Kamarupa of Bhaskaravarman

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Kamarupa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ruling dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Varman dynasty (350–650 CE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mlechchha dynasty (650–900 CE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pala Dynasty (900–1100 CE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kamarupa of Bhaskaravarman is a period of Kamarupa kingdom during the reign of king Bhaskaravarman (600–650) of the Varman dynasty. Bhaskaravarman was perhaps the most illustrious of the monarchs of ancient Kamarupa. His name has been immortalised by the accounts which Xuanzang and his biographers have left. During his time, Kamarupa was one of the most advanced kingdoms in India.[1]

Country

Xuanzang notes that the country of Kamarupa was low and moist and that the crops were regular. Cocoa-nuts and jack-fruits grew abundantly and were appreciated by the people. The climate was genial.[2]

The description is of Kamarupa proper and not of the extensive dominions of Bhaskaravarman towards the west. Evidently the pilgrim came into the present district of Kamarupa and the capital of that time was probably the old Pragjyotishpura or Guwahati. The pilgrim, with the king and his retinue, must have therefore proceeded down the Brahmaputra and reached the Ganges by a stream which connected the two rivers and then going tip the Ganges reached Rajmahal. The countries passed throngh were both Kamarupa and Karnasuvarna (Central Bengal).[3]

Bhaskaravarman would not have selected this route if Karnasuvarna was not then under his sway. According to the account given in the Si-yu-ki the circumference of Kamarupa was about 1700 miles. As Gait has pointed out, this circumference must have included the whole of the Assam Valley, the whole of the Surma Valley, a part of North Bengal and a part of Mymensing. The question whether Sylhet was included within the kingdom at that time is a matter of some doubt. The Nidhanpur copper-plate was found in Panchakhanda within the district of Sylhet. Gait argues from this that Sylhet was within the dominions of Bhaskaravarman.[4]

Extent

Sir Edward Gait, relying on Vincent Smith and Pandit Padmanath Vidya Vinod, holds that Bhaskaravarman came into possession of Karnasuvarna after the death of Sri Harsha. This supposition is evidently incorrect.[5]

Sasanka held sway over central and lower Bengal and also perhaps over part of Magadha and Orissa. It appears that being overthrown by Bhaskaravarman in Karnasuvarna he retired to the south and continued to rule there as evidenced by the Ganjam inscription of Madhavavarman, a Samanta under him.[6] This inscription is dated 619 A.D. and from this fact Pandit Vidyavinod and some other scholars have wrongly assumed that Sasanka continued to rule at Karnasuvarna till 619 A.D. Nagendranath Basu believes that after the alliance between Sri Harsha and Bhaskaravarman, Sasanka lost Karnasuvarna and was obliged to retire to the hilly country in the south.[7] He holds also that probably Sri Harsha allowed Bhaskaravarman to rule over Gauda and Karnasuvarna and established Madhava Gupta, son of Mahasena Gupta, in Magadha as a vassal ruler. This was probably the fact. R.D Banerji also thinks that Sasanka was overthrown by the combined efforts of Bhaskaravarman and Sri Harsha.[8] In his work, the History of Orissa, R. D. Banerji writes:[9]

| “ | Whatever be the real origin of Sasanka, there is no doubt about the fact that eventually be was driven out of Karnasuvarna. It is quite possible that this event had taken place before the date of the Ganjam plate and at that time he had lost his possessions in Bengal and was the master of Orissa only. | ” |

The theory of Sir Edward Gait and Vincent Smith that Bhaskaravarman acquired Karnasuvarna after the death of Sri Harsha is therefore quite incorrect. It is reasonable to suppose that Sasanka was driven out of Karnasuvarna about 610 A.D.[9]

The coronation of Sri Harsha took place about 612 A.D. after Sasanka had been overthrown and Bhaskaravarman had come into possession of Karnasuvarna. A writer in the Indian Historical Quarterly[10] points out that Sri Harsha's sway never reached Bengal and that Sasanka's kingdom passed to Bhaskaravarman as otherwise he could not have controlled the sea-route to China and promised a safe passage to Xuanzang.[11] It appears clear from Bana's Harsha Charita that after the alliance with Bhaskaravarman, Sri Harsha felt at ease concerning the conquest of Gauda and despatching his cousin Bhandi to invade Gauda (perhaps in collaboration with Bhaskaravarman), he himself set out to search for his sister Rajyasri who had escaped to the jungles of Vindhya. Karnasuvarna was actually conquered by Bhaskaravarman as stated in the Nidhanpur plate. Another well known scholar, Mr. Ramaprasad Chanda, writing in a Bengali magazine, rejects Vidyavavinod's theory that Bhaskaravarman occupied Karnasuvarna only temporarily and holds that during; the seventh century Gauda was included within the kingdom of Kamarupa.[12] Beal, in his introduction to the biography, states, "Bhaskaravarman the king of Kamarupa and probably former kings of that kingdom had the sea-route to China under their special protection".[13] Perhaps Beal would have been more correct if he had stated that Bhaskaravarman and his successors had the control over the Tamralipti region and the sea-route for at least 100 years after the death of Bhaskaravarman.[14]

Religion

Bhaskaravarman was a Hindu by religion spreading "the light of Arya Dharma" though he had great reverence for learned Buddhist priests and professors of his time and was distinctly inclined towards Buddhism. The text of his messages to Silabhadra leave no doubt on this point.[15] The general populace worshipped the Devas and did not believe in Buddhism. The Deva-temples were some hundreds in number and the various systems had some myriads of professed adherents. Xuanzang notes that the few Buddhists in the country performed their acts of devotion in secret.[2]

Cultural growth

According to Xuanzang, the people of Kamarupa were honest albeit with a violent disposition but were persevering students. He mentioned that the people were are short height and of yellow complexion. Their speech differed from that of mid-India, i.e. Magadha and Mithila.[16]

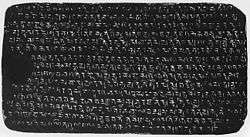

The Nidhanpur grant was issued from Karnasuvarna and the text of the inscription must therefore have been composed by a pandit of that part of the country who was named Vasuvarna. This probably explains the occurrence in this inscription of expressions and passages which we do not find in subsequent Kamarupa inscriptions, but which used to be inscribed in plates issued by the Gupta kings of Magadha and Pundravardhana and the subsequent Pala rulers of Gauda and Magadha. There are also names of offices mentioned in this inscription which do not occur in subsequent Kamarupa inscriptions. The "officer issuing hundred commands who has obtained the pancha mahh sabda" is not mentioned in subsequent inscriptions.[17]

It seems that Bhaskaravarman after his conquest of Karnasuvarna and Gauda, finding himself in the exalted position of an emperor, introduced this high office, probably in imitation of the Gupta emperors. The expression "prapta pancha maha sabda" probably means the holder of five offices each of which is styled Maha or great such as Mahasamanta, Maha-sainya-pati (ride stray-plate of Harjara), Maha-sandhivi grahik and so forth.[17]

The person named in this inscription, who was to mark out the boundaries of the lands comprised in the grant, was Srikshi Kunda, the headman of Chandrapuri. The donees named in the plate, who were all Nagar Brahmans, included seven persons with the surname Kunda. Srikshi Kunda was therefore himself also a Nagar Brahman. The nyaya karanika, was evidently a judge and it appears that this office existed till the medieval regime. The Bhandaragaradhikara meant the officer in charge of the royal treasury. This office also, though not mentioned in subsequent inscriptions, existed till the time of the medieval kings. The revenue collector is called Utkhetayita and the engraver of the inscription on the copperplate is called Sekyakara. One Kaliya was the engraver of this inscription and it is a common Kamrupi name even till now.[18]

Art and industry

Arts and industries had then advanced to a remarkable extent. From the Harsha Charita of Bana it can find a list of the presents which Bhaskaravarman sent to Sri Harsha through his trusted envoy Hangshavega. These presents included an ingenuously constructed royal umbrella of exquisite workmanship studded with valuable gems, puthis written on Sachi bark, dyed cane mats, Agar-essence, musk in silk bags, liquid molasses in earthen pots, utensils, paintings, a pair of Brahmani ducks in a cage made of cane and overlaid with gold and a considerable quantity of silk fabrics some of which were so even and polished that they resembled Bhujapatra (probably Muga and pat fabrics).[19]

This list alone is sufficient to show that the arts and industries of Kamarupa, at such a distant period, reached a very high state of perfection. The Chinese accounts say that Bhaskaravarman could muster a fleet of 30,000 ships and an army of 20,000 elephants clad in mail. This may have been an overestimate but, even making due allowances for exaggeration we can conclude that Bhaskaravarman was a very powerful monarch and that during his time boat-building was a flourishing industry in Kamarupa and that iron, which must have been then available in abundance from the Khasi Hills, was largely manufactured into accoutrements of war.[19]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Barua 1933, pp. 90,91.

- 1 2 Barua 1933, p. 85.

- ↑ Barua 1933, p. 86.

- ↑ Barua 1933, p. 88.

- ↑ Barua 1933, p. 66.

- ↑ Epigraphia Indica Vol VI. p. 144.

- ↑ Bangalar Jatiya Itihaas Vol I. p. 65.

- ↑ Bangalar Jatiya Itihas Vil I. p. 87.

- 1 2 Barua 1933, p. 67.

- ↑ Sarka, Bejoynath. Finger Posts Of Bengal History. Indian Historical Quarterly Vol VI. p. 442.

- ↑ Life of Hiuen Tsiang. p. 188.

- ↑ Baisakh Prabashi 1339. p. 62.

- ↑ Beal, Samuel. Introduction to the life of Hieun Tsiang. p. 16.

- ↑ Barua 1933, p. 68.

- ↑ Barua 1933, p. 91.

- ↑ Barua 1933, p. 93.

- 1 2 Barua 1933, p. 94.

- ↑ Barua 1933, p. 95.

- 1 2 Barua 1933, p. 96.

References

- Barua, Kanak Lal (1933). Early History Of Kamarupa.

Further reading

- Vasu, Nagendranath (1922). The Social History of Kamarupa.

- Tripathi, Chandra Dhar (2008). Kamarupa-Kalinga-Mithila politico-cultural alignment in Eastern India : history, art, traditions. Indian Institute of Advanced Study. p. 197.

- Wilt, Verne David (1995). Kamarupa. V.D. Wilt. p. 47.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 538.

- Kapoor, Subodh (2002). Encyclopaedia of ancient Indian geography. Cosmo Publications. p. 364.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 668.

- Kapoor, Subodh (2002). The Indian encyclopaedia: biographical, historical, religious,administrative, ethnological, commercial and scientific. Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 320.

- Sarkar, Ichhimuddin (1992). Aspects of historical geography of Pragjyotisha-Kamarupa (ancient Assam). Naya Prokash. p. 295.

- Deka, Phani (2007). The great Indian corridor in the east. Mittal Publications. p. 404.

- Pathak, Guptajit (2008). Assam's history and its graphics. Mittal Publications. p. 211.

- Samiti, Kamarupa Anusandhana (1984). Readings in the history & culture of Assam. Kamrupa Anusandhana Samiti. p. 227.