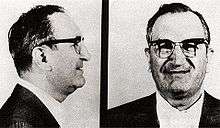

Joseph Bonanno

| Joseph Bonanno | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

January 18, 1905 Castellammare del Golfo, Sicily, Italy |

| Died |

May 11, 2002 (aged 97) Tucson, Arizona, U.S. |

| Other names | "Joe Bananas", "Don Peppino" |

| Citizenship | Italian and American |

| Known for | Boss of the Bonanno crime family |

| Criminal charge | Contempt of court[1] |

| Criminal penalty | 14 months |

| Criminal status | Released November 1, 1986[2] |

| Spouse(s) | Fay Labruzzo |

| Children | 3, including Salvatore "Bill" Bonanno |

Joseph Charles Bonanno Sr. (/bəˈnænoʊ/; January 18, 1905 – May 11, 2002) was an Italian-born American mafioso who became the boss of the Bonanno crime family.

Early life

Giuseppe Carlo Bonanno was born on January 18, 1905 in Castellammare del Golfo, a town on the northwestern coast of Sicily.[3] When he was three years old, his family moved to the United States and settled in the Williamsburg neighborhood in Brooklyn for about 10 years before returning to Italy. Bonanno slipped back into the United States in 1924 by stowing away on a Cuban fishing boat bound for Tampa, Florida with Peter Magaddino.[4] According to Bonanno, upon arriving at a train station in Jacksonville, Bonanno was detained by immigration officers and was later released under $1000 ($14,000 in 2018) bail. He was welcomed by Willie Moretti and an unidentified man, it was later revealed that Stefano Magaddino was responsible for bailing him out as a favour for Giovanni Bonventre, Bonanno's uncle. Bonanno first worked at a bakery owned by his uncle and later took up acting classes near Union Square, Manhattan. By all accounts, he'd become active in the Mafia during his youth in Italy, and he fled to the United States after Benito Mussolini initiated a crackdown.[4] Bonanno himself claimed years later that he fled because he was ardently anti-Fascist.[5] However, the former account is more likely, since several other Castellammarese mafiosi fled to the United States around the same time.[6]

Eventually, Bonanno became involved in bootlegging activities. He operated a distillery located inside an apartment building basement with Gaspar DiGregorio and Giovanni Romano, who was later killed in the distillery due to an accidental explosion. Sometime after 1926, Bonanno went to work for Salvatore Maranzano and supervised his distilleries in Upstate New York and Pennsylvania, he was also responsible for bailing out bootlegging associates from jail. During this time Bonanno admitted to carrying a pistol for the first time in the United States. He began to act as an enforcer for Maranzano and was part of his inner circle. In his book, Bonanno recalled an extortion attempt by Dominick "Mimi" Sabella, brother of Bonanno capo Michael Sabella and Philadelphia crime family boss Salvatore Sabella, where Sabella attempted to muscle his way into Bonanno's bootlegging operations. Bonanno made a gesture with his hand to represent a pistol and pretended to shoot Sabella in the head six times, although Sabella was part of Maranzano's crime family, Bonanno had the most authority and could not be reckoned with.[4]

The Castellammarese War

Almost from the beginning, Bonanno was recognized by his accomplices, especially Salvatore Maranzano, as a man with superior organizational skills and quick instincts; Bonanno immediately became a protege of Maranzano. He also became known to the leader of Mafia activities in New York, Joe "the Boss" Masseria. Masseria became increasingly suspicious of the growing number of Castellammarese in Brooklyn. He sensed they were gradually dissociating themselves from his overall leadership.

In 1927 violence broke out between the two rival factions that shortly developed into all-out war. This war between Masseria and Maranzano became known as the Castellammarese War. It continued for more than four years. By 1930, Maranzano's chief aides were Bonanno (as underboss and chief of staff),[7] Tommy Lucchese and Joseph Magliocco. Tommy Gagliano ran another gang that supported Maranzano. The Buffalo, New York mob boss Stefano Magaddino, another Castellammarese, also supported Maranzano, though Bonanno suspected that they were jealous of each other and had deep-seated hostilities towards each other. Magaddino's son was Peter Magaddino, a boyhood friend of Bonanno from his student days in Palermo. Masseria had Lucky Luciano, Vito Genovese, Joe Adonis, Carlo Gambino, Albert Anastasia and Frank Costello on his side.

However, a third, secret, faction soon emerged, composed of younger mafiosi on both sides. These younger mafiosi were disgusted with the old-world predilections of Masseria, Maranzano and other old-line mafiosi, whom they called "Mustache Petes." This group of "Young Turk" mafiosi was led by Luciano and included Costello, Genovese, Adonis, Gambino and Anastasia on the Masseria side and Profaci, Gagliano, Lucchese, Magliocco and Magaddino on the Maranzano side. Although Bonanno was more steeped in the old-school traditions of "honor", "tradition", "respect" and "dignity" than others of his generation, he saw the need to modernize and joined forces with the Young Turks.[6]

By 1931, momentum had shifted to Maranzano and the Castellammarese faction. They were better organized and more unified than Masseria's men, some of whom began to defect. Luciano and Genovese urged Masseria to make peace with Maranzano, but Masseria stubbornly refused. In the end, Luciano and Genovese concluded a secret deal with Maranzano. In return for safety and equal status for Luciano in Maranzano's new organization, Luciano and Genovese murdered Masseria and ended the Castellammarese War.[7]

Mob re-organization

After Masseria's death, Maranzano outlined a peace plan to all the Sicilian and Italian gang leaders in the United States. Under this plan, there would be 24 gangs (to be known as "Families") throughout the United States, each of whom would elect its own boss. In New York City, five Mafia families were established, headed by Luciano, Profaci, Gagliano, Vincent Mangano and Maranzano respectively. At the head of the whole organization would be the capo di tutti capi (the boss of all bosses), namely Maranzano. This final article of the plan did not please many of the gangsters, especially Luciano. As a consequence, Luciano arranged Maranzano's murder.[7]

Bonanno was awarded most of Maranzano's crime family. At age 26, Bonanno became one of the youngest-ever bosses of a crime family. Years later, Bonanno wrote in his autobiography that he did not know about the plan to kill Maranzano, but this is highly unlikely; Luciano would have almost certainly had him killed as well had he still been loyal to Maranzano. In any case, Bonanno had no interest in starting another gang war to avenge his predecessor and quickly reconciled with Luciano.[8]

In place of the capo di tutti capi in Maranzano's plan, Luciano established a national commission in which each of the families would be represented by their boss and to which each family would owe allegiance. Each family would be largely autonomous in their designated area, but the Commission would arbitrate disputes between gangs.[7] The purpose of this organization was to prevent another bloodletting like the Castellammarese War, and according to Bonanno, it succeeded. The establishment of the Commission ushered in more than 20 years of relative "peace" to the New York and national organized crime scene, and Bonanno wrote: "For nearly a thirty-year period after the Castellammarese War no internal squabbles marred the unity of our Family and no outside interference threatened the Family or me."

Bonanno was nicknamed "Joe Bananas" by the papers, a name he despised because it implied that he was crazy; his family was sometimes called "the Bananas family" after his nickname. A much safer nickname to use around him was "Don Peppino", a diminutive of his original Italian name.

Bonanno family

The Bonanno crime family's underbosses were Frank Garofalo and John Bonventre. While it was traditionally one of the smaller of the five New York families, it was more tight-knit than the others. With almost no internal dissension and little harassment from other gangs or the law, the Bonanno family prospered in the running of its loan sharking, bookmaking, numbers running, prostitution, and other illegal activities. In 1938, Bonanno left the country, then re-entered legally at Detroit so that he could apply for citizenship.

Bonanno's large cash position gleaned from crime allowed him to make many profitable real estate investments during the Great Depression. His legitimate business interests included areas as diverse as the garment industry (three coat factories and a laundry), cheese factories, funeral homes, and a trucking company.[7] It was said that a Joe Bonanno-owned funeral parlor in Brooklyn was utilized as a convenient front for disposing of bodies: the funeral home's clients were provided with double—decker coffins, and more than one body would be buried at once.[7] By the time Bonanno became a US citizen in 1945, he was a multi-millionaire.

Unlike most of his compatriots, Bonanno largely eschewed the lavish lifestyle associated with gangsters of his time. He preferred meeting with his soldati in his Brooklyn home or at rural retreats. He did, however, have a decided preference for expensive cigars.

The only encounter Bonanno had with the law during these years was when a clothing factory that he partly owned was charged with violating the federal minimum wage and hour law. The company was fined $50; Bonanno was only a shareholder in the company and was not fined. Government officials later arrested Bonanno, claiming he had lied on his citizenship application by concealing a criminal conviction; the charge was dismissed in court.

Despite this, Bonanno was all but unknown to the general public until the disastrous Apalachin Conference of 1957, which he was reported to have attended.[9] Called by Vito Genovese to discuss the future of Cosa Nostra in light of the intrigues that brought himself and Carlo Gambino to power, the meeting was aborted when police investigated the destination of the many out-of-state attendees' vehicles and arrested many of the fleeing mafiosi.[10] Bonanno claimed he skipped the meeting, but the attending capo Gaspar DiGregorio was carrying Bonanno's recently renewed driver's license; when DiGregorio was arrested at a roadblock he was misidentified as Bonanno.[11] An official police report instead lists him as being caught fleeing on foot.[12] Twenty-seven Apalachin attendees, including Bonanno, were indicted with obstruction of justice after refusing to answer questions regarding the meeting. Bonanno himself suffered a heart attack and was removed from the resulting trial, while the indictment and resulting convictions were ultimately thrown out.[12][13]

Personal life

In 1931, two months after Maranzano was murdered, Bonanno was married to Fay Labruzzo. They had three children: Salvatore "Bill" Bonanno (1932-2008); Catherine, born 1934; and Joseph Charles Jr. (1945-2005).

As he prospered, Bonanno bought property in Hempstead, Long Island and moved his family out of Brooklyn. When Bill was ten years old he developed a mastoid infection of his ear that led to his being transferred to a private boarding school in Tucson, Arizona. Bonanno and his wife would visit their son during the winter months. Eventually, Bonanno purchased a house in Tucson.

Plots and disappearance

By the mid 1950s, the Commission that had held the peace for so many years was unraveling. Vito Genovese and Frank Costello were fighting for control of the Luciano family. Vincent Mangano had mysteriously disappeared in 1951; by nearly all accounts he'd been murdered by Albert Anastasia, one of the most feared men in the syndicate. Anastasia took control of his family, but was gunned down in October 1957. Then in November the New York State Police raided the infamous Apalachin Meeting in rural Apalachin, New York. Dozens of capos – were captured and charged with various crimes. Then in 1963 Joseph Valachi, a soldier in the Genovese family, under indictment for murdering a fellow inmate, broke the code of omertà. Valachi described in detail the organizational structure of the Mafia, unmasked many of the leaders and recalled old feuds and murders. Although none of his testimony led to any actual prosecutions, it was nonetheless devastating to the mob.

After the death of Joe Profaci, a very good friend of Bonanno and leader of the Profaci crime family, he was succeeded by another good friend of Bonanno's, Joe Magliocco. Soon, Magliocco began to have troubles with the rebellious Joe Gallo and his brothers Larry and Albert, who were now backed by Lucchese and Gambino. Meanwhile, Bonanno was also feeling threatened by Lucchese and Gambino. The two then planned to have Gambino and Lucchese killed, as well as Bonanno's cousin Magaddino and Frank DeSimone in Los Angeles. Magliocco gave the contract to one of his top hit men, Joseph Colombo. However, Colombo betrayed his boss and went instead to Gambino and Lucchese. Gambino called an emergency meeting of the Commission. They quickly realized that Magliocco could not have planned this by himself. Remembering how close Magliocco (and before him, Profaci) had been with Bonanno, it did not take them long to conclude that Bonanno was the real mastermind.

At Gambino's suggestion, the Commission ordered Magliocco and Bonanno to appear for questioning. Bonanno did not show up, but Magliocco did and confessed. In light of Magliocco's failing health, the Commission imposed a very lenient punishment—a $43,000 fine and ordered him to hand over leadership of his family to Colombo. Soon, Magliocco was dead from high blood pressure. They intended to let Bonanno off easily as well, wanting to avoid a repetition of the bloodbaths of the 1930s.

Bonanno was already becoming unpopular with other Mafia bosses. For instance, Magaddino was incensed that Bonanno was moving in on Toronto, long considered part of the Buffalo family's territory. Some members of his family also thought he spent too much time away from New York, and more in Canada and Tucson, Arizona, where he had business interests. After several months with no response from Bonanno, they removed him from power and replaced him with one of his capos, Gaspar DiGregorio. Bonanno, however, would not accept this. This resulted in his family breaking into two groups, the one led by DiGregorio, and the other headed by Bonanno and his son, Salvatore. Newspapers referred to this as "The Banana Split."

In October 1964, Bonanno disappeared and was not heard from again for two years. Bonanno later claimed that he was kidnapped in front of his lawyer's apartment at 36 East 37th Street in New York City by Buffalo Family members, Peter Magaddino and Antonino Magaddino. According to Bonanno, he was held captive in upstate New York by his cousin, Stefano Magaddino. Supposedly Magaddino represented the Commission, and told his cousin that he "took up too much space in the air", a Sicilian proverb for arrogance. After six weeks, Bonanno was released and allowed to go to Texas. Although this account has long been accepted as part of Mafia lore, it is almost certainly false based on contemporary accounts of the time. For instance, it is not likely that Bonanno would have been walking the streets of New York unguarded, knowing that his fellow bosses had put a price on his head. Additionally, FBI recordings of New Jersey boss Sam "the Plumber" Decavalcante revealed that the other bosses were taken by surprise when Bonanno disappeared, and other FBI recordings captured angry Bonanno soldiers saying, "That son-of-a-bitch took off and left us here alone."[14]

Bonanno's hold on his family had become tenuous in any event, however. Many family members complained that Bonanno was almost never in New York and spent his time at his second home in Tucson.[15] He was also facing pressure from U.S. Attorney Robert Morgenthau, who had served him with a subpoena to testify before a grand jury investigating organized crime. The first round of questioning was to start on the day after he disappeared. Bonanno thus faced two bad choices—testify and break his blood oath, or refuse and be jailed for contempt of court.[14]

The Bonanno War

What is beyond dispute is that Bonanno resurfaced in May 1966 at Foley Square, claiming he'd been kidnapped. He was indicted for failing to appear before the grand jury, but challenged it for five years until the charge was dismissed in 1971.[7]

Unwilling to accept the loss of his family, Bonanno rallied several members of his family behind him. The family split into two factions, the DiGregorio supporters and the Bonanno loyalists. The Bonanno loyalists were led by Bonanno, his brother-in-law Frank Labruzzo and Bonanno's son Bill. There was no violence from either side until a 1966 Brooklyn sit-down. DiGregorio's men arrived at the meeting, and when Bill Bonanno arrived a large gun battle ensued. DiGregorio's loyalists planned to wipe out the opposition but they failed and no one was killed.[15] Further peace offers from both sides were spurned with the ongoing violence and murders. The Commission grew tired of the affair and replaced DiGregorio with Paul Sciacca, but the fighting carried on regardless.

The war was finally brought to a close with Joe Bonanno, still in hiding, suffering a heart attack and announcing his permanent retirement in 1968.[15] He also promised to never involve himself again in New York Mafia affairs. After considerable debate, the Commission accepted Bonanno's offer, in view of his status as a Mafia elder statesman. However, they stipulated that if Bonanno broke his promise, he would be killed on the spot.[7] Both factions came together under Sciacca's leadership, though the family would need almost a quarter-century to recover the prominence and wealth it had enjoyed under Bonanno. His replacement was Natale "Joe Diamonds" Evola as boss of the Bonanno family. Evola's leadership was short lived - his death (from natural causes) in 1973 brought Philip "Rusty" Rastelli to the throne.

Later career in Arizona [3]and California

Bonanno and his son subsequently moved to Arizona, where he was at one time sent to federal prison to serve time for various offenses during his previous stay in that state.

In the late 1970s, his two sons, Salvatore and Joe Jr., brought high heat[16] in Northern California after getting involved with Lou Peters, a Cadillac-Oldsmobile dealer, in San Jose, Lodi and Stockton. As Joe Jr. grew up, Bonanno Sr. laundered his ill-gotten millions through legitimate businesses, many of them in California. In 1977, Salvatore approached the owner of a Lodi Cadillac–Oldsmobile dealership, Louis E. Peters, with an offer to buy him out for $2 million, in which the dealership was valued around $1.2 million. The Bonannos planned to purchase a string of 13 Central Valley car dealerships and launder mob money. Peters would remain a front man. But Peters decided to help take Bonanno Sr. down. Peters turned into an undercover for the FBI, becoming the Bonannos' friend, taping conversations, even staying at Bonanno's Tucson home. After a paranoid Peters saw Bonanno's nephew flirting with his daughter, he moved to an apartment in Stockton, even having Bonanno stay there for three days. Instead, the FBI hit Bonanno with an indictment alleging he obstructed a San Jose grand jury investigation into his California assets. Peters provided key insider testimony. A federal judge smacked the 75-year-old Bonanno with his first felony conviction. Bonanno got five years. Owing to his poor health, he served one.[17]

Despite an arrest record dating back to the 1920s, Bonanno was never convicted of a serious crime. He was once fined $450 and held in contempt of court for refusing to testify in 1985.[1] Assigned federal inmate number 07255-008, he was transferred from the Federal Correctional Institution in Tucson, Arizona to the U.S. Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri due to ill health at his advanced age and released on November 1, 1986.[2] Upon retirement, he was allowed to live at home in the Catalina Vista neighborhood of Tucson, Arizona with his family.

During Salvatore Bonanno's trial, he gave interviews to author Gay Talese that formed part of the basis of his 1971 true crime book Honor Thy Father. Joseph Bonanno was initially infuriated at the book and refused to speak to Salvatore for a year.[18] By the late 1970s, however, Bonanno's attitude had changed; he had become interested in writing an autobiography to offer his own take on his life.[19] Bonanno's book was published in 1983 as A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno. The government seized the opportunity and questioned him about the Commission, hoping to prove its existence given that he spoke about it in his book. Technically, Bonanno kept the vow of omertà and answered no questions in government hearings.

Bonanno justified his decision to write A Man of Honor on the grounds that omertà represented a lifestyle and tradition greater than the code of silence it is generally understood to be: as he had not been compelled to reveal his secrets by becoming an informant or government witness, Bonanno reasoned, he did not violate his code of honor.[19] Other New York Mafia leaders were nevertheless outraged by his revelations, and considered it a flagrant violation of omertà. Gambino boss Paul Castellano, Lucchese underboss Salvatore Santoro and Lucchese capo Salvatore Avellino were all caught on tape expressing their horror and outrage that Bonanno discussed the existence of the Commission, with Avellino complaining "What is he trying to prove, that he's a man of honor? [...] [H]e actually admitted [...] that he was the boss of a family."[20] Joseph Massino, who took over Bonanno's family in 1991, was equally disgusted by the book, bluntly telling his colleagues that Bonanno had "disrespected the family by ratting." He was so outraged and embarrassed by it that he renamed the family "the Massino family".[21] Nevertheless, Massino himself later became a government witness, and the "Massino" family name never caught on outside the family.

Bonanno's editor for A Man of Honor was publisher Michael Korda who said of Bonnano, "In a world where most of the players were, at best, semiliterate, Bonanno read poetry, boasted of his knowledge of the classics, and gave advice to his cohorts in the form of quotes from Thucydides or Machiavelli."[22]

In April 1983, Joseph Bonanno and his son, Bill Bonanno appeared on the CBS News TV program 60 Minutes to be interviewed by correspondent Mike Wallace.[23]

Bonanno died on May 11, 2002, of heart failure at the age of 97. He is buried at Holy Hope Cemetery & Mausoleum in Tucson.[24]

In popular culture

In 1991, Bonanno's daughter-in-law, Rosalie Profaci Bonanno, published the memoir Mafia Marriage: My Story. This book was eventually converted to the 1993 Lifetime network film Love, Honor, & Obey: The Last Mafia Marriage. Bonanno was portrayed by Ben Gazzara.[25]

In the 1991 film Mobsters, Joe Bonanno is portrayed by actor John Chappoulis.[26]

In 1999, the Lifetime TV network produced a biographical film called Bonanno: A Godfather's Story. The film chronicles the rise and fall of organized crime in the United States. Bonanno was portrayed by Martin Landau.[27]

In 2004, Joe's daughter-in-law began putting Joe's personal items up for auction on eBay. This continued until 2008.[28]

In 2006, episode 66 of The Sopranos, "Members Only", Eugene Pontecorvo wants to retire and uses Joe Bonanno as an example of a retired mob member.[29] [30] Also in episode 76, "Cold Stones", Tony mentions that "Joe Bananas" went to war against Carlo Gambino for seven years.

In 2009, Joe's cousin, Thomas Bonanno, participated as a Mafia expert in the filming of Deadliest Warrior: "Mafia vs. Yakuza", demonstrating his skills and marksmanship with a Thompson submachine gun as well as talking about "true" Sicilian Mafia philosophy and culture.[31]

In 2014, Eldorado the last episode of the final season of Boardwalk Empire, Joe Bonanno played by Amadeo Fusca has a non-speaking cameo role. He is seen sitting at the table as Lucky Luciano gathers the country's most powerful crime bosses and forms The Commission.[32]

Notes

- 1 2 "Bonanno flown to federal prison". The Deseret News. September 7, 1985. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- 1 2 "Inmate Locator: Joseph C Bonanno". Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- 1 2 "Former Mob Big Bonanno Dies". Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- 1 2 3 Raab, Selwyn. Five Families. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2005. Print.

- ↑ Raab, Selwyn (May 12, 2002). "Joe Bonanno Dies; Mafia Leader, 97, Who Built Empire". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- 1 2 Sifakis, Carl (1987). The Mafia Encyclopedia. New York City: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-1856-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The Five Families. MacMillan. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ↑ Bonanno, pp. 140-141

- ↑ Bonanno, p. 217

- ↑ Raab, pp. 117-118

- ↑ Bonanno, p. 216

- 1 2 Raab, pp. 119-120

- ↑ Bonanno, p. 222

- 1 2 Raab, pp. 165-166

- 1 2 3 Bonanno, Joe A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno. New York: St Martin's Paperbacks., 1983. ISBN 0-312-97923-1.

- ↑ "In a Daring Undercover Scam, a California Car Dealer Helps Trap Mob Kingpin Joe Bonanno". People. October 6, 1980.

- ↑ "A local angle on notorious mafia boss". The Record. November 16, 2005.

- ↑ Bonanno, pp. 342-343

- 1 2 Bonanno, pp. 381-385

- ↑ Davis, John H. (1993). Mafia Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the Gambino Crime Family (1994 paperback ed.). New York: HarperCollins. pp. 231–234. ISBN 978-0-06-109184-1.

- ↑ Raab, pp. 637, 639

- ↑ Korda, Michael (1999). Another life : a memoir of other people (1st ed.). New York: Random House. pp. 415–425. ISBN 0679456597. OCLC 40180750.

- ↑ "2002: Joe Bonanno". CBS News. March 28, 2011.

- ↑ Great Graves of Upstate New York

- ↑ Love, Honor & Obey: The Last Mafia Marriage (TV 1993)

- ↑ Mobsters (1991)

- ↑ Bonanno: A Godfather's Story (TV 1999)

- ↑ "Mob ties just a few clicks away" Tucson Citizen

- ↑ "Sopranos script" Springfield! Springfield!

- ↑ "No Retiring from This" American Popular Culture

- ↑ "Thomas Bonanno". IMDb. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ↑ Boardwalk Empire

References

- Bonanno, Joseph (1983). A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno (2003 ed.). New York: St. Martin's Paperbacks. ISBN 0-312-97923-1.

- Raab, Selwyn (2005). Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-36181-5.

Further reading

- Talese, Gay (1971). Honor Thy Father. Cleveland: World Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8041-9980-9

- Crittle, Simon, The Last Godfather: The Rise and Fall of Joey Massino Berkley (March 7, 2006) ISBN 0-425-20939-3

- DeStefano, Anthony. The Last Godfather: Joey Massino & the Fall of the Bonanno Crime Family. California: Citadel, 2006.

| American Mafia | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Salvatore Maranzano |

Bonanno crime family Boss 1931–1965 |

Succeeded by Gaspar DiGregorio |

| Preceded by Vito Genovese as boss of bosses |

Capo di tutti capi Chairman of the commission 1959–1962 |

Succeeded by Carlo Gambino as boss of bosses |