Judgment at Nuremberg

| Judgment at Nuremberg | |

|---|---|

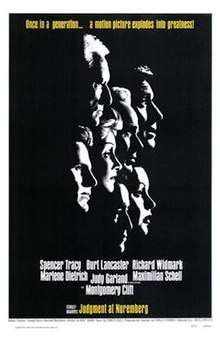

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Stanley Kramer |

| Produced by | Stanley Kramer |

| Screenplay by | Abby Mann |

| Based on |

Judgment at Nuremberg 1959 Playhouse 90 by Abby Mann |

| Starring |

Spencer Tracy Burt Lancaster Richard Widmark Marlene Dietrich Judy Garland Maximilian Schell William Shatner Montgomery Clift Werner Klemperer |

| Music by | Ernest Gold |

| Cinematography | Ernest Laszlo |

| Edited by | Frederic Knudtson |

Production company |

Roxlom Films |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 179 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

English German |

| Budget | $3 million[2] |

| Box office | $10 million[3] |

Judgment at Nuremberg is a 1961 American courtroom drama film directed by Stanley Kramer, written by Abby Mann and starring Spencer Tracy, Burt Lancaster, Richard Widmark, Maximilian Schell, Werner Klemperer, Marlene Dietrich, Judy Garland, William Shatner, and Montgomery Clift.[4] Set in Nuremberg in 1948, the film depicts a fictionalized version of the Judges' Trial of 1947, one of the twelve U.S. military tribunals during the Subsequent Nuremberg trials.

The film centers on a military tribunal led by Chief Trial Judge Dan Haywood (Tracy), before which four German judges and prosecutors (as compared to 16 defendants in the actual Judges' Trial) stand accused of crimes against humanity for their involvement in atrocities committed under the Nazi regime. The film deals with non-combatant war crimes against a civilian population, the Holocaust, and examines the post-World War II geopolitical complexity of the actual Nuremberg Trials. An earlier version of the story was broadcast as a television episode of Playhouse 90.[5] Schell and Klemperer played the same roles in both productions.

In 2013, Judgment at Nuremberg was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[6]

Plot

Judgment at Nuremberg centers on a military tribunal convened in Nuremberg, Germany, in which four German judges and prosecutors stand accused of crimes against humanity for their involvement in atrocities committed under the Nazi regime. Judge Dan Haywood (Spencer Tracy) is the Chief Trial Judge of a three-judge panel that will hear and decide the case against the defendants. Haywood begins his examination by trying to learn how the defendant Ernst Janning (Burt Lancaster) could have sentenced so many people to death. Janning, it is revealed, is a well-educated and internationally respected jurist and legal scholar. Haywood seeks to understand how the German people could have turned blind eyes and deaf ears to the crimes of the Nazi regime. In doing so, he befriends the widow (Marlene Dietrich) of a German general who had been executed by the Allies. He talks with a number of Germans who have different perspectives on the war. Other characters the judge meets are US Army Captain Byers (William Shatner), who is assigned to the American party hearing the cases, and Irene Hoffmann (Judy Garland), who is afraid to provide testimony that may bolster the prosecution's case against the judges.

German defense attorney Hans Rolfe (Maximilian Schell) argues that the defendants were not the only ones to aid, or at least turn blind eyes to, the Nazi regime. He also suggests that the United States has committed acts just as bad or worse as those the Nazis perpetrated. He raises several points in these arguments, such as: US Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.'s support for the first eugenics practices (see Buck v. Bell ); the German-Vatican Reichskonkordat of 1933, which the Nazi-dominated German government exploited as an implicit early foreign recognition of Nazi leadership; Joseph Stalin's part in the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, which removed the last major obstacle to Germany's invasion and occupation of western Poland, initiating World War II; and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the final stage of the war in August 1945.[7]

Janning, meanwhile, decides to take the stand for the prosecution, stating that he is guilty of the crime he is accused of: condemning to death a Jewish man of "blood defilement" charges—namely, that the man slept with a 16-year-old Gentile girl—when he knew there was no evidence to support such a verdict. During his testimony, he explains that well-meaning people like himself went along with Hitler's anti-Semitic racism policies out of a sense of patriotism, even though they knew it was wrong, because of the effects of the post-World War I Versailles Treaty.

Haywood must weigh considerations of geopolitical expediency and ideals of justice. The trial takes place against the background of the Berlin Blockade, and there is pressure to let the German defendants off lightly so as to gain German support in the growing Cold War against the Soviet Union.[8] All four defendants are found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

Haywood visits Janning in his cell. Janning affirms to Haywood that, "By all that is right in this world, your verdict was a just one," but asks him to believe that, regarding the mass murder of innocents, "I never knew that it would come to that." Judge Haywood replies, "Herr Janning, it came to that the first time you sentenced a man to death you knew to be innocent." Haywood departs; a title card informs the audience that, of 99 defendants sentenced to prison terms in Nuremberg trials that took place in the American Zone, none were still serving their sentences as of the film's 1961 release.[9][lower-alpha 1]

Cast

- Spencer Tracy as Chief Judge Dan Haywood

- Burt Lancaster as defendant Dr. Ernst Janning

- Richard Widmark as prosecutor Col. Tad Lawson

- Maximilian Schell as defense counsel Hans Rolfe

- Werner Klemperer as defendant Emil Hahn

- Marlene Dietrich as Frau Bertholt

- Montgomery Clift as Rudolph Peterson

- Judy Garland as Irene Hoffmann-Wallner

- Howard Caine as Hugo Wallner - Irene's husband

- William Shatner as Capt. Harrison Byers

- John Wengraf as His Honour Herr Justizrat Dr. Karl Wieck - former Minister of Justice in Weimar Germany

- Karl Swenson as Dr. Heinrich Geuter - Feldenstein's lawyer

- Ben Wright as Herr Halbestadt, Haywood's butler

- Virginia Christine as Mrs. Halbestadt, Haywood's Housekeeper

- Edward Binns as Senator Burkette

- Torben Meyer as defendant Werner Lampe

- Martin Brandt as defendant Friedrich Hofstetter

- Kenneth MacKenna as Judge Kenneth Norris

- Ray Teal as Judge Curtiss Ives

- Alan Baxter as Brig. Gen. Matt Merrin

- Joseph Bernard as Major Abe Radnitz - Lawson's assistant

- Olga Fabian as Mrs. Elsa Lindnow - witness in Feldenstein case

- Otto Waldis as Pohl

- Paul Busch as Schmidt

- Bernard Kates as Max Perkins

Production

Background

The film's events relate principally to actions committed by the German state against its own racial, social, religious, and eugenic groupings within its borders "in the name of the law" (from the prosecution's opening statement in the film), that began with Hitler's rise to power in 1933. The plot development and thematic treatment question the legitimacy of the social, political and alleged legal foundations of these actions.

The real Judges' Trial focused on 16 judges and prosecutors who served before and during the Nazi regime in Germany and who either passively, actively, or in a combination of both, embraced and enforced laws that led to judicial acts of sexual sterilization and to the imprisonment and execution of people for their religions, racial or ethnic identities, political beliefs and physical handicaps or disabilities.

A key thread in the film's plot involves a "race defilement" trial known as the Feldenstein case. In this fictionalized case, based on the real life Katzenberger Trial, an elderly Jewish man had been tried for having a "relationship" (sexual acts) with an Aryan (German) 16-year-old girl, an act that had been legally defined as a crime under the Nuremberg Laws, which had been enacted by the German Reichstag. Under these laws, the man was found guilty and was put to death in 1935. Using this and other examples, the movie explores individual conscience, collective guilt, and behavior during a time of widespread societal immorality.

The film is notable for its use of courtroom drama to illuminate individual perfidy and moral compromise in times of violent political upheaval; it was one of the first drama films not to shy from showing actual footage filmed by American and British soldiers after the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps. Shown in court by prosecuting attorney Colonel Tad Lawson (Richard Widmark), the scenes of huge piles of naked corpses laid out in rows and bulldozed into large pits were considered exceptionally graphic for a mainstream film of at the time.

The film bridges the gap between English-speaking and German-speaking persons within the courtroom by presenting the film in English, but implying use of the German language through headphones used by characters whose native language is the opposite of that spoken.

Soundtrack

- Lili Marleen

- Music by Norbert Schultze (1938)

- Lyrics by Hans Leip (1915)

- Liebeslied

- Music by Ernest Gold

- Lyrics by Alfred Perry

- Wenn wir marschieren

- German folk song (ca. 1910)

- Care for Me

- By Ernest Gold

- Notre amour ne peur

- By Ernest Gold

- Du, du liegst mir im Herzen

- German folk song, arrangement by Ernest Gold

- Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13

Reception

The world premiere was held on December 14, 1961 at the Kongresshalle in West Berlin.[1] 300 journalists from 22 countries were in attendance,[10] and earphones offering the soundtrack dubbed in German, Spanish, Italian and French were made available.[1] The reaction from the audience was reportedly subdued, with some applauding at the finish but most of the Germans in attendance leaving in silence.[10]

Kramer's film received positive reviews from critics and was liked as a straight reconstruction of the famous trials of Nazi war criminals. The cast was especially praised, including Tracy, Lancaster, Schell, Clift and Garland. The film's release was perfectly timed as its subject coincided with the then trial and conviction in Israel of Nazi official Adolf Eichmann.

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times declared it "a powerful, persuasive film" with "a stirring, sobering message to the world."[11] Variety wrote: "With the most painful pages of modern history as its bitter basis, Abby Mann's intelligent, thought-provoking screenplay is a grim reminder of man's responsibility to denounce grave evils of which he is aware. The lesson is carefully, tastefully and upliftingly told via Kramer's large-scale production."[12] Harrison's Reports awarded its top grade of "Excellent," praising Kramer for employing "an ingenious device of fluid direction" and Spencer Tracy for "a performance of compelling substance."[13] Brendan Gill of The New Yorker called the film "a bold and, despite its great length, continuously exciting picture," which asks questions that "are among the biggest that can be asked and are no less fresh and thrilling for being thousands of years old." Gill added that the cast was so loaded with stars "that it occasionally threatens to turn into a judicial 'Grand Hotel.' Luckily, they all work hard to stay inside their roles."[14] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post declared it "an extraordinary film, both in concept and handling. Those who see this at the Warner will recognize that the screen has been put to noble use."[15] The Monthly Film Bulletin of Britain dissented, writing in a mostly negative review that "this large-scale trial film undermines faith in its philosophical and historical merit by colouring the better part of its message with hackneyed court-room hysteria," explaining that "in a series of contrived scenes ... the point is hammered home right down to the last shock-cut. The same specious technique (zoom-lens shots and camera-circlings predominant) and showmanship turn the trial into little more than a travesty—notably in the melodramatic switch in the character of Janning."[16]

The film grossed $6 million in the United States, and $10 million in world-wide release.[17]

Accolades

The film was nominated for eleven Academy Awards. Maximilian Schell won the award for Best Actor, and Abby Mann won in the Best Adapted Screenplay category. The remaining nominations were for Best Picture, Stanley Kramer for Best Director, Spencer Tracy for Best Actor, Montgomery Clift for Best Supporting Actor, Judy Garland for Best Supporting Actress, Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, Black-and-White, Best Cinematography, Black-and-White, Best Costume Design, Black-and-White, and Best Film Editing.[18] Stanley Kramer was given the prestigious Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award. This is one of the few times that a film had multiple entries in the same category (Tracy and Schell for Best Actor). Many of the big name actors who appeared in the film did so for a fraction of their usual salaries because they believed in the social importance of the project.

In June 2008, the American Film Institute revealed its "Ten Top Ten" after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Judgment at Nuremberg was acknowledged as the tenth best film in the courtroom drama genre.[19] Additionally, the film had been nominated for AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies.[20]

Release

Judgment at Nuremberg was released in American theatres on December 19, 1961. The film was released on DVD special edition on September 7, 2004.[21] On Blu-ray the film was released in two editions – Hollywood Gold Series (April 30, 2014)[22] and Limited Edition to 3000 (November 11, 2014).[23]

Adaptations

In 2001, a stage adaptation of the film was produced for Broadway, starring Schell (this time in the role of Ernst Janning) and George Grizzard, with John Tillinger as director.[24]

See also

- German Concentration Camps Factual Survey, British and American army film of the camps

- List of Holocaust films

- Nuremberg Trials (a Soviet film on the trials)

- Trial films

- War crimes trials

Notes

- ↑ This does not refer to the 1946 Nuremberg trials of the leadership of the Third Reich, which was in front of an international panel of judges, not solely American ones. Of the twenty defendants in that trial, as of 1961 three men still remained in prison: Rudolf Hess, Albert Speer and Baldur von Schirach.

References

- 1 2 3 Scott, John L. (December 14, 1961). "West Berlin Reaction on 'Nuremberg' Awaited". Los Angeles Times: Part IV, p. 7.

- ↑ Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, University of Wisconsin Press, 1987 p. 145

- ↑ Box Office Information for Judgment at Nuremberg. The Numbers. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ↑ "Judgment at Nuremberg full credits". TCM Movie Database.

- ↑ "Playhouse 90 - Season 3, Episode 28: Judgment at Nuremberg - TV.com". TV.com. CBS Interactive.

- ↑ "Library of Congress announces 2013 National Film Registry selections" (Press release). Washington Post. December 18, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ↑ Nixon, Rob. "Pop Culture 101: Judgment at Nuremberg." TCM.com. 2012. Accessed 2012-11-02; Mann, Abby. Judgement at Nuremberg. London: Cassell, 1961, p. 93.

- ↑ Bradley, Sean. "Judgment at Nuremberg". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on 2008-09-13. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

He argues that the love of country led to an attitude of "my country right or wrong." Obedience or disobedience to the Fuehrer would have been a choice between patriotism or treason for the judges. [...] Why did the educated stand aside? Because they loved their country.

- ↑ "Judgement at Nuremberg (1961) FAQ". The Internet Movie Database.

- 1 2 Scott, John L. (December 24, 1961). "Berlin 'Judgment' Draws Jas, Neins". Los Angeles Times: Calendar, p. 4.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (December 20, 1961). "The Screen: 'Judgment at Nuremberg'". The New York Times: 36.

- ↑ "Judgment at Nuremberg". Variety: 6. October 18, 1961.

- ↑ "Film Review: Judgment at Nuremberg". Harrison's Reports: 166. October 21, 1961.

- ↑ Gill, Brendan (December 23, 1961). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker: 68.

- ↑ Coe, Richard L. (February 15, 1962). "'Nuremberg' Is Great Film". The Washington Post: D6.

- ↑ "Judgment at Nuremberg". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 29 (337): 19. February 1962.

- ↑ "Box office / business for Judgment at Nuremberg". IMDb. IMDb.com, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Amazon.com, Inc. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ "NY Times: Judgment at Nuremberg". NY Times. Retrieved 2008-12-24.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10". American Film Institute. 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ↑ AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies Nominees

- ↑ "Judgment at Nuremberg". MGM Home Entertainment. Beverly Hills, California: MGM Holdings. ASIN B0002CR04A. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Judgment at Nuremberg Blu-ray Hollywood Gold Series". blu-ray.com. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Judgment at Nuremberg Blu-ray Limited Edition". blu-ray.com. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ↑ Burke, Thomas (March 27, 2001). "Judgment at Nuremberg Theatre Review". Talkin' Broadway. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Judgment at Nuremberg |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Judgment at Nuremberg. |

- Judgment at Nuremberg on IMDb

- Judgment at Nuremberg at Rotten Tomatoes

- Judgment at Nuremberg at AllMovie

- Judgment at Nuremberg at the TCM Movie Database

- Judgment at Nuremberg at the American Film Institute Catalog

- 3 Speeches from the Movie with Text, Audio and Video from AmericanRhetoric.com