Laurier Palace Theatre fire

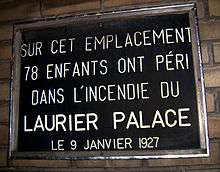

The Laurier Palace Theatre fire, sometimes known as the Saddest fire or the Laurier Palace Theatre crush, was a fire that occurred in a movie theatre in Montreal, Quebec, Canada on Sunday, January 9, 1927. 78 people died in the ensuing mayhem.[1][2] The theatre was located at 3215 Saint Catherine Street East, just east of Dézéry St.

The fire

The fire — reportedly caused by a discarded cigarette smoldering beneath wooden floorboards — started in the early afternoon during a comedy called Get 'Em Young.[3] 800 children came to watch, and panic erupted when smoke began to billow into the theater.

The children — who were seated in the balcony — had trouble exiting the building, as one of two stairways that led to safety was blocked. Further, the exit doors opened inwards, meaning that the crush of children trying to escape had the effect of closing the doors more tightly, rather than opening them. The projectionist, Emile Massicotte, dragged about 30 children from the locked exit into the fireproof projection booth, then passed them out a window onto the marquee above the sidewalk, whence they descended fireman's ladders to the street. One usher, Paul Champagne, remained on duty to help direct evacuation at the other stairway that was not blocked; he and Massicotte were credited with preventing the toll from being much higher.

Smoke filled the air, choking and blinding the children within two minutes. Survivors remembered a cry of "Au feu! Au feu!" (A fire! A fire!) and everybody began to try to rush out, but ushers blocked the east balcony exit and yelled; "No danger. No danger. Go back to your seats!" before they were pushed aside.[4]

Firefighters arrived rapidly from Fire Station Number 13 just across the street (50 yards)[5], but not fast enough to prevent the deaths of 78 children.[6] Of the dead 12 were crushed and 64 asphyxiated; only 2 children actually died from the fire itself. The first firefighter to enter the building, Alphéa Arpin, discovered his own son, Gaston, aged 6, in the pile of bodies. Another man, Adélard Boisseau, discovered one of his 3 children. He would identify the bodies of his two other children later that evening at the morgue.

Aftermath

On January 11, funeral services were held in l'Église de la Nativité (the Church of the Nativity), near the theatre, for 39 of the victims. More than 50,000 watched the funeral procession. During the homily, Father Georges Gauthier, co-archbishop of Montréal, asked "why, on the Lord's day, are places of pleasure such as the one that just burned down allowed to remain open?" ("pourquoi on laisse ouverts en ce jour (celui du Seigneur) des lieux de plaisir comme celui-ci qui vient d'être incendié?"). He stated concern about the moral safety ("sécurité morale") of children. He asked whether it was too rash to ask if, in this province, one could find souls great enough and impartial enough to write laws barring children from the cinema.

There are a large number of songs based around the fire with the Singer Hercule Lavoie singing about the fire with the words:

«Il fallait des anges au paradis

Des chérubins aux blondes têtes

Et c’est pourquoi Dieu vous a pris

Votre bambin, votre fillette,

Consolez-vous, séchez vos pleurs

Ils sont heureux dans un monde meilleur

Il fallait des anges au paradis

C’est votre enfant que le Ciel a choisi.»[7]

Political

The people seized upon the tragedy of the Laurier Palace Theatre as an opportunity to block children's access to the cinema in general, claiming that the cinema "ruins the health of children, weakens their lungs, troubles their imagination, excites their nervous system, harms their education, overexcites their sinful ideas and leads to immorality" ("ruine la santé des enfants, affaiblit leurs poumons, affole leur imagination, excite leur système nerveux, nuit à leurs études, surexcite les désirs mauvais et conduit à l'immoralité").

A few months later Judge Louis Boyer recommended that everyone under 16 be forbidden access to cinema screenings. The following year, to appease extremists who wanted the cinema closed to all, such a law was passed[8] and remained in effect for 33 years, until 1961. Building codes were also modified so that the doors of public buildings were required to open outwards.

In 1967 the cinema law was further modified, setting up a motion picture rating system that divided the movie-going population into age groups of 18 and over, 14 and over, and general (for all).

Litigation

The owner of the theater, Ameen Lawand was at his other theater the day of the fire, and immediately called his lawyer when he heard about the fire.

Inquiry

After the official inquiry there was never a released official cause for the fire, with Lawand and his employees claiming the children in the theater were always lighting matches to see under the seats. Others believed that there was faulty wiring to blame for the fire.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ "Three Held to Answer for 78 Panic Deaths". The Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 2 November 2015 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ↑ "Erez resize". banq.qc.ca. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ "Tragic Movie Fire Kills 77 Children". The Evening Independent. St. Petersburg, Florida. January 10, 1927. pp. 1, 7.

- ↑ Bell, Don (August 21, 1982). "A survivor remembers cinema fire that killed 78; Olivier Racette was the last youngster to make it alive out of the Laurier Palace Theatre". The GAZETTE Montreal. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- 1 2 "The Laurier Palace Theatre Fire". Silent Toronto. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- ↑ Fahrni, Magda (Fall 2015). "Glimpsing Working-Class Childhood through the Laurier Palace Fire of 1927: The Ordinary, the Tragic, and the Historians Gaze". The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth. 8: 426–450.

- ↑ Proulx, Gilles. "L'hécatombe du Laurier-Palace (1927)". Le Journal de Montréal (in French). Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- ↑ "Our Local Hollywood Connections - Stan Laurel, Snow White and Quebec Cinema Laws", Montreal Mosaic. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- "Seventy-Six Children Killed in Panic on Stairway at Fire in East St. Catherine Street Movie Theatre Sunday Afternoon", Montreal Gazette, January 10, 1927, p1

- Schmidt, René. Canadian Disasters.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070204031528/http://www.bitesizecanada.org/quebec.htm

- http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1SEC900557%5Bdead+link%5D

Coordinates: 45°32′22″N 73°32′27″W / 45.53944°N 73.54083°W