Mesenchymal stem cell

| Mesenchymal stem cell | |

|---|---|

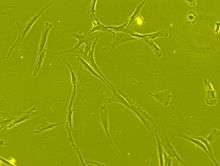

Transmission electron micrograph of a mesenchymal stem cell displaying typical ultrastructural characteristics. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cellula mesenchymatica praecursoria |

| TH | H2.00.01.0.00008 |

|

Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Mesenchymal stem cells are multipotent stromal cells that can differentiate into a variety of cell types, including osteoblasts (bone cells), chondrocytes (cartilage cells), myocytes (muscle cells) and adipocytes (fat cells which give rise to marrow adipose tissue).[1][2]

Structure

Definition

While the terms mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) and marrow stromal cell have been used interchangeably for many years, neither term is sufficiently descriptive:

- Mesenchyme is embryonic connective tissue that is derived from the mesoderm and that differentiates into hematopoietic and connective tissue, whereas MSCs do not differentiate into hematopoietic cells.[3]

- Stromal cells are connective tissue cells that form the supportive structure in which the functional cells of the tissue reside. While this is an accurate description for one function of MSCs, the term fails to convey the relatively recently discovered roles of MSCs in the repair of tissue.[4]

- The term encompasses multipotent cells derived from other non-marrow tissues, such as placenta,[5] umbilical cord blood, adipose tissue, adult muscle, corneal stroma[6] or the dental pulp of deciduous baby teeth. The cells do not have the capacity to reconstitute an entire organ.

Morphology

Mesenchymal stem cells are characterized morphologically by a small cell body with a few cell processes that are long and thin. The cell body contains a large, round nucleus with a prominent nucleolus, which is surrounded by finely dispersed chromatin particles, giving the nucleus a clear appearance. The remainder of the cell body contains a small amount of Golgi apparatus, rough endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria and polyribosomes. The cells, which are long and thin, are widely dispersed and the adjacent extracellular matrix is populated by a few reticular fibrils but is devoid of the other types of collagen fibrils.[7][8]

Location

Bone marrow

Bone marrow was the original source of MSCs, and still is the most frequently utilized. These bone marrow stem cells do not contribute to the formation of blood cells and so do not express the hematopoietic stem cell marker CD34. They are sometimes referred to as bone marrow stromal stem cells.[9]

Cord cells

The youngest and most primitive MSCs can be obtained from umbilical cord tissue, namely Wharton's jelly and the umbilical cord blood. However MSCs are found in much higher concentration in the Wharton’s jelly compared to cord blood, which is a rich source of hematopoietic stem cells. The umbilical cord is available after a birth. It is normally discarded and poses no risk for collection. These MSCs may prove to be a useful source of MSCs for clinical applications due to their primitive properties.

Adipose tissue

Adipose tissue is a rich source of MSCs (or adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells, AdMSCs).[10]

Molar cells

The developing tooth bud of the mandibular third molar is a rich source of MSCs. While they are described as multipotent, it is possible that they are pluripotent. They eventually form enamel, dentin, blood vessels, dental pulp and nervous tissues. These stem cells are capable of producing hepatocytes.

Amniotic fluid

Stem cells are present in amniotic fluid. As many as 1 in 100 cells collected during amniocentesis are pluripotent mesenchymal stem cells.[11]

Function

Differentiation capacity

MSCs have a great capacity for self-renewal while maintaining their multipotency. Beyond that, there is little that can be definitively said. The standard test to confirm multipotency is differentiation of the cells into osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondrocytes as well as myocytes and neurons. MSCs have been seen to even differentiate into neuron-like cells,[12] but there is lingering doubt whether the MSC-derived neurons are functional.[13] The degree to which the culture will differentiate varies among individuals and how differentiation is induced, e.g., chemical vs. mechanical;[14] and it is not clear whether this variation is due to a different amount of "true" progenitor cells in the culture or variable differentiation capacities of individuals' progenitors. The capacity of cells to proliferate and differentiate is known to decrease with the age of the donor, as well as the time in culture. Likewise, whether this is due to a decrease in the number of MSCs or a change to the existing MSCs is not known.

Immunomodulatory effects

Numerous studies have demonstrated that human MSCs avoid allorecognition, interfere with dendritic cell and T-cell function and generate a local immunosuppressive microenvironment by secreting cytokines.[15] Other studies contradict some of these findings, reflecting both the highly heterogeneous nature of MSC isolates and the considerable differences between isolates generated by the many different methods under development.[16]

Clinical significance

Mesenchymal stem cells in the body can be activated and mobilized if needed. However, the efficiency is low. For instance, damage to muscles heals very slowly but further study into mechanisms of MSC action may provide avenues for increasing their capacity for tissue repair.[17][18]

Autoimmune disease

Clinical studies investigating the efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells in treating diseases are in preliminary development, particularly for understanding autoimmune diseases, graft versus host disease, Crohn's disease, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis.[19][20] As of 2014, no high-quality clinical research provides evidence of efficacy, and numerous inconsistencies and problems exist in the research methods.[20]

Other diseases

Many of the early clinical successes using intravenous transplantation came in systemic diseases such as graft versus host disease and sepsis. Direct injection or placement of cells into a site in need of repair may be the preferred method of treatment, as vascular delivery suffers from a "pulmonary first pass effect" where intravenous injected cells are sequestered in the lungs.[21]

Detection

The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) has proposed a set of standards to define MSCs. A cell can be classified as an MSC if it shows plastic adherent properties under normal culture conditions and has a fibroblast-like morphology. In fact, some argue that MSCs and fibroblasts are functionally identical.[22] Furthermore, MSCs can undergo osteogenic, adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation ex vivo. The cultured MSCs also express on their surface CD73, CD90 and CD105, while lacking the expression of CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, CD79a and HLA-DR surface markers.[23]

Research

Culturing

The majority of modern culture techniques still take a colony-forming unit-fibroblasts (CFU-F) approach, where raw unpurified bone marrow or ficoll-purified bone marrow Mononuclear cell are plated directly into cell culture plates or flasks. Mesenchymal stem cells, but not red blood cells or haematopoetic progenitors, are adherent to tissue culture plastic within 24 to 48 hours. However, at least one publication has identified a population of non-adherent MSCs that are not obtained by the direct-plating technique.[24]

Other flow cytometry-based methods allow the sorting of bone marrow cells for specific surface markers, such as STRO-1.[25] STRO-1+ cells are generally more homogenous and have higher rates of adherence and higher rates of proliferation, but the exact differences between STRO-1+ cells and MSCs are not clear.[26]

Methods of immunodepletion using such techniques as MACS have also been used in the negative selection of MSCs.[27]

The supplementation of basal media with fetal bovine serum or human platelet lysate is common in MSC culture. Prior to the use of platelet lysates for MSC culture, the pathogen inactivation process is recommended to prevent pathogen transmission.[28]

Clinical trials of cryopreserved MSCs

Scientists have reported that MSCs when transfused immediately a few hours post thawing may show reduced function or show decreased efficacy in treating diseases as compared to those MSCs which are in log phase of cell growth, so cryopreserved MSCs should be brought back into log phase of cell growth in in vitro culture before these are administered for clinical trials or experimental therapies, re-culturing of MSCs will help in recovering from the shock the cells get during freezing and thawing. Various clinical trials on MSCs have failed which used cryopreserved product immediately post thaw as compared to those clinical trials which used fresh MSCs.[29] In addition, several groups reported clinical effectiveness and safety in treating osteoarthritis of knees, ankles, and hips using fresh ASCs (Adipose tissue-derived stem cells: one type of mesenchymal stem cells) in the form of adipose SVF (stromal vascular fraction) or in cultured expansion.[30]

History

In 1924, Russian-born morphologist Alexander A. Maximow used extensive histological findings to identify a singular type of precursor cell within mesenchyme that develops into different types of blood cells.[31]

Scientists Ernest A. McCulloch and James E. Till first revealed the clonal nature of marrow cells in the 1960s.[32][33] An ex vivo assay for examining the clonogenic potential of multipotent marrow cells was later reported in the 1970s by Friedenstein and colleagues.[34][35] In this assay system, stromal cells were referred to as colony-forming unit-fibroblasts (CFU-f).

The first clinical trials of MSCs were completed in 1995 when a group of 15 patients were injected with cultured MSCs to test the safety of the treatment. Since then, over 200 clinical trials have been started. However, most are still in the safety stage of testing.[5]

Subsequent experimentation revealed the plasticity of marrow cells and how their fate is determined by environmental cues. Culturing marrow stromal cells in the presence of osteogenic stimuli such as ascorbic acid, inorganic phosphate and dexamethasone could promote their differentiation into osteoblasts. In contrast, the addition of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-b) could induce chondrogenic markers.

See also

References

- ↑ Ankrum JA, Ong JF, Karp JM (March 2014). "Mesenchymal stem cells: immune evasive, not immune privileged". Nature Biotechnology. 32 (3): 252–60. doi:10.1038/nbt.2816. PMC 4320647. PMID 24561556.

- ↑ Mahla RS (2016). "Stem Cells Applications in Regenerative Medicine and Disease Therapeutics". International Journal of Cell Biology. 2016: 6940283. doi:10.1155/2016/6940283. PMC 4969512. PMID 27516776.

- ↑ Porcellini A (2009). "Regenerative medicine: a review". Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia. 31 (Suppl. 2). doi:10.1590/S1516-84842009000800017.

- ↑ Valero MC, Huntsman HD, Liu J, Zou K, Boppart MD (2012). "Eccentric exercise facilitates mesenchymal stem cell appearance in skeletal muscle". PLoS ONE. 7 (1): e29760. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029760. PMC 3256189. PMID 22253772.

- 1 2 Wang S, et al. (2012). "Clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells". Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 5 (19). doi:10.1186/1756-8722-5-19.

- ↑ Branch MJ, Hashmani K, Dhillon P, Jones DR, Dua HS, Hopkinson A (2012). "Mesenchymal stem cells in the human corneal limbal stroma". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53 (9): 5109–16. doi:10.1167/iovs.11-8673. PMID 22736610.

- ↑ Netter, Frank H. (1987). Musculoskeletal system: anatomy, physiology, and metabolic disorders. Summit, New Jersey: Ciba-Geigy Corporation. p. 134. ISBN 0-914168-88-6.

- ↑ Brighton CT, Hunt RM (1991). "Early histological and ultrastructural changes in medullary fracture callus". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 73 (6): 832–47. PMID 2071617.

- ↑ Gregory, Carl A.; Prockop, Darwin J.; Spees, Jeffrey L. (2005-06-10). "Non-hematopoietic bone marrow stem cells: Molecular control of expansion and differentiation". Experimental Cell Research. Molecular Control of Stem Cell Differentiation. 306 (2): 330–35. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.018.

- ↑ Bunnell, Bruce A.; Flaat, Mette; Gagliardi, Christine; Patel, Bindiya; Ripoll, Cynthia (2008-06-01). "Adipose-derived stem cells: Isolation, expansion and differentiation". Methods. Methods in stem cell research. 45 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.03.006. PMC 3668445. PMID 18593609.

- ↑ "What is Cord Tissue?". CordAdvantage.com.

- ↑ Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, Schwartz RE, Keene CD, Ortiz-Gonzalez XR, Reyes M, Lenvik T, Lund T, Blackstad M, Du J, Aldrich S, Lisberg A, Low WC, Largaespada DA, Verfaillie CM (2002). "Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow". Nature. 418 (6893): 41–49. doi:10.1038/nature00870. PMID 12077603.

- ↑ Franco Lambert AP, Fraga Zandonai A, Bonatto D, Cantarelli Machado D, Pêgas Henriques JA (2009). "Differentiation of human adipose-derived adult stem cells into neuronal tissue: Does it work?". Differentiation. 77 (3): 221–28. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2008.10.016. PMID 19272520.

- ↑ Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE (2006). "Matrix Elasticity Directs Stem Cell Lineage Specification". Cell. 126 (4): 677–89. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. PMID 16923388.

- ↑ Ryan JM, Barry FP, Murphy JM, Mahon BP (2005). "Mesenchymal stem cells avoid allogeneic rejection". Journal of Inflammation. 2: 8. doi:10.1186/1476-9255-2-8. PMC 1215510. PMID 16045800.

- ↑ Phinney DG, Prockop DJ (2007). "Concise Review: Mesenchymal Stem/Multipotent Stromal Cells: The State of Transdifferentiation and Modes of Tissue Repair-Current Views". Stem Cells. 25 (11): 2896–902. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0637. PMID 17901396.

- ↑ Heirani-Tabasi A, Hassanzadeh M, Hemmati-Sadeghi S, Shahriyari M, Raeesolmohaddeseen M (2015). "Mesenchymal Stem Cells; Defining the Future of Regenerative Medicine". Journal of Genes and Cells. 1 (2): 34–39. doi:10.15562/gnc.15.

- ↑ Anderson, Johnathon D.; Johansson, Henrik J.; Graham, Calvin S.; Vesterlund, Mattias; Pham, Missy T.; Bramlett, Charles S.; Montgomery, Elizabeth N.; Mellema, Matt S.; Bardini, Renee L. (2016-03-01). "Comprehensive Proteomic Analysis of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes Reveals Modulation of Angiogenesis via Nuclear Factor-KappaB Signaling". Stem Cells. 34 (3): 601–13. doi:10.1002/stem.2298. ISSN 1549-4918. PMID 26782178.

- ↑ Figueroa FE, Carrión F, Villanueva S, Khoury M (2012). "Mesenchymal stem cell treatment for autoimmune diseases: a critical review". Biol. Res. 45 (3): 269–77. doi:10.4067/S0716-97602012000300008. PMID 23283436.

- 1 2 Sharma RR, Pollock K, Hubel A, McKenna D (2014). "Mesenchymal stem or stromal cells: a review of clinical applications and manufacturing practices". Transfusion. 54 (5): 1418–37. doi:10.1111/trf.12421. PMID 24898458.

- ↑ Fischer UM, Harting MT, Jimenez F, Monzon-Posadas WO, Xue H, Savitz SI, Laine GA, Cox CS (2009). "Pulmonary Passage is a Major Obstacle for Intravenous Stem Cell Delivery: The Pulmonary First-Pass Effect". Stem Cells and Development. 18 (5): 683–92. doi:10.1089/scd.2008.0253. PMC 3190292. PMID 19099374.

- ↑ Hematti P (2012). "Mesenchymal stromal cells and fibroblasts: a case of mistaken identity?". Cytotherapy. 14 (5): 516–21. doi:10.3109/14653249.2012.677822. PMID 22458957.

- ↑ Dominici M; Le Blanc K; Mueller I; Slaper-Cortenbach I; Marini F; Krause D; Deans R; Keating A; Prockop Dj; Horwitz E (1 January 2006). "Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement". Cytotherapy. 8 (4): 315–17. doi:10.1080/14653240600855905. PMID 16923606.

- ↑ Wan C, He Q, McCaigue M, Marsh D, Li G (2006). "Nonadherent cell population of human marrow culture is a complementary source of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)". Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 24 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1002/jor.20023. PMID 16419965.

- ↑ Gronthos S, Graves SE, Ohta S, Simmons PJ (1994). "The STRO-1+ fraction of adult human bone marrow contains the osteogenic precursors". Blood. 84 (12): 4164–73. PMID 7994030.

- ↑ Oyajobi BO, Lomri A, Hott M, Marie PJ (1999). "Isolation and Characterization of Human Clonogenic Osteoblast Progenitors Immunoselected from Fetal Bone Marrow Stroma Using STRO-1 Monoclonal Antibody". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 14 (3): 351–61. doi:10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.3.351. PMID 10027900.

- ↑ Tondreau T, Lagneaux L, Dejeneffe M, Delforge A, Massy M, Mortier C, Bron D (1 January 2004). "Isolation of BM mesenchymal stem cells by plastic adhesion or negative selection: phenotype, proliferation kinetics and differentiation potential". Cytotherapy. 6 (4): 372–79. doi:10.1080/14653240410004943. PMID 16146890.

- ↑ Iudicone P, Fioravanti D, Bonanno G, Miceli M, Lavorino C, Totta P, Frati L, Nuti M, Pierelli L (Jan 2014). "Pathogen-free, plasma-poor platelet lysate and expansion of human mesenchymal stem cells". J Transl Med. 12: 28. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-12-28. PMC 3918216. PMID 24467837.

- ↑ François M, Copland IB, Yuan S, Romieu-Mourez R, Waller EK, Galipeau J (2012). "Cryopreserved mesenchymal stromal cells display impaired immunosuppressive properties as a result of heat-shock response and impaired interferon-γ licensing". Cytotherapy. 14 (2): 147–52. doi:10.3109/14653249.2011.623691. PMC 3279133. PMID 22029655.

- ↑ Pak, J.; Lee, J. H.; Pak, N.; Pak, Y.; Park, K. S.; Jeon, J. H.; Jeong, B. C.; Lee, S. H. (2018). "Cartilage Regeneration in Humans with Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells and Adipose Stromal Vascular Fraction Cells: Updated Status". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 19: 2146. doi:10.3390/ijms19072146.

- ↑ Stewart Sell (2013-08-16). Stem Cells Handbook. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-4614-7696-2.

- ↑ Becker AJ, McCulloch EA, Till JE (1963). "Cytological Demonstration of the Clonal Nature of Spleen Colonies Derived from Transplanted Mouse Marrow Cells". Nature. 197 (4866): 452–54. doi:10.1038/197452a0. PMID 13970094.

- ↑ Siminovitch L, Mcculloch EA, Till JE (1963). "The distribution of colony-forming cells among spleen colonies". Journal of Cellular and Comparative Physiology. 62 (3): 327–36. doi:10.1002/jcp.1030620313. PMID 14086156.

- ↑ Friedenstein AJ, Deriglasova UF, Kulagina NN, Panasuk AF, Rudakowa SF, Luriá EA, Ruadkow IA (1974). "Precursors for fibroblasts in different populations of hematopoietic cells as detected by the in vitro colony assay method". Experimental hematology. 2 (2): 83–92. PMID 4455512.

- ↑ Friedenstein AJ, Gorskaja JF, Kulagina NN (1976). "Fibroblast precursors in normal and irradiated mouse hematopoietic organs". Experimental hematology. 4 (5): 267–74. PMID 976387.

External links

- Mesenchymal stem cells fact sheet, published June 2012, scientist-reviewed and not too technical

- Mesenchymal Stem Cell Research at Johns Hopkins University

- Murphy MB, Moncivais K, Caplan AI (2013). "Mesenchymal stem cells: environmentally responsive therapeutics for regenerative medicine". Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 45 (11): e54. doi:10.1038/emm.2013.94. PMC 3849579. PMID 24232253.