentions Mordred in his lament for the death of Gruffudd ap Cyan (d. 1137). He describes Gruffudd as having eissor Medrawd ("the nature of Medrawd") as to have valour in battle. Similarly, Gwalchmai ap Meilyr praised Madog ap Maredudd, king of Powys (d. 1160) as having Arthur gerdernyd, menwyd Medrawd ("Arthur's strength, the good nature of Medrawd").[7] This would support the idea that early perceptions of Mordred were largely positive.

Later depictions

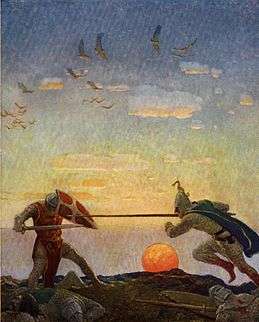

"Then the king ran towards Sir Mordred, crying, 'Traitor, now is thy death day come.'"

Mordred (referred to as Modredus) is found in Geoffrey's Historia, written around 1136; here, he is portrayed as the nephew of and traitor to Arthur. The account describes Arthur leaving Mordred in charge of his throne as he crossed the English Channel to wage war on Lucius Tiberius of Rome. During Arthur's absence, Mordred crowns himself king and lives in an adulterous union with Arthur's wife, Guinevere. Geoffrey does not make it clear how complicit Guinevere is with Mordred's actions, simply stating that the Queen had "broken her vows" and "about this matter... [he] prefers to say nothing."[8] This forces Arthur to return to Britain to fight at the Battle of Camlann, where Mordred is ultimately slain. Arthur, having been mortally wounded in battle, is sent to Avalon.

A number of Welsh sources also refer to Medraut, usually in relation to Camlann. One triad, based on Geoffrey's Historia, provides an account of his betrayal of Arthur;[9] in another, he is described as the author of one of the "Three Unrestrained Ravagings of the Isle of Britain" – he came to Arthur's court at Kelliwic in Cornwall, devoured all of the food and drink, and even dragged Gwenhwyfar (Guinevere) from her throne and beat her.[10]

Family

Tradition varies on his relationship to Arthur, but he is best known today as Arthur's illegitimate son by his half-sister Morgause, though in many modern adaptations she is merged with the character of Morgan le Fay. In earlier literature, he was considered the legitimate son of Morgause, also known as Anna, with her husband King Lot of Orkney. His brothers or half-brothers are Gawain, Agravain, Gaheris, and Gareth.

Medraut is never considered Arthur's son in Welsh texts, only his nephew, though The Dream of Rhonabwy mentions that the king had been his foster father. However, Mordred's later characterization as the king's villainous son has a precedent in the figure of Amhar (or Amr), a son of Arthur's known from only two references. The more important of these, found in an appendix to the Historia Britonum, describes his marvellous grave beside the Herefordshire spring where he had been slain by his own father in some unchronicled tragedy.[11][12] What connection exists between the stories of Amr and Mordred, if there is one, has never been satisfactorily explained.

The 14th-century Scottish chronicler John of Fordun even claimed that Mordred was the rightful heir to the throne of Britain, as Arthur was an illegitimate child (in his account, Mordred was the legitimate son of Lot and Anna, who here is Uther's sister). This sentiment was elaborated upon by Walter Bower and by Hector Boece, who in his Historia Gentis Scotorum goes so far as to say Arthur and Gawain were traitors and villains who stole the throne from Mordred. According to Boece, Arthur agreed to make Mordred his heir but then, on the advice of the Britons who did not want Mordred to rule, he made Constantine his heir. This led to the war in which Arthur and Mordred die.

In Geoffrey and certain other sources such as the Alliterative Morte Arthure, Mordred marries Guinevere, seemingly consensually, after he steals the throne. However, in later writings like the Lancelot-Grail Cycle and Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, Guinevere is not treated as a traitor and she flees Mordred's proposal and hides in the Tower of London. Adultery is still tied to her role in these later romances, however, but Mordred has been replaced with Lancelot.

The 18th-century Welsh antiquarian Lewis Morris, based on statements made by the Scottish chronicler Hector Boece, suggested that Medrawd had a wife named Cwyllog (also spelled Cywyllog), daughter of Caw.[13] Another late Welsh tradition was that Medrawd's wife was Gwenhwy(f)ach, sister of Gwenhwyfar.[13]

Offspring

Geoffrey and the Lancelot-Grail Cycle have Mordred being succeeded by his sons. Stories always number them as two, though they are usually not named, nor is their mother.

In Geoffrey's version, after the Battle of Camlann, Constantine is appointed Arthur's successor. However, Mordred's two sons and their Saxon allies rise against him.[14] After defeating them, one of them flees to sanctuary in the Church of Amphibalus in Winchester while the other hides in a London friary.[15] Constantine tracks them down, and kills them before the altars in their respective hiding places.[15] This act invokes the vengeance of God, and three years later Constantine is killed by his nephew Aurelius Conanus.[15] Geoffrey's account of the episode may be based on Constantine's murder of two "royal youths" as mentioned by the 6th-century writer Gildas.[16]

The elder of Mordred's sons is named Melehan or some derivation in the Lancelot-Grail and Post-Vulgate Cycles. In these texts, Lancelot and his men return to Britain to dispatch Melehan and his brother after receiving a letter from the dying Gawain. In the ensuing battle Melehan slays Sir Lionel, son of King Bors the Elder and brother to Sir Bors the Younger. Bors kills Melehan, avenging his brother's death, while Lancelot kills the unnamed younger brother.

In later works

Virtually everywhere Mordred appears, his name is synonymous with treason. He appears in Dante's Inferno in the lowest circle of Hell, set apart for traitors: "him who, at one blow, had chest and shadow / shattered by Arthur's hand" (Canto XXXII).[17] Mordred is especially prominent in popular modern era Arthurian literature, as well as in film, television, and comics.[18]

A few works of the Middle Ages and today, however, portray Mordred as less a traitor and more a conflicted opportunist, or even a victim of fate. Even Malory, who depicts Mordred as a villain, notes that the people rallied to him because, "with Arthur was none other life but war and strife, and with Sir Mordred was great joy and bliss."

See also

References

- ↑ Cane, Meredith. Personal Names of Men in Wales, Cornwall and Brittany 400-1400 AD, University of Wales Ph.D. thesis, 2003, pp. 273-4.

- ↑ Lewis, Charlton, T., An Elementary Latin Dictionary, New York, Cincinnati, and Chicago. American Book Company. 1890.

- ↑ Lupack, Alan (translator). "Arthurian References in the 'Annales Cambriae'. Camelot Project at the University of Rochester. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- ↑ Leslie Alcock, Arthur's Britain: History and Archaeology A.D. 367-634, London, Penguin Books, 2001, p. 88.

- ↑ Ashe, Geoffrey (1991). "Annales Cambriae". In Lacy, Norris J. (Ed.), The New Arthurian Encyclopedia, pp. 8–9. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-4377-4.

- ↑ Thomas Green, Concepts of Arthur, Chalford, Tempus Publishing, 2007, p. 27

- ↑ O J Padel, Arthur in Medieval Welsh Literature, Cardiff, University of Wales Press, 2013, Google Book. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ↑ Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain, XI.I.

- ↑ Triad 51. In Bromwich, Rachel (2006). Trioedd Ynys Prydein.

- ↑ Triad 54. In Bromwich, Rachel (2006). Trioedd Ynys Prydein.

- ↑ Nennius, Historia Brittonum, ch. 73. From Lupack, Alan (translator). "From the 'History of the Britons' ('Historia Brittonum') by Nennius. The Camelot Project at the University of Rochester. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- ↑ The Arthurian Handbook, p. 15; p. 277.

- 1 2 Bartrum, Peter, A Welsh Classical Dictionary, National Library of Wales, 1993, p. 180.

- ↑ Historia Regum Britanniae, Book 11, ch. 3.

- 1 2 3 Historia Regum Britanniae, Book 11, ch. 4.

- ↑ De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, ch. 28–29.

- ↑ Inferno, Canto XXXII, lines 61–62, Mandelbaum translation.

- ↑ Torregrossa, Michael A., "Will the 'Reel' Mordred Please Stand Up? Strategies for Representing Mordred in American and British Arthurian Film" in Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays (Rev. edn.), ed. Kevin J. Harty. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002 (pb. 2009), pp. 199–210.

Sources

- Alcock, Leslie (1971). Arthur's Britain, p. 88. London: Penguin Press.

- Bromwich, Rachel (2006). Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain. University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-1386-8

- Lacy, Norris J. (Ed.), The New Arthurian Encyclopedia, pp. 8–9. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-4377-4.

- Lacy, Norris J.; Ashe, Geoffrey; and Mancroff, Debra N. (1997). The Arthurian Handbook. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8153-2081-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mordred. |

- Mordred at The Camelot Project

- Several accounts of Mordred's death