Kesterite

| Kesterite | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Sulfide mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Cu2(Zn,Fe)SnS4 |

| Strunz classification | 2.CB.15a |

| Crystal system | Tetragonal |

| Crystal class |

Disphenoidal (4) H-M symbol: (4) |

| Space group | I4 |

| Unit cell | a = 5.427, c = 10.871 [Å]; Z = 2 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Greenish black |

| Crystal habit | Massive, pseudocubic |

| Cleavage | None |

| Mohs scale hardness | 4.5 |

| Luster | Metallic |

| Streak | Black |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| Specific gravity | 4.54–4.59 (meas.); 4.524 (calc.) |

| References | [1][2][3] |

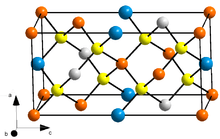

Kesterite is a sulfide mineral with a formula Cu2(Zn,Fe)SnS4. In its lattice structure, zinc and iron atoms share the same lattice sites. Kesterite is the Zn-rich variety whereas the Zn-poor form is called ferrokesterite or stannite. Owing to their similarity, kesterite is sometimes called isostannite.[4] The synthetic form of kesterite is abbreviated as CZTS (from copper zinc tin sulfide). The name kesterite is sometimes extended to include this synthetic material and also CZTSe, which contains selenium instead of sulfur.[5][6]

Occurrence

Kesterite was first described in 1958 in regard to an occurrence in the Kester deposit (and the associated locality) in Yana basin, Yakutia, Russia, where it was discovered.[1][2][3]

It is usually found in quartz-sulfide hydrothermal veins associated with tin ore deposits.[1] Associated minerals include arsenopyrite, stannoidite, chalcopyrite, chalcocite, sphalerite and tennantite.[3]

Stannite and kesterite occur together in the Ivigtut cryolite deposit of South Greenland. Solid solutions form between Cu2FeSnS4 and Cu2ZnSnS4 at temperatures above 680 °C. This accounts for the exsolved kesterite in stannite found in the cryolite.[7]

Use

Kesterite like substances are being researched as a solar photovoltaic material.[8]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kësterite. |

- 1 2 3 Kesterite. Webmineral

- 1 2 Kesterite. Mindat.org

- 1 2 3 Kesterite. Handbook of Mineralogy

- ↑ Bernhard Pracejus (2008). The ore minerals under the microscope: an optical guide. Elsevier. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-0-444-52863-6.

- ↑ Uwe Rau; Daniel Abou-Ras; Thomas Kirchartz (2011). Advanced Characterization Techniques for Thin Film Solar Cells. John Wiley & Sons. p. 351. ISBN 978-3-527-63629-7.

- ↑ Ingrid Repins, Nirav Vora, Carolyn Beall, Su-Huai Wei, Yanfa Yan, Manuel Romero, Glenn Teeter, Hui Du, Bobby To, Matt Young, and Rommel Noufi. "Kesterites and Chalcopyrites: A Comparison of Close Cousins" Presented at the 2011 Materials Research Society Spring Meeting San Francisco, California, April 25–29, 2011 NREL Preprint

- ↑ S Karup-Møller, Galena and Associated Ore Minerals from the Cryolite at Ivigtut, South Greenland, Commission for Scientific Research in Greenland, 1979, pp. 8-9 ISBN 978-87-17-02582-0

- ↑ C&EN, Mark Peplow, special to (12 February 2018). "Kesterite solar cells get ready to shine | February 12, 2018 Issue - Vol. 96 Issue 7 | Chemical & Engineering News". cen.acs.org. 96 (7): 15–18.