The Boys in the Band

| The Boys in the Band | |

|---|---|

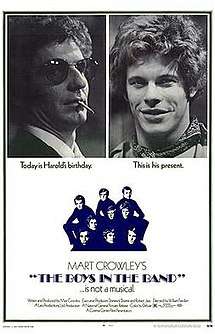

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | William Friedkin |

| Produced by |

Mart Crowley Kenneth Utt Dominick Dunne Robert Jiras |

| Screenplay by | Mart Crowley |

| Based on |

The Boys in the Band by Mart Crowley |

| Starring |

Kenneth Nelson Leonard Frey Cliff Gorman Laurence Luckinbill Frederick Combs Keith Prentice Robert La Tourneaux Reuben Greene Peter White |

| Cinematography | Arthur J. Ornitz |

| Edited by |

Gerald B. Greenberg Carl Lerner |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | National General Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 118 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.5 million |

| Box office | $3.5 million (US/Canada rentals)[1] |

The Boys in the Band is a 1970 American drama film directed by William Friedkin. The screenplay by Mart Crowley is based on his Off-Broadway play The Boys in the Band. It is among the first major American motion pictures to revolve around gay characters and is often cited as a milestone in the history of queer cinema, and is also thought to be the first mainstream American film to use the swear word cunt.

The ensemble cast, all of whom also played the roles in the play's initial stage run in New York City, includes Kenneth Nelson as Michael, Peter White as Alan, Leonard Frey as Harold, Cliff Gorman as Emory, Frederick Combs as Donald, Laurence Luckinbill as Hank, Keith Prentice as Larry, Robert La Tourneaux as Cowboy, and Reuben Greene as Bernard. Model/actress Maud Adams has a brief cameo appearance in the opening montage, as does restauranteur Elaine Kaufman.

Plot

The film is set in an Upper East Side apartment in New York City in 1968. Michael, a Roman Catholic sporadically-employed writer and a recovering alcoholic, is preparing to host a birthday party for one of his friends, Harold. Another friend, Donald, a self-described underachiever who has moved from the city, arrives and helps Michael prepare. Alan, Michael's (presumably straight) old college roommate from Georgetown, calls with an urgent need to see Michael. Michael reluctantly agrees and invites him to come over.

One by one, the guests arrive. Emory is a stereotypical flamboyant interior decorator. Hank, a soon-to-be-divorced schoolteacher, and Larry, a fashion photographer, are a couple but one with monogamy issues. Bernard is an amiable black bookstore clerk. Alan calls again to inform Michael that he will not be coming after all, and the party continues in a festive manner.

Unexpectedly, Alan has decided to drop by after all, and his arrival throws the gathering into turmoil.

"Cowboy," a hustler and Emory's "gift" to Harold, arrives. As tensions mount, Alan assaults Emory and in the ensuing chaos, Harold finally makes his grand appearance. In the middle of the scuffle, Michael impulsively begins drinking again. As the guests become more and more intoxicated, hidden resentments begin to surface, and the party moves indoors from the patio because of a sudden downpour.

Michael, who believes Alan is a closeted homosexual, begins a telephone game in which the objective is for each guest to call the one person he truly believes he has loved. With each call, past scars and present anxieties are revealed. Bernard reluctantly attempts to call the son of his mother's employer with whom he had had a sexual encounter as a teenager; Emory calls a dentist on whom he had had a crush while in high school. Bernard and Emory immediately regret the phone calls. Hank and Larry attempt to call each other, via two phone lines in Michael's apartment.

Michael's plan to "out" Alan with the game appears to backfire when Alan calls his wife, not the male college friend, Justin Stewart, whom Michael had presumed to be Alan's lover. As the party ends and the guests depart, Michael collapses into Donald's arms, sobbing. When he pulls himself together, it appears his life will remain very much the same.

Cast

- Kenneth Nelson as Michael

- Leonard Frey as Harold

- Cliff Gorman as Emory

- Laurence Luckinbill as Hank

- Frederick Combs as Donald

- Keith Prentice as Larry

- Robert La Tourneaux as Cowboy Tex

- Reuben Greene as Bernard

- Peter White as Alan McCarthy

- Maud Adams (uncredited) as photo model

- Elaine Kaufman (uncredited) as extra/pedestrian

Production

Mart Crowley and Dominick Dunne set up the film version of the play with Cinema Center Films, owned by CBS Television. Crowley was paid $250,000 plus a percentage of the profits for the film rights; in addition to this, he received a fee for writing the script.[2]

Crowley and Dunne originally wanted the play's director, Robert Moore, to direct the film but Gordon Stulberg, head of Cinema Center, was reluctant to entrust the job to someone who had never made a movie before. They decided on William Friedkin, who had just made a film of The Birthday Party by Harold Pinter that impressed them.[3]

Friedkin rehearsed for two weeks with the cast. He shot a scene that was offstage in the play where Hank and Larry kiss passionately; the actors who played them were reluctant to do this on film but eventually decided to. Friedkin then cut it in editing feeling it was over-sensationalistic; he says now he wishes he had kept it in.[3]

The bar scene in the opening was filmed at Julius in Greenwich Village.[4] Studio shots were at the Chelsea Studios in New York City.[5] According to commentary by Friedkin on the 2008 DVD release, Michael's apartment was inspired by the real-life Upper East Side apartment of actress Tammy Grimes. (Grimes was a personal friend of Mart Crowley.) Most of the patio scenes were filmed at Grimes' home. The actual apartment interior would not allow for filming, given its size and other technical factors, so a replica of Grimes' apartment was built on the Chelsea Studios sound stage, and that is where the interior scenes were filmed.

Songs featured in the film include "Anything Goes" performed by Harpers Bizarre during the opening credits, "Good Lovin' Ain't Easy to Come By" by Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, "Funky Broadway" by Wilson Pickett, "(Love Is Like A) Heat Wave" by Martha and the Vandellas, and an instrumental version of Burt Bacharach's "The Look of Love".

Reception

The film has a 94% approval rating on the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, based on 16 reviews with an average rating of 7.2/10.[6]

Critical reaction was, for the most part, cautiously favorable. Variety said it "drags" but thought it had "perverse interest." Time described it as a "humane, moving picture." The Los Angeles Times praised it as "unquestionably a milestone" but refused to run its ads. Among the major critics, Pauline Kael, who disliked Friedkin, was alone in finding absolutely nothing redeeming about it.[7]

Bill Weber from Slant Magazine wrote "The partygoers are caught in the tragedy of the pre-liberation closet, a more crippling and unforgiving one than the closets that remain."[8]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times observed, "Except for an inevitable monotony that comes from the use of so many close-ups in a confined space, Friedkin's direction is clean and direct, and, under the circumstances, effective. All of the performances are good, and that of Leonard Frey, as Harold, is much better than good. He's excellent without disturbing the ensemble... Crowley has a good, minor talent for comedy-of-insult, and for creating enough interest, by way of small character revelations, to maintain minimum suspense. There is something basically unpleasant, however, about a play that seems to have been created in an inspiration of love-hate and that finally does nothing more than exploit its (I assume) sincerely conceived stereotypes."[9]

In a San Francisco Chronicle review of a 1999 revival of the film, Edward Guthmann recalled, "By the time Boys was released in 1970 ... it had already earned among gays the stain of Uncle Tomism." He called it "a genuine period piece but one that still has the power to sting. In one sense it's aged surprisingly little — the language and physical gestures of camp are largely the same — but in the attitudes of its characters, and their self-lacerating vision of themselves, it belongs to another time. And that's a good thing."[10]

The film was perceived in different ways throughout the gay community. There were those who agreed with most critics and believed The Boys was making great strides while others thought it portrayed a group of gay men wallowing in self-pity.[11] There were even those who felt discouraged by some of the honesty in the production. One spectator wrote, "I was horrified by the depiction of the life that might befall me. I have very strong feelings about that play. It's done a lot of harm to gay people."[12][13]

While not as acclaimed or commercially successful as director Friedkin's later work, Friedkin considers this film to be one of his favorites. He remarked in an interview on the 2008 DVD for the movie, "It's one of the few films I've made that I can still watch."[3]

Awards and nominations

Kenneth Nelson was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for New Star of the Year - Actor. The Producers Guild of America Laurel Awards honored Cliff Gorman and Leonard Frey as Stars of Tomorrow.

Home media

The Boys in the Band was released by MGM/CBS Home Video on VHS videocassette in October 1980, and was later re-released on CBS/Fox Video. It was later released on laserdisc.

The DVD, overseen by Friedkin, was released by Paramount Home Entertainment on November 11, 2008. Additional material includes an audio commentary; interviews with director Friedkin, playwright/screenwriter Crowley, executive producer Dominick Dunne, writer Tony Kushner, and two of the surviving cast members, Peter White and Laurence Luckinbill; and a retrospective look at both the off Broadway 1968 play and 1970 film.

On June 16, 2015, it was released on blu-ray.

A 2011 documentary, Making the Boys, explores the production of the play and film in the context of its era.

See also

References

- ↑ "Big Rental Films of 1970". Variety. Penske Business Media. January 6, 1971. p. 11. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ↑ Cinema by, but Not Necessarily for, Television Warga, Wayne. Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File) [Los Angeles, Calif] July 28, 1968: c14.

- 1 2 3 Friedkin, William (2008). The Boys in the Band (Interview)

|format=requires|url=(help) (DVD). CBS Television Distribution. ASIN B001CQONPE. - ↑ Biederman, Marcia (June 11, 2000). "Journey to an Overlooked Past". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ↑ Alleman, Richard (February 1, 2005). "Union Square/Gramercy Park/Chelsea". The Movie Lover's Guide: The Ultimate Insider Tour of Movie New York. New York: Broadway Books. p. 231. ISBN 9780767916349.

- ↑ "Boys in the Band (1970)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ↑ "The Boys in the Band". New York. New York Media. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ↑ Ryll, Alexander. "Gay Essential Films to Watch, The Boys In The Band". Gay Essential. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (March 18, 1970). "Screen: 'Boys in the Band'". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ↑ Guthmann, Edward (January 15, 1999). "'70s Gay Film Has Low Esteem". The San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ↑ Klemm, Michael D. (November 2008). "The Boys are Back in Town". CinemaQueer. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (June 9, 1996). "THEATER;In a Revival, Echoes of a Gay War of Words". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ↑ Scheie, Timothy (2001). "The Boys in the Band, 30 Years Later". The Gay and Lesbian Review. 8 (1): 9. Retrieved July 17, 2018.