Marriage in the United States

Marriage in the United States is a legal, social, and religious institution. The legal recognition of marriage is regulated by individual states, each of which sets an "age of majority" at which individuals are free to enter into marriage solely on their own consent, as well as at what ages underage persons are able to marry with parental and/or judicial consent. Marriage laws have changed considerably during United States history, including the removal of bans on interracial marriage and same-sex marriage. In 2009, there were 2,077,000 marriages, according to the Census bureau.[1] The median age for the first marriage has increased in recent years.[2] The median age in the early 1970s was 23 for men and 21 for women; and it rose to 28 for men and 26 for women by 2009[3] and by 2017, it was 29.5 for men and 27.4 for women.[4]

Marriages vary considerably in terms of religion, socioeconomic status, age, commitment, and so forth.[5][6] Reasons for marrying may include a desire to have children, love, or economic security.[7] Marriage has been a means in some instances to acquire citizenship by getting a green card; the Immigration Marriage Fraud Amendments of 1986 established laws to punish such instances.[8] In 2003, 184,741 immigrants were admitted as spouses of United States citizens.[9]

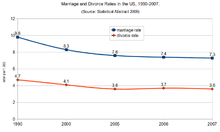

Marriages can be terminated by annulment, divorce or death of a spouse. Divorce (known as dissolution of marriage in some states) laws vary by state, and address issues such as how the two spouses divide their property, how children will be cared for, and support obligations of one spouse toward the other. In the last 50 years, divorce has become more prevalent. In 2005, it was estimated that 20% of marriages would end in divorce within five years.[10] Divorce rates in 2005 were four times the divorce rates in 1955, and a quarter of children less than 16 years old are raised by a stepparent.[10] Marriages that end in divorce last for a median of 8 years for both men and women.[11]

As a rough rule, marriage has more legal ramifications than other types of bonds between consenting adults. A civil union is "a formal union between two people of the same or of different genders which results in, but falls short of, marriage-like rights and obligations," according to one view.[12] Domestic partnerships are a version of civil unions. Registration and recognition are functions of states, localities, or employers; such unions may be available to couples of the same sex and, sometimes, opposite sex.[13] Cohabitation is when two unmarried people who are in an intimate relationship live together.[14]

History

The marriage between Luisa de Abrego, a free black domestic servant from Seville and Miguel Rodríguez, a white Segovian conquistador in 1565 in St. Augustine (Spanish Florida), is the first known and recorded Christian marriage anywhere in what is now the continental United States.[15]

When the country was founded in the eighteenth century, marriage between whites and non-whites was largely forbidden due to the racist attitudes of the time. In 1948, the California Supreme Court became the first state high court to declare a ban on interracial marriage unconstitutional. In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down remaining interracial marriage laws nationwide, in the case Loving v. Virginia.[16]

Expectations of a marriage partner have changed over time. Second U.S. President John Adams wrote in his diary that the ideal spouse was willing to "palliate faults and mistakes, to put the best construction upon words and actions, and to forgive injuries."[17] In 1940, the University of Pennsylvania conducted a study about premarital sex life. Male students who participated had great difficulty in facing marriage with a girl who had had sexual relations.[18]

Demographics

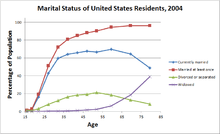

Marital status by age group in 2004

In 2004 the U.S. Census Bureau measured the marital status of U.S. residents, showing several trends.[19][20] While about 96% of residents in their 70s and 80s were married at least once, many were widowed due to the death of their spouses. In addition, a large portion of middle-aged Americans are either divorced, legally separated, or informally separated. Of those who were "separated or divorced," approximately 74% were legally divorced, 15% were "separated," and 11% were listed as having an "absent spouse."

Marital status in the U.S. in the year 2000

The four maps on the right shows the pattern of married, widowed, separated, and divorced households in the United States in the year 2000. The map on the bottom left shows that the west coast had the highest percentages of households to go through divorce. According to the map bottom right of the census chart the south east coast and New Orleans had the highest percentage of separated houses in the U.S. The northeast had the highest percentages of marriages...The highest percentages of widowed households was in the Midwest.

Trends and census data of 2006-2010

As of 2006, 55.7% of Americans age 18 and over were married.[21] According to the 2008-2010 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates, 51.5% of males and 47.7% of females over the age of 15 were married. The separation rate was 1.8% for males and 0.1% for females.[2]

African Americans have married the least of all of the predominant ethnic groups in the U.S. with a 29.9% marriage rate, but have the highest separation rate which is 4.5%. This results in a high rate of single mother households among African Americans compared with other ethnic groups (White, African American, Native Americans, Asian, Hispanic).[2] This can lead a child to become closer to their mother, the only caregiver. Yet with only one parent furnishing resources, economic stress can result.[22] Native Americans have the second lowest marriage rate with 37.9%. Hispanics have a 45.1% marriage rate, with a 3.5% separation rate.[2]

In the United States, the two ethnic groups with the highest marriage rates included Asians with 58.5% and Whites with 52.9%. Asians have the lowest rate of divorce among the main groups with 1.8%. Whites, African Americans, and Native Americans have the highest rates of being widowed ranging from 5%-6.5%. They also have the highest rates of divorce among the three, ranging from 11%-13% with Native Americans having the highest divorce rate.[2]

In 2009, 2,077,000 marriages occurred in the United States.[1] The median age for Americans' first marriage has risen in recent years,[2] with the median age at first marriage in the early 1970s being 21 for women and 23 for men, and in 2009, it had risen to 26 for women and 28 for men.[3][23]

According to the 2010 U.S. Census Bureau, the average family income is higher than previous years at $62,770.[24] The percentage of family households below the poverty line in 2011 was 15.1%, higher than in 2000 when it was 11.3%.[25] According to a report in 2013, the percentage of heterosexual couples who marry has fallen dramatically, but couples who marry are more likely to have college degrees and higher income than those who do not marry.[26] Some sociologists suggest that marriage in twenty-first century America has become a luxury good.[26]

Sociology of marriage

Types of marriage

Monogamy is when one person marries one other person and is the most common and accepted form of marriage in the United States.[6] Serial monogamy is when individuals are permitted to marry again, often on the death of the first spouse or after divorce; they cannot have more than one spouse at one time because that would be polygamy which in countries with marital monogamy like the US is called bigamy.[6][27] Polygamy is a form of marriage in which someone marries multiple people at a given time,[6] and is illegal throughout the U.S. under the Edmunds Act.[28] Part of the function of looking at marriage from a sociological perspective is to give insight into the reasons behind various marital arrangements.

Reasons for marriage

There are several reasons that Americans marry. The desire to have children is one; having a family is a high priority among many Americans.[7] People also desire love, companionship, commitment, continuity, and permanence.[7] There are some reasons for marriage that are ephemeral. These reasons include social legitimacy, social pressure, the desire for a high social status, economic security, rebellion or revenge, or validation of an unplanned pregnancy.[7]

U.S. Federal Income Tax advantage: "For 2014, single taxpayers are allowed a standard deduction of $6,200, while married couples filing a joint return are allowed a deduction of $12,400."[29]

Wedding ceremonies

Most wedding traditions were assimilated from other, generally European, countries.[30] Marriages in the U.S. are typically arranged by the participants and ceremonies may either be religious or civil. There was a tradition that the prospective bridegroom ask his future father-in-law for his blessing, but this is rarely observed today.[30] When it is the first wedding for the bride, a typical U.S. wedding tends to be more elaborate.

In a traditional wedding, the bride and groom invite all of their family and friends. Those with the closest relationships to the couple are selected to be bridesmaids and groomsmen, with the closest of each selected to be the maid of honor and best man.[30] The couple may add a list of desired gifts—usually necessities for a new household, such as dishes and bedding—to a bridal registry.

Weeks before the wedding, the maid of honor plans a wedding shower, where the bride-to-be receives gifts from family and friends.[30] The best man often organizes a bachelor party shortly before the wedding, where male friends join the groom in a "last night of freedom" from the responsibilities of marriage.

Traditionally, a U.S. wedding would take place in a religious building such as a church, with a religious leader officiating the ceremony. During the ceremony, the bride and groom vow their love and commitment for one another with church-provided vows.[30] The officiant asks the guests if they know of any reason why the couple should not be married.[30] If no one objects, the couple then exchanges rings, which symbolizes their never-ending love and commitment towards one another.[30] Finally, for the first time in public, the couple is pronounced husband and wife. It is then that they share their first kiss as a married couple and thus seal their union.[30] The couple leaves the building, and family and friends throw rice or wheat their way, which symbolizes fertility.[30]

After the actual wedding ceremony itself, there may be a wedding reception.[30] During this reception it is tradition that the best man and the maid of honor proposes a toast.[30] The couple may receive gifts.[30] The couple then usually goes on a honeymoon to celebrate their marriage, which lasts several days or weeks.[30]

Modern weddings often deviate from these traditions. The bride and her female friends may enjoy a bachelorette party to match the men's bachelor party. Weddings are sometimes held outdoors or in other buildings instead of churches, and officiants may not be religious leaders but other people licensed by the state. The religious vows may be replaced by vows written by the couple themselves, and most venues today discourage the throwing of rice and encourage the use of birdseed or grass seed. Other traditional elements of a wedding may be changed or omitted, and weddings may even vary wildly in format from the traditional template.

As of 2012, the median cost of a wedding, including both the ceremony and reception, but not the honeymoon, in the United States, was about US $18,000 per wedding, according to a large survey at an online wedding website.[31] Regional differences are significant, with residents of Manhattan paying more than three times the median, while residents of Alaska spent less than half as much.[31] Additionally, the survey probably overestimates the typical cost because of a biased sample population.[31]

Law

Marriage laws are established by individual states.[32] There are two methods of receiving state recognition of a marriage: common law marriage and obtaining a marriage license.[33] Common-law marriage is no longer permitted in most states.[32] Though federal law does not regulate state marriage law, it does provide for rights and responsibilities of married couples that differ from those of unmarried couples. Reports published by the General Accounting Office in 1997 and 2004 identified over 1000 such laws.[34]

Marriage as a fundamental right

The United States Supreme Court has in at least 15 cases since 1888 ruled that marriage is a fundamental right. These cases are:[35][36]

- Maynard v. Hill, 125 U.S. 190 (1888) Marriage is "the most important relation in life" and "the foundation of the family and society, without which there would be neither civilization nor progress."

- Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923) The right "to marry, establish a home and bring up children" is a central part of liberty protected by the Due Process Clause.

- Skinner v. Oklahoma ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) Marriage is "one of the basic civil rights of man" and "fundamental to the very existence and survival of the race."

- Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) "We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights—older than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage is a coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to the degree of being sacred. It is an association that promotes a way of life, not causes; a harmony in living, not political faiths; a bilateral loyalty, not commercial or social projects. Yet it is an association for as noble a purpose as any involved in our prior decisions."

- Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) "The freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men."

- Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 (1971) "[M]arriage involves interests of basic importance to our society" and is "a fundamental human relationship."

- Cleveland Board of Education v. LaFleur, 414 U.S. 632 (1974) "This Court has long recognized that freedom of personal choice in matters of marriage and family life is one of the liberties protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment."

- Moore v. City of East Cleveland, 431 U.S. 494 (1977) "[W]hen the government intrudes on choices concerning family living arrangements, this Court must examine carefully the importance of the governmental interests advanced and the extent to which they are served by the challenged regulation."

- Carey v. Population Services International, 431 U.S. 678 (1977) "[I]t is clear that among the decisions that an individual may make without unjustified government interference are personal decisions relating to marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, and child rearing and education."

- Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374 (1978) "[T]he right to marry is of fundamental importance for all individuals."

- Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987) "[T]he decision to marry is a fundamental right" and an "expression[ ] of emotional support and public commitment."

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992) "Our law affords constitutional protection to personal decisions relating to marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, child rearing, and education. [...] These matters, involving the most intimate and personal choices a person may make in a lifetime, choices central to personal dignity and autonomy, are central to the liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. At the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life."

- M.L.B. v. S.L.J., 519 U.S. 102 (1996) "Choices about marriage, family life, and the upbringing of children are among associational rights this Court has ranked as 'of basic importance in our society,' rights sheltered by the Fourteenth Amendment against the State's unwarranted usurpation, disregard, or disrespect."

- Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) "[O]ur laws and tradition afford constitutional protection to personal decisions relating to marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, and education. ... Persons in a homosexual relationship may seek autonomy for these purposes, just as heterosexual persons do."

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ___ (2015) "[T]he right to marry is a fundamental right inherent in the liberty of the person, and under the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment couples of the same-sex may not be deprived of that right and that liberty."

Age of marriage

The age at which a person can marry varies by state. The marriage age is generally 18 years, with the exception of Nebraska (19) and Mississippi (21). In addition, all states, except Delaware, allow minors to marry in certain circumstances, such as parental consent, judicial consent, pregnancy, or a combination of these situations. Most states allow minors aged 16 and 17 to marry with parental consent alone. 30 states have set an absolute minimum age by statute,[37] which varies between 13 and 18, while in 20 states there is no statutory minimum age if other legal conditions are met. In states with no set minimum age, the traditional common law minimum age is 14 for boys and 12 for girls - ages which have been confirmed by case law in some states.[38] Over the past 15 years, more than 200,000 minors married in the US, and in Tennessee a 10-year-old girl was married in 2001,[39] before the state finally set a minimum age of 17 in 2018.[40]

Restrictions and expansions of marriage

Marriage has been restricted over the course of the history of the United States according race, sexual orientation, number of parties entering into the marriage, and familial relationships.

Common-law marriage

Eight states and the District of Columbia recognise common-law marriages. Once they meet the requirements of the respective state, couples in those recognised common-law marriages are considered legally married for all purposes and in all circumstances.[41] Common-law marriage can be contracted in Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, and the District of Columbia.[42][43] Common law marriage may also be valid under military law for purposes of a bigamy prosecution under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.[44]

All U.S. jurisdictions recognize common-law marriages that were validly contracted in the originating jurisdiction, because they are valid marriages in the jurisdiction where they were contracted, because of the Full Faith and Credit Clause. However, absent legal registration or similar notice of the marriage, the parties to a common law marriage or their eventual heirs may have difficulty proving their relationship to be marriage. Some states provide for registration of an informal or common-law marriage based on the declaration of each of the spouses on a state-issued form.[45]

Marriage law and race

Anti-miscegenation laws which prohibited interracial marriage date back to Colonial America. The earliest were established in Maryland and Virginia in the 1660s. After independence, seven of the original colonies and many new states, particularly those in the West and the South, also implemented anti-miscegenation laws. Despite a number of repeals in the 19th century, in 1948, 30 out of 48 states enforced prohibitions against interracial marriage. A number of these laws were repealed between 1948 and 1967. In 1948, the California Supreme Court ruled the Californian anti-miscegenation statute unconstitutional in Perez v. Sharp. Many other states repealed their laws in the following decade, with the exception of states in the South. In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court declared all anti-miscegenation laws unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia.

Marriage law and sexual orientation

For much of the United States's history, marriage was restricted to heterosexual couples. In 1993, three same-sex couples challenged the legality Hawaii's statute prohibiting gay marriage in the lawsuit Baehr v. Miike. The case brought same-sex marriage to national attention and spurred the creation of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996, which denied federal recognition of same-sex marriages and defined marriage to be between one man and one woman. In 2013, the United States Supreme Court ruled that Section 3 of DOMA was unconstitutional in the case of United States v. Windsor.

In 2004, Massachusetts became the first state to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. In reaction, many states took measures to define marriage as existing between one man and one woman. By 2012, 31 states had amended their constitutions to prevent same-sex marriage, and 6 had legalized it. Bolstered by the repeal of DOMA, an additional 30 states legalized same-sex marriage between 2012 and 2015. On June 26, 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court declared all state bans on same-sex marriage unconstitutional in Obergefell v. Hodges.

Polygamy

Polygamy (or bigamy) is illegal in all 50 states,[28] as well as the District of Columbia, Guam,[46] and Puerto Rico.[47] Bigamy is punishable by a fine, imprisonment, or both, according to the law of the individual state and the circumstances of the offense.[48] Because state laws exist, polygamy is not actively prosecuted at the federal level,[49] but the practice is considered "against public policy" and, accordingly, the U.S. government does not recognize bigamous marriages for immigration purposes (that is, would not allow one of the spouses to petition for immigration benefits for the other), even if they are legal in the country where a bigamous marriage was celebrated.[50] Any immigrant coming to the United States to practice polygamy will not be admitted.[51]

Many US courts (e.g. Turner v. S., 212 Miss. 590, 55 So.2d 228) treat bigamy as a strict liability crime: in some jurisdictions, a person can be convicted of a felony even if he or she reasonably believed he or she had only one legal spouse. For example, a person who mistakenly believes that their spouse is dead or that their divorce is final can still be convicted of bigamy if they marry a different person.[52]

Polygamy became a significant social and political issue in the United States in 1852, when The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) made it known that a form of the practice, called plural marriage, was part of its doctrine. Opposition to the practice by the United States government resulted in an intense legal conflict, and resulted in it being outlawed federally by the Edmunds Act in 1882. The LDS Church president Wilford Woodruff announced the church's official abandonment of the practice on September 25, 1890.[53] However, breakaway Mormon fundamentalist groups living mostly in the western United States, Canada, and Mexico still practice plural marriage.

Some other Americans practice polygamy including some American Muslims.[54]

Other restrictions

Marriage between first cousins is illegal in most states. However, it is legal in some states, the District of Columbia and some territories. Some states have some restrictions or exceptions for first cousin marriages and/or recognize such marriages performed out-of-state.

Marriage and immigration

According to the United States Census Bureau "Every year over 450,000 United States citizens marry foreign-born individuals and petition for them to obtain a permanent residency (Green Card) in the United States."[55] In 2003, 184,741 immigrants were admitted to the U.S. as spouses of U.S. citizens.[9]

There are conditional requirements in order to obtain a green card through the marriage process. The prospect must have a conditional green card. This becomes permanent after approval by the government. The candidate may then apply for United States citizenship.[56]

A conditional residence green card is given to applicants who are being processed for permanent residence in the United States because they are married to a U.S. citizen. It is valid for two years. At the end of this time period if the card holder does not change the status of their residency they will be put on "out of status". Legal action by the government may follow.[57]

There are different procedures based on whether the applicant is already a U.S. citizen or if the applicant is an immigrant. The marriage must also be legal in, if appropriate, the emigrant's country.[56]

Immigration Marriage Fraud Amendments of 1986

Public Law 99-639 (Act of 11/10/86) was passed to deter marriage fraud among immigrants. The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services summarizes the law and its implications: "Its major provision stipulates that aliens deriving their immigrant status based on a marriage of less than two years are conditional immigrants. To remove their conditional status the immigrants must apply at a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services office during the 90-day period before their second-year anniversary of receiving conditional status. If the aliens cannot show that the marriage through which the status was obtained was and is a valid one, their conditional immigrant status may be terminated and they may become deportable."[8]

The conditional immigration status can be terminated for several causes, including divorce, invalid marriage, and failure to petition Immigration Services to remove the classification of conditional residency. If Immigration Services suspects that an alien has created a fraudulent marriage the immigrant is subject to removal from the United States. The marriage must be fraudulent at its inception, as can be determined by several factors. The factors include the conduct of parties before and after the marriage, and the bride and groom's intention of establishing a life together. The validity must be proved by the couple by showing insurance policies, property, leases, income tax, bank accounts, etc. Cases are decided by determining whether the sole purpose of the marriage was to gain benefits for the immigrant.

The punishment for fraud is a large monetary penalty and the possibility of never becoming a permanent resident of the United States. According to the statute, "Any individual who knowingly enters into a marriage for the purpose of evading any provision of the immigration laws shall be imprisoned for not more than 5 years, or fined not more than $250,000, or both" (I.N.A. § 275(c); 8 U.S.C. § 1325(c)). The U.S. citizen or resident spouse could also face criminal prosecution, including fines or imprisonment. They could be prosecuted for either criminal conspiracy (see U.S. v. Vickerage, 921 F.2d 143 (8th Cir. 1990)) or for establishing a “commercial enterprise” to fraudulently acquire green cards for immigrants (see I.N.A. § 275(d); 8 U.S.C. § 1325(d)).[58]

These Amendment Acts cover spouses, children of spouses, and K-1 visa fiancés.[8]

Basic immigration law

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 has been amended many times, but still remains the basic and central body of immigration law.[59]

Intersection of immigration law and family law

Immigrants who use the reason of family ties to gain entry into the United States are required to document financial arrangements. The sponsor of a related immigrant must guarantee financial support to the family.[60] These guarantees form a contract between a sponsor and the federal government. It requires the sponsor to support the immigrant relative at a level equivalent to 125% of the poverty line for his or her household size. A beneficiary of the contract, the immigrant, or the Federal Government may sue for the promised support in the event the sponsor does not fulfill the obligations of the contract. The sponsor is also liable for the prevailing party's legal expenses.[61]

Divorce does not end the sponsor's obligation to provide the support deemed by the contract. The only ways to terminate the obligation are the immigrant spouse becomes a U.S. citizen, the immigrant spouse has worked forty Social Security Act eligible quarters (10 years), the immigrant spouse is no longer considered a permanent alien and has left the U.S., the immigrant spouse obtained an ability to adjust their status, or the immigrant spouse dies. A sponsor's death also cuts off the obligation, but not in regards to any support the sponsor already owes which will be paid but the sponsor's estate.[61]

Mail-order bride and immigration fraud

A mail-order bride is a foreign woman who contacts American men and immigrates for the purpose of marriage.

Initially, it was conducted through mailed catalogs, but now, more often, on the internet. Prospective brides are typically from developing nations such as South/Southeast Asia, the Philippines, Thailand, Sri Lanka, India, Taiwan, Macao, Hong Kong, and China. Brides from Eastern European countries have been in demand.[62] The mail-order bride phenomenon can be traced as far back as the 1700s and 1800s.[63] This was due to the immigration of European colonizers who were in far away areas and wanted brides from their homeland.[63]

First world governments have speculated that another reason for foreign women, marrying men in their country, is to provide an easy immigration route by staying married for a period of time sufficient to secure permanent citizenship, and then divorce their husbands. Whether the brides choose to remain married or not, they could still sponsor the rest of their families to immigrate. Precautions have been taken by several countries such as the United States, Great Britain, and Australia. They have fought the proliferation of the mail-order bride industry through amending immigration laws. The United States addressed the mail-order bride system by passing the Immigration Marriage Fraud Amendment of 1986.[64] Great Britain and Australia have experienced similar problems and are trying to deal with the issue.[62]

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender immigrants

In 2000, 36,000 same-sex bi-national couples were living in the United States. A majority of these couples were raising young children.[65] Females constitute 58% of bi-national families; 33% are male bi-national.[65]

History

The revision of American immigration law imposed a ban on homosexual people began in 1952.[65] The language barred "aliens afflicted with psychopathic personality, epilepsy or mental defect."[65] Congress explicitly intended this language to cover "homosexuals and sex perverts." The law was amended in 1965 to more specifically prohibit the entry of persons "afflicted with... sexual deviation."[65] Until 1990, "sexual deviation" was grounds for exclusion from the United States, and anyone who admitted being a homosexual was refused entry.[65] Lesbian and gay individuals are now admitted and US citizens may petition for immigrant visas for their same-sex spouses under the same terms as opposite-sex spouses.[66]

Boutilier v. Immigration Service, 1967

In 1967, the Supreme Court confirmed that, when describing a homosexual person, they were to be referred to as a "psychopathic personality."[65] Twenty-one-year-old Clive Boutilier, a Canadian, had moved to the United States in 1955 to join his mother, stepfather, and 3 siblings who already lived there.[65] In 1963, he applied for US citizenship, admitting that he had been arrested on a sodomy charge in 1959.[65] He was ordered to be deported. He challenged his deportation until it became a federal matter and became a case for the Supreme Court. In a six-three decision, the court ruled that Congress had decided to bar gay people from entering the United States:[65] "Congress was not laying down a clinical test, but an exclusionary standard which it declared to be inclusive of those having homosexual and perverted characteristics..." Congress used the phrase 'psychopathic personality' not in the clinical sense, but to effectuate its purpose to exclude from entry all homosexuals and other sex perverts."[65] Boutilier was torn from his partner of eight years. According to one historian, "Presumably distraught about the Court's Decision... Boutillier attempted suicide before leaving New York, survived a month-long coma that left him brain-damaged with permanent disabilities, and moved to southern Ontario with his parents, who took on the task of caring for him for more than twenty years."[65] He died in Canada on April 12, 2003, only weeks before that country moved to legalize same-sex marriage.[65]

Even with the ban being enforced homosexual people still managed to come to the United States for several reasons, but especially to be with the people they loved.[65] The fight to allow homosexual immigrants into the United States continued in the mid-1970 with an Australian national named Anthony Sullivan.[65] He was living in Boulder, Colorado, with his American partner, Richard Adams.[65] When Sullivan's visitor's visa was about to expire, they managed to persuade the county clerk to issue them a marriage license, with which Sullivan applied for a green card as Adams' spouse.[65] They received a negative reply from the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Sullivan and Adams sued, and in 1980, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that because Congress intended to restrict the term "spouse" to opposite-sex couples, and because Congress has extensive power to limit access to immigration benefits, the denial was lawful.[65] The ban was finally repealed in 1990, but without making any provision for gays and lesbians to be treated equally with regard to family-based immigration sponsorship.[65] Sponsorship [66] became possible only after the 2013 US Supreme Court decision in US v Windsor [67] that struck down a provision to the contrary in the Defense of Marriage Act.

Family reunification

Two-thirds of legal immigrants to the United States arrive on family-based petitions, sponsored by a fiancé, spouse, parent, adult child, or sibling. "Family reunification" lies at the heart of the U.S. immigrations system. However, separating same-sex couples is a principle Congress favors. In 1996, Congress passed the Defense of Marriage Act, which forbids recognizing same-sex partners as spouses or family members for any federal purpose, including immigration. Despite the gains that same-sex couples have made on the local level in some states, same-sex couples are not eligible for immigration benefits. Immigration recognition is completely controlled by the federal government, which recognizes as valid same-sex marriages that were valid in the jurisdiction where they were contracted, whether in the US or abroad.[66]

Divorce

Divorce is the province of state governments, so divorce law varies from state to state. Prior to the 1970s, divorcing spouses had to prove that the other spouse was at fault, for instance for being guilty of adultery, abandonment, or cruelty; when spouses simply could not get along, lawyers were forced to manufacture "uncontested" divorces. The implementation of no-fault divorce began in 1969 in California and became nationwide with the passage of New York's law in 2010. No-fault divorce (on the grounds of "irreconcilable differences", "irretrievable breakdown of marriage", "incompatibility", or after a separation period etc.) is now available in all states. State law provides for child support where children are involved, and sometimes for alimony.[68]

Relevant types of unions

Domestic partnerships

Domestic partnerships are a version of civil unions. Registration and recognition are functions of states, localities, or employers; such unions may be available to couples of the same sex and, sometimes, opposite sex.[13] Although similar to marriage, a domestic partnership does not confer the 1,138 rights, privileges, and obligations afforded to married couples by the federal government, but the relevant state government may offer parallel benefits.[13] Because domestic partnerships in the United States are determined by each state or local jurisdictions, or employers, there is no nationwide consistency on the rights, responsibilities, and benefits accorded domestic partners.[13] Some couples enter into a private, informal, documented domestic partnership agreement, specifying their mutual obligations because the obligations are otherwise merely implied, and written contracts are much more valid in legal circumstances.[13]

Cohabitation

Cohabitation occurs when two unmarried people who are in an intimate relationship live together.[14] Some couples cohabit as a way to experience married life before they are actually married. Some cohabit instead of marrying. Other couples may live together because other living arrangements are less desired. In the past few decades, societal standards that discouraged cohabitation have faded and cohabiting is now considered more acceptable.[69]

Children of cohabiting, instead of married, parents may have less stability in their lives. In 2011, The National Marriage Project reported that about two-thirds of children with cohabiting parents saw them break up before they were 12 years old. About a quarter of children of married couples had experienced this by age 12.[70]

See also

References

- 1 2 "U.S. Census – Marriages and Divorces Number and Rate by State: 1990 to 2009" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder2.census.gov.

- 1 2 Marantz Henig, Robin (August 18, 2010). "What Is It About 20-Somethings?". The New York Times. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ↑ Abigail Geiger, Gretchen Livingston (February 13, 2018), 8 facts about love and marriage in America, Pew Research

- ↑ Nielsen, Arthur; William Pinsof (October 2004). "Marriage 101: An Integrated Academic and Experiential Undergraduate Marriage Education Course". Family Relations. 53 (5): 485–494. doi:10.1111/j.0197-6664.2004.00057.x. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Jeanne H. Ballantine; Keith A. Roberts (2009). Our Social World: Condensed Version. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-4129-6659-7. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Nadelson, Carol; Malkah Notman (October 1, 1981). "To Marry or Not to Marry: A Choice". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 138 (10): 1352–1356. doi:10.1176/ajp.138.10.1352. PMID 7294193. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Immigration Marriage Fraud Amendments of 1986". Retrieved November 11, 2011. , Immigration Marriage Fraud Amendments of 1986.

- 1 2 Statistical Abstract of the United ... - Census Bureau - Google Books. Books.google.com. 2006. ISBN 978-0-934213-94-3. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- 1 2 Brian K. Williams, Stacy C. Sawyer, Carl M. Wahlstrom, Marriages, Families & Intimate Relationships, 2005

- ↑ https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p70-125.pdf

- ↑ Lloyd Duhaime. "Civil Union Definition". Duhaime.org Learn Law. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Warner, Ralph; Toni Ihara; Frederick Hertz (2008). Living Together: A Legal Guide for Unmarried Couples. United States of America: Consolidated Printers. pp. 7, 8. ISBN 978-1-4133-0755-9.

- 1 2 Nazio, Tiziana (2008). Cohabitation, family, and society. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-415-36841-4. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ↑ J. Michael Francis, PhD, Luisa de Abrego: Marriage, Bigamy, and the Spanish Inquisition, University of South Florida

- ↑ "Marriage A History of Change" (PDF). GLAD. 2011

- ↑ Coontz, Stephanie (2005). Marriage, a history: from obedience to intimacy or how love conquered marriage. New York: Viking. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-14-303667-8.

- ↑ Abrams, Ray (Summer 1940). "The Contribution of Sociology to a Course on Marriage and the Family". Living. 2 (3): 82–84. doi:10.2307/346602. JSTOR 346602.

- ↑ https://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/cps2004/tabA1-all.csv

- ↑ https://www.census.gov/cps/data/cpstablecreator.html

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey America's Families and Living Arrangements: 2006.

- ↑ Benokraitis, Nijole (2011). Marriages and Families. Upper Saddle River, Nj: Pearson Education Inc. pp. 76–100. ISBN 978-0-205-20403-8.

- ↑ Copen, C.E. et al. (2012). First Marriages in the United States: Data from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Hyattsville, Md.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

- ↑ "Income Data – State Median Income – U.S Census Bureau". Census.gov. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ Censky, Annalyn (September 13, 2011). "Poverty rate rises as incomes decline – Census – Sep. 13, 2011". Money.cnn.com. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- 1 2 Allison Linn, Today, October 26, 2013, Marriage as a 'luxury good': The class divide in who gets married and divorced, Accessed October 26, 2013

- ↑ "Types of Marriages".

- 1 2 Barbara Bradley Hagerty (May 27, 2008). "Some Muslims in U.S. Quietly Engage in Polygamy". National Public Radio: All Things Considered. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ↑ "10 Tax Benefits and Changes After Marriage | H&R Block". Tax Information Center. 2014-09-25. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "United States Wedding Traditions". Euroevents & Travel, LLC. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Oremus, Will (19 March 2015). "The Wedding Industry's Pricey Little Secret". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- 1 2 "Common-Law Marriage". National Conference of State Legislatures. April 19, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ↑ Lind, Göran (2008). Common law marriage: a legal institution for cohabitation. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 187–190. ISBN 978-0-19-536681-5.

- ↑ Shah, Dayna K. "Defense of Marriage Act: Update to Prior Report" (PDF). United States General Accounting Office. pp. 1–2. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ↑ "14 Supreme Court Cases: Marriage is a Fundamental Right". American Foundation for Equal Rights. July 19, 2012. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Board, The Editorial (2015-06-26). "Opinion | A Profound Ruling Delivers Justice on Gay Marriage". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ↑ in 2017, Connecticut and Texas became the 24th and 25th states to set a minimum age , and in 2018, Florida, Kentucky, Arizona, Delaware and Tennessee became the 26th, 27th, 28th, 29th and 30th state to set a minimum age

- ↑ "Understanding State Statutes on Minimum Marriage Age and Exceptions". Tahirih Justice Center. November 2016. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- ↑ More than 200,000 children married in US over the last 15 years

- ↑ https://legiscan.com/TN/bill/HB2134/2017

- ↑ Larson, Aaron (3 February 2017). "What is Common Law Marriage". ExpertLaw. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ↑ "Marriage Laws of the Fifty States, District of Columbia and Puerto Rico". Wex. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ↑ Gore, Leada (28 December 2016). "Common law marriage in Alabama ending Jan. 1, 2017". Alabama Media Group. Al.com. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ↑ See "United States v. Juillerat, ACM 206-06 (A.F.C.C.A. 2016)" (PDF). Court of Criminal Appeals. United States Airforce. Retrieved 11 September 2017. (A ceremonial marriage had been declared invalid by the state because it was not filed as required by law, but the marriage was treated as valid under military law such that the servicemember was convicted of bigamy.)

- ↑ See, e.g., "Declaration and Registration of Informal Marriage" (PDF). Texas Health and Human Services. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ↑ 9 GCA §31.10

- ↑ 33 L.P.R.A. § 4754

- ↑ West's Encyclopedia of American Law. Eds. Jeffrey Lehman and Shirelle Phelps. Vol. 8. 2nd ed. Detroit: Gale, 2005. 26–28. 13 vols. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Thomson Gale. Brigham Young University – Utah. 11 Dec. 2007

- ↑ "U.S. laws and Senate hearings on polygamy".

- ↑ Matter of Mujahid, 15 I. & N. Dec. 546 (BIA 1976)

- ↑ 8 USC §1182 (a)(10)(A)

- ↑ Loewy, Arnold H. (1975). "Criminal Law in a nutshell 2nd Ed". West Publishing Co.: 131.

- ↑ Woodruff's declaration was formally accepted in a church general conference on October 6, 1890.

- ↑ Philly's Black Muslims Increasingly turn to polygamy

- ↑ "Annulment".

- 1 2 "United States Citizenship and Immigration Services". Archived from the original on November 2, 2006. Retrieved November 11, 2011. Application form.

- ↑ "United States Citizenship and Immigration Services". Archived from the original on November 2, 2006. Retrieved November 11, 2011. , Laws.

- ↑ Legal Information Institute. "Improper entry by alien". Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ↑ "Assisting Immigrants of Domestic Violence". Retrieved November 11, 2011. , Immigration Services.

- ↑ "United States Citizenship and Immigration Services". Retrieved November 11, 2011. , Form I-864.

- 1 2 "The intersection of Family Law and Immigration Law: Alien love and marriage". Retrieved February 26, 2009. , Immigration Law.

- 1 2 Elson, Amy (Fall 1997). "The Mail-Order Bride Industry and Immigration:Combating Immigration Fraud". , Mail Order Bride.

- 1 2 Lawton, Zoë; Callister, Paul (March 2011). "'Mail-order brides': are we seeing this phenomenon in New Zealand?" (PDF). Institute of Policy Studies.

- ↑ US Department of Justice, "1948 Marriage Fraud—8 U.S.C. § 1325(c) and 18 U.S.C. § 1546", US Attorneys Manual, Title 9, Criminal Resource Manual.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Chang-Muy, Fernando (2009). Social Work with Immigrants and Refugees. Springer Publishing Company, LLC. Retrieved August 12, 2011. .

- 1 2 3 'Same-sex marriage and spousal visas,' http://www.usvisalawyers.co.uk/article23.

- ↑ https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/12pdf/12-307_6j37.pdf

- ↑ Brian K. Williams, Stacy C. Sawyer, Carl M. Wahlstrom, Marriages, Families & Intimate Relationships, 2005, Marriages, Families & Intimate Relationships.

- ↑ Thornton, Arland; William G. Axinn; Yu Xie (2007). Marriage and cohabitation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-226-79866-0. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ↑ "Why More Parents Are Choosing Cohabitation Over Marriage". June 22, 2012.

Further reading

- Culver Bernardo Alford, Jus civile matrimoniale in statibus foederatis americae septentrionalis cum jure canonico comparatum, Kenedy & Sons, 1938

- Dew, J.; Wilcox, B. (2011). "If momma aint happy, no one is". Journal of Marriage and Family. 73 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00782.x.

- Dethier, M.; Counerotte, C.; Blairy, S. (2011). "Marital satisfaction in couples with an alcoholic husband". Journal of Family Violence. 26 (2): 151–162. doi:10.1007/s10896-010-9355-z.

- Eby, Clare Virginia (2014). Until Choice Do Us Part: Marriage Reform in the Progressive Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Glorieux, I.; Minnen, J.; Tienoven, T. P. (2011). "Spouse "together time": Quality time within the household". Social Indicators Research. 101 (2): 281–287. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9648-x.

- Gordon, C.; Arnetter, R.; Smith, R. (2011). "Have you thanked your spouse today?: Felt and expressed gratitude among married couples". Personality and Individual Differences. 50 (3): 339–343. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.012.

- Helms, H.; Walls, J.; Crouter, A.; Susan, M. (2010). "Provider role attitudes, marital satisfaction, role overload, and housework: A dyadic approach". Journal of Family Psychology. 24 (5): 568–577. doi:10.1037/a0020637. PMC 2958678.

- Hernandez, K.; Mahoney, A.; Pargament, K. (2011). "Sanctification of sexuality: Implications for newlyweds' marital and sexual quality". Journal of Family Psychology. 25 (5): 775–780. doi:10.1037/a0025103.

- Medina, A.; Lederhos, C.; Lillis, T. (2009). "Sleep disruption and decline in marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood". Families, Systems, & Health. 27 (2): 153–160. doi:10.1037/a0015762.

- Meltzer, A.; McNulty, J.; Novak, S.; Butler, E.; Karney, B. (2011). "Marriages are more satisfying when wives are thinner than their husbands". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2: 416–424. doi:10.1177/1948550610395781.

- Rust, J.; Goldstein, J. (1989). "Humor in marital adjustment". Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. 2 (3): 217–223. doi:10.1515/humr.1989.2.3.217.

- Schudlich, T.; Mark, C.; Lauren, P. (2011). "Relations between spouses' depressive symptoms and marital conflict: A longitudinal investigation of the role of conflict resolution styles". Journal of Family Psychology. 25 (4): 531–540. doi:10.1037/a0024216. PMC 3156967.

- George Will (2016), Social inequality’s deepening roots, Dallas News

External links

- National Survey of Family Growth - federal statistics