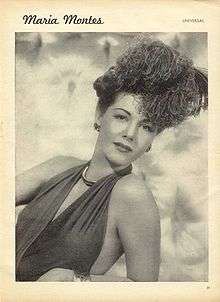

Maria Montez

| María Montez | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

María África Gracia Vidal 6 June 1912 Barahona, Dominican Republic |

| Died |

7 September 1951 (aged 39) Suresnes, France |

| Cause of death | Heart attack and drowning |

| Resting place | Cimetière du Montparnasse |

| Occupation | actress |

| Years active | 1940–1951 |

| Spouse(s) |

William McFeeters (m. 1932; div. 1939) |

| Children | Tina Aumont |

| Awards | Order of Merit of Juan Pablo Duarte (1943)[1] |

María África Gracia Vidal (6 June 1912 – 7 September 1951), known as The Queen of Technicolor, was a Dominican motion picture actress who gained fame and popularity in the 1940s as an exotic beauty starring in a series of filmed-in-Technicolor costume adventure films. Her screen image was that of a hot-blooded Latin seductress, dressed in fanciful costumes and sparkling jewels. She became so identified with these adventure epics that she became known as "The Queen of Technicolor". Over her career, Montez appeared in 26 films, 21 of which were made in North America and the last five were made in Europe.

Early life

Montez was born María Antonia García Vidal de Santo Silas (some sources cite María África Gracia Vidal or María África Antonia García Vidal de Santo Silas as her birth name) in Barahona, Dominican Republic.[2] She was one of ten children born to Ysidoro García, a Spaniard, and Teresa Vidal, a Dominican of colonial descent. Montez was educated at the Sacred Heart Convent in Santa Cruz de Tenerife. In the mid-1930s, her father was appointed to the Spanish consulship in Belfast, Northern Ireland where the family moved. It was there that Montez met her first husband, William G. McFeeters, whom she married at age 17.[1] In the book, Maria Montez, Su Vida[3] by Margarita Vicens de Morales, 2003 edition, on page 26, there is a copy of Montez's birth certificate proving that her original name was Maria Africa Gracia Vidal. Her father's name was Isidoro Gracia (not Garcia) and her mother's name was Teresa Vidal. On page 54, there is a copy of a fake biography made by Universal Pictures, where it says that Montez was educated in Tenerife and that she lived in Ireland, which was never true. Instead, it claims that Montez lived the first 27 years of her life in the Dominican Republic.

Career

Montez was spotted by a talent scout while visiting New York. Her first film was The Invisible Woman (1940). It was made for Universal Pictures, who signed her to a long term contract starting at $150 a week.[4]

She had small decorative roles in two films with the comedy team of Richard Arlen and Andy Devine, Lucky Devils and Raiders of the Desert; the Los Angeles Times said she "was attractive as the oasis charmer" in the latter.[5] She also appeared in Moonlight in Hawaii and Bombay Clipper. She had a small part in That Night in Rio (1941), made at 20th Century Fox.

Universal did not have a "glamour girl" like other studios - an equivalent to Hedy Lamarr (MGM), Dorothy Lamour (Paramount), Betty Grable (20th Century Fox), Rita Hayworth (Columbia) or Ann Sheridan (Warner Bros). They decided to groom Maria Montez to take this role and she received a lot of publicity.[6] Montez was also a keen self-promoter. In the words of The Los Angeles Times "she borrowed an old but sure-fire technique to get ahead in the movies. She acted like a movie star. She leaned on the vampish tradition set up by Nazimova and Theda Bara... She went in heavily for astrology. Her name became synonymous with exotic enchantresses in sheer harem pantaloons."[7] She took on a "star" pose in her private life. One newspaper called her "the best commissary actress in town... In the studio cafe, Maria puts on a real show. Always Maria makes an entrance."[4]

In June 1941 Montez's contract with Universal was renewed.[8] She graduated to leading parts with South of Tahiti, co-starring Brian Donlevy. She also replaced Peggy Moran in the title role of The Mystery of Marie Roget (1942).[9] Public response to South of Tahiti was enthusiastic enough for the studio to cast Montez in her first starring part, Arabian Nights. She claimed in 1942 she was making $250 a week.[6]

Arabian Nights and Stardom

Arabian Nights was a prestigious production for Universal, its first shot in three-strip Technicolor, produced by Walter Wanger and starring Montez, Jon Hall and Sabu. The resulting movie was a big hit and established Montez as a star.

Montez wanted to portray Cleopatra[10] but instead Universal reunited her with Hall and Sabu in White Savage (1943) (where Montez was upped from second-billing to top-billing). They made a third, Cobra Woman (1944). All the films were popular.

In 1943 Montez was awarded two medals from the Dominican government for her efforts in promoting friendly relations between the US and her native land.[11]

Universal wanted three more movies starring Montez, Hall and Sabu. However Sabu was drafted into the army and so was replaced by Turhan Bey in Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1944). Hall, Montez and Bey were meant to reunite in Gypsy Wildcat (1944), but Bey was required on another movie and ended up being replaced by Peter Coe. Sudan (1945) starred Montez, Hall and Bey - with Bey as Montez' romantic interest this time.

Flame of Stamboul was another proposed Hall-Bey-Montez film but it was postponed.[12] Universal also announced that Montez would play Elizabeth of Austria in The Golden Fleece, based on a story by Bertita Harding, but it was not made.[13] She did appear in Follow the Boys, Universal's all-star musical, and Bowery to Broadway.

In 1944 Montez said that the secret to her success was that she was "sexy but sweet... I am very easy to get along with. I am very nice. I have changed a lot during the last year. I have outgrown my old publicity. I used to say and do things to shock people. That was how I became famous. But now it is different. First the public likes you because you're spectacular. But after it thinks you are a star it wants you to be nice. Now I am a star, I am nice."[14]

Conflicts with Universal

Montez said she was "tired of being a fairy tale princess all the time" and wanted to learn to act.[14] She fought with Universal for different parts.

"Sudan is making more money than the others and Universal thinks on that account I should appear in more of these films," she said. "But I want to quit these films when they are at a peak, not on the downbeat. It isn't only that the pictures are all the same, but the stories are one just like the other."[15]

Montez went on suspension for refusing the lead in Frontier Gal; her role was taken by Yvonne De Carlo who had become a similar sort of star to Montez and began to supplant the latter's 's position at the studio.[16]

In 1946 Montez visited France with Aumont and both became excited about the prospect of making movies there. In particular, Aumont negotiated rights to the book Wicked City and Jean Cocteau wanted to make a film with both. Aumont says they were determined to get out of their respective contracts in Hollywood and move.[17]

Universal put Montez in a modern-day story, Tangier, an adaptation of Flame of Stamboul; it reunited her with Sabu, although not Jon Hall, who was in the army. There was some talk Montex would star in The Golden Fleece project (as Queen of Hearts), produced independently with Aumont co-starring.[18] The King Brothers reportedly offered her $150,000 plus 20% of the profits to appear in The Hunted.[19] Neither was made Instead Montez appeared in a Technicolor western for Universal, Pirates of Monterey (1947) with Rod Cameron.

In February 1947 she and Aumont started filming a fantasy adventure, Siren of Atlantis (1948) for a fee of 100,000;. In April she was borrowed by Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. to appear in the sepia-toned swashbuckler The Exile (1948), directed by Max Ophüls, produced by Fairbanks but released by Universal. Fairbanks Jr says Montez wanted to play the role over the objections of Universal; she later insisted on top billing despite the small nature of the role. In August 1947 Universal refused to pick up their option on Montez' services and she went freelance.[20] Montez sued Universal for $250,000 over the billing issue; the matter was settled out of court.[21]

Freelance career

In 1947 Hedda Hopper announced Montez and her husband would make The Red Feather about Jean Lafitte.[22] She was also announced for Queen of Hearts – this time not the Elizabeth of Austria project but an adaptation of a European play by Louis Verneuil, Cousin from Warsaw.[23] Neither film was made.

Siren of Atlantis ended up requiring re-shoots and was not released until 1948. It proved unsuccessful at the box office in the US (although it performed respectfully in Europe). Montez later successfully sued the producer for $38,000 in unpaid money.[24]

European career

Montez and Aumont formed their own production company, Christina Productions.[25] They moved to a home in Suresnes, Île-de-France in the western suburb of Paris under the French Fourth Republic. According to Aumont, they were going to star in Orpheus (1950) which Aumont says Jean Cocteau wrote for him and Montez. However the filmmaker decided to use other actors.[26]

Instead, in July 1948 Montez and Aumont made Wicked City (1949) for Christina Productions with Villiers directing and Aumont contributing to the script. It was one of the first US-French co productions after the war. Christina provided the services of Aumont, Montez and Lili Palmer; in exchange Christina's share would be paid off first out of US receipts.[27]

Aumont had begun writing plays and Montez appeared in a one-woman production, L'lle Heureuse ("The Happy Island"). Reviews were poor.[28] Her next film was Portrait of an Assassin (1949), which was meant to feature Orson Welles but ended up co-starring Arletty and Erich von Stroheim.

In September 1949 it was announced Montez would make The Queen of Sheba with Michael Redgrave for director Francois Villiers; however the film was not made.[29]

Montez appeared in an Italian swashbuckler, The Thief of Venice (1950), with a Hollywood director, John Brahm. Again in Italy she was in Love and Blood (1951), then there was a movie with her husband, Revenge of the Pirates (1951). It would be the last film she ever made.

Montez also wrote three books, two of which were published, as well as penning a number of poems.

At the time of her death, Montez's US agent Louis Shurr was planning her return to Hollywood in a film to be made for Fidelity Pictures, Last Year's Show.[7]

Personal life

Montez was married twice. Her first marriage was to William G. McFeeters, a wealthy banker who served in the British Army.[30] They married when Montez was 17 years old and later divorced.[1] Her second husband Jean-Pierre Aumont described him as "an Irishman who was naive enough to think he could lock her up in some frosty castle."[31] For over a year Montez was reportedly engaged to Claude Strickland, a flight officer with the RAF who she met in New York.[32] However it was later revealed that this was a publicity stunt.[33]

While working in Hollywood, Montez met French actor Jean-Pierre Aumont. Aumont later wrote "to say that between us it was love at first sight would be an understatement".[34] They married on 14 July 1943 at Montez's home in Beverly Hills. Charles Boyer was Aumont's best man and Jannine Crispin was Montez's matron of honour.[35] According to Aumont "it was a strange house. You didn't answer the phone or read the mail; the doors were always open. Diamonds were left around like ashtrays. Lives of the Saints lay between two issues of movie magazines. An astrologer, a physical culture expert, a priest, a Chinese cook, and two Hungarian masseurs were part of the furnishings. During her massage sessions, Montez granted audiences."[36]

Aumont had to leave a few days after wedding Montez to serve in the Free French Forces which were fighting against Nazi Germany in the European Theatre of World War II. At the end of World War II, the couple had a daughter, Maria Christina (also known as Tina Aumont), born in Hollywood on 14 February 1946.[1] In 1949 Aumont announced that they would get divorced but they remained together until Montez's death.[37]

Death

The 39-year-old Montez died in Suresnes, France on 7 September 1951 after apparently suffering a heart attack and drowning while taking a hot bath.[38][39] She was buried in the Cimetière du Montparnasse in Paris where her tombstone gives her amended year of birth (1918), not the actual year of birth (1912).

She left the bulk of her $200,000 estate to her husband and their five-year-old daughter.[40]

Legacy

In the Dominican Republic Montez received the decoration with the Order of Juan Pablo Duarte in the Grade of Officer and the Order of Trujillo in the same grade, which was given by the dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo in November, 1943. In 1944 she was named Goodwill Ambassador of Latin American countries to the United States in the so-called Good Neighbor policy.

Shortly after her death, a street in the city of Barahona, Montez's birthplace, was named in her honor.[38] In 1996, the city of Barahona opened the Aeropuerto Internacional María Montez (María Montez International Airport) in her honor. In 2012, a train station on Line 2 of the Santo Domingo Metro was named in her honor.

In 1976, Margarita Vicens de Morales published a series of articles in the Dominican newspaper Listín Diario's magazine Suplemento, where she presented the results of the her research on Montez's life. The research culminated in 1992 with the publication of the biography Maria Montez, Su Vida. After the first edition, a second edition was published in 1994 and a third in 2004.

In 1995, Montez was awarded the International Posthumous Cassandra, which was received by her daughter, Tina Aumont. In March 2012, the Casandra Awards were dedicated to Montez to commemorate the centenary of her birth.

The American underground filmmaker Jack Smith idolized Montez as an icon of camp style. He wrote an aesthetic manifesto titled "The Perfect Filmic Appositeness of Maria Montez", and made elaborate homages to her movies in his own films, including the notorious Flaming Creatures.[41]

The authors Terenci Moix and Antonio Perez Arnay wrote a book entitled Maria Montez, The Queen of Technicolor that recounted her life and reviewed her films.

The Dominican painter Angel Haché included in his collection Tribute to Film, a trilogy of Maria Montez and another Dominican painter, Adolfo Piantini, who dedicated a 1983 exhibit to the actress that included 26 paintings which were made in different techniques.

Dalia Davi, Puerto Rican actress from the Bronx, created the 2011 play The Queen of Technicolor Maria Montez. Davi wrote, directed, and starred in the play.[42]

The journalist and Dominican actress Celinés Toribio stars as Montez in the 2015 film Maria Montez: The Movie, which she also executive produced.

In 1998, the TV show Mysteries and Scandals[43] made an episode about Maria Montez.

Montez is mentioned by name in both the play (1968) and film (1970) versions of The Boys in the Band.

Filmography

- Boss of Bullion City (1940)

- The Invisible Woman (1940)

- Lucky Devils (1941)

- That Night in Rio (1941)

- Raiders of the Desert (1941)

- Moonlight in Hawaii (1941)

- South of Tahiti (1941)[44]

- Bombay Clipper (1942)

- The Mystery of Marie Roget (1942)

- Arabian Nights (1942)

- White Savage (1943)

- Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1944)

- Follow the Boys (1944)

- Cobra Woman (1944)

- Gypsy Wildcat (1944)

- Bowery to Broadway (1944)

- Sudan (1945)

- Tangier (1946)

- The Exile (1947)

- Pirates of Monterey (1947)

- Siren of Atlantis (1949)

- Wicked City (1949)

- Portrait of an Assassin (1949)

- Revenge of the Pirates (1951)

- The Thief of Venice (1951)

- Love and Blood/Shadows Over Naples (1951)

Unmade films

- Oh, Charlie! with Abbott and Costello (1941)[45]

References

- Aumont, Jean-Pierre (1977). Sun and Shadow: an Autobiography. W.W. Aumont.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Life and Times of Maria Montez". glamourgirlsofthesilverscreen.com.

- ↑ Hadley-García, George (1991). Hispanic Hollywood: The Latins in Motion Pictures. Carol Pub. Group. p. 114. ISBN 0-806-51185-0.

- ↑ http://www.mariamontez.org/mmsuvidaeng.html

- 1 2 Haugland, Vera (28 September 1941). "Maria Montez Puts On Best Show Without Benefit of Camera". The Washington Post. p. L2.

- ↑ "Pair Invade Film Desert". Los Angeles Times. 9 July 1941. p. 16.

- 1 2 "Maria Montez Puts Paprika in New Glamor Type: Sensational, but Proper, She Calls Herself". Chicago Daily Tribune. 15 November 1942. p. H10.

- 1 2 "Movie Colony Shocked by Maria Montez Death". Los Angeles Times. 8 Sep 1951. p. 3.

- ↑ "Maria Montez to Stay at Universal". The Washington Post. 28 June 1941. p. 8.

- ↑ "SCREEN NEWS HERE AND IN HOLLYWOOD: ' Teach Me to Live' Bought by Metro for Walter Pidgeon -- Fritz Lang Quits Film BIRTH OF THE BLUES' HERE Paramount Shows Comedy With Music -- 'Cadet Girl' Is New Attraction at Palace". New York Times. 10 December 1941. p. 35.

- ↑ Schallert, Edwin (21 December 1942). "DRAMA: Clio Role May Inspire Vivien Leigh Return Tierney Again Abroad Nile Queen Lures Maria Colman Termer on Tapis Cowan May Join U.A. Mary Philips Resumes". Los Angeles Times. p. 15.

- ↑ "Maria Montez Honored by Her Native Country". Los Angeles Times. 25 October 1943. p. 8.

- ↑ Scheuer, Philip K. (11 September 1943). "DRAMA AND FILM: Helen Walker Awarded Starring Opportunity Maria Montez, Hall and Turhan Bey Will Appear in 'Flame of Stamboul'". Los Angeles Times. p. 7.

- ↑ Schallert, Edwin (17 August 1943). "Likely to Pay Empress Role R.K.O. Halts Shooting on 'Revenge;' Alexander Knox in None Shall Escape'". Los Angeles Times. p. 10.

- 1 2 Mason, Jerry (12 March 1944). "AIR AND SULTRY: Maria Montez has changed in the last year--she says...". Los Angeles Times. p. F15.

- ↑ Schallert, Edwin (9 June 1945). "Daughter of Director Begins Cinema Career". Los Angeles Times. p. A5.

- ↑ "Screen News: To Aid Actors Fund". New York Times. 19 Apr 1945. p. 22.

- ↑ Aumont p 125-126

- ↑ Schallert, Edwin (22 May 1946). "Montez to Realize Aim in Austrian Ruler Role". Los Angeles Times. p. A2.

- ↑ Schallert, Edwin (20 April 1946). "Montez to Chameleon Way Out of Fantasy". Los Angeles Times. p. A5.

- ↑ Brady, Thomas F. (3 Aug 1947). "UNITED ARTISTS REMAINS DIVIDED: Pickford-Chaplin Impasse Blocks Reorganization -- Other Studio Notes". New York Times. p. X3.

- ↑ Brady, Thomas (4 Dec 1947). "FERRER MAY STAR IN FILM FOR GEIGER: Producer Plans to Do Movie of 'Moby Dick' and Stage Veteran Agrees to Role". New York Times. p. 41.

- ↑ Hopper, Hedda (30 June 1947). "Jean Aumont, Maria Montez Get Roles in 'Red Feather'". The Washington Post. p. 12.

- ↑ Hopper, Hedda (18 August 1947). "LOOKING AT HOLLYWOOD". Los Angeles Times. p. A3.

- ↑ "Maria Montez Files New Suit". Los Angeles Times. 14 October 1948. p. 5.

- ↑ Hopper, Hedda (28 March 1948). "Aumonts' Life Pivots on Baby: Jean Pierre and Maria Montez Have Dizzy Household Life Is Dizzy but Happy in Aumonts' Household". Los Angeles Times. p. C1.

- ↑ Aumont p 132

- ↑ Thomas Jr, George (12 December 1948). "Filming in Paris: Notes on First Franco -- American Projects". New York Times. p. X6.

- ↑ Aumont p 137

- ↑ Hopper, Hedda (20 September 1949). "Maria Montez Signs for 'Queen of Sheba'". Los Angeles Times. p. B6.

- ↑ Ruíz, Vicki; Sánchez Korrol, Virginia (2006). Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press. p. 485. ISBN 0-253-34681-9.

- ↑ Aumont p 81

- ↑ "Latin Actress Discloses Betrothal to R.A.F. Flyer: Maria Montez Tells Reason for Wearing British Insignia". Los Angeles Times. 18 June 1941. p. A8.

- ↑ "To the Rear of the Class, Baron Munchausen: Those Droll Fellows, the Press Agents, Set New Highs for the Lie Sublime". New York Times. 23 August 1942. p. X3.

- ↑ Aumont p 81

- ↑ "Maria Montez Weds French Actor". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 14, 1943. p. 5.

- ↑ Aumont p 81

- ↑ "DREAMS END: Actor Aumont to Divorce Maria Montez". Los Angeles Times. 23 March 1949. p. 24.

- 1 2 Ruíz, Vicki; Sánchez Korrol, Virginia. Latinas in the United States. Indiana University Press. pp. 486–487. ISBN 0-253-34680-0.

- ↑ The New York Times

- ↑ "Maria Montez Will Is Found". New York Times. 11 February 1952. p. 25.

- ↑ Senses of Cinema Archived 2009-02-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Dalia Davi's "Maria Montez Queen Of Technicolor"". repeatingislands.com. September 29, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ↑ Maria Montez - Mysteries and Scandals on YouTube

- ↑ Moreira, Renan (1941-11-21). "Maria Montez Visits Tech Campus; Regards Students 'As Typical College Men'". The Technique. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- ↑ Douglas MacLean Wins Film Producer Post: Gwenn to Act Diplomat Ross-Krasna Story Set Maria Montez Assigned 'Miss Arkansas' Sought Edwards in 'Power Dive' Schallert, Edwin. Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File) [Los Angeles, Calif] 23 Jan 1941: 13.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maria Montez. |

- Maria Montez on IMDb

- Maria Montez at AllMovie

- Maria Montez at Find a Grave

- A short montage on YouTube of clips of Montez, including her snake dance from Cobra Woman

- An appreciative essay comparing Maria Montez and her namesake, Warhol Superstar Mario Montez