Kleptoplasty

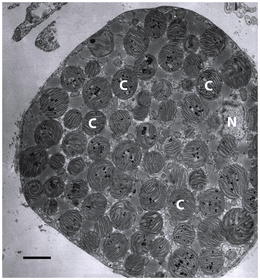

C = chloroplast,

N = cell nucleus.

Electron micrograph: scale bar is 3 µm.

Kleptoplasty or kleptoplastidy is a symbiotic phenomenon whereby plastids, notably chloroplasts from algae, are sequestered by host organisms. The word is derived from Kleptes (κλέπτης) which is Greek for thief. The alga is eaten normally and partially digested, leaving the plastid intact. The plastids are maintained within the host, temporarily continuing photosynthesis and benefiting the predator.[1] The term was coined in 1990 to describe chloroplast symbiosis.[2][3]

Ciliates

Myrionecta rubra is a ciliate that steals chloroplasts from the cryptomonad Geminigera cryophila.[4] M. rubra participates in additional endosymbiosis by transferring its plastids to its predators, the dinoflagellate planktons belonging to the genus Dinophysis.[5]

Karyoklepty is a related process in which the nucleus of the prey cell is kept by the predator as well. This was first described in M. rubra.[6]

Dinoflagellates

The stability of transient plastids varies considerably across plastid-retaining species. In the dinoflagellates Gymnodinium spp. and Pfisteria piscicida, kleptoplastids are photosynthetically active for only a few days, while kleptoplastids in Dinophysis spp. can be stable for 2 months.[1] In other dinoflagellates, kleptoplasty has been hypothesized to represent either a mechanism permitting functional flexibility, or perhaps an early evolutionary stage in the permanent acquisition of chloroplasts.[7]

Sacoglossan sea slugs

_(2).jpg)

The only known animals that practice kleptoplasty are sea slugs in the clade Sacoglossa.[8] Several species of Sacoglossan sea slugs capture intact, functional chloroplasts from algal food sources, retaining them within specialized cells lining the mollusc's digestive diverticula. The longest known kleptoplastic association, which can last up to ten months, is found in Elysia chlorotica,[2] which acquires chloroplasts by eating the alga Vaucheria litorea, storing the chloroplasts in the cells that line its gut.[9] Juvenile sea slugs establish the kleptoplastic endosymbiosis when feeding on algal cells, sucking out the cell contents, and discarding everything except the chloroplasts. The chloroplasts are phagocytosed by digestive cells, filling extensively branched digestive tubules, providing their host with the products of photosynthesis.[10] It is not resolved, however, whether the stolen plastids actively secrete photosynthate or whether the slugs profit indirectly from slowly degrading kleptoplasts.[11]

This very unusual ability has led to these sacoglossans being referred to as "solar-powered sea slugs", but the effect of inhibiting photosynthesis is only marginal, if present at all, on the survival rate some species analyzed[12] and that some species even die in the presence of CO2-fixing kleptoplasts due to elevated levels of reactive oxygen species.[13]

Nudibranchs

Some species of nudibranchs such as Pteraeolidia ianthina sequester whole living symbiotic zooxanthellae within their digestive diverticula, and thus are also "solar-powered".

Foraminifera

Some species of the foraminiferan genera Bulimina, Elphidium, Haynesina, Nonion, Nonionella, Nonionellina, Reophax, and Stainforthia have been shown to sequester diatom chloroplasts.[14]

See also

References

- 1 2 Minnhagen S, Carvalho WF, Salomon PS, Janson S (September 2008). "Chloroplast DNA content in Dinophysis (Dinophyceae) from different cell cycle stages is consistent with kleptoplasty". Environ. Microbiol. 10 (9): 2411–7. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01666.x. PMID 18518896. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- 1 2 S. K. Pierce; S. E. Massey; J. J. Hanten; N. E. Curtis (June 1, 2003). "Horizontal Transfer of Functional Nuclear Genes Between Multicellular Organisms". Biol. Bull. 204 (3): 237–240. doi:10.2307/1543594. JSTOR 1543594. PMID 12807700. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ↑ Clark, K. B., K. R. Jensen, and H. M. Strits (1990). "Survey of functional kleptoplasty among West Atlantic Ascoglossa (=Sacoglossa) (Mollusca: Opistobranchia)". The Veliger. 33: 339–345. ISSN 0042-3211.

- ↑ Johnson, Matthew D.; Oldach, David; Charles, F. Delwiche; Stoecker, Diane K. (Jan 2007). "Retention of transcriptionally active cryptophyte nuclei by the ciliate Myrionecta rubra". Nature. 445 (7126): 426–8. doi:10.1038/nature05496. PMID 17251979.

- ↑ Nishitani, G.; Nagai, S.; Baba, K.; Kiyokawa, S.; Kosaka, Y.; Miyamura, K.; Nishikawa, T.; Sakurada, K.; Shinada, A.; Kamiyama, T. (2010). "High-level congruence of Myrionecta rubra prey and Dinophysis species plastid identities as revealed by genetic analyses of isolates from Japanese coastal waters". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 76 (9): 2791–2798. doi:10.1128/AEM.02566-09. PMC 2863437. PMID 20305031.

- ↑ Johnson, Matthew D.; Oldach, David; et al. (25 January 2007). "Retention of transcriptionally active cryptophyte nuclei by the ciliate Myrionecta rubra". Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 445 (7126): 426–428. doi:10.1038/nature05496. PMID 17251979. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Gast RJ, Moran DM, Dennett MR, Caron DA (January 2007). "Kleptoplasty in an Antarctic dinoflagellate: caught in evolutionary transition?". Environ. Microbiol. 9 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01109.x. PMID 17227410. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ↑ Händeler, K.; Grzymbowski, Y. P.; Krug, P. J.; Wägele, H. (2009). "Functional chloroplasts in metazoan cells - a unique evolutionary strategy in animal life". Frontiers in Zoology. 6: 28. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-6-28. PMC 2790442. PMID 19951407.

- ↑ Catherine Brahic (24 November 2008). "Solar-powered sea slug harnesses stolen plant genes". New Scientist. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ "SymBio: Introduction-Kleptoplasty". University of Maine. Archived from the original on 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ↑ de Vries, Jan; Christa, Gregor; Gould, Sven B. (2014). "Plastid survival in the cytosol of animal cells". Trends in Plant Science. 19 (6): 347–350. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2014.03.010. ISSN 1360-1385.

- ↑ De Vries, Jan; Rauch, Cessa; Christa, Gregor; Gould, Sven B. (2014). "A sea slug's guide to plastid symbiosis". Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae. 83 (4): 415–421. doi:10.5586/asbp.2014.042. ISSN 2083-9480.

- ↑ de Vries, J.; Woehle, C.; Christa, G.; Wagele, H.; Tielens, A. G. M.; Jahns, P.; Gould, S. B. (2015). "Comparison of sister species identifies factors underpinning plastid compatibility in green sea slugs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1802): 20142519–20142519. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2519. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 4344150. PMID 25652835.

- ↑ Bernhard, Joan M.; Bowser, Samuel S. (1999). "Benthic foraminifera of dysoxic sediments: chloroplast sequestration and functional morphology". Earth-Science Reviews. 46: 149–165. doi:10.1016/s0012-8252(99)00017-3.

External links

- "Solar Powered Sea Slugs". ABC Science Online. June 2007. Retrieved 2008-11-24.