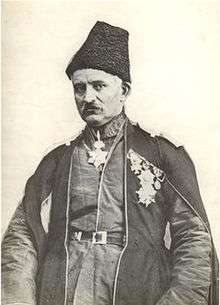

Mirza Fatali Akhundov

| Mirza Fatali Akhundzade | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

12 July 1812 Nukha, Shaki Khanate, Qajar dynasty |

| Died |

9 March 1878 (aged 65) Tiflis, Tiflis Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Occupation | Playwright, philosopher |

Mirza Fatali Akhundzade (Azerbaijani: Mirzə Fətəli Axundov میرزا فتحعلی آخوندزاده) or Mirza Fath-Ali Akhundzade, also known as Akhundov (12 July 1812 – 9 March 1878), was a celebrated Iranian ethnic Azerbaijani[1] author, playwright, philosopher, and founder of modern literary criticism,[2] "who acquired fame primarily as the writer of European-inspired plays in the Azeri Turkic language".[3] Akhundzade singlehandedly opened a new stage of development of Azerbaijani literature. He was also the founder of materialism and atheism movement in Azerbaijan[4] and one of forerunners of modern Iranian nationalism.[5]

Life

Akhundzade was born in 1812 in Nukha (present-day Shaki, Azerbaijan) to a wealthy land owning family from Iranian Azerbaijan. His parents, and especially his uncle Haji Alaskar, who was Fatali's first teacher, prepared young Fatali for a career in Shi'a clergy, but the young man was attracted to the literature. In 1832, while in Ganja, Akhundzade came into contact with the poet Mirza Shafi Vazeh, who introduced him to a Western secular thought and discouraged him from pursuing a religious career.[6] Later in 1834 Akhundzade moved to Tiflis (present-day Tbilisi, Georgia), and spent the rest of his life working as a translator of Oriental languages in the service of the Russian Empire's Viceroyalty. Concurrently, from 1837 onwards he worked as a teacher in Tbilisi uezd Armenian school, then in Nersisyan school. In Tiflis his acquaintance and friendship with the exiled Russian Decembrists Alexander Bestuzhev-Marlinsky, Vladimir Odoyevsky, poet Yakov Polonsky, Armenian writers Khachatur Abovian, Gabriel Sundukyan and others played some part in formation of Akhundzade's Europeanized outlook.

Akhundzade's first published work was The Oriental Poem (1837), written to lament the death of the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. But the rise of Akhundzade's literary activity comes in the 1850s. In the first half of the 1850s, Akhundzade wrote six comedies – the first comedies in Azerbaijani literature as well as the first samples of the national dramaturgy. The comedies by Akhundzade are unique in their critical pathos, analysis of the realities in Azerbaijan of the first half of the 19th century. These comedies found numerous responses in the Russian other foreign periodical press. The German Magazine of Foreign Literature called Akhundzade "dramatic genius", "the Azerbaijani Molière" 1. Akhundzade's sharp pen was directed against everything that he believed hindered the advance of the Russian Empire, which for Akhundzadeh was a force for modernisation, in spite of the atrocities it committed in its southern advance against Akhundzadeh's own kin.[7] According to Walter Kolarz:

The greatest Azerbaidzhani poet of the nineteenth century, Mirza Fathali Akhundov (1812-78), who is called the "Molière of the Orient", was so completely devoted to the Russian cause that he urged his compatriots to fight Turkey during the Crimean War.[8]

In 1859 Akhundzade published his short but famous novel The Deceived Stars. In this novel he laid the foundation of Azerbaijani realistic historical prose, giving the models of a new genre in Azerbaijani literature. By his comedies and dramas Akhundzade established realism as the leading trend in Azerbaijani literature.

According to Ronald Grigor Suny:

Turkish nationalism, which developed in part as a reaction to the nationalism of the Christian minorities [of the Ottoman Empire], was, like Armenian nationalism, heavily influenced by thinkers who lived and were educated in the Russian Empire. The Crimean Tatar Ismail Bey Gasprinski and the Azerbaijani writer Mirza Fath Ali Akhundzade inspired Turkish intellectuals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[9]

According to Tadeusz Swietochowski:

In his glorification of the pre-Islamic greatness of Iran, before it was destroyed at the hands of the "hungry, naked and savage Arabs, "Akhundzada was one of the forerunners of modern Iranian nationalism, and of its militant manifestations at that. Nor was he devoid of anti-Ottoman sentiments, and in his spirit of the age-long Iranian Ottoman confrontation he ventured into his writing on the victory of Shah Abbas I over the Turks at Baghdad. Akhundzade is counted as one of the founders of modern Iranian literature, and his formative influence is visible in such major Persian-language writers as Malkum Khan, Mirza Agha Khan and Mirza Abd ul-Rahim Talibov Tabrizi. All of them were advocates of reforms in Iran. If Akhundzade had no doubt that his spiritual homeland was Iran, Azerbaijan was the land he grew up and whose language was his native tongue. His lyrical poetry was written in Persian, but his work that carry messages of social importance as written in the language of the people of his native land, azari. With no indication of split-personality, he combined larger Iranian identity with Azerbaijani – he used the term vatan (fatherland) in reference to both.[5]

Reza Zia-Ebrahimi too considers Akhundzade as the founding-father of what he calls 'dislocative nationalism' in Iran. According to Zia-Ebrahimi, Akhundzade found inspiration in Orientalist templates to construct a vision of ancient Iran, which offered intellectuals disgruntled with the pace of modernist reform in Iran, a self-serving narrative where all of Iran's shortcomings are blamed on a monolithic and otherized 'other': the Arab. For Zia-Ebrahimi, Akhundzade must be credit with the introduction of ethno-racial ideas, particularly the opposition between the Iranian Aryan and the Arab Semite, into Iran's intellectual debates. Zia-Ebrahimi disputes that Akhundzade had any influence on modernist intellectuals such as Malkum Khan (beyond a common project to reform the Alphabet used to write Persian) or Talibov Tabrizi. His real heir was Kermani, and these two intellectuals' legacy is to be found in the ethnic nationalism of the Pahlavi state, rather than the civic nationalism of the Constitutional movement.[10]

In the 1920s, the Azerbaijan State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre was named after Akhundzade.

Iranian nationalism

Akhundzade identified himself as belonging to the nation of Iran (mellat-e Irān) and to the Iranian homeland (waṭan). He corresponded with Jālāl-al-Din Mirzā (a minor Qajar prince, son of Bahman Mirza Qajar,1826–70) and admired this latter's epic Nāmeh-ye Khosrovān ('Book of Sovereigns'), which was an attempt to offer the modern reader a biography of Iran's ancient kings, real and mythical, without recourse to any Arabic loanword. The Nāmeh presented the pre-Islamic past as one of grandeur, and the advent of Islam as a radical rupture.[11]

For Zia-Ebrahimi, Akhundzade is the founder of what he refers to as 'dislocative nationalism'. Zia-Ebrahimi defines dislocative nationalism as

'an operation that takes place in the realm of the imagination, an operation whereby the Iranian nation is dislodged from its empirical reality as a majority-Muslim society situated - broadly - in the "East". Iran is presented as an Aryan nation adrift, by accident, as it were, from the rest of its fellow Aryans (read: Europeans).'[12]

Dislocative nationalism is thus predicated on more than a total distinction between supposedly Aryan Iranians and Semitic Arabs, as it is suggested that the two races are incompatible and in opposition to each other. These ideas are directly indebted to nineteenth-century racial thought, particularly the Aryan race hypothesis developed by European comparative philologists (a hypothesis that Zia-Ebrahimi discusses at length [13]). Dislocative nationalism presents the pre-Islamic past as the site of a timeless Iranian essence, dismisses the Islamic period as one of decay, and blames all of Iran's shortcomings in the nineteenth and later twentieth century on Arabs and the adoption of Islam. The advent of Islam is thus ethnicised into an 'Arab invasion' and perceived as a case of racial contamination or miscegenation. According to Zia-Ebrahimi, dislocative nationalism does not, in itself, offer a blueprint for reforming the state beyond calls to eliminate what it arbitrarily defines as the legacy of Arabs: Islam and Arabic loanwords.

Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani (1854–96) was one of Akhundzades disciples, and three decades later will endeavour to disseminate Akhundzade's thought while also significantly strengthening its racial content (Zia-Ebrahimi argues that Kermani was the first to retrieve the idea of 'the Aryan race' from European texts and refer to it as such, the modern idea of race here being different to the various cognates of the term 'Ariya' that one finds in ancient sources). Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani also followed Jalāl-al-Din Mirzā in producing a national history of Iran, Āʾine-ye sekandari (The Alexandrian Mirror), extending from the mythological past to the Qajar era, again to contrast a mythified and fantasised pre-Islamic past with a present that falls short of nationalist expectations.[14]

Zia-Ebrahimi sees dislocative nationalism as the dominant paradigm of identity in modern Iran, as it became part and parcel of the official ideology of the Pahlavi State (1925–79) and thus disseminated through mass-schooling, propaganda, and the state's symbolic repertoire.

Alphabet Reform

Well ahead of his time, Akhundzade was a keen advocate for alphabet reform, recognizing deficiencies of Perso-Arabic script with regards to Turkic sounds. He began his work regarding alphabet reform in 1850. His first efforts focused on modifying the Perso-Arabic script so that it would more adequately satisfy the phonetic requirements of the Azerbaijani language. First, he insisted that each sound be represented by a separate symbol - no duplications or omissions. The Perso-Arabic script expresses only three vowel sounds, whereas Azeri needs to identify nine vowels. Later, he openly advocated the change from Perso-Arabic to a modified Latin alphabet. The Latin script which was used in Azerbaijan between 1922 and 1939, and the Latin script which is used now, were based on Akhundzade's third version.

Legacy

Beside of his role in Azerbaijani literature and Iranian nationalism, Akhundzadeh was also known for his harsh criticisms of religions (mainly Islam) and stays as the most iconic Azerbaijani atheist.[15] National Library of Azerbaijan and Azerbaijan State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre as well as couple of streets, parks and libraries are also named after Akhundzade in Azerbaijan. A cultural museum in Tbilisi, Georgia that focuses on Georgian-Azerbaijani cultural relations is also named after him.

Punik, town in Armenia was also named in the honour of Akhundzade until very recently. TURKSOY hosted a groundbreaking ceremony to declare 2012 as year of Mirza Fatali Akhundzade.

Bibliography

He published many works on literary criticism:

- Qirītīkah ("Criticism")

- Risālah-i īrād ("Fault-finding treatise")

- Fann-i kirītīkah ("Art of criticism")

- Darbārah-i Mullā-yi Rūmī va tasnīf-i ū ("On Rumi and his work")

- Darbārah-i nazm va nasr ("On verse and prose")

- Fihrist-i kitāb ("Preface to the book")

- Maktūb bih Mīrzā Āqā Tabrīzī ("Letter to Mīrzā Āqā Tabrīzī")

- Uṣūl-i nigārish ("Principles of writing")

References

- ↑ ĀḴŪNDZĀDA ĀḴŪNDZĀDA (in Soviet usage, AKHUNDOV), MĪRZĀ FATḤ-ʿALĪ (1812-78), Azerbaijani playwright and propagator of alphabet reform; also, one of the earliest and most outspoken atheists to appear in the Islamic world. According to his own autobiographical account (first published in Kaškūl, Baku, 1887, nos. 43-45, and reprinted in M. F. Akhundov, Alefbā-ye ǰadīd va maktūbāt, ed. H. Moḥammadzāda and Ḥ. Ārāslī, Baku, 1963, pp. 349-55), Āḵūndzāda was born in 1812 (other documents give 1811 and 1814) in the town of Nūḵa, in the part of Azerbaijan that was annexed by Russia in 1828. His father, Mīrzā Moḥammad-Taqī, had been kadḵodā of Ḵāmena, a small town about fifty kilometers to the west of Tabrīz, but he later turned to trade and, crossing the Aras river, settled in Nūḵa, where in 1811 he took a second wife. One year later, she gave birth to Mīrzā Fatḥ-ʿAlī. Āḵūndzāda’s mother was descended from an African who had been in the service of Nāder Shah, and consciousness of this African element in his ancestry served to give Āḵūndzāda a feeling of affinity with his great Russian contemporary, Pushkin.

- ↑ Parsinejad, Iraj. A History of Literary Criticism in Iran (1866-1951). He lived in the Russian Empire. Bethesda, MD: Ibex, 2003. p. 44.

- ↑ Millar, James R. Encyclopedia of Russian History. MacMillan Reference USA. p. 23. ISBN 0-02-865694-6.

- ↑ M. Iovchuk (ed.) et el. [The Philosophical and Sociological Thought of the Peoples of the USSR in the 19th Century http://www.biografia.ru/about/filosofia46.html]. Moscow: Mysl, 1971.

- 1 2 Tadeusz Swietochowski, Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition (New York: Columbia University Press), 1995, page 27-28:

- ↑ Shissler, A. Holly (2003). Between Two Empires: Ahmet Agaoglu and the New Turkey. I.B. Tauris. p. 104. ISBN 1-86064-855-X.

- ↑ Zia-Ebrahimi, Reza (2016). The emergence of Iranian nationalism: Race and the politics of dislocation. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 141–45. ISBN 9780231541114.

- ↑ Kolarz W. Russian and Her Colonies. London. 1953. pp 244-245

- ↑ Ronald Grigor Suny Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana State University, 1993. page 25

- ↑ Zia-Ebrahimi, Reza (2016). The emergence of Iranian nationalism: Race and the politics of dislocation. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Zia-Ebrahimi, Reza (2016). The emergence of Iranian nationalism: Race and the politics of dislocation. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Zia-Ebrahimi, Reza (2016). The emergence of Iranian nationalism: Race and the politics of dislocation. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 5.

- ↑ Zia-Ebrahimi, Reza (2011). "Self-Orientalization and dislocation: The uses and abuses of the "Aryan discourse" in Iran". Iranian Studies. 44 (4).

- ↑ Ashraf, AHMAD. "IRANIAN IDENTITY iv. 19TH-20TH CENTURIES". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ Ахундов М. Ф. - Великие люди - Атеисты

External links

- Biography.

- Akhundov: Alphabet Reformer Before His Time, Azerbaijan International, Vol 8:1 (Spring 2000).

- http://mirslovarei.com/content_fil/AXUNDOV-MIRZA-FATALI-2072.html

- Rebecca Ruth Gould, “The Critique of Religion as Political Critique: Mīrzā Fatḥ ʿAlī Ākhūndzāda’s Pre-Islamic Xenology,” Intellectual History Review 26.2 (2016): 171-184.