Macrotermitinae

| Macrotermitinae | |

|---|---|

| |

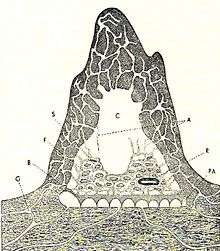

| Structure of a Macrotermes natalensis mound | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Clade: | Euarthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Blattodea |

| Family: | Termitidae |

| Subfamily: | Macrotermitinae Kemner, 1934 |

| Genera | |

|

14, see text | |

The Macrotermitinae, the fungus-growing termites, constitute a subfamily of the family Termitidae. The termites are traditionally classified as order Isoptera, but have been found to be a subgroup of the Blattodea (roaches and allies) and consequently should be treated as part of this group; what taxonomy entomologists eventually will settle upon has not been decided yet.

This subfamily consists of 14 genera and about 350 species and are distinguished by the fact that they cultivate fungi inside their nests to feed the members of the colony.

Colony

In Macrotermitinae, as in most other termites, the colony consists of a male and a female primary reproductive, the king and queen, secondary reproductives, workers and soldiers. The workers have gonads reduced in size and are sterile; in some species there are two sizes of worker, the larger ones being male and the smaller ones female. The soldiers, which have large heads and are specialised to defend the nest, are female.[1]

Distribution

The Macrotermitinae subfamily has a widespread distribution through the tropics of Africa, the Middle East, and southern and southeastern Asia, but it is not present in Australia or the New World.[2] Fossil evidence from Tanzania show that the Macrotermitinae developed agriculture about 31 million years ago.[3]

Ecology

Like other termites, Macrotermitinae are soil engineers, mixing their salivary secretions with soil particles to make their strong, hard mounds and galleries.[4] Their mounds are some of the largest built by any species of termite, with volumes of thousands of litres and lasting for many decades. They are probably the most complex mound colonies of any insect group.[5] There are 11 accepted genera in the Macrotermitinae and about 330 species, with the greatest diversity being in Africa. About 40 species of Termitomyces have been identified as symbionts. In contrast to the fungus-growing ants in the tribe Attini, the Termitomyces often bear fruiting bodies which produce spores, and it is believed that transmission of the fungus to other termites is mainly by horizontal transmission (sibling to sibling) rather than by vertical transmission (mother to daughter). Some species are an exception to this, and in all five species of the genus Microtermes tested, the symbiont fungi did not bear sexual fruiting bodies, and transmission was through the maternal route. Another exception was the single species Macrotermes bellicosus where again the fungus did not fruit, and where transmission was paternal.[5]

They have a rather rigid caste system, with little flexibility after the early instar stage. They also exhibit complex behavioural activities and their presence in an arid or semi-arid area can be dominant over other termite species. As compared to other higher termites however, they show some primitive features and have failed to evolve soil consumption.[4]

The mound contains galleries and chambers in which the termites grow fungi as endosymbionts. The fungi concerned are species of Termitomyces; it is unclear whether one species of termite is always associated with one species of fungus, and it is probable that several species of termite may utilise a single fungal species. The worker termites bring plant material such as dried grass, decaying wood and leaf litter, back to the mound. This material is chewed up and semi-digested by the termites, fertilised with their faeces and placed in the chambers where it is quickly colonised by the fungus to form a "fungus comb". The termites cultivate these fungus gardens, adding more substrate as required, and removing the older parts of the comb for consumption by all members of the colony.[5]

In addition, some species feed on various types of living and dead plant material including wood, but not on decomposing vegetation;[6] these termites have a similar microbial gut flora to other species of termite.[2]

Genera

|

|

Gallery

A Macrotermitinae mound in the Okavango Delta just outside Maun, Botswana

A Macrotermitinae mound in the Okavango Delta just outside Maun, Botswana A termite soldier (Macrotermitinae) in the Okavango Delta

A termite soldier (Macrotermitinae) in the Okavango Delta An ant of the genus Megaponera with a captured worker termite (Macrotermitinae) in the Okavango Delta, Botswana

An ant of the genus Megaponera with a captured worker termite (Macrotermitinae) in the Okavango Delta, Botswana Worker termites (Macrotermitinae) closing a newly exposed shaft inside a termite mound to prevent the entry of predators

Worker termites (Macrotermitinae) closing a newly exposed shaft inside a termite mound to prevent the entry of predators

References

- ↑ Sani, Imran Ali; Ahmed, Shahjahan Shabbir. Arthropodes & Classification of class Insecta. Lulu.com. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-312-80075-5.

- 1 2 Seckbach, Joseph (11 April 2006). Symbiosis: Mechanisms and Model Systems. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 736–745. ISBN 978-0-306-48173-4.

- ↑ Roberts, E.M.; Todd, C.N.; Aanen, D.K.; Nobre, T.; Hilbert-Wolf, H.L.; O'Connor, P.M.; Tapanila, L.; Mtelela, C.; Stevens, N.J. (2016). "Oligocene termite nests with in situ fungus gardens from the Rukwa Rift Basin, Tanzania, support a paleogene African origin for insect agriculture". PLoS ONE. 11 (6): e0156847. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156847. PMC 4917219. PMID 27333288.

- 1 2 König, Helmut (2006). Intestinal Microorganisms of Termites and Other Invertebrates. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 202. ISBN 978-3-540-28180-1.

- 1 2 3 Aanen, Duur K.; Eggleton, Paul; Rouland-Lefèvre, Corinne; Guldberg-Frøslev, Tobias; Rosendahl, Søren; Boomsma, Jacobus J. (2002). "The evolution of fungus-growing termites and their mutualistic fungal symbionts". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (23): 14887–14892. doi:10.1073/pnas.222313099. PMC 137514.

- ↑ Brian, Michael Vaughan (1978). Production Ecology of Ants and Termites. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-521-21519-0.

| Wikispecies has information related to Macrotermitinae |