Mark 16

| Mark 16 | |

|---|---|

|

Luke 1 → | |

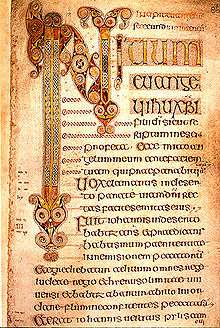

Image of page from the 7th-century Book of Durrow, from The Gospel of Mark, Trinity College Dublin | |

| Book | Gospel of Mark |

| Bible part | New Testament |

| Order in the Bible part | 2 |

| Category | Gospel |

| Gospel of Mark |

|---|

Mark 16 is the final chapter of the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It begins with the discovery of the empty tomb by Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome. There they encounter a young man dressed in white who announces the Resurrection of Jesus (16:1-6). The two oldest manuscripts of Mark 16 (from the 300s) then conclude with verse 8, which ends with the women fleeing from the empty tomb, and saying "nothing to anyone, because they were too frightened."[1]

Textual critics have identified two distinct alternative endings: the "Longer Ending" (vv. 9-20) and the "Shorter Ending" or "lost ending",[2] which appear together in six Greek manuscripts, and in dozens of Ethiopic copies. Modern versions of the New Testament generally include the Longer Ending.

Structure

The New King James Version organises this chapter as follows:

- Mark 16:1-8 = He is Risen

- Mark 16:9-11 = Mary Magdalene Sees the Risen Lord

- Mark 16:12-13 = Jesus Appears to Two Disciples

- Mark 16:14-18 = The Great Commission

- Mark 16:19-20 = Christ Ascends to God’s Right Hand

Alternative endings

Many scholars take Mark 16:8 as the original ending and believe that the longer ending (16:9-20) was a later addition. In this 12-verse passage, the author refers to Jesus' appearances to Mary Magdalene, two disciples, and then the Eleven (the Twelve Apostles excluding Judas). The text concludes with the Great Commission, declaring that believers that have been baptized will be saved while nonbelievers will be condemned, and pictures Jesus taken to Heaven and sitting at the Right Hand of God.[3]

The majority of scholars believe that verses 9-20 were not part of the original text, and were an addition by later Christians.[3] Because of patristic evidence from the late 100s for the existence of copies of Mark with 16:9-20, it is contended by some scholars that this passage must have been written and attached no later than the early 2nd century.[4] However, as the oldest copies of Mark, dating from the 4th century, do not include verses 9-20, textual evidence tends to support a relatively late insertion of the Great Commission - from the 4th century or later.[3]

Scholars are divided on the question of whether the "Longer Ending" was created deliberately to finish the Gospel of Mark (as contended by James Kelhoffer) or if it began its existence as a freestanding text which was used to "patch" the otherwise abruptly ending text of Mark.

A second issue is whether Mark intended the end of 16:8 or not; the references to a future meeting in Galilee between Jesus and the disciples (in Mark 14:28 and 16:7) could suggest that Mark intended to write beyond 16:8.[4] But there is scholarly work that suggests the "short ending" is more appropriate as it fits with the 'reversal of expectation' theme in the Gospel of Mark. [5]

The Council of Trent, reacting to Protestant criticism, defined the Canon of Trent which is the Roman Catholic biblical canon. The Decretum de Canonicis Scripturis, issued in 1546 at the fourth session of the Council, affirms that Jesus commanded that the gospel was "to be preached by His Apostles to every creature" — a statement clearly based on Mark 16:15. The decree proceeded to affirm, after listing the books of the Bible according to the Roman Catholic canon, that "If anyone receive not, as sacred and canonical, the said books entire with all their parts, as they have been used to be read in the Catholic Church, and as they are contained in the old Latin Vulgate edition, and knowingly and deliberately condemn the traditions aforesaid; let him be anathema."[6] Since Mark 16:9-20 is part of the Gospel of Mark in the Vulgate, and the passage has been routinely read in the churches since ancient times (as demonstrated by its use by Ambrose, Augustine, Peter Chrysologus, Severus of Antioch, Leo, etc.), the Council's decree affirms the canonical status of the passage. This passage was also used by Protestants during the Protestant Reformation; Martin Luther used Mark 16:16 as the basis for a doctrine in his Shorter Catechism. Mark 16:9-20 was included in the Rheims New Testament, the 1599 Geneva Bible, the King James Bible and other influential translations.

In most modern-day translations based primarily on the Alexandrian Text, it is included but is accompanied by brackets or by special notes, or both.

The empty tomb

Mark states that the Sabbath is now over and, just after sunrise, Mary Magdalene, another Mary, the mother of James,[7] and Salome (all also mentioned in Mark 15:40), come with spices to anoint Jesus' body. Luke 24:1 states that the women had "prepared" the spices. John 19:40 seems to say that Nicodemus had already anointed his body. John 20:1 and Matthew 28:1 simply say Mary went to the tomb, but not why.

The women wonder how they will remove the stone over the tomb. Upon their arrival, they find the stone already gone and go into the tomb. According to Kilgallen, this shows that in Mark's account they expected to find the body of Jesus.[8] Instead, they find a young man dressed in a white robe who is sitting on the right and who tells them:

"Don't be alarmed," he said. "You are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who was crucified. He has risen! He is not here. See the place where they laid him. But go, tell his disciples and Peter, 'He is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him, just as he told you.'"[9]

The white robe may be a sign that the young man is a messenger from God.[10] Matthew 28:5 describes him as an angel. In the account in Luke's gospel there were two men.[11] John says there were two angels, but that Mary saw them after finding the empty tomb and showing it to the other disciples. She comes back to the tomb, talks to the angels, and then Jesus appears to her.

Mark uses the word neaniskos for young, a word he also used to describe the man who fled at Jesus' arrest in Mark 14:51–52.[12] He is often thought of as an angel. Jesus had predicted his resurrection and returning to Galilee during the Last Supper in Mark.[13] Mark uses the passive verb form ēgerthē, translated "he was raised", indicating God raised him from the dead,[14] rather than "he is risen", as translated in the NIV.[15]

Peter, last seen in tears two mornings previously having denied any knowledge of Jesus [16] is mentioned in particular. Gregory the Great notes that "had the Angel not referred to him in this way, Peter would never have dared to appear again among the Apostles. He is bidden then by name to come, so that he will not despair because of his denial of Christ".[17]

The women, who are afraid (compare Mark 10:32), then flee and keep quiet about what they saw. Fear is the most common human reaction to the divine presence in the Bible.[10]

This is where the undisputed part of Mark's Gospel ends. Jesus is thus announced to have been raised from the dead and to have gone into Galilee.

Significance of ending at verse 8

Some interpreters have concluded that Mark's intended readers already knew the traditions of Jesus' appearances, and that Mark brings the story to a close here to highlight the resurrection and leave anticipation of the parousia (Second Coming).[18] Some have argued that this announcement of the resurrection and Jesus going to Galilee is the parousia (see also Preterism), but Raymond E. Brown argues that a parousia confined only to Galilee is improbable.[19] Gospel writer Mark gives no description of the resurrected Jesus, perhaps because Mark did not want to try to describe the nature of the divine resurrected Jesus.[20] Brown argues this ending is consistent with Mark's theology, where even miracles, such as the resurrection, do not produce the proper understanding or faith among Jesus' followers.[21] Having the women run away afraid is contrasted in the reader's mind with Jesus' appearances and statements which help confirm the expectation, built up in 8:31, 9:31, 10:34, and Jesus' prediction during the Last Supper of his rising after his death.[22] Richard A. Burridge argues that, in keeping with Mark's picture of discipleship, the question of whether it all comes right in the end is left open:

Mark's story of Jesus becomes the story of his followers, and their story becomes the story of the readers. Whether they will follow or desert, believe or misunderstand, see him in Galilee or remain staring blindly into an empty tomb, depends on us.[23]

Burridge goes on to compare the ending of Mark to its beginning:

Mark's narrative as we have it now ends as abruptly as it began. There was no introduction or background to Jesus' arrival, and none for his departure. No one knew where he came from; no one knows where he has gone; and not many understood him when he was here.[24]

Shorter Ending of Mark

The "Shorter Ending", with slight variations, runs as follows:

But they reported briefly to Peter and those with him all that they had been told. And after this, Jesus himself (appeared to them and) sent out by means of them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation.

In one Latin manuscript from c. 430, the "Shorter Ending" appears without the "Longer Ending". In this Latin copy (Codex Bobbiensis, "k"), the text of Mark 16 is anomalous:

- It contains an interpolation between 16:3 and 16:4 which appears to present Christ's ascension occurring at that point:

But suddenly at the third hour of the day there was darkness over the whole circle of the earth, and angels descended from the heavens, and as he [the Lord] was rising in the glory of the living God, at the same time they ascended with him; and immediately it was light.

- It omits the last part of 16:8

- It contains some variations in its presentation of the "Shorter Ending".

Other irregularities in Codex Bobbiensis lead to the conclusion that it was produced by a copyist (probably in Egypt) who was unfamiliar with the material he was copying.

Longer ending of Mark

In verses 9-16 the book describes Jesus appearing to Mary Magdalene, who is now described as someone whom Jesus healed from possession by seven demons. She then "tells the other disciples" what she saw, but no one believes her. Then Jesus appears "in a different form" to two unnamed disciples. They, too, are disbelieved when they tell what they saw. Jesus then appears at dinner to all the remaining eleven Apostles. He rebukes them for not believing the earlier reports of his resurrection and gives them instructions to go and preach his message to all creation (see also the Great Commission). Those who believe and are baptised will be saved, but unbelievers will be condemned. Belief and non-belief are a dominant theme in the Longer Ending: there are two references to believing (verses 16 and 17) and four references to not believing (verses 11, 13, 14 and 16). Johann Albrecht Bengel, in his Gnomon of the New Testament, defends the disciples: "They did believe: but presently there recurred to them a suspicion as to the truth, and even positive unbelief".[25]

Then in verses 17-18, Jesus states that believers will "speak in new tongues". They will also be able to handle snakes, be immune from any poison they might happen to drink, and will be able to heal the sick. Some interpreters, picturing an author putting words in Jesus' mouth, have suggested that these verses were a means by which early Christians asserted that their new faith was accompanied by special powers.[26]

By showing examples of unjustified unbelief in verses 10-13, and stating that unbelievers will be condemned and that believers will be validated by signs, the author may have been attempting to convince the reader to rely on what the disciples preached about Jesus.[27]

According to verse 19, Jesus then is taken up into heaven where, Mark claims, he sits at the right hand of God. Jesus quoted Psalm 110:1 in Mark 11 about the Lord sitting at the right hand of God.

After the ascension, his Eleven then went out and preached "everywhere" which is known as the Dispersion of the Apostles. Several signs from God accompanied their preaching. Where these things happened is not stated, but one could presume, from Mark 16:7, that they took place in Galilee. Luke-Acts, however, has this happening in Jerusalem.

Early evidence of the longer ending

The earliest clear evidence for Mark 16:9-20 as part of the Gospel of Mark is in Chapter XLV First Apology of Justin Martyr (c. 160). In a passage in which Justin treats Psalm 110 as a Messianic prophecy, he states that Psalm 110:2 was fulfilled when Jesus' disciples, going forth from Jerusalem, preached everywhere. His wording is remarkably similar to the wording of Mk. 16:20 and is consistent with Justin's use of a Synoptics-Harmony in which Mark 16:20 was blended with Lk. 24:53.

Justin's student Tatian (c. 172), incorporated almost all of Mark 16:9-20 into his Diatessaron, a blended narrative consisting of material from all four canonical Gospels.

Irenaeus (c. 184), in Against Heresies 3:10.6, explicitly cited Mark 16:19, stating that he was quoting from near the end of Mark's account. This patristic evidence is over a century older than the earliest manuscript of Mark 16.

Writers in the 200s such as Hippolytus of Rome and the anonymous author of De Rebaptismate also used the "Longer Ending".

In 305, the pagan writer Hierocles used Mark 16:18 in a jibe against Christians, probably recycling material written by Porphyry in 270.

Eusebius of Caesarea, in his Gospel Problems and Solutions to Marinus No. 1, writes toward the beginning of the fourth century, "One who athetises that pericope would say that it [i.e., a verse from the ending of Mark] is not found in all copies of the gospel according to Mark: accurate copies end their text of the Marcan account with the words of the young man whom the women saw, and who said to them: 'Do not be afraid; it is Jesus the Nazarene that you are looking for, etc.', after which it adds: 'And when they heard this, they ran away, and said nothing to anyone, because they were frightened.' That is where the text does end, in almost all copies of the gospel according to Mark. What occasionally follows in some copies, not all, would be extraneous, most particularly if it contained something contradictory to the evidence of the other evangelists."

Evidence of verse 8 ending

Theodore of Mopsuestia seems to have no knowledge of the longer ending, and, as he died in the first half of the fifth century, his testimony is interesting.

In his "Commentary on Nicene Creed" he says:

All the evangelists narrated to us His resurrection from the dead ... The blessed Luke, however, who is also the writer of a Gospel, added that He ascended into heaven so that we should know where He is after His resurrection.

Versions

| Version | Text |

|---|---|

| Mark 16:8[28] (undisputed text) | And they went out quickly, and fled from the sepulchre; for they trembled and were amazed: neither said they any thing to any man; for they were afraid. |

| Longer ending 16:9–14[29] | Now when Jesus was risen early the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, out of whom he had cast seven devils.

And she went and told them that had been with him, as they mourned and wept. And they, when they had heard that he was alive, and had been seen of her, believed not. After that he appeared in another form unto two of them, as they walked, and went into the country. And they went and told it unto the residue: neither believed they them. Afterward he appeared unto the eleven as they sat at meat, and upbraided them with their unbelief and hardness of heart, because they believed not them which had seen him after he was risen. |

| Freer Logion (between 16:14 and 16:15)[30] | And they excused themselves, saying, This age of lawlessness and unbelief is under Satan, who does not allow the truth and power of God to prevail over the unclean things dominated by the spirits.[31] Therefore, reveal your righteousness now. — thus they spoke to Christ. And Christ responded to them, The limit of the years of Satan's power is completed, but other terrible things draw near. And for those who sinned I was handed over to death, that they might return to the truth and no longer sin, in order that they might inherit the spiritual and incorruptible heavenly glory of righteousness. |

| Longer ending 16:15–20[29] | And he said unto them, Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature.

He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved; but he that believeth not shall be damned. And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover. So then after the Lord had spoken unto them, he was received up into heaven, and sat on the right hand of God. And they went forth, and preached every where, the Lord working with them, and confirming the word with signs following. Amen. |

| Shorter ending[30] | And they reported all the instructions briefly to Peter's companions. Afterwards Jesus himself, through them, sent forth from east to west the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation. Amen. (Greek text[32]) |

Hypotheses about the ending

Hypotheses on how to explain the textual variations include:

- Mark intentionally ended his Gospel at 16:8, and someone else (later in the transmission-process) composed the "Longer Ending" as a conclusion to what was interpreted to be a too-abrupt account.

- Mark did not intend to end at 16:8, but was somehow prevented from finishing (perhaps by his own death or sudden departure from Rome), whereupon another person finished the work (still in the production-stage, before it was released for church-use) by attaching material from a short Marcan composition about Jesus' post-resurrection appearances.

- Mark wrote an ending which was accidentally lost (perhaps as the last part of a scroll which was not rewound, or as the outermost page of a codex which became detached from the other pages), and someone in the 100's composed the "Longer Ending" as a sort of patch, relying on parallel-passages from the other canonical Gospels.

- Verses 16:9–20 were written by Mark and were omitted or lost from Sinaiticus and Vaticanus for one reason or another, perhaps accidentally, perhaps intentionally. (Possibly a scribe regarded John 21 as a better sequel to Mark's account, and considered the "Longer Ending" superfluous.)

- Mark wrote an ending, but it was suppressed and replaced with 16:9–20, which are a pastiche of parallel passages from the other canonical Gospels.

External evidence

Manuscripts omitting Mark 16:9–20

The last twelve verses, 16:9–20, are not present in two 4th-century manuscripts: Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus, the earliest complete manuscripts of Mark.

(Papyrus 45 is the oldest extant manuscript that contains text from Mark, but it has no text from chapter 16 due to extensive damage).

Codex Vaticanus (4th century) has a blank column after ending at 16:8 and placing kata Markon, "according to Mark". There are three other blank columns in Vaticanus, in the Old Testament, but they are each due to incidental factors in the production of the codex: a change to the column-format, a change of scribes, and the conclusion of the Old Testament portion of the text. The blank column between Mark 16:8 and the beginning of Luke, however, is deliberately placed.

It has been suggested that Codex Vaticanus may be reflecting a Western order of the gospels with Mark as the last book (Matthew, John, Luke, and Mark).

Other manuscripts that omit the last twelve verses include: minuscule 304 (12th century), Syriac Sinaiticus (from the late 4th-century), and a Sahidic manuscript.

In addition to these, over 100 Armenian manuscripts, as well as the two oldest Georgian manuscripts, also omit the appendix.

The Armenian Version was made in 411-450, and the Old Georgian Version was based mainly on the Armenian Version.

Manuscripts adding a shorter ending after verse 8

Codex Bobiensis (4th or 5th century, Latin).

Also inserts a unique interpolation between 16:3 and 16:4 and with the last phrase of 16:8 omitted.

Manuscripts adding a shorter ending and verses 9–20

Six Greek manuscripts add the "shorter ending" after 16:8 and follow it with vv. 9–20. Includes: Codex L (019), Codex Ψ (044), Uncial 083, Uncial 099

minuscule 274 (margin), minuscule 579, lectionary 1602.

Syriac Harclean margin.

Ethiopic manuscripts.

Coptic texts: Sahidic manuscripts, Bohairic manuscripts (Huntington MS 17).

Manuscripts adding verses 9–20

A group of manuscripts known as "Family 13" adds Mark 16:9–20 in its traditional form.

Including about a dozen uncials (the earliest being Codex Alexandrinus) and in all undamaged minuscules.[33]

Uncials: A, C, D, W, Codex Koridethi, and minuscules: 33, 565, 700, 892, 2674.

The Majority/Byzantine Text (over 1,200 manuscripts of Mark); the Vulgate and part of the Old Latin, Syriac Curetonian, Peshitta, Bohairic, Gothic;[34]

Manuscripts adding verses 9–20 with a notation

A group of manuscripts known as "Family 1" add a note to Mark 16:9–20, stating that some copies do not contain the verses.

Including minuscules: 22, 138, 205, 1110, 1210, 1221, 1582.

One Armenian manuscript, Matenadaran 2374 (formerly known as Etchmiadsin 229), made in 989, features a note, written between 16:8 and 16:9, Ariston eritzou, that is, "By Ariston the Elder/Priest".

Ariston, or Aristion, is known from early traditions (preserved by Papias and others) as a colleague of Peter and as a bishop of Smyrna in the first century.

Manuscripts adding verses 9–20 without divisions

A group of manuscripts known as "Family K1" add Mark 16:9-10 without numbered κεφαλαια (chapters) at the margin and their τιτλοι (titles) at the top (or the foot).[35]

Including: Minuscule 461.

Manuscripts adding verses 9–20 with an extra passage

Noted in manuscripts according to Jerome.

Codex Washingtonianus (late 4th, early 5th century) includes verses 9–20 and features an addition between 16:14-15 known as the "Freer Logion":

And they excused themselves, saying, "This age of lawlessness and unbelief is under Satan, who does not allow the truth and power of God to prevail over the unclean things of the spirits [or, does not allow what lies under the unclean spirits to understand the truth and power of God]. Therefore reveal your righteousness now" – thus they spoke to Christ. And Christ replied to them, "The term of years of Satan's power has been fulfilled, but other terrible things draw near. And for those who have sinned I was handed over to death, that they may return to the truth and sin no more, in order that they may inherit the spiritual and incorruptible glory of righteousness that is in heaven."[36]

Writings of the Church Fathers

- Omits: Eusebius, manuscripts according to Eusebius, manuscripts according to Jerome (who was recycling part of Eusebius' statements, condensing them as he loosely rendered them into Latin).

- Adds: Irenaeus, manuscripts according to Eusebius, Marinus, Acts of Pilate, manuscripts according to Jerome (add with obeli f 1 al), Ambrose, Aphraates, Augustine, Augustine's Latin copies, Augustine's Greek manuscripts, Tatian's Diatessaron, Eznik of Golb, Pelagius, Nestorius, Patrick, Prosper of Aquitaine, Leo the Great, Philostorgius, Life of Samson of Dol, Old Latin breves, Marcus Eremita, Peter Chrysologus. Also, Fortunatianus (c. 350) states that Mark mentions Jesus' ascension.

Internal evidence

Critical questions concerning the authenticity of verses 9–20 (the "longer ending") often center on stylistic and linguistic issues. On linguistics, E. P. Gould identified 19 of the 163 words in the passage as distinctive and not occurring elsewhere in the Gospel.[37] Dr. Bruce Terry argues that a vocabulary-based case against Mark 16:9–20 is indecisive, inasmuch as other 12-verse sections of Mark contain comparable numbers of once-used words.[38]

The final sentence in verse 8 is regarded as strange by some scholars. In the Greek text, it finishes with the conjunction γαρ (gar, "for"). It is contended by some who see 16:9–20 as originally Markan that γαρ literally means because, and this ending to verse 8 is therefore not grammatically coherent (literally, it would read they were afraid because). However, γαρ may end a sentence and does so in various Greek compositions, including some sentences in the Septuagint, a popular Greek translation of the Old Testament used by early Christians. Protagoras, a contemporary of Socrates, even ended a speech with γαρ. Although γαρ is never the first word of a sentence, there is no rule against it being the last word, even though it is not a common construction. However, if the Gospel of Mark intentionally concluded with this word, it would be the only narrative in antiquity to do so.

Robert Gundry mentions that only about 10% of Mark's γαρ clauses (6 out of 66) conclude pericopes.[39] Thus he infers that, rather than concluding 16:1–8, verse 8 begins a new pericope, the rest of which is now lost to us. Gundry therefore does not see verse 8 as the intended ending; a resurrection narrative was either written, then lost, or planned but never actually written.

Concerning style, the degree to which verses 9–20 aptly fit as an ending for the Gospel remains in question. The turn from verse 8 to 9 has also been seen as abrupt and interrupted: the narrative flows from "they were afraid" to "now after he rose", and seems to reintroduce Mary Magdalene. Secondly, Mark regularly identifies instances where Jesus' prophecies are fulfilled, yet Mark does not explicitly state the twice predicted reconciliation of Jesus with his disciples in Galilee (Mark 14:28, 16:7). Lastly, the active tense "he rose" is different from the earlier passive construction "[he] has been risen" of verse 6, seen as significant by some.[40]

Sinaiticus and Vaticanus

According to T. C. Skeat, Sinaiticus and Vaticanus were both produced at the same scriptorium, which would mean that they represent only one textual tradition, rather than serving as two independent witnesses of an earlier text type that ends at 16:8.[41] Skeat argued that they were produced as part of Eusebius' response to the request of Constantine for copies of the scriptures for churches in Constantinople.[42]

However, that is unlikely, since there are about 3,036 differences between the Gospels of Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, and in particular the text of Sinaiticus is of the so-called Western text form in John 1:1 through 8:38 while Vaticanus is not. Also against the theory that Eusebius directed the copying of both manuscripts is the fact that neither Vaticanus nor Sinaiticus contains Mark 15:28, which Eusebius accepted and included in his Canon-tables,[43] and Vaticanus and Sinaiticus both include a reading at Matthew 27:49 about which Eusebius seems to have been completely unaware. Finally, there is a significant relationship between Codex Vaticanus and papyrus P75, indicating that the two bear a remarkable relationship to one another—one that is not shared by Codex Sinaiticus. P75 is much older than either, having been copied prior to the birth of Eusebius.[44] Therefore, both manuscripts were not transcribed from the same exemplar and were not associated with Eusebius. The evidence presented by Skeat sufficiently shows that the two codices were made at the same place, and that the place in question was Caesarea, and that they almost certainly shared a copyist, but the differences between the manuscripts can be better explained by other theories.

Scholarly opinions

Currently a majority of scholars agree that verses 9–20 were not part of the original text of Mark but represent a very early addition.[45]

Explaining his own belief as to why the verses were added, text critic and author Bart D. Ehrman says:

Jesus does rise from the dead in Mark's Gospel. The women go to the tomb, the tomb is empty and there is a man there who tells them that Jesus has been raised from the dead and that they are to go tell the disciples that this has happened. But then the Gospel ends in Codex Sinaiticus and other manuscripts by saying the women fled from the tomb and didn't say anything to anyone because they were afraid, period. That's where the Gospel ends. So nobody finds out about it, the disciples don't learn about it, the disciples never see Jesus after the resurrection, that's the end of the story. But later scribes couldn't handle this abrupt ending and they added the 12 verses people find in the King James Bible or other Bibles in which Jesus does appear to his disciples.[46]

Among the scholars who reject Mark 16:9–20, a debate continues about whether the ending at 16:8 is intentional or accidental. Some scholars consider the original ending to have been verse 8. Others argue that Mark never intended to end so abruptly: either he planned another ending that was never written, or the original ending has been lost. C. H. Turner argued that the original version of the Gospel could have been a codex, with the last page being especially vulnerable to damage. Whatever the case, many scholars, including Rudolf Bultmann, have concluded that the Gospel most likely ended with a Galilean resurrection appearance and the reconciliation of Jesus with the Eleven,[47] even if verses 9–20 were not written by the original author of the Gospel of Mark.

Verses 9–20 share the subject of Jesus' post-resurrection appearances, and other points, with other passages in the New Testament. This has led some scholars to believe that Mark 16:9–20 is based on the other books of the New Testament. Some of the elements that Mark 16:9–20 has in common with other passages of Scripture are listed here:

- v.9 seven demons were cast out of Mary Magdalene (Luke 8:2);

- v.11 they refused to believe it (Luke 24:10–11);

- v.12–13a two returned and told the others (Luke 24:13–35);

- v.14 appeared to the Eleven (Luke 24:36–43, John 20:19–29, 1 Cor 15:5);

- v.15 Great Commission (Matthew 28:19, Acts 1:8);

- v.16 salvation and judgment (Acts 2:38, 16:31–33);

- v.17a cast out demons (Luke 10:17, Acts 5:16, 8:7, 16:18, 19:12);

- v.17b speak with new tongues (Acts 2:4),

- v.18a pick up serpents (Luke 10:19, Acts 28:5);

- v.18c lay hands on the sick (Mark 5:23, Acts 6:6, 9:17, 28:8);

- v.19a ascension of the Lord Jesus (Luke 24:51, John 20:17, Acts 1:2, Acts 1:9–11);

- v.19b sat down at the right hand of God, (Acts 7:55, Rom 8:34, Eph 1:20, Col 3:1);

- v.20 confirmed the word by the signs that followed (Acts 14:3).

Jesus' reference to drinking poison (16:18) does not correspond to a New Testament source, but that miraculous power did appear in Christian literature from the 2nd century CE on.[4]

Scholarly conclusions

The vast majority of contemporary New Testament textual critics have concluded that neither the longer nor shorter endings were originally part of Mark's Gospel. This conclusion extends back as far as the middle of the nineteenth century. Harnack, for instance, was convinced that the original ending was lost.[48] Rendel Harris (1907) supplied the theory that Mark 16:8 had continued with the words "of the Jews."[49] By the middle of the 20th century, it had become the dominant belief that the Long Ending was not genuine. By this time, most translations were adding notes to indicate that neither the Long Ending nor the Short Ending were original. Examples include Mongomery's NT ("The closing verses of Mark's gospel are probably a later addition...," 1924); Goodspeed's (who includes both endings as "Ancient Appendices," 1935); Williams' NT ("Later mss add vv. 9-20," 1937); and the Revised Standard Version (1946), which placed the Long Ending in a footnote. Tradition intervened, and by the early 1970s the complaints in favor of the verses were strong enough to prompt a revision of the RSV (1971) which restored the verses to the text—albeit with a note about their dubiousness. The vast majority of modern scholars remain convinced that neither of the two endings is Marcan.

In Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament,[50] Metzger states: "Thus, on the basis of good external evidence and strong internal considerations it appears that the earliest ascertainable form of the Gospel of Mark ended with 16:8. Three possibilities are open: (a) the evangelist intended to close his Gospel at this place; or (b) the Gospel was never finished; or, as seems most probable, (c) the Gospel accidentally lost its last leaf before it was multiplied by transcription."

The 1984 printing of the NIV translation notes: "The most reliable early manuscripts and other ancient witnesses do not have Mark 16:9–20." However, the Committee on Bible Translation has since changed this to read "The earliest manuscripts and some other ancient witnesses do not have Mark 16:9–20."

In 2014, Nicholas P. Lunn published the book "The Original Ending of Mark: A New Case for the Authenticity of Mark 16: 9-20", in which he argued for the authenticity of the longer end of the Gospel of Mark. The work itself was very warmly welcomed by the scientific community, Pieter J. Lalleman said that this book should become a compulsory read for anyone who deals with the Gospel of Mark, and Maurice A. Robinson recognized that the book would encourage the scientific community to undertake further research on the ending of the Gospel. Craig Evans, who influenced the book, changed his view of the ending of the Gospel of Mark, saying that it would influence opinion about Mark's longer ending within the scientific community:

Nicholas Lunn has thoroughly shaken my views concerning the ending of the Gospel of Mark. As in the case of most gospel scholars, I have for my whole career held that Mark 16:9-20, the so-called 'Long Ending,' was not original. But in his well-researched and carefully argued book, Lunn succeeds in showing just how flimsy that position really is. The evidence for the early existence of this ending, if not for its originality, is extensive and quite credible. I will not be surprised if Lunn reverses scholarly opinion on this important question. I urge scholars not to dismiss his arguments without carefully considering this excellent book. The Original Ending of Mark is must reading for all concerned with the gospels and early tradition concerned with the resurrection story.[51]

— Craig A. Evans, Payzant Distinguished Professor of New Testament, Acadia Divinity College, Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada

Theological implications

Few doctrines of the mainline Christian denominations stand or fall on the support of the longer ending of Mark. The longer ending does identify Mary Magdalene as the woman out of whom Jesus had exorcised seven demons (but so does Luke 8:2), but Mary Magdalene's significance, and the practice of exorcism, are both supported by New Testament texts outside the debated passage.

The longer ending of Mark 16 is of considerable significance in Pentecostalism and other denominations:

- Mark 16:16 is cited as evidence for the requirement of believer's baptism among churches of the Restoration Movement, but Acts 2:38 and other texts also are used to support this position.

- Mark 16:17 is specifically cited as Biblical support for some of these denominations' teachings concerning exorcism and spiritual warfare, and also in support of speaking in tongues.

- The practice of snake handling and of drinking strychnine and other poisons, found in a few offshoots of Pentecostalism, find their Biblical support in Mark 16:18. These churches typically justify these practices as "confirming the word with signs following" (KJV), which references Mark 16:20. Other denominations believe that these texts indicate the power of the Holy Spirit given to the apostles, but do not believe that they are recommendations for worship.

The longer ending was declared canonical scripture by the Council of Trent. Today, however, Roman Catholics are not required to believe that Mark wrote this ending.[19] The Catholic NAB translation includes the footnote: "[9–20] This passage has traditionally been accepted as a canonical part of the gospel and was defined as such by the Council of Trent. Early citations of it by the Fathers indicate that it was composed by the second century, although vocabulary and style indicate that it was written by someone other than Mark. It is a general resume of the material concerning the appearances of the risen Jesus, reflecting, in particular, traditions found in Luke 24 and John 20."

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mark 16:1-8: New Living Translation: "The most ancient manuscripts of Mark conclude with verse 16:8. Later manuscripts add one or both of the following endings ..."

- ↑ Jerusalem Bible, footnote at Mark 16:8

- 1 2 3 Funk, Robert W. and the 1985 Jesus Seminar. The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. "Empty Tomb, Appearances & Ascension" p. 449-495.

- 1 2 3 May, Herbert G. and Bruce M. Metzger. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. 1977.

- ↑ MacDonald, Dennis R. Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark, by Dennis R. MacDonald, Pages 42, 70, 175, 213

- ↑ Hanover Historical Texts Project, The Council of Trent: The Fourth Session, accessed 29 June 2017

- ↑ Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses (Cambridge: Eerdmans, 2006), p. 50 n. 43.

- ↑ Kilgallen, p. 297

- ↑ Mark 16:6–7

- 1 2 Kilgallen, p. 300

- ↑ Luke 24:4-5

- ↑ Brown et al., p. 629

- ↑ Mark 14:28

- ↑ "God raised him [Jesus] from the dead" Acts 2:24, Romans 10:9, 1 Cor 15:15; also Acts 2:31–32, 3:15, 3:26, 4:10, 5:30, 10:40–41, 13:30, 13:34, 13:37, 17:30–31, 1 Cor 6:14, 2 Cor 4:14, Gal 1:1, Eph 1:20, Col 2:12, 1 Thess 1:10, Heb 13:20, 1 Pet 1:3, 1:21

- ↑ See for example Mark 16:6 in the NRSV) and in the creeds. Brown et al., p. 629 (Greek distinguished passive from middle voice in the aorist tense used here.)

- ↑ Mark 14:66-72

- ↑ Saint Gregory the Great's Sermon on the Mystery of the Resurrection, accessed 13 December 2017

- ↑ Brown et al., p. 628

- 1 2 Brown, p. 148

- ↑ Kilgallen, p. 303

- ↑ Kilgallen, p. 148

- ↑ Miller, p. 52

- ↑ Richard A. Burridge, Four Gospels, One Jesus? A Symbolic Reading (2nd ed., Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 64.

- ↑ Richard A. Burridge, Four Gospels, One Jesus? A Symbolic Reading (2nd ed., Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 64-65.

- ↑ Bengel's Gnomon of the New Testament on Mark 16, accessed 14 December 2017

- ↑ Kilgallen, p. 309

- ↑ Brown, p. 149

- ↑ Mark 16:8

- 1 2 Mark 16:9-20

- 1 2 United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, New American Bible

- ↑ or, "does not allow the unclean things dominated by the spirits to grasp the truth and power of God"

- ↑ UBS Greek New Testament p147 Παντα δε τα παρηγγελμενα τοις περι τον Πετρον συντομως εξηγγειλαν. μετα δε ταυτα και αυτος ο Ι{ησου}ς εφανη αυτοις, και απο ανατολης και αχρι δυσεως εξαπεστειλεν δι αυτων το ιερον και αφθαρτον κηρυγμα της αιωνιου σωτηριας. αμην.

- ↑ Most textual critics are skeptical of the weight of the bulk of minuscules, since most were produced in the Middle Ages, and possess a high degree of similarity.

- ↑ via the Speyer fragment. Carla Falluomini, The Gothic Version of the Gospels and Pauline Epistles,

- ↑ Hermann von Soden, Die Schriften des Neuen Testaments, I/2, p. 720.

- ↑ Bruce M. Metzger, Textual Commentary, p. 104

- ↑ E. P. Gould, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to St. Mark (New York: Charles Scribner's Press, 1896), p. 303.

- ↑ "The Style of the Long Ending of Mark" by Dr. Bruce Terry at http://bterry.com/articles/mkendsty.htm

- ↑ Grundy, Robert. Mark: A Commentary on His Apology for the Cross, Chapters 9–16

- ↑ Kilgallen, p. 306.

- ↑ T. C. Skeat, "The Codex Sinaiticus, the Codex Vaticanus, and Constantine", in Journal of Theological Studies 50 (1999), 583-625.

- ↑ T. C. Skeat, "The Codex Sinaiticus, the Codex Vaticanus, and Constantine", in Journal of Theological Studies 50 (1999), 604-609.

- ↑ Section 217, Column 6

- ↑ Epp 1993, p. 289

- ↑ Iverson, Kelly (April 2001). Irony in the End: A Textual and Literary Analysis of Mark 16:8. Evangelical Theological Society Southwestern Regional Conference. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ↑ BBC Radio 4 programme on 05/Oct/2008 "The Oldest Bible"

- ↑ R. Bultmann, History of the Synoptic Tradition pp. 284-286.

- ↑ Bruchstücke des Evangeliums und der Apokalypse des Petrus, 1893, p. 33

- ↑ Side-Lights on New Testament Research, p. 88

- ↑ page 126

- ↑ P. Lunn, Nicholas. "The Original Ending of Mark: A New Case for the Authenticity of Mark 16:9-20".

References

- Beavis, M. A., Mark's Audience, Sheffield, Sheffield Academic Press, 1989. ISBN 1-85075-215-X.

- Brown, Raymond E. An Introduction to the New Testament. Doubleday, 1997. ISBN 0-385-24767-2

- Brown, Raymond E. et al. The New Jerome Biblical Commentary. Prentice Hall, 1990 ISBN 0-13-614934-0

- Elliott, J. K., The Language and Style of the Gospel of Mark. An Edition of C. H. Turner's "Notes on Markan Usage" together with Other Comparable Studies, Leiden, Brill, 1993. ISBN 90-04-09767-8.

- Epp, Eldon Jay. "The Significance of the Papyri for Determining the Nature of the New Testament Text in the Second Century: A Dynamic View of Textual Transmission". In Epp, Eldon Jay; Fee, Gordon D. Studies in the Theory and Method of New Testament Textual Criticism. Eerdmans, 1993. ISBN 0-8028-2773-X.

- Gundry, R. H., Mark: A Commentary on His Apology for the Cross, Chapters 9–16, Grand Rapids, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1992. ISBN 0-8028-2911-2.

- Kilgallen, John J. A Brief Commentary on the Gospel of Mark. Paulist Press, 1989. ISBN 0-8091-3059-9

- MacDonald, Dennis R. "The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark" Yale University Press, 2000 ISBN 0-300-08012-3

- Mark 16 NIV

- Miller, Robert J. (ed.), The Complete Gospels. Polebridge Press, 1994. ISBN 0-06-065587-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gospel of Mark - Chapter 16. |

- WELS Topical Q&A: Mark 16:9-20 - Inspiration, Signs, Miracles - believing that Mark 16:9-20 clearly belong in the sacred text without reservation

- Mark 16 in Manuscript Comparator — allows two or more New Testament manuscript editions' readings of the passage to be compared in side-by-side and unified views (similar to diff output)

- The various endings of Mark Detailed text-critical description of the evidence, the manuscripts, and the variants of the Greek text (PDF, 17 pages)

- Extracts from authors arguing for the authenticity of Mark 16:9–20

- Aichele, G., "Fantasy and Myth in the Death of Jesus" A literary-critical affirmation of Mark's Gospel ending at 16:8.

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Gospel of Saint Mark: Section IV. STATE OF TEXT AND INTEGRITY

- Last Twelve Verses of the Gospel According to S. Mark Vindicated Against Recent Critical Objectors and Established A Book written by Burgon, John William

- The Authenticity of Mark 16:9–20 A detailed defense of Mark 16:9–20, featuring replicas of portions of Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus and a list of early patristic evidence. See also http://www.curtisvillechristianchurch.org/AuthSuppl.htm for manuscript-images and other materials.

- Mark 16:9-20 as Forgery or Fabrication A detailed case against Mark 16:9–20, including all relevant stylistic, textual, manuscript, and patristic evidence, and an extensive bibliography.

| Preceded by Mark 15 |

Chapters of the Bible Gospel of Mark |

Succeeded by Luke 1 |