Koh-i-Noor

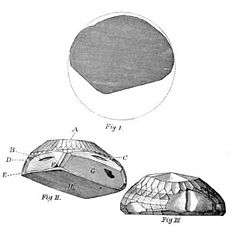

Glass replicas of the diamond before (upside down) and after it was re-cut in 1852 | |

| |

| Weight | 105.602 carats (21.1204 g)[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|

| Dimensions |

3.6 cm (1.4 in) long 3.2 cm (1.3 in) wide 1.3 cm (0.5 in) deep |

| Colour | D (colourless)[4] |

| Type | IIa[4] |

| Cut | Oval brilliant |

| Facets | 66[5] |

| Country of origin | India |

| Mine of origin | Kollur Mine |

| Cut by | Levie Benjamin Voorzanger |

| Owner | Queen Elizabeth II in right of the Crown[6] |

| Estimated value | Not insured[7] |

The Koh-i-Noor (/ˌkoʊɪˈnʊər/;[8] Persian: کوهِ نور), also spelt Kohinoor and Koh-i-Nur, is one of the largest cut diamonds in the world, weighing 105.6 carats (21.12 g),[lower-alpha 1] and part of the British Crown Jewels.

The diamond was originally owned by the Kakatiya dynasty.[9] Probably mined in Golconda, India, there is no record of its original weight, but the earliest well-attested weight is 186 old carats (191 metric carats or 38.2 g). Koh-i-Noor is Persian for "Mountain of Light"; it has been known by this name since the 18th century. It changed hands between various factions in modern-day India, Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan, until being ceded to Queen Victoria after the British conquest of the Punjab in 1849.

Originally, the stone was of a similar cut to other Mughal era diamonds which are now in the Iranian Crown Jewels. In 1851, it went on display at the Great Exhibition in London, but the lacklustre cut failed to impress viewers. Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, ordered it to be re-cut as an oval brilliant by Coster Diamonds. By modern standards, the culet is unusually broad, giving the impression of a black hole when the stone is viewed head-on; it is nevertheless regarded by gemmologists as "full of life".[10]

Because its history involves a great deal of fighting between men, the Koh-i-Noor acquired a reputation within the British royal family for bringing bad luck to any man who wears it. Since arriving in the UK, it has only been worn by female members of the family.[11] Victoria wore the stone in a brooch and a circlet. After she died in 1901, it was set in the Crown of Queen Alexandra, wife of Edward VII. It was transferred to the Crown of Queen Mary in 1911, and finally to the Crown of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother in 1937.

Today, the diamond is on public display in the Jewel House at the Tower of London, where it is seen by millions of visitors each year. The governments of India, Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan have all claimed rightful ownership of the Koh-i-Noor and demanded its return ever since India gained independence from the UK in 1947. The British government insists the gem was obtained legally under the terms of the Last Treaty of Lahore and has rejected the claims.

History

Origin

The diamond is widely believed to have come from Kollur Mine,[12][13] a series of 4-metre (13 ft) deep gravel-clay pits on the banks of Krishna River in the Golconda (present-day Andhra Pradesh), India.[14] It is impossible to know exactly when or where it was found, and many unverifiable theories exist as to its original owner.[15]

Early history

Babur, the Turco-Mongol founder of the Mughal Empire, wrote about a "famous" diamond that weighed just over 187 old carats – approximately the size of the 186-carat Koh-i-Noor.[16] Some historians think Babur's diamond is the earliest reliable reference to the Koh-i-Noor.[17] According to his diary, it was acquired by Alauddin Khalji, second ruler of the Khalji dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate, when he invaded the kingdoms of southern India at the beginning of the 14th century. It later passed to succeeding dynasties of the Sultanate, and Babur received the diamond in 1526 as a tribute for his conquest of Delhi and Agra at the Battle of Panipat.[15]

Shah Jahan, the fifth Mughal emperor, had the stone placed into his ornate Peacock Throne. In 1658, his son and successor, Aurangzeb, confined the ailing emperor to Agra Fort. While in the possession of Aurangzeb, it was allegedly cut by Hortenso Borgia, a Venetian lapidary, reducing the weight of the large stone to 186 carats (37.2 g).[18] For this carelessness, Borgia was reprimanded and fined 10,000 rupees.[19] According to recent research the story of Borgia cutting the diamond is not correct, and most probably mixed up with the Orlov, part of Catherine the Great's imperial Russian sceptre in the Kremlin.[20]

Following the 1739 invasion of Delhi by Nader Shah, the Afsharid Shah of Persia, the treasury of the Mughal Empire was looted by his army in an organised and thorough acquisition of the Mughal nobility's wealth.[22] Along with millions of rupees and an assortment of historic jewels, the Shah also carried away the Koh-i-Noor.[23] He exclaimed Koh-i-Noor!, Persian for "Mountain of Light", when he obtained the famous stone.[24] One of his consorts said, "If a strong man were to throw four stones – one north, one south, one east, one west, and a fifth stone up into the air – and if the space between them were to be filled with gold, all would not equal the value of the Koh-i-Noor".[25]

After Nader Shah was killed and his empire collapsed in 1747, the Koh-i-Noor fell to his grandson, who in 1751 gave it to Ahmad Shah Durrani, founder of the Afghan Empire, in return for his support.[23] One of Ahmed's descendants, Shuja Shah Durrani, wore a bracelet containing the Koh-i-Noor on the occasion of Mountstuart Elphinstone's visit to Peshawar in 1808.[26] A year later, Shujah formed an alliance with the United Kingdom to help defend against a possible invasion of Afghanistan by Russia.[27] He was quickly overthrown, but fled with the diamond to Lahore, where Ranjit Singh, founder of the Sikh Empire, in return for his hospitality, insisted upon the gem being given to him, and he took possession of it in 1813.[22]

Acquisition by Queen Victoria

Its new owner, Ranjit Singh, willed the diamond to the East India Company administered Hindu Jagannath Temple in Puri, in modern-day Odisha, India.[28] However, after his death in 1839, his will was not executed.[29] On 29 March 1849, following the conclusion of the Second Anglo-Sikh War, the Kingdom of Punjab was formally annexed to Company rule, and the Last Treaty of Lahore was signed, officially ceding the Koh-i-Noor to Queen Victoria and the Maharaja's other assets to the company. Article III of the treaty read: "The gem called the Koh-i-Noor, which was taken from Shah Sooja-ool-moolk by Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, shall be surrendered by the Maharajah of Lahore to the Queen of England (sic)".[30]

The Governor-General in charge of the ratification of this treaty was the Marquess of Dalhousie. The manner of his aiding in the transfer of the diamond was criticized even by some of his contemporaries in Britain. Although some thought it should have been presented as a gift to Queen Victoria by the East India Company, it is clear that Dalhousie believed the stone was a spoil of war, and treated it accordingly, ensuring that it was officially surrendered to her by Duleep Singh, the youngest son of Ranjit Singh.[31] The presentation of the Koh-i-Noor by the East India Company to the queen was the latest in a long history of transfers of the diamond as a coveted spoil of war.[32] Duleep Singh had been placed in the guardianship of Dr John Login, a surgeon in the British Army serving in the Presidency of Bengal. Duleep Singh would move to England in 1854.

Journey to the United Kingdom

Fig I. Shaded area is the base.

Fig II. A: flaw; B and C: notches cut to hold stone in a setting; D: flaw created by fracture at E; F: fracture created by a blow; G: unpolished cleavage plane; H: basal cleavage plane.

Fig III. Opposite side, showing facets and peak of the "Mountain of Light"

In due course, the Governor-General received the Koh-i-Noor from Dr Login, who had been appointed Governor of the Citadel, on 6 April 1848 under a receipt dated 7 December 1849, in the presence of members of the Board of Administration for the affairs of the Punjab: Sir Henry Lawrence (President), C. G. Mansel, John Lawrence and Sir Henry Elliot (Secretary to the Government of India).

Legend in the Lawrence family has it that before the voyage, John Lawrence left the jewel in his waistcoat pocket when it was sent to be laundered, and was most grateful when it was returned promptly by the valet who found it.[34]

On 1 February 1850, the jewel was sealed in a small iron safe inside a red dispatch box, both sealed with red tape and a wax seal and kept in a chest at Bombay Treasury awaiting a steamer ship from China. It was then sent to England for presentation to Queen Victoria in the care of Captain J. Ramsay and Brevet Lt. Col F. Mackeson under tight security arrangements, one of which was the placement of the dispatch box in a larger iron safe. They departed from Bombay on 6 April on board HMS Medea, captained by Captain Lockyer.

The ship had a difficult voyage: an outbreak of cholera on board when the ship was in Mauritius had the locals demanding its departure, and they asked their governor to open fire on the vessel and destroy it if there was no response. Shortly afterwards, the vessel was hit by a severe gale that blew for some 12 hours.

On arrival in Britain on 29 June, the passengers and mail were unloaded in Plymouth, but the Koh-i-Noor stayed on board until the ship reached Spithead, near Portsmouth, on 1 July. The next morning, Ramsay and Mackeson, in the company of Mr Onslow, the private secretary to the Chairman of the Court of Directors of the British East India Company, proceeded by train to East India House in the City of London and passed the diamond into the care of the chairman and deputy chairman of the East India Company.

The Koh-i-Noor was formally presented to Queen Victoria on 3 July 1850 at Buckingham Palace by the deputy chairman of the East India Company.[32] The date had been chosen to coincide with the Company's 250th anniversary.[35]

The Great Exhibition

Members of the public were given a chance to see the Koh-i-Noor when The Great Exhibition was staged at Hyde Park, London, in 1851. It represented the might of the British Empire and took pride of place in the eastern part of the central gallery.[36]

Its mysterious past and advertised value of £1–2 million drew large crowds.[37] At first, the stone was put inside a gilded birdcage, but after complaints about its dull appearance, the Koh-i-Noor was moved to a case with black velvet and gas lamps in the hope that it would sparkle better.[38] Despite this, the flawed and asymmetrical diamond still failed to please viewers.[3]

1852 re-cutting

Originally, the diamond had 169 facets and was 4.1 centimetres (1.6 in) long, 3.26 centimetres (1.28 in) wide, and 1.62 centimetres (0.64 in) deep. It was high-domed, with a flat base and both triangular and rectangular facets, similar in overall appearance to other Mughal era diamonds which are now in the Iranian Crown Jewels.[39]

Disappointment in the appearance of the stone was not uncommon. After consulting various mineralogists, including Sir David Brewster, it was decided by Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, with the consent of the government, to polish the Koh-i-Noor. One of the largest and most famous Dutch diamond merchants, Mozes Coster, was employed for the task. He sent to London one of his most experienced artisans, Levie Benjamin Voorzanger, and his assistants.[22]

On 17 July 1852, the cutting began at the factory of Garrard & Co. in Haymarket, using a steam-powered mill built specially for the job by Maudslay, Sons and Field.[40] Under the supervision of Prince Albert and the Duke of Wellington, and the technical direction of the queen's mineralogist, James Tennant, the cutting took thirty-eight days. Albert spent a total of £8,000 on the operation,[41] which reduced the weight of the diamond from 186 old carats (191 modern carats or 38.2 g) to its current 105.6 carats (21.12 g).[42] The stone measures 3.6 cm (1.4 in) long, 3.2 cm (1.3 in) wide, and 1.3 cm (0.5 in) deep.[43] Brilliant-cut diamonds usually have fifty-eight facets, but the Koh-i-Noor has eight additional "star" facets around the culet, making a total of sixty-six facets.[5]

The great loss of weight is to some extent accounted for by the fact that Voorzanger discovered several flaws, one especially big, that he found it necessary to cut away.[22] Although Prince Albert was dissatisfied with such a huge reduction, most experts agreed that Voorzanger had made the right decision and carried out his job with impeccable skill.[41] When Queen Victoria showed the re-cut diamond to the young Maharaja Duleep Singh, the Koh-i-Noor's last non-British owner, he was apparently unable to speak for several minutes afterwards.[42]

The much lighter but more dazzling stone was mounted in a honeysuckle brooch and a circlet worn by the queen.[3] At this time, it belonged to her personally, and was not yet part of the Crown Jewels.[22] Although Victoria wore it often, she became uneasy about the way in which the diamond had been acquired. In a letter to her eldest daughter, Victoria, Princess Royal, she wrote in the 1870s: "No one feels more strongly than I do about India or how much I opposed our taking those countries and I think no more will be taken, for it is very wrong and no advantage to us. You know also how I dislike wearing the Koh-i-Noor".[44]

Crown Jewel

After Queen Victoria's death, the Koh-i-Noor was set in the Crown of Queen Alexandra, the wife of Edward VII, that was used to crown her at their coronation in 1902. The diamond was transferred to Queen Mary's Crown in 1911,[45] and finally to The Queen Mother's Crown in 1937.[46] When The Queen Mother died in 2002, the crown was placed on top of her coffin for the lying-in-state and funeral.[47]

All these crowns are on display in the Jewel House at the Tower of London with crystal replicas of the diamond set in the older crowns.[48] The original bracelet given to Queen Victoria can also be seen there. A glass model of the Koh-i-Noor shows visitors how it looked when it was brought to the United Kingdom. Replicas of the diamond in this and its re-cut forms can also be seen in the 'Vault' exhibit at the Natural History Museum in London.[49]

During the Second World War, the Crown Jewels were moved from their home at the Tower of London to Windsor Castle.[50] In 1990, The Sunday Telegraph, citing a biography of the French army general, Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, by his widow, Simonne, reported that George VI hid the Koh-i-Noor at the bottom of a pond or lake near Windsor Castle, about 32 km (20 miles) outside London, where it remained until after the war. The only people who knew of the hiding place were the king and his librarian, Sir Owen Morshead, who apparently revealed the secret to the general and his wife on their visit to England in 1949.[51]

Ownership dispute

The Koh-i-Noor has long been a subject of diplomatic controversy, with India, Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan all demanding its return from the UK at various points.[52]

India

The Government of India, believing the gem was rightfully theirs, first demanded the return of the Koh-i-Noor as soon as independence was granted in 1947. A second request followed in 1953, the year of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Each time, the British government rejected the claims, saying that ownership was non-negotiable.[41]

In 2000, several members of the Indian Parliament signed a letter calling for the diamond to be given back to India, claiming it was taken illegally.[29] British officials said that a variety of claims meant it was impossible to establish the diamond's original owner,[53] and that it had been part of Britain's heritage for more than 150 years.[54]

In July 2010, while visiting India, David Cameron, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, said of returning the diamond, "If you say yes to one you suddenly find the British Museum would be empty. I am afraid to say, it is going to have to stay put".[41] On a subsequent visit in February 2013, he said, "They're not having that back".[55]

In April 2016, the Indian Culture Ministry stated it would make "all possible efforts" to arrange the return of the Koh-i-Noor to India.[56] It was despite the Indian Government earlier conceding that the diamond was a gift. The Solicitor General of India had made the announcement before the Supreme Court of India due to public interest litigation by a campaign group.[57] He said "It was given voluntarily by Ranjit Singh to the British as compensation for help in the Sikh wars. The Koh-i-Noor is not a stolen object".[58]

Pakistan

In 1976, Pakistan asserted its ownership of the diamond, saying its return would be "a convincing demonstration of the spirit that moved Britain voluntarily to shed its imperial encumbrances and lead the process of decolonisation". In a letter to the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, James Callaghan, wrote, "I need not remind you of the various hands through which the stone has passed over the past two centuries, nor that explicit provision for its transfer to the British crown was made in the peace treaty with the Maharajah of Lahore in 1849. I could not advise Her Majesty that it should be surrendered".[59]

Afghanistan

In 2000, the Taliban's foreign affairs spokesman, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, said the Koh-i-Noor was the legitimate property of Afghanistan, and demanded for it to be handed over to the regime. "The history of the diamond shows it was taken from us (Afghanistan) to India, and from there to Britain. We have a much better claim than the Indians", he said.[53] The Afghan claim derives from Shah Shuja Durrani memoirs, which states he surrendered the diamond to Ranjit Singh while Singh was having his son tortured in front of him, so argue the Maharajah of Lahore acquired the stone illegitimately.[60]

In popular culture

The Koh-i-Noor made its first appearance in popular culture in The Moonstone (1868), a 19th-century British epistolary novel by Wilkie Collins, generally considered to be the first full length detective novel in the English language. In his preface to the first edition of the book, Collins says that he based his eponymous "Moonstone" on the histories of two stones: the Orlov, a 189.62-carat (37.9 g) diamond in the Russian Imperial Sceptre, and the Koh-i-Noor.[61] In the 1966 Penguin Books edition of The Moonstone, J. I. M. Stewart states that Collins used G. C. King's The Natural History, Ancient and Modern, of Precious Stones … (1865) to research the history of the Koh-i-Noor.[62] The Koh-i-Noor also features in Agatha Christie's 1925 novel The Secret of Chimneys where it is hidden somewhere inside a large country house and is discovered at the end of the novel. The diamond had been stolen from the Tower of London by a Parisian gang leader who replaced it with a replica stone.[63]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 Israel, p. 176.

- ↑ Balfour, p. 184.

- 1 2 3 Rose, p. 31.

- 1 2 Sucher and Carriere, p. 126.

- 1 2 Smith, p. 77.

- ↑ "Crown Jewels". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 211. United Kingdom: House of Commons. 16 July 1992. col. 944W.

- ↑ "Royal Residences". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 407. United Kingdom: House of Commons. 19 June 2003. col. 353W.

- ↑ Collins English Dictionary. "Definition of 'Koh-i-noor'". HarperCollins. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ↑ https://www.ijsr.net/archive/v3i8/MDYwODE0MDI=.pdf

- ↑ Howie, p. 293.

- ↑ Mears, et al., p. 27.

- ↑ Fanthorpe, p. 202.

- ↑ Mears (1988), p. 100.

- ↑ Kurien, p. 112.

- 1 2 Rose, p. 32.

- ↑ Streeter, pp. 116–117, 130.

- ↑ Lafont, p. 48.

- ↑ Leela Kohli (30 May 1953). "Fascinating history of world's best diamonds". The Northern Star. Lismore, New South Wales: National Library of Australia. p. 6. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ Younghusband and Davenport, pp. 53–57.

- ↑ "Koh-i-Noor: Six myths about a priceless diamond". BBC News. 9 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ↑ Eden, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Davenport, pp. 57–59.

- 1 2 Kim Siebenhüner in Hofmeester and Grewe, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Argenzio, p. 42.

- ↑ Anita Anand (16 February 2016). "The Koh-i-Noor diamond is in Britain illegally. But it should still stay there". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ↑ The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies. 27. W. H. Allen & Co. 1838. p. 177.

- ↑ William Dalrymple (2012). Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan. Bloomsbury. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-408-8183-05.

- ↑ Rastogi, p. 145.

- 1 2 "Indian MPs demand Koh-i-Noor's return". BBC News. 26 April 2000. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- ↑ Login, p. 126.

- ↑ Broun-Ramsay, pp. 87–88

- 1 2 Keay, pp. 156–158

- ↑ Valentine Ball in Jean Baptiste Tavernier, Travels in India, 1889, Macmillan, vol. II, Appendix, plate VI.

- ↑ William Riddell Birdwood (1946). In My Time: Recollections and Anecdotes. Skeffington & Son. p. 85.

- ↑ Tarshis, p. 138.

- ↑ Davis, p. 138.

- ↑ Young, p. 345.

- ↑ Jane Carlyle (11 May 1851). "The Carlyle Letters: The Collected Letters, Volume 26". Duke University Press. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ↑ Sucher and Carriere, pp. 140-141

- ↑ The Illustrated London News. Illustrated London News & Sketch Ltd. 24 July 1852. p. 54.

- 1 2 3 4 Neil Tweedie (29 July 2010). "The Koh-i-Noor: diamond robbery?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- 1 2 Sucher and Carriere, pp. 124, 126.

- ↑ Bari and Sautter, p. 178.

- ↑ Tarling, p. 27.

- ↑ "Queen Mary's Crown". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 31704.

- ↑ "Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother's Crown". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 31703.

- ↑ "Priceless gem in Queen Mother's crown". BBC News. 4 April 2002. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ "The Crown Jewels: Famous Diamonds". Historic Royal Palaces. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ↑ "Glittering finale for the Museum of Life documentary". Natural History Museum. 22 April 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ↑ Hennessy, p. 237.

- ↑ Associated Press (10 June 1990). "British Crown Jewels hidden in lake in World World II, newspaper says". AP News Archive. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ Dalrymple and Anand, p. 13.

- 1 2 Luke Harding (5 November 2000). "Taliban asks the Queen to return Koh-i-Noor gem". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ Andrzej Jakubowski (2015). State Succession in Cultural Property. Oxford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-19-873806-0.

- ↑ Nelson, Sara C. (21 February 2013). "Koh-i-Noor diamond will not be returned to India, David Cameron insists". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ Nida Najar (20 April 2016). "India says it wants one of the Crown Jewels back from Britain". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ "Koh-i-Noor not stolen but gifted: Centre". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. 18 April 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ↑ "India: Koh-i-Noor gem given to UK, not stolen". Sky News. 19 April 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Pakistan Horizon. 29. Pakistan Institute of International Affairs. 1976. p. 267.

- ↑ Jamal, Momin (26 February 2017). "Kohinoor's story: from treachery to treasury". Daily Times. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ↑ Wilkie Collins (1874). The Moonstone: A Novel. Harper & Brothers. p. 8.

- ↑ Goodland, p. 136.

- ↑ Bargainnier, Earl F. (1980). The Gentle Art of Murder: The Detective Fiction of Agatha Christie. Popular Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-87972-159-6. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

Bibliography

- Argenzio, Victor (1977). Crystal Clear: The Story of Diamonds. David McKay Co. ISBN 978-0-679-20317-9.

- Balfour, Ian (2009). Famous Diamonds. Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 978-1-85149-479-8.

- Bari, Hubert; Sautter, Violaine (2001). Diamonds: In the Heart of the Earth, in the Heart of Stars, at the Heart of Power. Vilo International. ISBN 978-2-84576-032-5.

- Broun-Ramsay, James Andrew (1911). Private Letters (2 ed.). India: Blackwood.

- Dalrymple, William; Anand, Anita (2017). Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous Diamond. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-408-88886-5.

- Davenport, Cyril (1897). The English Regalia. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co.

- Davis, John R. (1999). The Great Exhibition. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-1614-1.

- Dixon-Smith, Sally; Edwards, Sebastian; Kilby, Sarah; Murphy, Clare; Souden, David; Spooner, Jane; Worsley, Lucy (2010). The Crown Jewels: Souvenir Guidebook. Historic Royal Palaces. ISBN 978-1-873993-13-2.

- Eden, Emily (1844). Portraits of the Princes and People of India. J. Dickinson & Son. p. 14.

- Fanthorpe, Lionel; Fanthorpe, Patricia (2009). Secrets of the World's Undiscovered Treasures. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-77070-508-1.

- Goodlad, Lauren M. E. (2015). The Victorian Geopolitical Aesthetic: Realism, Sovereignty, and Transnational Experience. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-872827-6.

- Hennessy, Elizabeth (1992). A Domestic History of the Bank of England, 1930–1960. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39140-5.

- Hofmeester, Karin; Grewe, Bernd-Stefan, eds. (2016). Luxury in Global Perspective: Objects and Practices, 1600–2000. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-10832-5.

- Howie, R. A. (1999). "Book Reviews" (PDF). Mineralogical Magazine. Vol. 63 no. 2. Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Israel, Nigel B. (1992). "'The Most Unkindest Cut of All' - Recutting the Koh-i-Nur". Journal of Gemmology. 23 (3): 176. ISSN 0022-1252.

- Keay, Anna (2011). The Crown Jewels. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51575-4.

- Kurien, T. K. (1980). Geology and Mineral Resources of Andhra Pradesh. Geological Survey of India.

- Lafont, Jean Marie (2002). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Lord of the Five Rivers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-566111-8.

- Login, Lena Campbell (1890). Sir John Login and Duleep Singh. Punjab: Languages Dept.

- Mears, Kenneth J. (1988). The Tower of London: 900 Years of English History. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-2527-4.

- Mears, Kenneth J.; Thurley, Simon; Murphy, Claire (1994). The Crown Jewels. Historic Royal Palaces. ASIN B000HHY1ZQ.

- Rastogi, P. N. (1986). Ethnic Tensions in Indian Society: Explanation, Prediction, Monitoring and Control. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-9-997-38489-8.

- Rose, Tessa (1992). The Coronation Ceremony and the Crown Jewels. HM Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-117-01361-2.

- Smith, Henry George (1896). Gems and Precious Stones. Charles Potter.

- Streeter, Edwin William; Hatten, Joseph (1882). The Great Diamonds of the World. G. Bell & Sons.

- Sucher, Scott D.; Carriere, Dale P. (2008). "The Use of Laser and X-ray Scanning to Create a Model of the Historic Koh-i-Noor Diamond". Gems & Gemology. 44 (2): 124–141. doi:10.5741/GEMS.44.2.124.

- Tarling, Nicholas (April 1981). "The Wars of British Succession" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of History. University of Auckland. 15 (1). ISSN 0028-8322.

- Tarshis, Dena K. (2000). "The Koh-i-Noor Diamond and its Glass Replica at the Crystal Palace Exhibition". Journal of Glass Studies. Corning Museum of Glass. 42. ISSN 0075-4250. JSTOR 24191006.

- Young, Paul (2007). ""Carbon, Mere Carbon": The Kohinoor, the Crystal Palace, and the Mission to Make Sense of British India". Nineteenth‐Century Contexts. 29 (4): 343–358. doi:10.1080/08905490701768089.

- Younghusband, Sir George; Davenport, Cyril (1919). The Crown Jewels of England. Cassell & Co. ASIN B00086FM86.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Koh-i-Noor Diamond. |

- The Koh-i-Noor Diamond at h2g2