Macartney–MacDonald Line

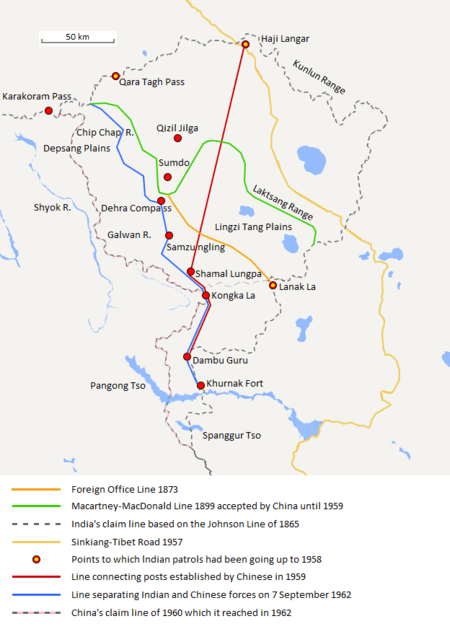

The Macartney–MacDonald Line is a proposed boundary in the disputed area of Aksai Chin. It was proposed by British Indian Government to China in 1899 via its envoy to China, Sir Claude MacDonald. The Chinese Government never gave any response to the proposal. Subsequently, the British Indian Government is said to have reverted to its traditional boundary, the Johnson Line.[1]

History

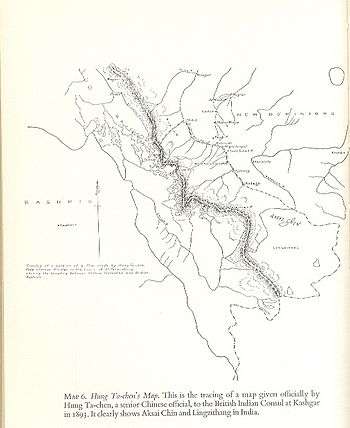

William Johnson, a civil servant with the Survey of India proposed the "Johnson Line" in 1865, which put Aksai Chin in Kashmir. This was accepted by China until 1893, when Hung Ta-chen, a senior Chinese official at St. Petersburg,[lower-alpha 1] gave maps of the region to George Macartney, the British consul at Kashgar, which coincided with it in broad details.[3]

However, by 1896, China showed interest in Aksai Chin, reportedly with Russian instigation.[4] As part of The Great Game between Britain and Russia, Britain decided on a revised boundary ceding underpopulated border territory to be "filled out" by China. It was initially suggested by Macartney in Kashgar and developed by the Governor General of India Lord Elgin. The new boundary placed the Lingzi Tang plains, which are south of the Laktsang range, in India, and Aksai Chin proper, which is north of the Laktsang range, in China.[5] The British presented this line, currently called the Macartney–MacDonald line, to the Chinese in a note by Sir Claude MacDonald, the British envoy in Peking.[5] The Qing government did not respond to the note. Scholars Fisher, Rose and Huttenback comment:

This proposed border agreement would have entailed major territorial concessions by the British, since the Government of India had demonstrated both on maps and through the exercise of authority in the Aksai Chin that they considered the Kunlun range to be the de facto boundary between Sinkiang and Kashmir. Indeed, most of the territory currently in dispute between New Delhi and Peking would have been conceded to China under this settlement. The Chinese Communists must indeed find it galling that the Ch'ing Court did not even formally reply to the British offer, thus rejecting it by default.[6]

The Macartney–MacDonald Line is a partial basis of the Sino-Pakistan Agreement. It has been suggested that a solution to the Sino-Indian border dispute could also be based on the Macartney–MacDonald Line.[7][8]

Description

The Macartney–MacDonald line is described as follows:

"From the Karakoram Pass the crests of the range run nearly east for about half a degree, and then turn south to a little below the 35th parallel.. Rounding... the source of the Karakash, the line of hills to be followed runs north-east to a point east of Kizil Jilga and from there, in a south-easterly direction, follows the Lak Tsung (Lokzhung) Range until that meets a spur.. which has hitherto been shown on our maps as the eastern boundary of Ladakh."[5]

Notes

- ↑ Mehra, An "agreed" frontier 1992, p. 103: "Huang Tachin (also Hung Chun or Hung Tajen) was a Chinese diplomat accredited to Russia as well as Germany, Austria-Hungary and Holland in 1887-90. During these years he rendered into Chinese a series of thirty-five maps, relating for the most part to the Sino-Russian borders."

References

- ↑ Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis 1990, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers 1970, pp. 73, 78.

- ↑ Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers 1970, pp. 73, 78: "Clarke added that a Chinese map drawn by Hung Ta-chen, Minister in St. Petersburg, confirmed the Johnson alignment showing West Aksai Chin as within British (Kashmir) territory."

- ↑ Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground 1963, pp. 68–69.

- 1 2 3 Calvin, James Barnard (April 1984). "The China-India Border War". Marine Corps Command and Staff College. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ↑ Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground 1963, p. 69.

- ↑ Verma, Colonel Virendra Sahai. "Sino-Indian Border Dispute At Aksai Chin - A Middle Path For Resolution" (PDF). Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ↑ "China was the Aggrieved; India, Aggressor in '62", Kai Friese interview Neville Maxwell, Outlook, 22 October 2012.

Bibliography

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via Questia, (Subscription required (help))

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Mehra, Parshotam (1992), An "agreed" frontier: Ladakh and India's northernmost borders, 1846-1947, Oxford University Press

- Woodman, Dorothy (1970) [first published 1969 by Barrie & Rockliff, The Cresset Press], Himalayan Frontiers: A Political Review of British, Chinese, Indian, and Russian Rivalries, Praeger

Further reading

- Noorani, A.G. (2010), India–China Boundary Problem 1846–1947: History and Diplomacy, Oxford University Press India, ISBN 978-0-19-908839-3