The Story of Little Black Sambo

1st edition | |

| Author | Helen Bannerman |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Helen Bannerman |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Publisher | Grant Richards, London |

Publication date | 1899 |

| Media type | |

The Story of Little Black Sambo is a children's book written and illustrated by Scottish author Helen Bannerman, and published by Grant Richards in October 1899 as one in a series of small-format books called The Dumpy Books for Children. The story was a children's favourite for more than half a century.

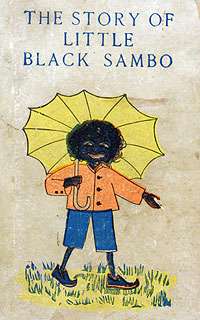

Critics of the time observed that Bannerman presents one of the first black heroes in children's literature and regarded the book as positively portraying black characters in both the text and pictures, especially in comparison to the more negative books of that era that depicted blacks as simple and uncivilised.[1] However, it would become an object of allegations of racism in the mid-20th century, due to the names of the characters being racial slurs for dark-skinned people, and the fact the illustrations were in the, as Langston Hughes put it, pickaninny style.[2] Both text and illustrations have undergone considerable revisions since.

Plot

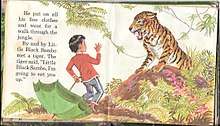

Sambo is a South Indian boy who lives with his father and mother, named Black Jumbo and Black Mumbo, respectively. While out walking, Sambo encounters four hungry tigers, and surrenders his colourful new clothes, shoes, and umbrella so they will not eat him. The tigers are vain and each thinks Sambo's clothes are the best. They chase each other around a tree until they are reduced to a pool of ghee (clarified butter). Sambo then recovers his clothes and collects the ghee, which his mother uses to make pancakes.[3]

Controversy

The book's original illustrations were done by the author and simple in style, typical of most children's books, and depicted Sambo as a Southern Indian or Tamil child. The book has thematic similarities to Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book, published in 1894, which had far more sophisticated illustrations. However, Little Black Sambo's success led to many counterfeit, inexpensive, widely available versions that incorporated popular stereotypes of "black" peoples. For example, in 1908 John R. Neill, best known for his illustration of the Oz books by L. Frank Baum, illustrated an edition of Bannerman's story.[4] In 1932 Langston Hughes criticised Little Black Sambo, despite its being set in India, as a typical "pickaninny" storybook which was hurtful to black children, and gradually the book disappeared from lists of recommended stories for children.[5]

In 1942, Saalfield Publishing Company released a version of Little Black Sambo illustrated by Ethel Hays.[6] In 1943, Julian Wehr created an animated version.[7] During the mid-20th century, however, some American editions of the story, including a 1950 audio version on Peter Pan Records, changed the title to the racially neutral Little Brave Sambo.

The book is beloved in Japan and is not considered controversial there, but it was subject to copyright infringement. Little Black Sambo (ちびくろサンボ Chibikuro Sanbo) was first published in Japan by Iwanami Shoten Publishing in 1953. The book was an unlicensed version of the original, and it contained drawings by Frank Dobias that had appeared in a US edition published by Macmillan Publishers in 1927. Sambo was illustrated as an African boy rather than as an Indian boy. Although it did not contain Bannerman's original illustrations, this book was long mistaken for the original version in Japan. It sold over 1,000,000 copies before it was pulled off the shelves in 1988 after copyright issues were raised.[8] When the copyright expired, Kodansha and Shogakukan, the two largest publishers in Japan, published official editions. These are still in print. And as of August 2011, an equally uncontroversial "side story" for Little Black Sambo, called Ufu and Mufu, is being sold and merchandised in Japan.

The above description does not match with a Japanese account of why the books were terminated from publication. According to this account, The Association to Stop Racism Against Blacks launched a complaint against all major publishers in Japan that published variations of the story, and this triggered self-censorship among those publishers.[9][10] In 2005, after copyright of the 1953 Iwanami Shoten Publishing edition of the book expired, Zuiunsya reprinted the original version and sold more than 150,000 copies within five months' time. The reprinting caused criticism from media outside Japan, such as The Los Angeles Times.[10]

Modern versions

In 1961, Whitman Publishing Company released an edition illustrated by Violet LaMont. Her colorful pictures show an Indian family wearing bright Indian clothes. The story of the boy and tigers is as described in the plot section above.

In 1996, noted illustrator Fred Marcellino observed that the story itself contained no racist overtones and produced a re-illustrated version, The Story of Little Babaji, which changes the characters' names but otherwise leaves the text unmodified.[11]

Julius Lester, in his Sam and the Tigers, also published in 1996, recast "Sam" as a hero of the mythical Sam-sam-sa-mara, where all the characters were named "Sam".[12]

A modern printing with the original title, in 2003, substituted more racially sensitive illustrations by Christopher Bing, in which, for example, Sambo is no longer so inky black. It was chosen for the Kirkus 2003 Editor's Choice list. Some critics were still unsatisfied. Dr Alvin F. Poussaint said of the 2003 publication: "I don't see how I can get past the title and what it means. It would be like ... trying to do 'Little Black Darky' and saying, 'As long as I fix up the character so he doesn't look like a darky on the plantation, it's OK.'"[13]

In 1997, Kitaooji Shobo Publishing in Kyoto obtained formal license from the UK publisher, and republished the work under the title of Chibikuro Sambo ("Chibi" means "little" and "kuro" means black). The protagonist is depicted as a black Labrador puppy that goes for a stroll in the jungle; no humans appear in the edition. The Association To Stop Racism Against Blacks still refers to the book in this edition as discriminatory.

Bannerman's original was first published with a translation of Masahisa Nadamoto by Komichi Shobo Publishing, Tokyo, in 1999.

In 2004, a Little Golden Book version was published, The Boy and the Tigers, with new names and illustrations by Valeria Petrone. The boy is called Little Rajani.[14]

The Iwanami version, with its controversial Dobias illustrations and without the proper copyright, was re-released in April 2005 in Japan by a Tokyo-based publisher Zuiunsya, because Iwanami's copyright expired fifty years after its first appearance.

It was retold as "Little Kim" in a storybook and cassette as part of the Once Upon a Time Fairy Tale Series where Sambo is called "Kim", his father Jumbo is "Tim" and his mother Mumbo is "Sim".

Adaptations

A board game was produced in 1924 and re-issued in 1945, with different artwork. Essentially the game followed the storyline, starting and ending at home.

In the 1930s, Wyandotte Toys used a pickaninny caricature "Sambo" image for a dart-gun target.[15]

An animated version of the story was produced in 1935 as part of Ub Iwerks' ComiColor series.

Columbia Records issued a 1946 version on two 78 RPM records with narration by Don Lyon.[16] It was issued in a folder with artwork showing Sambo to be quite black indeed, though the narrative preserves the locale as India.[17]

In 1961, HMV Junior Record Club issued a dramatised version – words by David Croft, music by Cyril Ornadel – with Susan Hampshire in the title role and narrated by Ray Ellington.[18]

Restaurant

An independent restaurant founded in 1957 in Lincoln City, Oregon, is named Lil' Sambo's after the fictional character.[19]

Coincidentally, a popular US restaurant chain of the 1950s through 1970s, Sambo's, borrowed characters from the book (including Sambo and the tigers) for promotional purposes, although the Sambo name was originally a portmanteau of the founders' names and nicknames: Sam (Sam Battistone) and Bo (Newell Bohnett).[20] For a period in the late 1970s, some locations were renamed "The Jolly Tiger". Nonetheless, the controversy about the book led to accusations of racism that contributed to the 1,117-restaurant[21] chain's demise in the early 1980s.[20] Images inspired by the book (now considered by some racially insensitive) were common interior decorations in the restaurants.[22] Though portions of the original chain were renamed No Place Like Sam's to try to forestall closure,[21] all but the original restaurants in Santa Barbara, California, had closed by 1983. The original location still exists in Santa Barbara under the name Sambo's.[23]

See also

- List of banned books

- Zambo (or in Southern Spanish Sambo/sambo), a term used in the Spanish colonial caste system to denote a person with both African and Amerindian ancestry.

- Ethnic issues in Japan

- Murzynek Bambo – Little black Bambo by Polish writer Julian Tuwim

- Jynx

References

- ↑ "Helen Bannerman on the Train to Kodaikanal". Archived from the original on 15 May 2007. Retrieved 11 April 2007.

- ↑ Jeyathurai, Dashini (2012-04-04). "The complicated racial politics of Little Black Sambo". South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA). Retrieved 2018-08-04.

- ↑ The Story of Little Black Sambo .sterlingtimes.co.uk

- ↑ Bernstein, Robin (2011). Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights. New York: New York University Press. pp. 66–67. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ David Pilgrim, "The Picaninny Caricature," Archived 1 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia.

- ↑ "Mimi Kaplan collection, 1900 – 1920 – Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign".

- ↑ Bannerman, Helen; Wehr, Julian (1943). Little Black Sambo. Duenewald Printing Corporation. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ↑ Kazuo Mori (2005). "A Comparison of Amusingness for Japanese Children and Senior Citizens of The Story of Little Black Sambo" (PDF). Social Behavior and Personality. Society for Personality Research/Shinshu University. 33 (5): 455–466. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2013.

- ↑ https://opac.library.twcu.ac.jp/opac/repository/1/2236/KJ00004475435.pdf

- 1 2 加藤, 夏希 (Jan 2010). "差別語規制とメディア ちびくろサンボ問題を中心に" (PDF). リテラシー史研究 (in Japanese). Waseda University (3): 41–54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ↑ Golus, Carrie. "Sambo’s subtext", The University of Chicago Magazine, September–October 2010

- ↑ "Sam and the Tigers: A New Telling of Little Black Sambo". Kirkus Reviews. Kirkus Media LLC. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ↑ Kennedy, Louise (14 December 2003), "New Storybook Reopens Old Wounds", The Boston Globe

- ↑ Random House, Inc., New York, 2004. ISBN 978-0-375-82719-8.

- ↑ "Tin Toys #1".

- ↑ "Little Black Sambo, by Don Lyon (1946)".

- ↑ "Don Lyon – Little Black Sambo".

- ↑ "Various Artists – Black Sambo, Black Sambo".

- ↑ "Lil Sambos Restaurant in Lincoln city". Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Massachusetts asks ban on 'Sambo's' name". The Miami News. 27 September 1978. p. 4a.

Prosecutors say unless the name is banned, "Racial tensions will increase."

- 1 2 "Sambo's to Alter Northeast Names". The New York Times. 11 March 1981.

- ↑ "Sambo's restaurants file for voluntary bankruptcy". The Deseret News. 27 November 1981. p. 6e.

- ↑ "On This Date in Santa Barbara: Sambo's Opens". 17 June 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

Further reading

- Barbara Bader (1996). "Sambo, Babaji, and Sam", The Horn Book Magazine. September–October 1996, vol. 72, no. 5, p. 536.

- Phyllis Settecase Barton (1999). Pictus Orbis Sambo: A Publishing History, Checklist and Price Guide for The Story of Little Black Sambo (1899–1999) Centennial Collector's Guide. Pictus Orbis Press, Sun City, CA.

- Dashini Jeyathuray (2012). "The complicated racial politics of Little Black Sambo", South Asian American Digital Archive. 5 April 2012:

- Kazuo Mori (2005). "A Comparison of Amusingness for Japanese Children and Senior Citizens of The Story of Little Black Sambo in the Traditional Version and Nonracist Version." Social Behavior and Personality, Vol.33, pp.455–466.

External links

- The Story of Little Black Sambo (1923 authorized American edition) at Internet Archive.

- The Story of Little Black Sambo (illus. John R. Neill) at Internet Archive.