Marshall Taylor

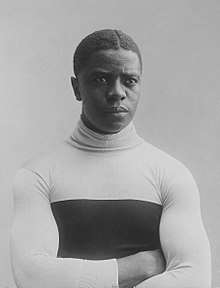

Taylor in July 1907 | ||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Marshall Walter Taylor | |||||||||||||

| Nickname | Major | |||||||||||||

| Born |

November 26, 1878 Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. | |||||||||||||

| Died |

June 21, 1932 (aged 53) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |||||||||||||

| Team information | ||||||||||||||

| Discipline | Track | |||||||||||||

| Role | Rider | |||||||||||||

| Rider type | Sprinter | |||||||||||||

| Amateur team(s) | ||||||||||||||

| 1895 | Albion Cycling Club | |||||||||||||

| Professional team(s) | ||||||||||||||

| 1896 | Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company | |||||||||||||

| 1899 | E. C. Stearns Bicycle Agency | |||||||||||||

| 1900 | Iver Johnson's Arms & Cycle Works | |||||||||||||

| Major wins | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Medal record

| ||||||||||||||

Marshall Walter "Major" Taylor (November 26, 1878 – June 21, 1932) was an American track cyclist who began his amateur career while he was still a teenager in Indianapolis, Indiana. He became a professional racer in 1896, at the age of 18, and won the sprint event at the 1899 world track championships in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, to become the first African American to achieve the level of world champion and the second black athlete to win a world championship in any sport. Taylor also set numerous world records in the sprint discipline in race distances ranging from the quarter-mile (0.4 km) to the two-mile (3.2 km). Taylor was an American sprint champion in 1899 and 1900, and completed races in the U.S., Europe and Australasia. He retired in 1910, at the age of 32, to his home in Worcester, Massachusetts.

In 1928, Taylor self-published his autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World, but severe financial difficulties forced him into poverty. He spent the final two years of his life in Chicago, Illinois, where he died in 1932. Throughout his athletic career Taylor challenged the racial prejudice he encountered on and off the velodrome and became a pioneering role model for other athletes facing racial discrimination. Taylor was inducted into the United States Bicycling Hall of Fame in 1989. Other tributes include memorials and historic markers in Indianapolis, Worcester, and at his gravesite in Chicago. Several cycling clubs, trails, and events in the U.S. have been named in his honor, as well as the Major Taylor Velodrome in Indianapolis and Major Taylor Boulevard in Worcester. Taylor has also been memorialized in a television mini-series and a song.

Early life and amateur career

Childhood and introduction to cycling

Marshall Walter Taylor was the son of Gilbert Taylor, a Civil War veteran, and Saphronia Kelter Taylor. His parents migrated from Louisville, Kentucky, and settled on a farm in Bucktown, a rural area on the western edge of Indianapolis, Indiana. Taylor, who was born on November 26, 1878, in Indianapolis was one of eight children in the family that included five girls and three boys. Around 1887, his father began working in Indianapolis as a coachman for the Southards, a wealthy white family.[1][2][3][4]

When Taylor was a child he occasionally accompanied his father to work. Taylor soon became a close friend of the Southards's son, Daniel,[4] who was the same age. From the age of eight until he was twelve, Taylor lived with the family and along with Daniel was tutored at their home. Taylor's living arrangement with the Southards provided him with more advantages than his parents could provide; however, this period of his life abruptly ended when the Southards moved to Chicago, Illinois.[5][6][7][8] Taylor, who remained in Indianapolis, returned to live at his parents' home and "was soon thrust into the real world."[4]

The Southards provided 12-year-old Taylor with his first bicycle. By 1891 or early 1892, he had become such an expert trick rider that Tom Hay, an Indianapolis bicycle shop owner, hired him to perform bicycle stunts in front of the Hay and Willits bicycle shop. Taylor earned $6 a week for cleaning the shop and performing the stunts, plus a free bicycle worth $35.[5][2][9] It is likely that Taylor received his nickname of "Major" because he performed the cycling stunts wearing a military uniform.[5][n 1]

Taylor left the Hay and Willits shop in 1892 or early 1893 to take a job as head trainer for Harry T. Hearsey's bicycle shop in Indianapolis, teaching local residents how to ride. About two years later, while working at Hearsey's shop, Taylor met Louis D. "Birdie" Munger, a former high-wheel bicycle racer who owned the Munger Cycle Manufacturing Company, a racing bicycle factory in Indianapolis. (Munger later established the Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company factory in Worcester, Massachusetts.) With a shared interest in bicycle racing, the two became friends and Munger hired the teenaged Taylor to work odd jobs that included sending Taylor to area high schools and colleges to train cyclists and promote Munger's line of racing bicycles.[11][12][13][14] Munger had also "made up his mind to make Taylor a champion" and coached him to become a racer.[15] While working for Munger, Taylor joined the See-Saw Cycling Club, an all-black cycling club in Indianapolis.[16][17]

Early years and East Coast move

Taylor began entering amateur bicycle races around 1892, while in his early teens, and continued until 1896, when he became a professional racer. Although he competed in road and track races during his amateur career, Taylor excelled in the track sprints, especially the one-mile (1.6 km) race.[18][19] Taylor won his first cycling race, a ten-mile (16 km) amateur event in Indianapolis in 1892.[20] He received a 50-minute handicap (head start) in the road race because of his young age. Taylor also traveled to Peoria, Illinois, to compete in another meet, winning third place in the under-16 age category.[21][19]

Taylor encountered racial prejudice throughout his racing career from some of his competitors. In addition, some local track owners feared that other cyclists would refuse to compete if Taylor was present for a bicycle race and banned him from their tracks.[22] In 1893, for example, after 15-year-old Taylor beat a one-mile amateur track record, he was "hooted" and then barred from the track.[15]

Major Taylor won his first significant cycling competition on June 30, 1895, when he was the only rider to finish a grueling 75-mile (121 km) road race near his hometown of Indianapolis. During the race Taylor received threats from his white competitors, who did not know that he had entered the event until the start of the race. A few days later, on July 4, 1895, Taylor won a ten-mile road race in Indianapolis that made him eligible to compete at the national championships for black racers in Chicago. Later that summer, he won the ten-mile championship race in Chicago by ten lengths and set a new record for black cyclists of 27:32.[23][22][24][25]

In 1895, Taylor and Munger relocated from Indianapolis to Worcester. At that time it was a center of the U.S. bicycle industry that included half a dozen factories and thirty bicycle shops. Munger, who was Taylor's employer, lifelong friend, and mentor, had decided to move his bicycle manufacturing business to the state of Massachusetts,[15][26] which was also a more tolerant area of the country.[27]

Munger and Charles Boyd, a business partner, established the Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company with factories in Worcester, and Middletown, Connecticut. For Taylor, who continued to work for Munger as a bicycle mechanic and messenger between the company's two factory locations,[15][28][29] the move to the East Coast offered "higher visibility, larger crowds, increased sponsorship dollars, and greater access to world-class cycling venues."[30] After Taylor's relocation to Massachusetts, he joined the all-black Albion Cycling Club in 1895 and trained at the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) in Worcester.[31][32] Taylor is first mentioned in The New York Times on September 26, 1895, as a competitor in the Citizen Handicap event, a ten-mile race on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn, New York. Taylor raced with a 1:30 handicap in a field of 200 competitors that included nine scratch riders.[33]

In 1896, Taylor entered numerous races in the Northeastern states of Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Connecticut. After winning a ten-mile road race in Worcester, Taylor competed in the 25-mile (40 km) Irvington–Millburn race in New Jersey, also known as the Derby of the East. Within half a mile (0.8 km) of the finish line, someone startled Taylor by tossing ice water into his face and he finished in 23rd place. Taylor's first major East Coast race was in a League of American Wheelmen (LAW) one-mile contest in New Haven, Connecticut, where he started in last place but won the event.[34][35] In August 1896, Taylor made a trip to Indianapolis, where he set an unofficial new track record of 2:11 1⁄5 for a distance of one mile at the Capital City velodrome, beating Walter Sanger's official track record of 2:19 2⁄5. (Taylor could not compete with Sanger, a professional racer, in a head-to-head contest because he was still an amateur.)[36][37][38][39] Taylor's final amateur race took place on November 26, 1896, in the 25-mile Tatum Handicap at Jamaica, New York. Taylor finished the race in 14th place.[40][41]

Professional career

1896: First races

.jpg)

Taylor turned professional in 1896, at the age of eighteen, and soon emerged as the "most formidable racer in America."[15] Taylor's first professional race took place in front of 5,000 spectators on December 5, 1896. He competed in a half-mile handicap event on an indoor track at New York City's Madison Square Garden II on the opening day of a multi-day event.[42][43] Although the main event was a six-day race from December 6–12, other contests in shorter distances were held on December 5 to entertain the crowd. These races included the half-mile handicap for professionals in which Taylor competed, a half-mile race between Jay Eaton and Teddy Goodman, and a half-mile scratch race. In addition, there were half-mile scratch and handicap races for amateurs.[44]

Taylor began the half-mile handicap race on December 5, with a 35-yard (32 m) advantage over the scratch racers. He beat a field of competitors that included Tom Cooper, Philadelphia's A. C. Meixwell, and scratch rider E. C. Bald, who represented New York's Syracuse, and rode a Barnes bicycle. Taylor won the race riding Munger's "Birdie Special" bicycle and beat Bald by 20 yards (18 m) in a sprint to the finish.[45][46][47]

From December 6–12, 1896, Taylor participated as one of 28 competitors in a six-day event at Madison Square Garden. Although Taylor had just become a professional, he had achieved enough notoriety, possibly because of his stunning win on December 5, to be listed among the "American contestants" that also included A. A. Hansen (the Minneapolis "rainmaker") and Teddy Goodman. In addition, many "experts from abroad" participated in the meet such as Switzerland's Albert Schock, Germany's Frank J. Waller, Frank Forster, and Ed von Hoeg, and Canada's B. W. Pierce. Several countries were represented in the event, including Scotland, Wales, France, England, and Denmark.[44][47]

As the fascination with six-day races spread across the Atlantic from its origins in the United Kingdom, their appeal to base instincts attracted large crowds. The more spectators who paid at the gate, the bigger the prizes, which provided riders with the incentive to stay awake–or be kept awake–in order to ride the greatest distance. To prepare for the event, Taylor went to Brooklyn, where he became a member of the South Brooklyn Wheelmen. An estimated crowd of 6,000 spectators attended the final day of the Madison Square Garden races in December 1896.[48][49] During these long, grueling races, riders suffered delusions and hallucinations, which may have been caused by exhaustion, lack of sleep, or perhaps use of drugs.[50][43][51][n 2]

Madison Square Garden's six-day event in 1896 was the longest race Taylor had ever entered. After Taylor refused to continue racing on the final day of the long-distance competition, exhausted from physical exertion and lack of sleep, a Bearnings reporter overheard him comment: "I cannot go on with safety, for there is a man chasing me around the ring with a knife in his hand."[53] Taylor completed a total of 1,732 miles (2,787 km) in 142 hours of racing to finish in eighth place.[54] Teddy Hale, the race winner, completed 1,910 miles (3,070 km) and took home $5,000 in prize money. Taylor never competed in any other six-day race.[55]

After Taylor's move to the East Coast in 1896, he initially lived in Worcester, where he worked for Munger, and in Middletown, the site of another of Munger's cycle factories.[33] Taylor also lived in other eastern cities, such as South Brooklyn, where he once trained,[44] but it is not known how long he still resided in New York after he became a professional racer.[56]

1897–1898: Fame and records

Taylor initially raced for Munger's Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. After the company went into receivership in 1897 he joined other racing teams.[58] Taylor competed in his first full year on the professional racing circuit in 1897.[59] Early in the season, at the Bostonian Cycle Club's "Blue Ribbon Meet" on May 19, 1897, Taylor rode a Comet bicycle to win first place in the one-mile open professional race.[60] On June 26, he won a quarters-mile (0.4 km) race at the track at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn. Taylor also beat Eddie Bald in a one-mile race in Reading, Pennsylvania, but finished fourth in the prestigious LAW convention in Philadelphia.[61][62][63]

As a professional racer Taylor continued to experience racial prejudice as a black cyclist in a white-dominated sport.[54] In November and December 1897, when the circuit extended to the racially-segregated South, local race promoters refused to let Taylor compete because he was black. Taylor returned to Massachusetts for the remainder of the season and Eddie Bald became the American sprint champion in 1897. Despite the obstacles, Taylor was determined to race.[64]

In the early years of his professional racing career, Taylor's reputation continued to increase as he competed in and won more races. Newspapers began referring to him as the "Worcester Whirlwind," the "Black Cyclone," the "Ebony Flyer," the "Colored Cyclone," and the "Black Zimmerman," among other nicknames. He also gained popularity among the spectators.[65][66][67] One of his biggest supporters was President Theodore Roosevelt who kept track of Taylor throughout his seventeen-year racing career.[15]

Early in the 1898 racing season Taylor beat Bald at Manhattan Beach, but lost to Eddie McDuffie at Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a 30-mile (48 km) paced race. On July 17 at Philadelphia, Taylor won his biggest victories of the season: first place in the one-mile championship and second place in the one-mile handicap races. On August 27, in a head-to-head race with Jimmy Michael of Wales, Taylor set a new world record of 1:41 2⁄5 for a one-mile paced match and beat the Welsh racer to the finish by 20 yards (18 m).[68][69]

Taylor was among several top cyclists who could claim the national championship in 1898; however, scoring variations and the formation of a new cycling league that year "clouded" his claim to the title.[15] Early in the year a group of professional racers that included Taylor had left the LAW to join a rival group, the American Racing Cyclists' Union (ARCU), and its professional racing group, the National Cycling Association (NCA). During the ARCU sprint championship in St. Louis and Cape Girardeau, Missouri, Taylor, who was a devout Baptist, refused to compete for religious reasons in the finals of the championship races because they were held on a Sunday. As a result of Taylor's decision not to race in the finals at Cape Girardeau, the ARCU suspended him from membership. Taylor petitioned the LAW for reinstatement in 1898 and was accepted, but Tom Butler, who had remained a LAW member after the break-up, was declared the League’s champion that year.[70][71][72][n 3]

During 1898–99, at the peak of his cycling career, Taylor established seven world records;[27][15] the quarter-mile, the one-third-mile (0.5 km), the half-mile, the two-thirds-mile (1.1 km), the three-quarters-mile (1.2 km), the one-mile, and the two-mile (3.2 km) distances. His one-mile world record of 1:41 from a standing start stood for 28 years.[54]

1899: World sprint champion

At the 1899 world championships in Montreal, Canada, Taylor won the one-mile sprint, to become the first African American to win a world championship in cycling. Taylor was the second black athlete, after Canadian bantamweight boxer George Dixon of Boston, to win a world championship in any sport.[27][39] Taylor won the one-mile world championship sprint in a close finish a few feet ahead of Frenchman Courbe d'Outrelon and American Tom Butler.[74][75] In addition, Taylor placed second in the two-mile championship sprint at Montreal behind Charles McCarthy and won the half-mile championship race.[15][76][77][78] Because the finals were held on Sundays, when Taylor refused to compete for religious reasons, he did not compete in another world championship contest until 1909 in Copenhagen, Denmark. Taylor lost in a preliminary heat at Copenhagen and did not compete in the finals.[79]

After Taylor's world championship win in 1899, many claimed that the event "had been a farce, because Taylor had not competed against the strongest riders."[80] World cycling's governing body, the International Cycling Association (replaced with the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) in 1900), did not allow NCA racers to compete at the world championships in Montreal. As a result, Taylor's accomplishments were somewhat diminished. Because the rival organizations (LAW and the NCA) would not recognize each other, two American champions were crowned in 1899. Tom Cooper was the NCA champion and Taylor was the LAW champion.[81][82]

In addition to the world championship wins in the one-mile and two-mile distances at Montreal and the LAW Championship, which he won on points, Taylor's victories in 1899 included twenty-two first-place finishes in major championship races around the U.S. Taylor's record-setting times were impossible to dismiss. No other rider had matched the "range and variety" of his winning performances, which made him an international celebrity.[15][83][80][84] In 1899, Taylor made several unsuccessful attempts to recapture his world record for a one-mile paced distance in two "strenuous record-breaking campaigns," before he finally achieved the new world record of 1:19 in November to regain the title of "the fastest man in the world."[85][86]

For the 1899 racing season, Taylor went to Syracuse and with Munger's assistance he signed a contract to race for the E. C. Stearns Company. Taylor, Munger, and Harry Sager, who was Taylor's bicycle parts sponsor, initially planned to negotiate a deal with the Olive Wheel Company; however, the men were able to work out a more lucrative contract with Stearns, who agreed to build Taylor's bicycles using a chainless gear mechanism that Sanger had designed. The bicycles only weighed about 20 pounds (9.1 kg) and had an 88-inch (2,200 mm) gear for sprinting and a 120-inch (3,000 mm) gear for longer, paced runs.[87][88] Stearns "also agreed to build Taylor a revolutionary steam-powered pacing tandem, behind which he could attack world records and challenge the leading exponents of paced racing."[89] Although the tandem was temperamental, it helped Taylor break Eddie McDuffie's one-mile world record on November 15, 1899, with a time of 1:19 at a speed of 45.56 mph (73.32 km/h).[90] In late 1899, Taylor signed a contract to race with the Iver Johnson's Arms & Cycle Works team of Fitchburg, Massachusetts, during the 1900 racing season.[91]

1900: American sprint champion

In 1900, when the LAW no longer governed professional bicycle races in the U.S., Taylor's future as a professional racer was in jeopardy. Fortunately, the ARCU and the NCA, who had banned Taylor from competing in their leagues, readmitted him after payment of a $500 fine.[85][92] Taylor won the American sprint championship on points in 1900. He also beat Tom Cooper, the 1899 NCA champion, in a head-to-head match in a one-mile race at Madison Square Garden in front of 50,000 to 60,000 spectators. In addition, Taylor set world records in the half-mile and two-thirds-mile sprints, and raced indoors using a "home trainer" in head-to-head competitions with other riders as a vaudeville act.[93][94][95] Taylor eventually settled in Worcester, where he purchased a home on Hobson Street in 1900.[56]

1901–1903: Europe and Australasia

Following his record-setting successes in the U.S. and Canada, Taylor agreed to a European tour. In 1901, Taylor made his first trip to Europe, but returned to compete in the U.S. after the conclusion of the European spring racing season. During his European tour Taylor still refused to race on Sundays, when most of the finals were held, because of his religious convictions.[96][97][98][99] It was reported that Taylor took a Bible with him when he traveled and began each race with a silent prayer because of his religious beliefs.[15]

Taylor was popular among the European race fans and news reporters: "Everywhere he went he was mobbed, talked about, or written up."[100] In 1901, Taylor won 42 of the 57 European races he entered.[101] A highlight of Taylor's European tour in 1901 were two match races with French champion Edmond Jacquelin at the Parc des Princes in Paris. Jacquelin won the first match by two lengths; Taylor won the second match by four lengths.[102]

Taylor also participated in a European tour in 1902, when he entered 57 races and won 40 of them to defeat the champions of Germany, England, and France.[15] In addition to racing in Europe, Taylor also competed in Australia and New Zealand in 1903 and 1904. In February 1903, for example, Taylor competed in the Sydney handicap for a $5,000 prize. A headline that flashed worldwide was "Rich Cycle Race."[103] During his world tour in 1903 Taylor earned prize money estimated at $35,000 ($923,352 in 2015 chained dollars).[101]

1907–1910: Later years

.jpg)

Following a collapse from the mental and physical strain of professional competition, Taylor took a two-and-a-half year hiatus from cycling between 1904 and 1906, before returning to race in France. He set two world records in Paris in 1907 for the half-mile standing start at 0:42 1⁄5 and the quarter-mile standing start at 0:25 2⁄5. Taylor also returned to Europe for the racing season in 1908 and in 1909. He finally broke his long-standing decision to avoid Sunday races in 1909 when he was nearing the end of his racing career. Taylor's last professional race took place on October 10, 1909, in Roanne, France, in a match race against French world champion Charles Dupré. Taylor won the race, but he did not return to Europe for the 1910 season and retired from competitive cycling.[104][105][106]

Taylor was still breaking records in 1908, but his age was starting to "creep up on him."[15] He retired from racing in 1910 at the age of 32. When Taylor returned to his home in Worcester at the end of his racing career, his estimated net worth was $75,000 ($1,978,611 in 2015 chained dollars) to $100,000 ($2,638,148 in 2015 chained dollars). Taylor won his final competition, an "old-timers race" among former professional racers, in New Jersey in September 1917.[107][108][109]

Racism in cycling

As Taylor gained notoriety as an amateur and a professional, he did not escape racial segregation. In 1894, the LAW changed its bylaws to exclude blacks from membership; however, it did permit them to compete in its races. Although Taylor's cycling was greatly celebrated abroad, particularly in France, his career was still restricted by racism, particularly in the Southern U.S., where some local promoters would not permit Taylor to compete against white cyclists.[110][111][112][113] Some restaurants and hotels also refused to serve him or provide him lodging.[5]

Taylor asserted in his autobiography that prominent bicycle racers of his era often cooperated to defeat him, such as the Butler brothers (Nat and Tom) were accused of doing in the one-mile world championship race at Montreal in 1899. At the LAW races in Boston, shortly after Taylor had won the world championship, he accused the entire field that included Tom Cooper and Eddie Bald, among others for fouling him.[114][115] Taylor complained after the event that he had been "bumped, jostled, and elbowed until I was sorely tried."[116][117][118] Racing promoter William A. Brady, who was also Taylor's manager, chastised the other riders for their "rough treatment" of Taylor during the race.[115]

While some of Taylor's fellow racers refused to compete with him, others resorted to intimidation, verbal insults, and threats to physically harm him.[5] While racing in Savannah, Georgia in the Winter of 1898, he received a written threat saying "Clear out if you value your life"; the previous day Taylor had challenged three riders together to a race after one of them had said they "didn't pace niggers."[119] Taylor recalled that ice water had been thrown at him during races and nails were scattered in front of his wheels. Taylor further stated in his autobiography that he had been elbowed and "pocketed" (boxed in) by other riders to prevent him from sprinting to the front of the pack, a tactic at which he was so successful.[120][121][117][118]

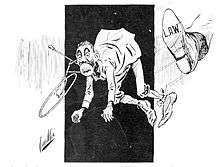

Taylor's competitors also tried to injure him. One incident occurred after the one-mile Massachusetts Open race at Taunton on September 23, 1897; at the conclusion of the race, William Becker, who placed third behind Taylor in second place, tackled Taylor on the race track and choked him into unconsciousness. Becker, who claimed that Taylor had crowded him during the race, was temporarily suspended while the incident was investigated. Becker received a $50 fine as punishment for his actions, but was reinstated and allowed to continue racing. In another incident, which occurred in February 1904, when Taylor was competing in Australia, he was seriously injured on the final turn of a race when fellow competitor Iver Lawson veered his bicycle toward Taylor and collided with his front wheel. Taylor crashed and lay unconscious on the track before he was taken to a local hospital and later made a full recovery. Lawson was suspended from racing anywhere in the world for a year as a result of his actions.[5][122][123]

Marshall Taylor[124]

Taylor explained that he included details of these incidents in his autobiography, along with his comments about his experiences, to serve as an inspiration for other African American athletes trying to overcome racial prejudice and discriminatory treatment in sports. Taylor cited exhaustion as well as the physical and mental strain caused by the racial prejudice he experienced on and off the track as his reasons for retiring from competitive cycling in 1910.[125][126] His advice to African American youths wishing to emulate him straightforward was that although bicycle racing had been the appropriate route to success for him, he would not recommend it in general. He suggested that individuals "practice clean living, fair play and good sportsmanship" and develop their best talent with a strong character, significant willpower, and "physical courage."[127] Despite many obstacles, Taylor rose to the top of his sport and became "one of the dominant athletes of his era."[20]

Retirement

After retiring from competition, Taylor applied to Worcester Polytechnic Institute to study engineering, despite the fact that he did not have a high school diploma, but he was denied admission and took up various business ventures.

Nearly twenty years after his retirement, Taylor wrote and self-published his autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy's Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds: An Autobiography (1928).[n 4] According to his book, Taylor was upbeat about his retirement: "I felt I had my day, and a wonderful day it was too." Taylor also claimed he had no regrets and "no animosity toward any man," but his autobiography included hints of bitterness in regard to his treatment as a competitor: "I always played the game fairly and tried my hardest, although I was not always given a square deal or anything like it."[129]

By 1930 Taylor had experienced severe financial difficulties from bad investments (including self-publishing his autobiography), the stock market crash, and businesses that proved unsuccessful. Taylor's home in Worcester and some of the family's personal property were sold to pay off debts. He also suffered from persistent ill health in his later years.[130][131][132]

Little is known of Taylor's life after the failure of his marriage and his move to Chicago around 1930. Taylor spent the final two years of his life in poverty, selling copies of his autobiography to earn a meagre income and residing at the YMCA Hotel in Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood.[133]

Death and legacy

In March 1932, Taylor suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized in the Cook County Hospital's charity ward, where he died on June 21, 1932, at age 53. The official cause of on his death certificate is "nephrosclerosis and hypertension," contributed by "Chronic myocarditis".[134] His wife and daughter, who survived him, did not immediately learn of his death and no one claimed his remains. He was initially buried at Mount Glenwood Cemetery in Thornton Township, Cook County, Illinois, (near Chicago) in an unmarked pauper's grave.[135] In 1948, a group of former professional bicycle racers used funds donated by Frank W. Schwinn, owner of the Schwinn Bicycle Co. at that time, to organize the exhumation and reburial of Taylor's remains in a more prominent location at the cemetery.[136][137] The plaque at the grave reads: "Dedicated to the memory of Marshall W. 'Major' Taylor, 1878–1932. World's champion bicycle racer who came up the hard way without hatred in his heart, an honest, courageous and god-fearing, clean-living, gentlemanly athlete. A credit to the race who always gave out his best. Gone but not forgotten.".[138]

Taylor's legacy lies in his willingness to challenge racial prejudice as an African American athlete in the white-dominated sport of cycling. He was also hailed as a sports hero in France and Australia. Taylor, who became a role model for other athletes facing racial prejudice and discrimination,[5] was "the first great black celebrity athlete" and a pioneer in his efforts to challenge segregation in sports. He also paved the way for others facing similar circumstances.[54] Taylor explained in his autobiography that he had no other African Americans to offer him advice and "therefore had to blaze my own trail."[127]

Honors and tributes

.jpg)

The Major Taylor Velodrome in Indianapolis was opened in July 1982 for the U.S. Olympic Festival.[139] Taylor was posthumously inducted into the United States Bicycling Hall of Fame in 1989.[140] In July 2006, Worcester renamed part of Worcester Center Boulevard, a high-traffic street, as Major Taylor Boulevard to honor his athletic feats as well as his character.[141] In April 2002, Taylor was one of the nine track cyclists inducted into the UCI Hall of Fame, created to commemorate 100 years of the Paris–Roubaix one-day road race and the inauguration of the World Cycling Centre.[142] In May 2008, the Major Taylor Association commissioned Antonio Tobias Mendez to create a sculpture to honor Taylor. The monument is installed in front of the Worcester Public Library in Worcester, Massachusetts.[27][143] In 2009, the Indiana Historical Bureau, Central Indiana Bicycling Association Foundation, and the Indiana State Fair Commission installed a state historical marker as a tribute to Taylor near the Indiana State Fairgrounds in Indianapolis. The marker is located at the intersection of Thirty-Eighth Street and the Monon Trail, close to the site where he had set an unofficial track record in 1896.[39]

A bike path in Chicago is named in Taylor's honor.[144] In September 2010, Columbus, Ohio, renamed its Alum Creek Trail bike path the Major Taylor Bikeway.[145][146][147] The first of the many cycling clubs named in Taylor's honor was organized in Columbus, in 1979.[148][149] In 2002, a group of African American students at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana, named their Little 500 team in Taylor's honor.[26] In 2009, the Cascade Bicycle Club community organization of Washington launched The Major Taylor Project, a youth cycling program.[150]

In popular culture

Actor Philip Morris portrayed Taylor in the 1992 television mini-series Tracks of Glory.[151] Blues musician Otis Taylor (no relation) recorded "He Never Raced on Sunday," a song about Taylor for his 2004 album Double V.[152] In 2007, Nike produced the Major Taylor "premium" collection of their most iconic sneakers in a light brown/neon yellow/white colorway.[153] SOMA Fabrications makes a set of bicycle handlebars called the Major Taylor Bar, which is a replica of 1930s drop handlebar that was named for Taylor.[154] Dewshane Williams portrayed Taylor in the Murdoch Mysteries episode, Tour de Murdoch.[155]

Marriage and family

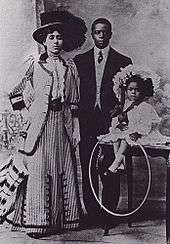

Taylor married Daisy Victoria Morris in Ansonia, Connecticut, on March 21, 1902. Morris was born on January 28, 1876, in Hudson, New York. Taylor met her around 1900 when she was living in Worcester, with her aunt and uncle.[156][157][158][159][160][135]

While in Australia in 1904, Taylor and his wife had their only child, a daughter that they named Rita Sydney in honor of Sydney, where she was born on May 11.[161][162] When Taylor, his wife, and daughter were not traveling, they lived in a large home on Hobson Avenue in Worcester that Taylor had purchased in 1900.[56]

After his retirement from racing in 1910 and the failure of subsequent business ventures in the 1920s, Taylor and his wife became estranged. She left him in 1930 and moved to New York City. Around the same time Taylor left Worcester and moved to Chicago; he never saw his wife or daughter again.[163]

Taylor's daughter, who graduated from the Sargent School of Physical Culture in Boston in 1925 and the University of Chicago in 1936, taught physical education at Virginia State University. She died in 2005 at age 101; her survivors include a son, Dallas C. Brown Jr., and his five children.[101][164] In 1984, Taylor's daughter donated an extensive scrapbook collection on her father to the University of Pittsburgh Archives.[165]

See also

Notes and references

Footnotes

- ↑ Andrew Ritchie, one of Taylor's biographers, offers other potential explanations for Taylor's nickname, but his military uniform appears to be the most likely reason, although Taylor never confirmed it. See [10]19.

- ↑ The extent of drug use during the era in which Taylor raced is "uncertain," but it was "not uncommon." At that time, many narcotics and pharmaceutical drugs, including opium, laudanum, morphine, heroine, and cocaine, among others, could be obtained legally.[52] Their exhaustion was countered by soigneurs (French: carers), helpers akin to seconds in boxing. Nitroglycerine, a drug used to stimulate the heart after cardiac attacks and was credited with improving riders' breathing, was also among the treatments supplied to riders.[50]

- ↑ Earl Kiser, nicknamed the "Little Dayton Demon," raced for the Stearns "Yellow Fellow" team during the same era as Taylor. Kiser became a two-time world cycling champion and competed all across Europe in the late 1890s. After Taylor was barred from racing, Kiser petitioned the ARCU to have him included.[73]

- ↑ The original version of Taylor's autobiography, printed by The Commonwealth Press in Worcester, Massachusetts, has a copyright date of 1928; however, other sources indicate that it was not published until 1929.[128][39]

- ↑ Thomas Gascoyne was a dual world-recordholder from England who defeated Taylor twice in one day at Boston on July 20, 1901.[166]

References

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 4.

- 1 2 Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 "Who was Major Taylor". Bridgewater State University. November 17, 2004. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Heyman, Brian (2010). Stories of African American Achievement (PDF). Bureau of International Information Programs. pp. 16–19. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 10.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 15.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 18.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 37.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 21–23.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "They had a Dream". Chronicle-Telegram. Elyria, Ohio. March 8, 1970.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 34.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 43.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 17–18.

- 1 2 Ritchie 1988, p. 31.

- 1 2 Ogden, Dale (Winter 1999). "Beginnings: The Ebony Streak". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. 11 (1): 28.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 9–10.

- 1 2 Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 34–36.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 43–45.

- 1 2 Moore, Wilma L. (Fall 2012). "Everyday People: Sports Champions and History Makers". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. 24 (4): 29.

- 1 2 3 4 "Recalling a Champ: Cyclist Major Taylor". SouthtownStar. Tinley Park, Illinois. October 18, 2009.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Gant & Hoffman 2013, p. 51.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 61–63.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 52.

- 1 2 "Pedalers Ready to Race". The New York Times. September 26, 1895.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 54–56.

- ↑ Gant & Hoffman 2013, p. 53.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 4 "Marshall "Major" Taylor". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 80.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 86.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 86–88.

- 1 2 Ritchie 1988, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 "Six Day Cycle Race". The Fort Wayne News. Fort Wayne, Indiana. December 5, 1896.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 85–88.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 62.

- 1 2 "Severe Spills — Defective Banking at Madison Square Garden Throws Many Riders". Syracuse Daily Standard. Syracuse, New York. December 6, 1896.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 60.

- 1 2 Novich 1964.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 65.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 45.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 Southwick, Albert B. (September 16, 2001). "Who was Major Taylor?". Telegram & Gazette. Worcester, Massachusetts.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 67–68.

- 1 2 3 Ritchie 1988, p. 138.

- ↑ O'Connor, Brion (February 25, 2015). "Honoring Major Taylor, America's first black world champion in any sport". Sports Illustrated. Time Inc. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 74.

- ↑ "Again Winners! Newton Tires". Boston Daily Globe. May 23, 1897.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 100.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 71.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 81.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 95.

- ↑ Gant & Hoffman 2013, p. 50.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 73.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 139.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 95.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 142.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Archdeacon, Tom (June 22, 2011). "Archdeacon: Cemetery brings sporting past to life". Dayton Daily News. Cox Ohio Publishing. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 165.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 168.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 166.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 127–129.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 128.

- 1 2 Ritchie 1988, p. 133.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 167.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 131.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 135.

- 1 2 Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 173–175.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 134.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 169.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 114.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 181.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 142.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 189.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 193.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 199.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 203.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 207.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 254.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 210.

- 1 2 3 Ogden, Dale (Winter 1898). "Thunderbolt, The Ebony Streak, The Blond Terror of Terre Haute". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. 1 (1): 42.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 181–82.

- ↑ "Rich Cycle Race". The Lowell Sun. Lowell, Massachusetts. August 6, 1904.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 297.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 303–308.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 315–316.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 306.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 311.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 321.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 115.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 37.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 41.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 125.

- 1 2 Ritchie 1988, p. 129.

- ↑ Taylor 1928, p. 37.

- 1 2 Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 106–107.

- 1 2 Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Della Valle 2009, pp. 214–215.

- ↑ Taylor 1928, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Taylor 1928, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 88–92.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Taylor 1928, p. 422.

- ↑ Taylor 1928, p. Forward.

- ↑ Taylor 1928, p. 420.

- 1 2 Taylor 1928, p. 427.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 239–243.

- ↑ Taylor 1928, pp. 421–422.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, pp. 320–322.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 221–225.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, p. 235.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 335.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 252–253.

- 1 2 Ritchie 1988, p. 255.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 256–257.

- ↑ Brill 2008, p. 95.

- ↑ "Grave marker of Marshall "Major" Taylor". Panoramio. Mountain View, California: Google. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ↑ Gray 2003, p. 188.

- ↑ "Marshall 'Major' Taylor". United States Bicycling Hall of Fame. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ Peter Schworm, Peter (July 24, 2006). "A black athlete changed the gears of cycling's world". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ↑ "Paris-Roubaix 100 Years Old and the UCI's WCC Inauguration in Aigle". UCI. April 14, 2002. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ↑ "Major Taylor Statue Dedication". Major Taylor Association Inc. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Major Taylor Bike Trail". Chicago Park District. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Alum Creek Trail renaming ded". FranklinCountyEvents.com. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ↑ Stephens, Jeff (August 30, 2010). "Columbus Trail to be dedicated to Major Taylor". Consider Biking. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ↑ "The Alum Creek Greenway Trail". The Central Ohio Greenway trail system. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ↑ "Major Taylor Cycling Club". Long Street Tour. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Other Major Taylor Clubs". Major Taylor Cycling Club of New Jersey. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ↑ "Teens from the Major Taylor Project will bicycle 200 miles on July 9 and 10 from Seattle to Portland". West Seattle Herald. Robinson Communications, Inc. July 1, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ↑ "Tracks of Glory (TV mini-series)". IMDb. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ↑ "Otis Taylor". Chicago Tribune. Tronc. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ Dalloni 2013, chpt. 75.

- ↑ "Major Taylor Bar". SOMA Fabrications. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Murdoch Mysteries Season 7 Episode 2". Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 178.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 180.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 253.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 338.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 191–192.

- ↑ "Wheel Notes". The Mansfield News. Mansfield, Ohio. August 6, 1904.

- ↑ Ritchie 1988, pp. 201–202.

- ↑ Kerber & Kerber 2014, p. 328.

- ↑ Brill 2008, p. 92.

- ↑ Marshall W. "Major" Taylor Scrapbooks, 1897-1904, AIS.1984.07. Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh.

- ↑ See Library of Congress, "U.S. Newspaper Directory 1690–Present" for: "Cycling: Leading Professionals Sidetrack Vailsburg––Gasgoyne's First Defeat in Pursuit Race". New-York Tribune. July 22, 1901. p. 8. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

Bibliography

- Brill, Marlene T. (2008). Marshall "Major" Taylor: World Champion Bicyclist, 1899–1901. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-6610-6.

- Campbell, Ballard C. (2008). Disasters, Accidents, and Crises in American History: A Reference Guide to the Nation's Most Catastrophic Events. New York City: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-3012-5.

- Dalloni, Michel (2013). Le Vélo. 100 Questions sur (in French). Brussels: La Boétie. ISBN 978-2-368-65006-6.

- Della Valle, Paul (2009). Massachusetts Troublemakers: Rebels, Reformers, and Radicals from the Bay State. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7627-5795-4.

- Gant, Jesse J.; Hoffman, Nicholas J. (Autumn 2013). "Wheel Fever". Wisconsin Magazine of History. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Gray, Ralph D. (2003). IUPUI—the Making of an Urban University. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34242-3.

- Kerber, Conrad; Kerber, Terry (2014). Major Taylor: The Inspiring Story of a Black Cyclist and the Men Who Helped Him Achieve Worldwide Fame. New York City: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62873-661-8.

- Novich, Max M. (1964). Abbotempo. United Kingdom: Abbott Universal.

- Ritchie, Andrew (1988). Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer. Mill Valley, California: Bicycle Books. ISBN 0-8018-5303-6.

- Taylor, Marshall (1928). The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy's Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds: An Autobiography. Worcester, Massachusetts: Wormley Publishing Company. OCLC 1989465.

Further reading

- Balf, Todd (2008). Major: A Black Athlete, a White Era, and the Fight to Be the World's Fastest Human Being. New York City: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-23658-6.

- Cline-Ransome, Lesa; Ransome, James (2003). Major Taylor, Champion Cyclist. New York City: Atheneum Books. ISBN 978-0-689-83159-1.

- Fitzpatrick, Jim (2011). Major Taylor in Australia. Kilcoy, Australia: Star Hill Studio. ISBN 978-0-9807480-2-4.

- Grivell, H. (Curly) (n.d.). Highlights from the life of Major Taylor. Australia: Sport Radio Press.

- Wilds, Mary (2002). A Forgotten Champion: The Story of Major Taylor, Fastest Bicycle Racer in the World. Avisson Young Adult Series. Greensboro, NC: Avisson Press. ISBN 978-1-888105-52-0.

- Whimpress, Bernard (2005). 'Major' Taylor at Adelaide Oval. Adelaide, Australia: Bernard Whimpress. ISBN 978-0-9750491-2-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Major Taylor. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |