Miladinov brothers

.pdf.jpg)

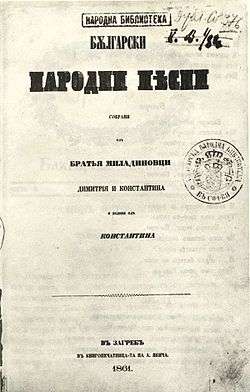

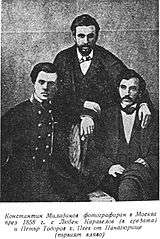

The Miladinov brothers (Bulgarian: Братя Миладинови, Bratya Miladinovi, Macedonian: Браќа Миладиновци, Brakja Miladinovci), Dimitar Miladinov (1810–1862) and Konstantin Miladinov (1830–1862), were Bulgarian poets and folklorists from the region of Macedonia, authors of an important collection of folk songs, Bulgarian Folk Songs.[4][5] In their writings, they self identified as Bulgarians,[6][7] though besides contributing to Bulgarian literature,[8] in the Republic of Macedonia they are also thought to have laid the foundation of the Macedonian literary tradition.[9]

The collection Bulgarian Folk Songs includes a total of 665 songs and 23,559 verses. Another famous poem by Konstantin Miladinov is Taga za Yug (Тъга за юг), that he wrote during his stay in Russia. Their hometown hosts the international Struga Poetry Evenings festival in their honour including a poetry award named after them. Miladinov brothers collection marked the beginning of the Bulgarian folklore studies in the period of the Bulgarian National Revival with the richness and variety of collected folk songs.[10]

Dimitar Miladinov

Dimitar Miladinov was born in Struga, Ottoman Empire (in what is now the Republic of Macedonia) in 1810. His mother was Sultana and father Hristo Miladinov. With the assistance from friends, Dimitar was sent to [[Ioannina, at that time, a prominent Greek educational center. He had absorbed much of the Greek culture including their classics, and became proficient in the Greek language. In 1829, he stayed in the Saint Naum monastery in Ohrid to continue his education, and in 1830 he became a teacher in Ohrid. Meanwhile, his father died, and his brother was born - Konstantin Miladinov. The Miladinov family had eight children — six boys and two girls: Dimitar (the oldest), Atanas, Mate, Apostol, Naum, Konstantin, Ana and Krsta. In 1832, he moved to Durrës, Albania, working in the local trade chamber. From 1833 through 1836 he studied in Ioannina, preparing to become teacher. Eventually he returned to Ohrid and began teaching.

In 1836, he introduced a new teaching method in his classroom.[11] He increased the school programme with new subjects, such as philosophy, arithmetics, geography, Old Greek and Greek literature, Latin and French. Soon he became popular and respected among his students and peers. After two years, he left Ohrid and returned to Struga. From 1840 to 1842, he was a teacher in Kukush, today in Greece. He became active in the town's social life, strongly opposing the phanariotes. At the instigation of Dimitar Miladinov, and with the full approval of the city fathers, in 1858, the use of the Greek language was banished from the churches and substituted with the Old Bulgarian. In 1859 he received word that Ohrid had officially demanded, from the Turkish government, the restoration of Bulgarian Patriarchate. Dimitar Miladinov left Kukush and headed for Ohrid to help. There he translated Bible texts in the Bulgarian language (considered in the Republic of Macedonia as Macedonian). Dimitar Miladinov tried to introduce the Bulgarian language into the Greek school in Prilep in 1856 causing an angry reaction from the local Grekomans. In a letter to "Tsarigradski Vestnik" of February 28, 1860, he reports: "…In the entire country of Ohrid, there is not a single Greek family, except three or four villages of Vlahs. All of the rest of the population is pure Bulgarian.…"[12] Angered by this act of the citizens of Ohrid and their leader, the Greek Bishop Miletos denounced Miladinov as a Russian agent. He was accused of spreading pan-Slavic ideas and was imprisoned in Istanbul later to be joined by his supporting brother Konstantin. In January 1862 both brothers died in prison from typhus.[13]

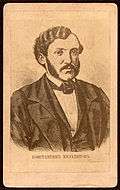

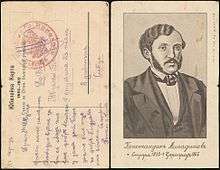

Konstantin Miladinov

Konstantin Miladinov was the youngest son in the family of the potter Hristo Miladinov. He was born in 1830 in Struga. He studied in a few different places throughout his life but the very first teacher was his older brother Dimitar. After his graduation from the Greek institute at Ioannina and the University of Athens, where he studied literature, at the instigation of his brother, Dimitar, and following the example of many young Bulgarians of that period, in 1856, Konstantin went to Russia. Reaching Odessa, and short of money, the Bulgarian Society in that city financed his trip to Moscow. Konstantin enrolled at the Moscow University to study Slavic philology. While at the University of Athens, he was exposed, exclusively, to the teachings and thinking of ancient and modern Greek scholars. In Moscow, he came in contact with prominent Slavic writers and intellectuals, scarcely mentioned in any of the Greek textbooks. But while in Moscow he could not suppress his desire to see the River Volga. At the time of his youth, the universal belief was that the Bulgars had camped on the banks of the legendary river, had crossed it on their way to the Balkans and the origin of the name Bulgarians had come from the Russian River - Volga. Reaching its shores, Konstantin stood before it in awe, fascinated, unable to utter a word, his eyes following the flowing waters. A poet at heart, he poured his exaltations in a letter to one of his friends: "…O,Volga, Volga! What memories you awake in me, how you drive me to bury myself in the past! High are your waters, Volga. I and my friend, also a Bulgarian, we dived and proudly told ourselves that, at this very moment, we received our true baptismal.…"[14] While in Russia he helped his older brother Dimitar in editing the materials for the collection of Bulgarian songs, that have been collected by Dimitar in his field work. The collection was subsequently published in Croatia with the support of the bishop Josip Strosmayer, who was one of the patrons of Slavonic literature at that time. Konstantin established contact with Josip Juraj Strossmayer and early in 1860, when he heard that the Bishop would be in Vienna, he left Moscow and headed for the Austrian capital to meet his future benefactor. Very glad that he printed the book, on the way back he received the bad news that his brother was jailed. With the thought of helping his brother he went in Tsarigrad. Denounced by the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople as a dangerous Russian agent, he was arrested. It is not clear whether he was placed in the same cell with his brother, or whether the two brothers saw each other. Very soon both of them became ill and in matter of few days died.

Significance

The two brothers' educationalist activity and deaths ensured them a worthy place in the history of the Bulgarian cultural movement and the Bulgarian national liberation struggle in the 19th century. The brothers are known also for their keen interest in Bulgarian folk poetry as a result of which the collection "Bulgarian Folk Songs" appeared. The songs were collected between 1854 and 1860 mostly by the elder brother, Dimitar, who taught in several Macedonian towns (Ohrid, Struga, Prilep, Kukush and Bitola) and was able to put into writing the greater part of the 660 folk songs. The songs from the Sofia District were supplied by the Sofia schoolmaster Sava Filaretov. Those from Panagyurishte area, were recorded by Marin Drinov and Nesho Bonchev, but were sent by Vasil Cholakov. Rayko Zhinzifov, who went to Russia with the help of D. Miladinov, was another collaborator. Dimitar and Konstantin Miladinovi were aware of the great significance of the folklore in the period of the national revival and did their best to collect the best poetic writing which the Bulgarian people had created throughout the ages.

Their activity in this field is indicative of the growing interest shown towards folklore by the Bulgarian intelligentsia in the middle of the 19th century – by Vasil Aprilov, Nayden Gerov, Georgi Rakovski, Petko Slaveykov, etc. The collecting was highly assessed by its contemporaries - Lyuben Karavelov, Nesho Bonchev, Ivan Bogorov, Kuzman Shapkarev, Rayko Zhinzifov and others. The collection was met with great interest by foreign scholars. The Russian scholar Izmail Sreznevsky pointed out in 1863: "…It can be seen by the published collection that the Bulgarians far from lagging behind other peoples in poetic abilities even surpass them with the vitality of their poetry…" Soon parts of the collection were translated in Czech, Russian and German. Elias Riggs, an American linguist in Constantinople, translated nine songs into English and sent them to the American Oriental Society in Princeton, New Jersey. In a letter from in June 1862, Riggs wrote: "…The whole present an interesting picture of the traditions and fancies prevailing among the mass of the Bulgarian people…" The collection compiled by the Miladinov brothers also played a great role in the development of the modern Bulgarian literature, because its songs as poetic models for the outstanding Bulgarian poets – Ivan Vazov, Pencho Slaveikov, Kiril Hristov, Peyo Yavorov, etc.[15][16]

Controversy

Despite the Miladinov brothers were proponents of the Bulgarian national idea in Macedonia, their activity and work has been a subject of a long going dispute between parties in Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia.[17]

The Miladinovs' collection of folk songs is an evidence of their Bulgarian national consciousness.[18] However, in postwar Yugoslav Macedonia the original book "Bulgarian Folk Songs" was hidden from the general public. Suitably edited textbooks were published there into the newly codified Macedonian language, to support the promulgation of a new Macedonian nation.[19] As result the Miladinov brothers were appropriated by the historians in Communist Yugoslavia as part of Macedonian National Revival.

The collection was published in 1962 and in 1983 in Skopje under the title "The Collection of the Miladinov Brothers".[20] The reference to Macedonia as Western Bulgaria in the foreword was removed, as well as every references to Bulgarian and Bulgarians were replaced with Macedonian and Macedonians. However, after the fall of Communism, the book was published in 2000 in original, which caused serious protests of Macedonian historians.[21] As result the Macedonian State Archive displayed a photocopy of the book in cooperation with the Soros Foundation and the text on the cover was simply "Folk Songs", the upper part of the page showing "Bulgarian" has been cut off.[22]

Although Miladinov brothers regarded their language Bulgarian, Macedonian researchers today proclaim their works as early literature in Macedonian language.[23] However, there was no standardized neither Bulgarian nor Macedonian language at that time with which to conform.[24] The Bulgarian and Macedonian Slavs then worked to create a common literary standard,[25] and the publicists in the Macedonian-Bulgarian linguistic area wrote in their own local dialect called simply Bulgarian.[26] There is a similar case with the national museum of the Republic of Macedonia which, apparently, refuses to display original works by the two brothers, because of the Bulgarian labels on some of them.[6]

Honour

Miladinovi Islets near Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica are named after the brothers.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Miladinovi brothers. |

References

- ↑ "...In the meantime my efforts concerning our Bulgarian language and the Bulgarian (folk) songs, in compliance with your recommendations are unsurpassed. I have not for one moment ceased to fulfill the pledge which I made to you, Sir, because the Bulgarians are spontaneously striving for the truth. But I hope you will excuse my delay up till now, which is due to the difficulty I had in selecting the best songs and also in my work on the grammar. I hope that, on another convenient occasion, after I have collected more songs and finished the grammar, I will be able to send them to you. Please write where and through whom it would be safe to send them to you (as you so ardently wish)..."

- ↑ "...But I implore you to publish the foreword I sent you in your newspaper, adding a word or two about the songs and especially about the Western Bulgarians in Macedonia. In the foreword I have called Macedonia - Western Bulgaria (as it should be called), because the Greeks in Vienna are treating us just like sheep. They consider Macedonia a Greek province and they are not even able to understand that it is not a Greek region. But what shall we do with the Bulgarians there who are more than two million people? Surely the Bulgarians will not still be sheep with a few Greeks as their shepherds? That time has irrevocably passed and the Greeks will have to be satisfied merely with their sweet dreams. I think that the songs should be distributed chiefly among the Bulgarians, and this is why I have fixed a low price..."

- ↑ According to Shapkarev himsef: "Until then, [1857-1859, when the Miladinovs launched their educational campaign], everyone acknowledged them to be a Bulgarian."

- ↑ Nationalism, Globalization and Orthodoxy: the social origins of ethnic conflict in the Balkans, Victor Roudometof, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, ISBN 0313319499, p. 144.

- ↑ Language and National Identity in Greece, 1766-1976, Peter Mackridge, Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 019959905X, p. 189.

- 1 2 Phillips, John (2004). Macedonia: Warlords and Rebels in the Balkans. I.B.Tauris. p. 41. ISBN 186064841X.

- ↑ In their correspondence both brothers self identified as Bulgarians, see: Братя Миладинови – преписка. Издирил, коментирал и редактирал Никола Трайков (Българска академия на науките, Институт за история. Издателство на БАН, София 1964); in English: Miladinov Brothers - Correspondence. Collected, commented and redacted from Nicola Traykov, (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Historical Institute, Sofia 1964.)

- ↑ History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries, Marcel Cornis-Pope, John Neubauer, John Benjamins Publishing, 2004, ISBN 9027234558, p. 326.

- ↑ Some researchers and publicists argue that during the Ottoman period the term Bulgarian was not used to designate ethnic affiliation, rather to designate different sociocultural categories, see: The Macedonian Conflict by Loring M. Danforth.

- ↑ Developing Cultural Identity in the Balkans: Convergence Vs Divergence, Raymond Detrez, Pieter Plas, Peter Lang, 2005, ISBN 9052012970, p. 179.

- ↑ Freedom Or Death: The Life of Gotsé Delchev, Mercia MacDermott, Pluto Press, 1978, ISBN 0904526321, p. 17.

- ↑ Трайков, Н. Братя Миладинови.Преписка.1964 с. 43, 44

- ↑ Roudometof, Victor (2002). Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria and the Macedonian question. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 91. ISBN 0275976483.

- ↑ Петър Динеков, Делото на братя Милядинови. (Българска акдемия на науките, 1961 г.)

- ↑ Люлка на старата и новата българска писменост. Aкадемик Емил Георгиев, (Държавно издателство Народна просвета, София 1980)

- ↑ Петър Динеков. Делото на братя Миладинови.(Българска акдемия на науките, 1961 г.)

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. 149.

- ↑ Raymond Detrez, Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, ISBN 1442241802, p. 323.

- ↑ Who Are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000, ISBN 1850655340, p. 117.

- ↑ Миладинова, М. 140 години "Български народни песни" от братя Миладинови. Отзвук и значение. сп. Македонски преглед, 2001, Македонският научен институт, бр. 4, стр. 5-21.

- ↑ Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto; 1900 - 1996, Chris Kostov, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, pp. 93-94.

- ↑ "ms0601". www.soros.org.mk. Archived from the original on 2012-04-05. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ Michael Palairet, Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 2, From the Fifteenth Century to the Present), Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, ISBN 1443888494, p. 102.

- ↑ The Bulgarian Ministry of Education officially codified a standard Bulgarian language based on the Drinov-Ivanchev orthography in 1899, while Macedonian was finally codified in 1950 in Communist Yugoslavia, that finalized the progressive split in the common Macedonian–Bulgarian pluricentric area.

- ↑ Bechev, Dimitar (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia Historical Dictionaries of Europe. Scarecrow Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-8108-6295-6.

- ↑ From Rum Millet to Greek and Bulgarian Nations: Religious and National Debates in the Borderlands of the Ottoman Empire, 1870–1913. Theodora Dragostinova, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH.

External links

- Original edition of 'Bulgarian Folk Songs' (in Bulgarian)

- Full text of "Bulgarian folk songs" (in Bulgarian)

- Letter bearing the signature of Konstantin Miladinov

- Konstantin Miladinov poetry (in Bulgarian)

- official site of struga.org (English and Macedonian)