Luni, Italy

| Luni | |

|---|---|

| Comune | |

| Comune di Luni | |

|

View of Luni Mare with Ortonovo and Nicola in the background. | |

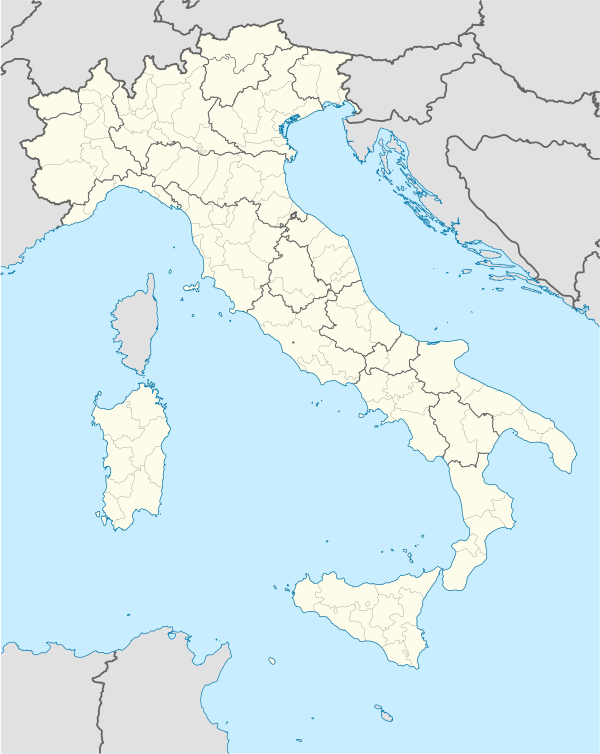

Luni Location of Luni in Italy | |

| Coordinates: 44°05′05.43″N 10°02′31.3″E / 44.0848417°N 10.042028°ECoordinates: 44°05′05.43″N 10°02′31.3″E / 44.0848417°N 10.042028°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Liguria |

| Province | La Spezia (SP) |

| Frazioni | Annunziata, Caffaggiola, Casano (communal seat), Dogana, Isola, Luni Scavi, Luni Mare, Luni Stazione, Nicola, Ortonovo, Serravalle |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Alessandro Silvestri |

| Area | |

| • Total | 13.86 km2 (5.35 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 76 m (249 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2015) | |

| • Total | 8,277 |

| • Density | 600/km2 (1,500/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Ortonovesi or Lunensi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 19034 |

| Dialing code | 0187 |

| Patron saint | Madonna del Mirteto |

| Saint day | 8 September |

| Website | Official website |

Luni is a comune (municipality) in the province of La Spezia, in the easternmost end of the Liguria region of northern Italy. It was founded by the Romans as Luna. It gives its name to Lunigiana, a region spanning eastern Liguria and northern Tuscany (province of Massa-Carrara).

The commune was known as Ortonovo (from the name of one of its current frazioni until April 2017. It is now named after the frazione of Luni.

Geography

Located in a plain near the Tyrrhenian Sea and close to the borders with Tuscany, Luni is crossed by the river Magra and lies between Sarzana (7 km in north) and Carrara (5 km in south). It is 4 km far from Ortonovo, 15 from Massa and 30 from La Spezia. The village is served by the National Highway 1 "Aurelia", crossed at Luni Mare by the A12 motorway and counts a railway station on the Pisa-Genoa line.

History

Luna was the frontier town of Etruria, on the left bank of the river Macra (now Magra), the boundary in imperial times between Etruria and Liguria. When the Romans first appeared in these parts, however, Etruscans and the Ligurians were already in possession of the territory.[1]

Early history

The city was established in 177 BC by Publius Aelius, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus and Gnaeus Sicinius[1][2] Located at the mouth of the Magra,[3] it was a military stronghold for the campaigns against the Ligures. An inscription of 155 BC, found in the forum of Luna in 1851, was dedicated to M. Claudius Marcellus in honor of his triumph over the Ligurians and Apuani. In 109 BC it was connected to Rome by the Via Aemilia Scauri, rebuilt in the 2nd century AD as the Via Aurelia. It flourished when exploitation of white marble quarries in the nearby Alpi Apuane and neighboring mountains of Carrara, which in ancient times bore the name of Luna marble.[4]. Pliny speaks of the quarries as only recently discovered in his day; they were soon owned by the imperial family. Pliny the Elder considered the big wheels of cheese from Luna the best in Etruria. Good wine was also produced.

Ancient harbour

It derived its importance mainly from its harbour,[5] which was on a gulf of the Tyrrhenian Sea now known as the Gulf of La Spezia, and not merely the estuary of the Macra as some authors supposed.[6][7] While the town was apparently not established until 177 BC,[8] when a colony of 2000 Roman citizens was founded there, the harbour is mentioned by Ennius, who sailed from there to Sardinia in 205 BC under Manlius Torquatus. It was also being contested by the Romans as early as 195 BC, who were fighting the Ligurians and Apuans in the area.[9] The site was used as a base for the quarrying of marble from the quarries of modern-day Carrara,[10] as the marble in that quarry is fine, and the harbour allowed the marble to be shipped to Rome easily.[6][11]

Late antiquity

In the 5th century, it was still notable, as it was chosen as the seat of a bishopric. Captured by the Goths in the following century, it was reconquered by the Byzantines in 552, who however lost it to the Lombards in 642. The latter damaged the city's economy, favouring the trades routes that passed through the nearby port of Lucca to the south. Luni had been reduced to a small village by the time of the Lombard king Liutprand. Later, it was a countship and see under Charlemagne, exactly on the border between the Kingdom of Italy and the Papal States.

Middle Ages

It was repeatedly sacked by sea pirates, Saracens in 849 and Vikings in 860. Luna is supposed to have been mistakenly sacked by the Viking leader Hastein, who thought it was Rome. He tricked his way in by pretending to be a dying Christian convert. 9th century Bishop Saint Ceccardo is celebrated on June 16.[12]

In the mid-10th century it experienced the last period of splendour under count Oberto I, who was lord of the whole Ligurian Mark, and momentarily repulsed the pirate threat. However, in the 990s the situation worsened again, and the episcopal see was moved, first to Carrara then, definitively, to Sarzana in 1207 (or 1204). In 1015 Luna was conquered by the Andalusian emir of Denia, Mujāhid with his Sardinian ships: when Pisa and Genoa beat back his forces, Luni was left destroyed. The spreading of malaria in the area and the silting up of the port contributed to the steep decline of Luni. In 1058 the whole population moved to Sarzana, while other refugees founded Ortonovo and Nicola. The title of bishop and count of Luni remained in use for various centuries, but Petrarch noted Luni as "once famous and powerful and now only a naked and useless name".

It was only in 1442 that the highly visible remains were identified with Luni and the Gulf of La Spezia recognized as its harbour.[13] The depredation of the Roman ruins of Luni aroused the concern of the local Cardinal Filippo Calandrini, who urged the Humanist pope Pius II to issue a brief (7 April 1461) forbidding any further dilapidations. It was of little practical use: when the Palazzo del Commune of Sarzana was constructed in 1471 dressed stone from Luni supplied a considerable part of the building material.[14] In 1510 the city council of Sarzana made a gift to the French governor at Genoa of a marble triton found at Luni.[15]

Archaeological excavations

Luni was excavated in the 1970s and many of the treasures brought to light are now housed in the adjacent museum (44°03′50″N 10°01′01″E / 44.064°N 10.017°E). Archeological evidence suggests that the Roman forum had been abandoned as a public space by the end of the sixth century, its buildings fell to ruin or were demolished and decorative marbles removed. Remains of small wooden houses were found in the space previously occupied by the forum.[16]

A theatre and an amphitheatre may still be distinguished on the site. No Etruscan remains have come to light. Cuntz's investigations (Jahreshefte des Osterr. Arch. Instituts, 1904, 46) seem to lead to the conclusion that an ancient road crossed the Apennines from it, following the line of the modern road (more or less that of the modern railway from Sarzana to Parma), and dividing near Pontremoli, one branch going to Borgotaro, Veleia and Placentia, and the other over the Cisa pass to Forum Novum (Fornovo) and Parma.

Main sights

Roman sights include remains of the elliptical Roman amphitheatre (1st century AD) and the Archaeological Museum.

Other sights include:

- Sanctuary of Nostra Signora del Mirteto, at Ortonovo, consecrated in 1566

- Torre di Guinigi, a medieval tower in Ortonovo

- Castle of Volpiglione, located between Castelpoggio and Ortonovo, dating from the 11th-12th centuries.

- Castle of Nicola (13th-15th century)

- 19th century municipal building, at Casano

References

- 1 2 Livy 41.13.4

- ↑ Inscriptions at Luna attest to the cult of the moon goddess Luna

- ↑ The modern coastline of the Portus Lunae noted by Strabo is now two km distant.

- ↑ Diana E. E. Kleiner. The Ascent of Augustus and Access to Italian Marble (Multimedia presentation). Yale University.

- ↑ Pliny NH 3.8; Strabo 5.2.5

- 1 2 Strabo 5.2.5

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Livy. AUC. 41.13.4.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Livy. AUC. 34.8.4-5,34.56.1-2, 39.21.1-539.32.1-3.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Strabo 5.2.5,

- ↑ Haegen, Anne Mueller von der; Strasser, Ruth F. (2013). "The White Gold of the Apuan Alps". Art & Architecture: Tuscany. Potsdam: H.F.Ullmann Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 978-3-8480-0321-1.

- ↑ http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/57500, http://catholicsaints.info/saint-ceccardus-of-luni/

- ↑ Giacomo Bracelli, Descriptio orae ligusticae, noted by Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity 1969:111.

- ↑ Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity (Oxford: Blackwell) 1969:112.

- ↑ Weiss 1969:114.

- ↑ Ward-Perkins, B. (1997) "Continuitists, catastrophists, and the towns of post-Roman Northern Italy", Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 65, pp. 157-176.

Sources

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Luni. |