Laurence Sterne

| Laurence Sterne | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Laurence Sterne by Joshua Reynolds, 1760 | |

| Born |

24 November 1713 Clonmel, County Tipperary, Kingdom of Ireland |

| Died |

18 March 1768 (aged 54) London, England |

| Occupation | Novelist, clergyman |

| Nationality | Anglo-Irish |

| Alma mater | Jesus College, Cambridge |

| Notable works |

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy A Political Romance |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Lumley |

Laurence Sterne (24 November 1713 – 18 March 1768) was an Irish-born English novelist and an Anglican clergyman. He wrote the novels The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman and A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, and also published many sermons, wrote memoirs, and was involved in local politics. Sterne died in London after years of fighting tuberculosis.

Early life and education

Sterne was born in Clonmel, County Tipperary. His father, Roger Sterne, was an ensign in a British regiment recently returned from Dunkirk, which was disbanded on the day of Sterne's birth. Within six months the family had returned to Yorkshire, and in July 1715 they moved back to Ireland, having "decamped with Bag & Baggage for Dublin", in Sterne's words.[1]

The first decade of Sterne's life was spent moving from place to place as his father was reassigned throughout Ireland. During this period Sterne never lived in one place for more than a year. In addition to Clonmel and Dublin, his family also lived in, among other places, Wicklow Town, Annamoe (County Wicklow), Drogheda (County Louth), Castlepollard (County Westmeath), and Carrickfergus (County Antrim).[2] In 1724, his father took Sterne to Roger's wealthy brother, Richard, so that Sterne could attend Hipperholme Grammar School near Halifax; Sterne never saw his father again as Roger was ordered to Jamaica where he died of a fever in 1731. Sterne was admitted to a sizarship at Jesus College, Cambridge, in July 1733 at the age of 20.[3] His great-grandfather Richard Sterne had been the Master of the college as well as the Archbishop of York. Sterne graduated with a degree of Bachelor of Arts in January 1737; and returned in the summer of 1740 to be awarded his Master of Arts degree.[3]

Early career

Sterne was ordained as a deacon in March 1737 and as a priest in August 1738. His religion is said to have been the "centrist Anglicanism of his time," known as 'latitudinarianism."[4] Shortly thereafter Sterne was awarded the vicarship living of Sutton-on-the-Forest in Yorkshire. Sterne married Elizabeth Lumley in 1741. Both were ill with consumption. In 1743, he was presented to the neighbouring living of Stillington by Rev. Richard Levett, Prebendary of Stillington, who was patron of the living.[5] Subsequently Sterne did duty both there and at Sutton. He was also a prebendary of York Minster. Sterne's life at this time was closely tied with his uncle, Dr Jaques Sterne, the Archdeacon of Cleveland and Precentor of York Minster. Sterne's uncle was an ardent Whig, and urged Sterne to begin a career of political journalism which resulted in some scandal for Sterne and, eventually, a terminal falling-out between the two men.

Jaques Sterne was a powerful clergyman but a mean-tempered man and a rabid politician. In 1741–42 Sterne wrote political articles supporting the administration of Sir Robert Walpole for a newspaper founded by his uncle but soon withdrew from politics in disgust. His uncle became his arch-enemy, thwarting his advancement whenever possible.

Sterne lived in Sutton for twenty years, during which time he kept up an intimacy which had begun at Cambridge with John Hall-Stevenson, a witty and accomplished bon vivant, owner of Skelton Hall in the Cleveland district of Yorkshire.

Writing

In 1759, to support his dean in a church squabble, Sterne wrote A Political Romance (later called The History of a Good Warm Watch-Coat), a Swiftian satire of dignitaries of the spiritual courts. At the demands of embarrassed churchmen, the book was burnt. Thus, Sterne lost his chances for clerical advancement but discovered his real talents; until the completion of this first work, "he hardly knew that he could write at all, much less with humour so as to make his reader laugh".[6]

Having discovered his talent, at the age of 46, he turned over his parishes to a curate, and dedicated himself to writing for the rest of his life. It was while living in the countryside, having failed in his attempts to supplement his income as a farmer and struggling with tuberculosis, that Sterne began work on his best known novel, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, the first volumes of which were published in 1759. Sterne was at work on his celebrated comic novel during the year that his mother died, his wife was seriously ill, and his daughter was also taken ill with a fever.[7] He wrote as fast as he possibly could, composing the first 18 chapters between January and March 1759.[6]

An initial, sharply satiric version was rejected by Robert Dodsley, the London printer, just when Sterne's personal life was upset. His mother and uncle both died. His wife had a nervous breakdown and threatened suicide. Sterne continued his comic novel, but every sentence, he said, was "written under the greatest heaviness of heart." In this mood, he softened the satire and recounted details of Tristram's opinions, eccentric family and ill-fated childhood with a sympathetic humour, sometimes hilarious, sometimes sweetly melancholic—a comedy skirting tragedy.

The publication of Tristram Shandy made Sterne famous in London and on the continent. He was delighted by the attention, famously saying "I wrote not [to] be fed but to be famous."[8] He spent part of each year in London, being fêted as new volumes appeared. Even after the publication of volumes three and four of Tristram Shandy, his love of attention (especially as related to financial success) remained undiminished. In one letter, he wrote "One half of the town abuse my book as bitterly, as the other half cry it up to the skies—the best is, they abuse it and buy it, and at such a rate, that we are going on with a second edition, as fast as possible."[9] Indeed, Baron Fauconberg rewarded Sterne by appointing him as the perpetual curate of Coxwold, North Yorkshire.

Foreign travel

Sterne continued to struggle with his illness, and departed England for France in 1762 in an effort to find a climate that would alleviate his suffering. Sterne was lucky to attach himself to a diplomatic party bound for Turin, as England and France were still adversaries in the Seven Years' War. Sterne was gratified by his reception in France where reports of the genius of Tristram Shandy had made him a celebrity. Aspects of this trip to France were incorporated into Sterne's second novel, A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy.

Eliza

Early in 1767 Sterne met Eliza Draper, the wife of an official of the East India Company, then staying on her own in London. He was quickly captivated by Eliza’s charm, vivacity and intelligence, and she did little to discourage the attentions of such a celebrated man. They met frequently, exchanged miniature portraits, and Sterne’s admiration seems to have turned into an obsession which he took no trouble to conceal. To his great distress Eliza had to return to India three months after their first meeting, and he died from consumption a year later without seeing her again. At the beginning of 1768, Sterne brought out his Sentimental Journey which contains some extravagant references to her, and the relationship, though platonic, aroused considerable interest. He also wrote his Journal to Eliza part of which he sent to her, and the rest of which came to light when it was presented to the British Museum in 1894. After Sterne’s death Eliza allowed ten of his letters to be published under the title Letters from Yorick to Eliza and succeeded in suppressing her letters to him, though some blatant forgeries were produced, probably by William Combe, in a volume entitled Eliza’s Letters to Yorick.[10]

Death and "resurrection"

Less than a month after Sentimental Journey was published, early in 1768, Sterne's strength failed him, and he died in his lodgings at 41 Old Bond Street on 18 March, at the age of 54. He was buried in the churchyard of St George's, Hanover Square.

It was widely rumoured that Sterne's body was stolen shortly after it was interred and sold to anatomists at Cambridge University. Circumstantially, it was said that his body was recognised by Charles Collignon who knew him[11] and discreetly reinterred back in St George's, in an unknown plot. A year later a group of Freemasons erected a memorial stone with a rhyming epitaph near to his original burial place. A second stone was erected in 1893, correcting some factual errors on the memorial stone. When the churchyard of St. George's was redeveloped in 1969, amongst 11,500 skulls disinterred, several were identified with drastic cuts from anatomising or a post-mortem examination. One was identified to be of a size that matched a bust of Sterne made by Nollekens.[12]

The skull was held up to be his, albeit with "a certain area of doubt". Along with nearby skeletal bones, these remains were transferred to Coxwold churchyard in 1969 by the Laurence Sterne Trust.[13]

The story of the reinterment of Sterne's skull in Coxwold is alluded to in Malcolm Bradbury's novel To The Hermitage.

Works

Sterne's early works were letters; he had two ordinary sermons published (in 1747 and 1750), and tried his hand at satire. He was involved in, and wrote about, local politics in 1742. His major publication prior to Tristram Shandy was the satire A Political Romance (1759), aimed at conflicts of interest within York Minster. A posthumously published piece on the art of preaching, A Fragment in the Manner of Rabelais, appears to have been written in 1759. Rabelais was by far Sterne's favourite author, and in his correspondence he made clear that he considered himself as Rabelais' successor in humour writing, distancing himself from Jonathan Swift:[14][15]

I ... deny I have gone as far as Swift: he keeps a due distance from Rabelais; I keep a due distance from him.

Sterne's novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman sold widely in England and throughout Europe. Translations of the work began to appear in all the major European languages almost upon its publication, and Sterne influenced European writers as diverse as Denis Diderot and the German Romanticists. His work had also noticeable influence over Brazilian author Machado de Assis, who made use of the digressive technique in the novel The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas. Tristram Shandy, in which Sterne manipulates narrative time and voice, parodies accepted narrative form, and includes a healthy dose of bawdy humour, was largely dismissed in England as being too corrupt. Samuel Johnson's verdict in 1776 was that "Nothing odd will do long. Tristram Shandy did not last."[16]

This is strikingly different from the views of European critics of the day, who praised Sterne and Tristram Shandy as innovative and superior. Voltaire called it "clearly superior to Rabelais", and later Goethe praised Sterne as "the most beautiful spirit that ever lived." Both during his life and for a long time after, efforts were made by many to reclaim Sterne as an arch-sentimentalist; parts of Tristram Shandy, such as the tale of Le Fever, were excerpted and published separately to wide acclaim from the moralists of the day. The success of the novel and its serialised nature also allowed many imitators to publish pamphlets concerning the Shandean characters and other Shandean-related material even while the novel was yet unfinished.

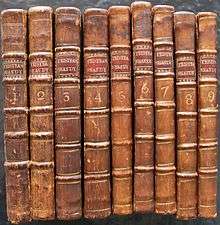

The novel itself starts with the narration, by Tristram, of his own conception. It proceeds by fits and starts, but mostly by what Sterne calls "progressive digressions" so that we do not reach Tristram's birth before the third volume. The novel is rich in characters and humour, and the influences of Rabelais and Miguel de Cervantes are present throughout. The novel ends after 9 volumes, published over a decade, but without anything that might be considered a traditional conclusion. Sterne inserts sermons, essays and legal documents into the pages of his novel; and he explores the limits of typography and print design by including marbled pages and an entirely black page within the narrative. Many of the innovations that Sterne introduced, adaptations in form that were an exploration of what constitutes the novel, were highly influential to Modernist writers like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, and more contemporary writers such as Thomas Pynchon and David Foster Wallace. Italo Calvino referred to Tristram Shandy as the "undoubted progenitor of all avant-garde novels of our century". The Russian Formalist writer Viktor Shklovsky regarded Tristram Shandy as the archetypal, quintessential novel, of which all other novels are mere subsets: "Tristram Shandy is the most typical novel of world literature."[17]

However, the leading critical opinions of Tristram Shandy tend to be markedly polarised in their evaluations of its significance. Since the 1950s, following the lead of DW Jefferson, there are those who argue that, whatever its legacy of influence may be, Tristram Shandy in its original context actually represents a resurgence of a much older, Renaissance tradition of "Learned Wit" – owing a debt to such influences as the Scriblerian approach.

A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy is a less influential book, although it was better received by English critics of the day. The book has many stylistic parallels with Tristram Shandy, and indeed, the narrator is one of the minor characters from the earlier novel. Although the story is more straightforward, A Sentimental Journey can be understood to be part of the same artistic project to which Tristram Shandy belongs.

Two volumes of Sterne's Sermons were published during his lifetime; more copies of his Sermons were sold in his lifetime than copies of Tristram Shandy, and for a while he was better known in some circles as a preacher than as a novelist. The sermons, though, are conventional in both style and substance. Several volumes of letters were published after his death, as was Journal to Eliza, a more sentimental than humorous love letter to a woman Sterne was courting during the final years of his life. Compared to many eighteenth-century authors, Sterne's body of work is quite small.

Abolitionists

In 1766, at the height of the debate about slavery, the composer and former slave Ignatius Sancho wrote to Sterne[18] encouraging him to use his pen to lobby for the abolition of the slave trade.[19]

That subject, handled in your striking manner, would ease the yoke (perhaps) of many—but if only one—Gracious God!—what a feast to a benevolent heart!

In July 1766 Sterne received Sancho's letter shortly after he had finished writing a conversation between his fictional characters Corporal Trim and his brother Tom in Tristram Shandy, wherein Tom described the oppression of a black servant in a sausage shop in Lisbon which he had visited.[20] Sterne's widely publicised response to Sancho's letter became an integral part of 18th-century abolitionist literature:

There is a strange coincidence, Sancho, in the little events (as well as in the great ones) of this world: for I had been writing a tender tale of the sorrows of a friendless poor negro-girl, and my eyes had scarce done smarting with it, when your letter of recommendation in behalf of so many of her brethren and sisters, came to me—but why her brethren?—or your’s, Sancho! any more than mine? It is by the finest tints, and most insensible gradations, that nature descends from the fairest face about St. James’s, to the sootiest complexion in Africa: at which tint of these, is it, that the ties of blood are to cease? and how many shades must we descend lower still in the scale, ’ere mercy is to vanish with them?—but ’tis no uncommon thing, my good Sancho, for one half of the world to use the other half of it like brutes, & then endeavor to make ’em so.|Laurence Sterne, 27 July 1766[20]

Bibliography

His works, first collected in 1779, were edited, with newly discovered letters, by JP Browne (London, 1873). A less complete edition was edited by G Saintsbury (London, 1894). The Florida Edition of Sterne's works is currently the leading scholarly edition – although the final volume (Sterne's letters) has yet to be published.

- René Bosch, Labyrinth of Digressions: Tristram Shandy as Perceived and Influenced by Sterne's Early Imitators (Amsterdam, 2007)

- W. M. Thackeray, in English Humourists of the Eighteenth Century (London, 1853; new edition, New York, 1911)

- Percy Fitzgerald, Life of Laurence Sterne (London, 1864; second edition, London, 1896)

- Paul Stapfer, Laurence Sterne, sa personne et ses ouvrages (second edition, Paris, 1882)

- H. D. Traill, Laurence Sterne, "English Men of Letters", (London, 1882)[21]

- Texte, Rousseau et le cosmopolitisme littôraire au XVIIIème siècle (Paris, 1895)

- H. W. Thayer, Laurence Sterne in Germany (New York, 1905)

- P. E. More, Shelburne Essays (third series, New York, 1905)

- Wilbur Lucius Cross [1908] Life and Times of Sterne, New York 1909[22]

- W. S. Sichel, Sterne; A Study (New York, 1910)

- L. S. Benjamin, Life and Letters (two volumes, 1912)

- Arthur Cash, Laurence Sterne: The Early and Middle Years ( ISBN 0-416-82210-X, 1975) and Laurence Sterne: The Later Years ( ISBN 0-416-32930-6, 1986)

- Rousseau, George S. (2004). Nervous Acts: Essays on Literature, Culture and Sensibility. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-3454-1

- D. W. Jefferson, "Tristram Shandy and the Tradition of Learned Wit" in Essays in Criticism, 1(1951), 225–48.

- Ryan J. Stark, "Tristram Shandy and the Devil," in Theology and Literature in the Age of Johnson, ed. Melvyn New and Gerard Reedy (University of Delaware Press, 2012), 203–18.

- Lynch, J. Tristram Shandy: An Annotated Bibliography [17]

- The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Vol. 10. The Age of Johnson. III. Sterne, and the Novel of His Times. Bibliography.[23]

- Bibliography for the study of Laurence Sterne[24]

- Articles on Laurence Sterne.[25]

See also

References

- ↑ Barfoot, C.C. and Theo D'haen The Clash of Ireland: Literary Contrasts and Connections. Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi, 1989. 49.

- ↑ Barfoot, C.C. and Theo D'haen The Clash of Ireland: Literary Contrasts and Connections. Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi, 1989. 48–51; Cash, Arthur. Laurence Sterne: The Early and Middle Years. London: Methuen, 1975. 2–22.

- 1 2 "Laurence Sterne (STN733L)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ "Laurence Sterne". www.oxforddnb.com. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- ↑ Cross (1908), chap. 2 Marriage and Settlement at Sutton-on-the-Forest, p.53

- 1 2 Cross (1908), chap. 8, The Publication of Tristram Shandy: Volumes I and II, p.178

- ↑ "Cross (1908), chap. 8, The Publication of Tristram Shandy: Volumes I and II, p.197

- ↑ Fanning, Christopher. "Sterne and print culture". The Cambridge Companion to Laurence Sterne: 125–141.

- ↑ The Letters of Laurence Sterne: Part One, 1739–1764. University Press of Florida. 2009. pp. 129–130. ISBN 9780813032368.

- ↑ Sclater, , William Lutley (1922). Sterne's Eliza; some account of her life in India: with her letters written between 1757 and 1774. London: W. Heinemann. p. 45-58.

- ↑ Arnold, Catherine (2008). Necropolis: London and Its Dead - Google Books Result. p. contents. ISBN 1847394930. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ "Is this the skull of Sterne?". The Times. 5 June 1969.

- ↑ Alas, Poor Yorick, Letters, The Times, 16 June 1969, Kenneth Monkman, Laurence Sterne Trust. "If we have reburied the wrong one, nobody, I feel beyond reasonable doubt, would enjoy the situation more than Sterne"

- ↑ Brown, Huntington (1967) Rabelais in English literature pp.190–1

- ↑ Cross (1908), chap. 8, The Publication of Tristram Shandy: Volumes I and II, p.179

- ↑ James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson…, ed. Malone, vol. II (London: 1824) p. 422.

- 1 2 "Lynch, Tristram Shandy Bibliography". andromeda.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ Carey, Brycchan (March 2003). "The extraordinary Negro': Ignatius Sancho, Joseph Jekyll, and the Problem of Biography" (PDF). Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies. 26 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1754-0208.2003.tb00257.x. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ↑ Phillips, Caryl (December 1996). "Director's Forward". Ignatius Sancho: an African Man of Letters. London: National Portrait Gallery. p. 12.

- 1 2 "Ignatius Sancho and Laurence Sterne" (PDF). Norton.

- ↑ H. D. Traill. "Sterne". Harper & Brothers Publishers. Retrieved 22 March 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Cross, Wilbur L. (Wilbur Lucius) (22 March 2018). "The life and times of Laurence Sterne". New York : Macmillan. Retrieved 22 March 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ "III. Sterne, and the Novel of His Times: Bibliography. Vol. 10. The Age of Johnson. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature: An Encyclopedia in Eighteen Volumes. 1907–21". www.bartleby.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Bibliography for the study of Laurence Sterne". post.queensu.ca. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Useful Articles on Laurence Sterne". post.queensu.ca. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Laurence Sterne. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Laurence Sterne |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Laurence Sterne |

- Works by Laurence Sterne at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Laurence Sterne at Internet Archive

- Works by Laurence Sterne at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Tristram Shandy (beta) In Our Time - Radio 4 - BBC

- Laurence Sterne at the Google Books Search

- Laurence Sterne at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- "Tristram Shandy". Annotated, with bibliography, criticism.

- Ron Schuler's Parlour Tricks: The Scrapbook Mind of Laurence Sterne

- The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy & A Sentimental Journey. Munich: Edited by Günter Jürgensmeier, 2005

- The Shandean: A Journal Devoted to the Works of Laurence Sterne (tables of contents available online)

- Laurence Sterne at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- The Laurence Sterne Trust