Kellogg–Briand Pact

| General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Signed | 27 August 1928 |

| Location | Quai d'Orsay, Paris, France |

| Effective | 24 July 1929 |

| Negotiators | |

| Original signatories | |

| Signatories |

31 signatories by effective date

9 countries once in force |

|

| |

The Kellogg–Briand Pact (or Pact of Paris, officially General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy[1]) is a 1928 international agreement in which signatory states promised not to use war to resolve "disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them".[2] Parties failing to abide by this promise "should be denied of the benefits furnished by [the] treaty". It was signed by Germany, France, and the United States on 27 August 1928, and by most other states soon after. Sponsored by France and the U.S., the Pact renounces the use of war and calls for the peaceful settlement of disputes. Eleven years after the Paris signing, World War II had begun. Similar provisions were incorporated into the Charter of the United Nations and other treaties and it became a stepping-stone to a more activist American policy.[3] It is named after its authors, United States Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand. The pact was concluded outside the League of Nations, and remains in effect.[4]

As a practical matter, the Kellogg–Briand Pact did not live up to all of its aims, but has arguably had some success. It did not end war, nor stop the rise of militarism, and was unable to keep the international peace in succeeding years.[5] The Pact has been ridiculed for its moralism and legalism and lack of influence on foreign policy. Moreover, it erased the legal distinction between war and peace because the signatories began to wage wars without declaring them.[6]

The pact's central provisions renouncing the use of war, and promoting peaceful settlement of disputes and the use of collective force to prevent aggression, were incorporated into the United Nations Charter and other treaties. Although civil wars continued, wars between established states have been rare since 1945, with a few exceptions in the Middle East.[3] One legal consequence is that it is unlawful to annex territory by force, although other forms of annexation have not been prevented. More broadly, some authors claim there is now a strong presumption against the legality of using, or threatening, military force against another country.[7] The pact also served as the legal basis for the concept of a crime against peace, for which the Nuremberg Tribunal and Tokyo Tribunal tried and executed the top leaders responsible for starting World War II.[8]

Many historians and political scientists see the pact as mostly irrelevant and ineffective.[9]

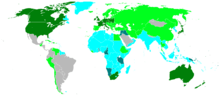

Signatories and adherents

After negotiations, the pact was signed in Paris at the French Foreign Ministry by the representatives from Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czechoslovakia, France, Germany, British India, the Irish Free State, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Poland, South Africa, the United Kingdom[10] and the United States. It was provided that it would come into effect on 24 July 1929.

By that date, the following nations had deposited instruments of definitive adherence to the pact: Afghanistan, Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, China, Cuba, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Egypt, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, Guatemala, Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Liberia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, Peru, Portugal, Romania, the Soviet Union, the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, Siam, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and Turkey. Eight further states joined after that date (Persia, Greece, Honduras, Chile, Luxembourg, Danzig, Costa Rica and Venezuela[11]) for a total of 62 signatories. In 1971, Barbados declared its accession to the treaty.[12]

In the United States, the Senate approved the treaty overwhelmingly, 85–1, with only Wisconsin Republican John J. Blaine voting against over concerns with British imperialism.[13][14] While the U.S. Senate did not add any reservation to the treaty, it did pass a measure which interpreted the treaty as not infringing upon the United States' right of self-defense and not obliging the nation to enforce it by taking action against those who violated it.[15]

Briand speaking

Briand speaking Stresemann signing

Stresemann signing Mackenzie King signing

Mackenzie King signing

Effect and legacy

The 1928 Kellogg–Briand Pact was concluded outside the League of Nations, and remains in effect.[4] One month following its conclusion, a similar agreement, General Act for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes, was concluded in Geneva, which obliged its signatory parties to establish conciliation commissions in any case of dispute.[16] The pact's central provisions renouncing the use of war, and promoting peaceful settlement of disputes and the use of collective force to prevent aggression, were incorporated into the United Nations Charter and other treaties. Although civil wars continued, wars between established states have been rare since 1945, with a few exceptions in the Middle East.[3]

As a practical matter, the Kellogg–Briand Pact did not live up to all of its aims, but has arguably had some considerable success. It did not end war or stop the rise of militarism, and was unable to keep the international peace in succeeding years.[17] Moreover, it erased the legal distinction between war and peace because the signatories, having renounced the use of war, began to wage wars without declaring them as in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935, the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939, and the German and Soviet invasions of Poland.[6] However, the pact is associated with a marked decline in territorial conquest of one nation by another in the periods before and after its signing: the period from 1816 to 1928 saw on average one conquest every 10 months and 114,088 square miles of territory taken per year, while the period since World War Two has seen one conquest every four years and 5,772 square miles of territory taken per year. After WWII, territories that had been conquered between 1928 and WWII, with some exceptions, were mostly returned to the countries that had originally held them.[18]

While the Pact has been ridiculed for its moralism and legalism and lack of influence on foreign policy, it instead led to a more activist American foreign policy.[3] According to Yale law professors Scott J. Shapiro and Oona A. Hathaway, one reason for the historical insignificance of the pact was the absence of an enforcement mechanism to compel compliance from signatories. They also said that the Pact appealed to the West because it promised to secure and protect previous conquests, thus securing their place at the head of the international legal order indefinitely.[19]

The pact, in addition to binding the particular nations that signed it, has also served as one of the legal bases establishing the international norms that the threat[20] or use of military force in contravention of international law, as well as the territorial acquisitions resulting from it,[21] are unlawful.

Notably, the pact served as the legal basis for the concept of a crime against peace. It was for committing this crime that the Nuremberg Tribunal and Tokyo Tribunal tried and executed the top leaders responsible for starting World War II.[8] The interdiction of aggressive war was confirmed and broadened by the United Nations Charter, which provides in article 2, paragraph 4, that "All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations." One legal consequence is that it is unlawful to annex territory by force, although other forms of annexation have not been prevented. More broadly, there is now a strong presumption against the legality of using, or threatening, military force against another country. Nations that have resorted to the use of force since the Charter came into effect have typically invoked self-defense or the right of collective defense.[7]

Political scientists Oona A. Hathaway and Scott J. Shapiro in 2017 claim:

- As its effects reverberated across the globe, it reshaped the world map, catalyzed the human rights revolution, enabled the use of economic sanctions as a tool of law enforcement, and ignited the explosion in the number of international organizations that regulate so many aspects of our daily lives.[22]

Footnotes

- ↑ See certified true copy of the text of the treaty in League of Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 94, p. 57 (No. 2137)

- ↑ Kellogg–Briand Pact 1928, Yale University

- 1 2 3 4 Josephson, Harold (1979). "Outlawing War: Internationalism and the Pact of Paris". Diplomatic History. 3 (4): 377–390. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1979.tb00323.x.

- 1 2 Westminster, Department of the Official Report (Hansard), House of Commons,. "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 16 Dec 2013 (pt 0004)". publications.parliament.uk.

- ↑ "The Kellogg-Briand Pact, 1928". Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations. Office of the Historian, United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- 1 2 Quigley, Carroll (1966). Tragedy And Hope. New York: Macmillan. pp. 294–295.

- 1 2 Silke Marie Christiansen (2016). Climate Conflicts - A Case of International Environmental and Humanitarian Law. Springer. p. 153. ISBN 9783319279459.

- 1 2 Kelly Dawn Askin (1997). War Crimes Against Women: Prosecution in International War Crimes Tribunals. p. 46. ISBN 978-9041104861.

- ↑ "There's Still No Reason to Think the Kellogg-Briand Pact Accomplished Anything". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ Kellogg–Briand, What do they know

- ↑ Kellogg-Briand Pact 1928, Yale University

- ↑ "UNTC". treaties.un.org.

- ↑ "John James Blaine". Dictionary of Wisconsin History. Accessed 11 November 2008.

- ↑ "Senate Ratifies Anti-War Pact". The Milwaukee Journal. United Press. 1929-01-16. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- ↑ "The Avalon Project : The Kellogg-Briand Pact - Hearings Before the Committee on Foreign Relations United States". avalon.law.yale.edu.

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 93, pp. 344–363.

- ↑ "Milestones: 1921–1936 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov.

- ↑ Hathaway, Oona A.; Shapiro, Scott J. (2 September 2017). "Outlawing War? It Actually Worked". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ↑ Menand, Louis (18 September 2017). "Drop Your Weapons". The New Yorker. Condé Nast.

Hathaway and Shaprio acknowledge that one reason the Kellogg–Briand Pact is regarded as historically insignificant is that it provided no enforcement mechanism.

- ↑ Article 2, Budapest Articles of Interpretation Archived 25 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. (see under footnotes), 1934

- ↑ Article 5, Budapest Articles of Interpretation Archived 25 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. (see under footnotes), 1934

- ↑ Hathaway, Oona A.; Shapiro, Scott J. (2017). The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World. Simon and Schuster. p. xv. ISBN 978-1-5011-0986-7.

Further reading

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Ellis, Lewis Ethan. Frank B. Kellogg and American foreign relations, 1925–1929 (1961).

- Ellis, Lewis Ethan. Republican foreign policy, 1921–1933 (1968).

- Ferrell, Robert H. (1952). Peace in Their Time: The Origins of the Kellogg-Briand Pact. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0393004915.

- Hathaway, Oona A. and Scott J. Shapiro. The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World (2017), 581 pp. online review