Adenocarcinoma of the lung

| Adenocarcinoma of the lung | |

|---|---|

| |

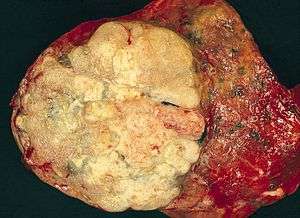

| A gross pathological specimen of a pulmonary adenocarcinoma, removed in a lobectomy. |

Adenocarcinoma of the lung (also known as pulmonary adenocarcinoma) is the most common type of lung cancer, and is characterized by distinct cellular and molecular features including gland and/or duct formation and/or production of significant amounts of mucus.[1] It is also classified as one of several non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), to distinguish it from small cell lung cancer which has a different behavior and prognosis.

Signs and symptoms

The most common signs of lung cancer include: [2]

- cough that does not go away or gets worse

- coughing up blood or rust-colored phlegm[3]

- chest pain, which may be aggravated by deep breathing, coughing, or laughing

- hoarseness

- weight loss and loss of appetite

- difficulty breathing

- generally feeling tired or weak

- recurring or unresolving lung infections (e.g. bronchitis and pneumonia)

- new onset of wheezing without history of asthma

Importantly, all of these signs are more commonly due to other causes which are not cancer. [2]

Causes

According to the Nurses' Health Study, the risk of pulmonary adenocarcinoma increases substantially after a long duration of tobacco smoking, with a previous smoking duration of 30-40 years giving a relative risk of approximately 2.4 compared to never-smokers, and a duration of more than 40 years giving a relative risk of approximately 5.[4]

This cancer usually is seen peripherally in the lungs, as opposed to small cell lung cancer and squamous cell lung cancer, which both tend to be more centrally located,[5][6] although it may also occur as central lesions.[6] For unknown reasons, it often arises in relation to peripheral lung scars. The current theory is that the scar probably occurred secondary to the tumor, rather than causing the tumor.[6] The adenocarcinoma has an increased incidence in smokers, and is the most common type of lung cancer seen in non-smokers and women.[6] The peripheral location of adenocarcinoma in the lungs may be due to the use of filters in cigarettes which prevent the larger particles from entering the lung.[7][8] Deeper inhalation of cigarette smoke results in peripheral lesions that are often the case in adenocarcinomas of the lung. Generally, adenocarcinoma grows more slowly and forms smaller masses than the other subtypes.[6] However, it tends to metastasize at an early stage.[6]

Molecular biology

Chromosomal rearrangements

Three membrane associated tyrosine kinase receptors are recurrently involved in rearrangements in adenocarcinomas: ALK, ROS1, and RET, and more than eighty other translocations have also been reported in adenocarcinomas of the lung.[9]

Targeted therapies: ALK and ROS1 fusions proteins are both sensitive to treatment with the new ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (see the Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology,[10]).

Gene mutations

Common gene mutations in pulmonary adenocarcinoma affect many genes, including EGFR (20%), HER2 (2%), KRAS, ALK, BRAF, PIK3CA, MET (1%, associated with resistant disease), and ROS1. Most of these genes are kinases, and can be mutated in different ways, including amplification.[11] The most commonly mutated gene across lung adenocarcinomas is TP53.[12]

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of lung cancer may be suspected on the basis of typical symptoms, particularly in a person with smoking history. Symptoms such as coughing up blood and unintentional weight loss may prompt further investigation, such as medical imaging.

Imaging

A chest x-ray (radiograph) is often the first imaging test performed when a person presents with cough or chest pain, particularly in the primary care setting. A chest radiograph may detect a lung nodule/mass that is suggestive of cancer, although sensitivity and specificity are limited.

CT imaging provides better evaluation of the lungs, with higher sensitivity and specificity for lung cancer compared to chest radiograph (although still significant false positive rate [13]). CT also allows for evaluation of other relevant anatomic structures such as nearby lymph nodes and bones, which may show evidence of metastatic spread of disease. Indeed, the US Preventative Services Task Force recommends annual screening with low-dose CT in adults aged 55 to 80 years who have a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years, with certain caveats (see Lung cancer screening).[14]

Nuclear medicine imaging, such as PET/CT and bone scan, may also be helpful to diagnose and detect metastatic disease elsewhere in the body. [3]

Histopathology

If possible, a biopsy of any suspected lung cancer is performed in order to perform a microscopic evaluation of the cells involved. [3]

Adenocarcinoma of the lung tends to stain mucin positive as it is derived from the mucus-producing glands of the lungs. Similar to other adenocarcinoma, if this tumor is well differentiated (low grade) it will resemble the normal glandular structure. Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma will not resemble the normal glands (high grade) and will be detected by seeing that they stain positive for mucin (which the glands produce). Adenocarcinoma can also be distinguished by staining for TTF-1, a cell marker for adenocarcinoma.[11]

To reveal the adenocarcinomatous lineage of the solid variant, demonstration of intracellular mucin production may be performed. Foci of squamous metaplasia and dysplasia may be present in the epithelium proximal to adenocarcinomas, but these are not the precursor lesions for this tumor. Rather, the precursor of peripheral adenocarcinomas has been termed atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH).[6] Microscopically, AAH is a well-demarcated focus of epithelial proliferation, containing cuboidal to low-columnar cells resembling club cells or type II pneumocytes.[6] These demonstrate various degrees of cytologic atypia, including hyperchromasia, pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli.[6] However, the atypia is not to the extent as seen in frank adenocarcinomas.[6] Lesions of AAH are monoclonal, and they share many of the molecular aberrations (like KRAS mutations) that are associated with adenocarcinomas.[6]

Classification

The category of adenocarcinoma includes are range of subtypes, and any one tumor tends to be heterogeneous in composition. Several major subtypes are currently recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1] and the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) / American Thoracic Society (ATS) / European Respiratory Society (ERS): [15][16][17]

- Non-invasive or minimally invasive adenocarcinoma

- Invasive adenocarcinoma

- Acinar predominant adenocarcinoma

- Papillary predominant adenocarcinoma

- Micropapillary predominant adenocarcinoma

- Solid predominant adenocarcinoma

- Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma

In as many as 80% of these tumors, components of more than one subtype will be recognized. Surgically resected tumors should be classified by comprehensive histological subtyping, describing patterns of involvement in increments of 5%. The predominant histologic subtype is then used to classify the tumor overall.[18] The predominant subtype is prognostic for survival after complete resection.[19]

Signet ring and clear cell adenocarcinoma are no longer histological subtypes, but rather cytological features that can occur in tumour cells of multiple histological subtypes, most often solid adenocarcinoma.[15]

Some variants are not clearly recognized by the WHO and IASLC/ATS/ERS classification:

Management

Adenocarcinoma is a non-small cell lung carcinoma, and as such, it is not as responsive to radiation therapy as is small cell lung carcinoma, but is rather treated surgically, for example by pneumonectomy or lobectomy.[6] Early stage disease is treated surgically. Targeted therapy is available for lung adenocarcinomas with certain mutations. Crizotinib is effective in tumors with fusions involving ALK or ROS1, whereas gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib are used in patients whose tumors have mutations in EGFR.[11]

Epidemiology

Incidence of pulmonary adenocarcinoma has been increasing in many developed Western nations in the past few decades, where it has become the most common type of lung cancer in both smokers (replacing squamous cell lung carcinoma) and lifelong non-smokers (<100 cigarettes in a lifetime).[1][23][24]

Nearly 40% of lung cancers in the US are adenocarcinoma.[11] Most cases are associated with smoking.[25]

References

- 1 2 3 Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, eds. (2004). Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart (PDF). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press. ISBN 92-832-2418-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-23. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- 1 2 "Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Signs and Symptoms". Cancer.org. American Cancer Society. May 16, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Tests for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer". American Cancer Society. June 23, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ↑ Kenfield SA, Wei EK, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA (June 2008). "Comparison of aspects of smoking among the four histological types of lung cancer". Tobacco Control. 17 (3): 198–204. doi:10.1136/tc.2007.022582. PMC 3044470. PMID 18390646.

- ↑ Travis WD, Travis LB, Devesa SS (January 1995). "Lung cancer". Cancer. 75 (1 Suppl): 191–202. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1+<191::AID-CNCR2820751307>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 8000996.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Mitchell RS, Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. "Chapter 13, box on morphology of adenocarcinoma". Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7.

- ↑ Goljan USMLE Audio Tapes, 2001

- ↑ Marugame T, Sobue T, Nakayama T, Suzuki T, Kuniyoshi H, Sunagawa K, Genka K, Nishizawa N, Natsukawa S, Kuwahara O, Tsubura E (February 2004). "Filter cigarette smoking and lung cancer risk; a hospital-based case--control study in Japan". British Journal of Cancer. 90 (3): 646–51. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601565. PMC 2409609. PMID 14760379.

- ↑ http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/Tumors/TranslocLungAdenocarcID6751.html

- ↑ "Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology". atlasgeneticsoncology.org.

- 1 2 3 4 World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.1. ISBN 9283204298.

- ↑ Greulich H (December 2010). "The genomics of lung adenocarcinoma: opportunities for targeted therapies". Genes & Cancer. 1 (12): 1200–10. doi:10.1177/1947601911407324. PMC 3092285. PMID 21779443.

- ↑ Gossner J (April 2014). "Lung cancer screening-don't forget the chest radiograph". World Journal of Radiology. 6 (4): 116–8. doi:10.4329/wjr.v6.i4.116. PMC 4000607. PMID 24778773.

- ↑ U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (December 2016). "Final Recommendation Statement: Lung Cancer: Screening". Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- 1 2 Van Schil PE, Asamura H, Rusch VW, Mitsudomi T, Tsuboi M, Brambilla E, Travis WD (February 2012). "Surgical implications of the new IASLC/ATS/ERS adenocarcinoma classification". The European Respiratory Journal. 39 (2): 478–86. doi:10.1183/09031936.00027511. PMID 21828029.

- ↑ Travis WD, Brambilla E, Van Schil P, Scagliotti GV, Huber RM, Sculier JP, Vansteenkiste J, Nicholson AG (August 2011). "Paradigm shifts in lung cancer as defined in the new IASLC/ATS/ERS lung adenocarcinoma classification". The European Respiratory Journal. 38 (2): 239–43. doi:10.1183/09031936.00026711. PMID 21804158.

- ↑ Vazquez M, Carter D, Brambilla E, Gazdar A, Noguchi M, Travis WD, Huang Y, Zhang L, Yip R, Yankelevitz DF, Henschke CI (May 2009). "Solitary and multiple resected adenocarcinomas after CT screening for lung cancer: histopathologic features and their prognostic implications". Lung Cancer. 64 (2): 148–54. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.08.009. PMC 2849638. PMID 18951650.

- ↑ Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, et al. (February 2011). "International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma". Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 6 (2): 244–85. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. PMC 4513953. PMID 21252716.

- ↑ Russell PA, Wainer Z, Wright GM, Daniels M, Conron M, Williams RA (September 2011). "Does lung adenocarcinoma subtype predict patient survival?: A clinicopathologic study based on the new International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary lung adenocarcinoma classification". Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 6 (9): 1496–504. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e318221f701. PMID 21642859.

- ↑ Yousem SA (June 2005). "Pulmonary intestinal-type adenocarcinoma does not show enteric differentiation by immunohistochemical study". Modern Pathology. 18 (6): 816–21. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800358. PMID 15605076.

- ↑ Lin D, Zhao Y, Li H, Xing X (February 2013). "Pulmonary enteric adenocarcinoma with villin brush border immunoreactivity: a case report and literature review". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 5 (1): E17–20. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.06.06. PMC 3547996. PMID 23372961.

- ↑ Smokers defined as current or former smoker of more than 1 year of duration. See image page in Commons for percentages in numbers. Reference:

- Table 2 in: Kenfield SA, Wei EK, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA (June 2008). "Comparison of aspects of smoking among the four histological types of lung cancer". Tobacco Control. 17 (3): 198–204. doi:10.1136/tc.2007.022582. PMC 3044470. PMID 18390646.

- ↑ Subramanian J, Govindan R (February 2007). "Lung cancer in never smokers: a review". Journal of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology. 25 (5): 561–70. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8015. PMID 17290066.

- ↑ Couraud S, Zalcman G, Milleron B, Morin F, Souquet PJ (June 2012). "Lung cancer in never smokers--a review". European Journal of Cancer. 48 (9): 1299–311. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2012.03.007. PMID 22464348.

- ↑ Horn L, Pao W, Johnson DH (2012). "Chapter 89". In Longo DL, Kasper DL, Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Loscalzo J. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-174889-X.