Lenalidomide

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌlɛnəˈlɪdoʊmaɪd/ |

| Trade names | Revlimid |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a608001 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral (capsules) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Undetermined |

| Protein binding | 30% |

| Metabolism | Undetermined |

| Elimination half-life | 3 hours |

| Excretion | Renal (67% unchanged) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.218.924 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H13N3O3 |

| Molar mass | 259.261 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

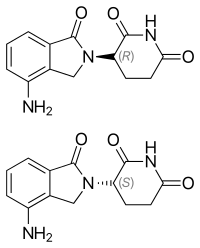

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Lenalidomide (trade name Revlimid) is a derivative of thalidomide approved in the United States in 2005.[1]

It was initially intended as a treatment for multiple myeloma, for which thalidomide is an accepted therapeutic treatment. Lenalidomide has also shown efficacy in the class of hematological disorders known as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Along with several other drugs developed in recent years, lenalidomide has significantly improved overall survival in myeloma (which formerly carried a poor prognosis), although toxicity remains an issue for users.[2] It costs $163,381 per year for the average patient.[3]

Medical uses

Multiple myeloma

Multiple myeloma is a cancer of the blood, characterized by accumulation of a plasma cell clone in the bone marrow.[4] Lenalidomide is one of the novel drug agents used to treat multiple myeloma. It is a more potent molecular analog of thalidomide, which inhibits tumor angiogenesis, tumor secreted cytokines and tumor proliferation through the induction of apoptosis.[5][6][7]

Compared to placebo, lenalidomide is effective at inducing a complete or "very good partial" response as well as improving progression-free survival. Adverse events more common in people receiving lenalidomide for myeloma were neutropenia (a decrease in the white blood cell count), deep vein thrombosis, infections, and an increased risk of other hematological malignancies.[8] The risk of second primary hematological malignancies does not outweigh the benefit of using lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.[9] It may be more difficult to mobilize stem cells for autograft in people who have received lenalidomide.[10]

On 29 June 2006, lenalidomide received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance for use in combination with dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma who have received at least one prior therapy.[11] On February 22, 2017, the FDA approved lenalidomide as standalone maintenance therapy (without dexamethasone) for patients with multiple myeloma following autologous stem cell transplant.[12]

On 23 April 2009, The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued a Final Appraisal Determination (FAD) approving lenalidomide, in combination with dexamethasone, as an option to treat patients with multiple myeloma who have received two or more prior therapies in England and Wales.[13]

On 5 June 2013 the FDA designated lenalidomide as a specialty drug requiring a specialty pharmacy distribution for "use in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) in patients whose disease has relapsed or progressed after 2 prior therapies, 1 of which included bortezomib." Revlimid is only available through a specialty pharmacy, "a restricted distribution program in conjunction with a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) due to potential for embryo-fetal risk."[14]

Myelodysplastic syndromes

With myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), the best results of lenalidomide were obtained in patients with the Chromosome 5q deletion syndrome (5q- syndrome).[15] The syndrome results from deletions in human chromosome 5 that remove three adjacent genes, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, Platelet-derived growth factor receptor B, and Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor.[16][17]

It was approved by the FDA on December 27, 2005 for patients with low or intermediate-1 risk MDS with 5q- with or without additional cytogenetic abnormalities. A completed Phase II, multi-centre, single-arm, open-label study evaluated the efficacy and safety of Revlimid monotherapy treatment for achieving haematopoietic improvement in red blood cell (RBC) transfusion dependent subjects with low- or intermediate-1-risk MDS associated with a deletion 5q cytogenetic abnormality.

63.8% of subjects had achieved RBC-transfusion independence accompanied by a median increase of 5.8 g/dL in blood Hgb concentration from baseline to the maximum value during the response period. Major cytogenetic responses were observed in 44.2% and minor cytogenetic responses were observed in 24.2% of the evaluable subjects. Improvements in bone marrow morphology were also observed. The results of this study demonstrate the efficacy of Revlimid for the treatment of subjects with Low- or Intermediate-1-risk MDS and an associated del 5 cytogenetic abnormality.[15][18][19]

Lenalidomide was approved on June 17, 2013 by the European Medicines Agency for use in low- or intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) patients who have the deletion 5q cytogenetic abnormality and no other cytogenetic abnormalities, are dependent on red blood cell transfusions, and for whom other treatment options have been found to be insufficient or inadequate.[20]

Mantle cell lymphoma

Lenalidomide is approved by FDA for mantle cell lymphoma in patients whose disease has relapsed or progressed after at least two prior therapies.[1] One of these previous therapies must have included bortezomib.

Other cancers

Lenalidomide is undergoing clinical trial as a treatment for Hodgkin's lymphoma,[21] as well as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and solid tumor cancers, such as carcinoma of the pancreas.[22] One Phase 3 clinical trial being conducted by Celgene in elderly patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia was halted in July 2013 when a disproportionate number of cancer deaths were observed during treatment with lenalidomide versus patients treated with chlorambucil.[23]

Adverse effects

Lenalidomide is related to thalidomide which is known to be teratogenic. Tests in monkeys have suggested lenalidomide is also teratogenic.[24] It therefore has the pregnancy category X and cannot be prescribed for women who are pregnant or who may become pregnant during therapy. For this reason, the drug is only available in the United States (under the brand name Revlimid) through a restricted distribution system called RevAssist. Females who may become pregnant must use at least two forms of reliable contraception during treatment and for at least four weeks after discontinuing treatment with lenalidomide.[1]

In addition to embryo-fetal toxicity, lenalidomide also carries Black Box Warnings for hematologic toxicity (including significant neutropenia and thrombocytopenia) and venous/arterial thromboembolisms.[1]

Serious potential side effects are thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, and hepatotoxicity, as well as bone marrow toxicity resulting in neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Myelosuppression is the major dose-limiting toxicity, which is contrary to experience with thalidomide.[25] Lenalidomide may also be associated with adverse effects including second primary malignancy, severe cutaneous reactions, hypersensitivity reactions, tumor lysis syndrome, tumor flare reaction, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism. [1]

Venous thromboembolism

Lenalidomide, like its parent compound thalidomide, may cause venous thromboembolism (VTE), a potentially serious complication with their use. Bennett et al. have reviewed incidents of lenalidomide-associated VTE among patients with multiple myeloma.[26] They have found that there are high rates of VTE when patients with multiple myeloma received thalidomide or lenalidomide in conjunction with dexamethasone, melphalan, or doxorubicin. When lenalidomide and dexamethasone are used to treat multiple myeloma, a median of 14% of patients had VTE (range,3-75%). In patients who took prophylaxis to treat lenalidomide-associated VTE, such as aspirin, thromboembolism rates were found to be lower than without prophylaxis, frequently lower than 10%. Clearly, thromboembolism is a serious adverse drug reaction associated with lenalidomide, as well as thalidomide. In fact, a black box warning is included in the package insert for lenalidomide, indicating that lenalidomide-dexamethasone treatment for multiple myeloma is complicated by high rates of thromboembolism.

Currently, clinical trials are under way to further test the efficacy of lenalidomide to treat multiple myeloma, and to determine how to prevent lenalidomide-associated venous thromboembolism.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome

In March 2008, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) included lenalidomide on a list of 20 prescription drugs under investigation for potential safety problems. The drug is being investigated for possibly increasing the risk of developing Stevens–Johnson syndrome, a life-threatening condition affecting the skin.[27]

FDA ongoing safety review

As of 2011, the FDA has initiated an ongoing review which will focus on clinical trials which found an increased risk of developing cancers such as acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and B-cell lymphoma,[3] though the FDA is currently advising all people to continue their treatment.[28]

Mechanism of action

Lenalidomide has been used to successfully treat both inflammatory disorders and cancers in the past 10 years. There are multiple mechanisms of action, and they can be simplified by organizing them as mechanisms of action in vitro and in vivo.[29] In vitro, lenalidomide has three main activities: direct anti-tumor effect, inhibition of angiogenesis, and immunomodulation. In vivo, lenalidomide induces tumor cell apoptosis directly and indirectly by inhibition of bone marrow stromal cell support, by anti-angiogenic and anti-osteoclastogenic effects, and by immunomodulatory activity. Lenalidomide has a broad range of activities that can be exploited to treat many hematologic and solid cancers.

On a molecular level, lenalidomide has been shown to interact with the ubiquitin E3 ligase cereblon[30] and target this enzyme to degrade the Ikaros transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3.[31] This mechanism was unexpected as it suggests that the major action of lenalidomide is to re-target the activity of an enzyme rather than block the activity of an enzyme or signaling process, and thereby represents a novel mode of drug action. A more specific implication of this mechanism is that the teratogenic and anti-neoplastic properties of lenalidomide, and perhaps other thalidomide derivatives, could be disassociated.

Research

The low level of research that continued on thalidomide, in spite of its scandalous history of teratogenicity, unexpectedly showed that the compound affected immune function. The drug was, for example, recently approved by the FDA for treatment of complications from leprosy; it has also been investigated as an adjunct for treating some malignancies. Recent research on related compounds has revealed a series of molecules which inhibit tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α).

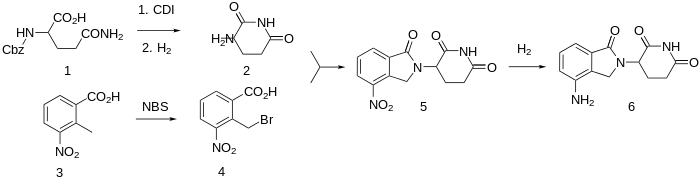

Synthesis

Price

Lenalidomide costs $163,381 per year for the average person in the United States.[3] Lenalidomide made almost $3.8bn for Celgene in 2012.[33]

In 2013 the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) rejected lenalidomide for "use in the treatment of people with a specific type of the bone marrow disorder myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)" in England and Scotland, arguing that Celgene "did not provide enough evidence to justify the £3,780 per month (USD$5746.73) price-tag of lenalidomide for use in the treatment of people with a specific type of the bone marrow disorder myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)".[33]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 REVLIMID [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2017. Accessed at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/021880s055lbl.pdf on 14 September 2018.

- ↑ McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, Hurd DD, Hassoun H, Richardson PG, Giralt S, Stadtmauer EA, Weisdorf DJ, Vij R, Moreb JS, Callander NS, Van Besien K, Gentile T, Isola L, Maziarz RT, Gabriel DA, Bashey A, Landau H, Martin T, Qazilbash MH, Levitan D, McClune B, Schlossman R, Hars V, Postiglione J, Jiang C, Bennett E, Barry S, Bressler L, Kelly M, Seiler M, Rosenbaum C, Hari P, Pasquini MC, Horowitz MM, Shea TC, Devine SM, Anderson KC, Linker C (2012). "Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma". N. Engl. J. Med. 366 (19): 1770–81. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1114083. PMC 3744390. PMID 22571201.

- 1 2 3 Badros, Ashraf Z. Badros (May 10, 2012). "Lenalidomide in Myeloma — A High-Maintenance Friend". N Engl J Med. 366 (19): 1836–1838. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1202819. PMID 22571206.

- ↑ Armoiry X, Aulagner G, Facon T (June 2008). "Lenalidomide in the treatment of multiple myeloma: a review". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 33 (3): 219–26. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00920.x. PMID 18452408.

- ↑ Li, S; Gill, N; Lentzsch, S (Nov 2010). "Recent advances of IMiDs in cancer therapy". Curr Opin Oncol. 22 (6): 579–85. doi:10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833d752c. PMID 20689431.

- ↑ Tageja, N (Mar 2011). "Lenalidomide - current understanding of mechanistic properties". Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 11 (3): 315–26. PMID 21426296.

- ↑ Kotla, V; Goel, S; Nischal, S; Heuck, C; Vivek, K; Das, B; Verma, A (Aug 2009). "Mechanism of action of lenalidomide in hematological malignancies". J Hematol Oncol. 2: 36. doi:10.1186/1756-8722-2-36. PMC 2736171. PMID 19674465.

- ↑ Yang, B; Yu, RL; Chi, XH; Lu, XC (2013). "Lenalidomide treatment for multiple myeloma: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e64354. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064354. PMC 3653900. PMID 23691202.

- ↑ Dimopoulos, MA; Richardson, PG; Brandenburg, N; Yu, Z; Weber, DM; Niesvizky, R; Morgan, GJ (Mar 22, 2012). "A review of second primary malignancy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide". Blood. 119 (12): 2764–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-08-373514. PMID 22323483.

- ↑ Li, Shirong; Gill, Navkiranjit; Lentzsch, Suzanne (November 2010). "Recent advances of IMiDs in cancer therapy". Current Opinion in Oncology. 22 (6): 579–585. doi:10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833d752c. PMID 20689431.

- ↑ "FDA approves lenalidomide oral capsules (Revlimid) for use in combination with dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma". FDA. 2006-06-29. Retrieved 2015-10-15.

- ↑ https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm542791.htm

- ↑ "REVLIMID Receives Positive Final Appraisal Determination from National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) for Use in the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Wales". Reuters. April 23, 2009.

- ↑ Ness, Stacey (13 March 2014). "New Specialty Drugs". Pharmacy Times. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- 1 2 List A, Kurtin S, Roe DJ, et al. (February 2005). "Efficacy of lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (6): 549–57. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041668. PMID 15703420.

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/5159

- ↑ Nimer SD (2006). "Clinical management of myelodysplastic syndromes with interstitial deletion of chromosome 5q". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 24 (16): 2576–82. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6715. PMID 16735711.

- ↑ List AF (August 2005). "Emerging data on IMiDs in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)". Seminars in Oncology. 32 (4 Suppl 5): S31–5. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.06.020. PMID 16085015.

- ↑ List A, Dewald G, Bennett J, et al. (October 2006). "Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion". The New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (14): 1456–65. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061292. PMID 17021321.

- ↑ "Revlimid Approved In Europe For Use In Myelodysplastic Syndromes". The MDS Beacon. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ "Phase II Study of Lenalidomide for the Treatment of Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin's Lymphoma". ClinicalTrials.gov. US National Institutes of Health. February 2009.

- ↑ "276 current clinical trials world-wide, both recruiting and fully enrolled, as of 27 February 2009". ClinicalTrials.gov. US National Institutes of Health. February 2009.

- ↑ "Celgene Discontinues Phase 3 Revlimid Study after 'Imbalance' of Deaths". Nasdaq. July 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Revlimid Summary of Product Characteristics. Annex I" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2012. p. 6.

- ↑ Rao KV (September 2007). "Lenalidomide in the treatment of multiple myeloma". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 64 (17): 1799–807. doi:10.2146/ajhp070029. PMID 17724360.

- ↑ Bennett CL, Angelotta C, Yarnold PR, et al. (December 2006). "Thalidomide- and lenalidomide-associated thromboembolism among patients with cancer". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 296 (21): 2558–60. doi:10.1001/jama.296.21.2558-c. PMID 17148721.

- ↑ "Potential Signals of Serious Risks/New Safety Information Identified from the Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) between January - March 2008". US Department of Health & Human Services. FDA. March 2008.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Ongoing safety review of Revlimid (lenalidomide) and possible increased risk of developing new malignancies". US Food and Drug Administration. FDA. April 2011.

- ↑ Vallet S, Palumbo A, Raje N, Boccadoro M, Anderson KC (July 2008). "Thalidomide and lenalidomide: Mechanism-based potential drug combinations". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 49 (7): 1238–45. doi:10.1080/10428190802005191. PMID 18452080.

- ↑ Zhu, Y. X.; Braggio, E; Shi, C. X.; Bruins, L. A.; Schmidt, J. E.; Van Wier, S; Chang, X. B.; Bjorklund, C. C.; Fonseca, R; Bergsagel, P. L.; Orlowski, R. Z.; Stewart, A. K. (2011). "Cereblon expression is required for the antimyeloma activity of lenalidomide and pomalidomide". Blood. 118 (18): 4771–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-05-356063. PMC 3208291. PMID 21860026.

- ↑ Stewart, A. K. (2014). "Medicine. How thalidomide works against cancer". Science. 343 (6168): 256–7. doi:10.1126/science.1249543. PMC 4084783. PMID 24436409.

- ↑ Muller, G. W.; Chen, R.; Huang, S. Y.; Corral, L. G.; Wong, L. M.; Patterson, R. T.; Chen, Y.; Kaplan, G.; Stirling, D. I. (1999). "Amino-substituted thalidomide analogs: Potent inhibitors of TNF-α production". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 9 (11): 1625–30. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(99)00250-4. PMID 10386948.

- 1 2 "Revlimid faces NICE rejection for use in rare blood cancer Watchdog's draft guidance does not recommend Celgene's drug for NHS use in England and Wales". Pharma News. 11 July 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

Further reading

- Chang DH, Liu N, Klimek V, et al. (July 2006). "Enhancement of ligand-dependent activation of human natural killer T cells by lenalidomide: therapeutic implications". Blood. 108 (2): 618–21. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-10-4184. PMC 1895497. PMID 16569772.

- Anderson KC (October 2005). "Lenalidomide and thalidomide: mechanisms of action--similarities and differences". Seminars in Hematology. 42 (4 Suppl 4): S3–8. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2005.10.001. PMID 16344099.

External links

- Official website Includes list of adverse reactions

- Prescribing Information

- International Myeloma Foundation article on Revlimid

- multiplemyeloma.org Revlimid April 2007 Summary