John FitzWalter, 2nd Baron FitzWalter

John FitzWalter, 2nd Baron FitzWalter (also Fitzwalter[1] or Fitz Wauter[2]) (c. 1315–18 October 1361)[3][note 1] was a member of the early-14th-century English baronage and a prominent Essex landowner. The FitzWalter family was of a noble and ancient lineage, with connections to the de Clare family, who had arrived in England at the conquest. The FitzWalters held estates all over Essex, as well as properties in London and Norfolk. FitzWalter played a prominent role in Edward III's wars in France, and he also made a good marriage to the daughter of Lord Percy. However, FitzWalter is best known for his criminal activities in Essex, particularly around Colchester. He had gathered an affinity from leading members of the county's gentry to him, and, with their support waged an armed campaign against his Colchester neighbours from almost from the moment he reached adulthood. The townsmen seem to have exacerbated dispute by illegally entering FitzWalter's park in Lexden; in return, FitzWalter banned them from one of their own watermills and then, in 1342, he besieged the town, preventing anyone entering or leaving, as well as ransacking much property. One historian has described him, in his activities, as the medieval equivalent of a 20th-century American rackateer.

FitzWalter intermittently returned to France and the war, but notwithstanding his royal service, he never held office in his county, and this has been put down to his defiance of the King's peace and his usurpation of the royal authority there. FitzWalter was too powerful, and too aggressive in defence of his rights, for the local populace to confront him legally, and it was not until 1341 that FitzWalter was finally brought to justice. The King despatched a royal commission to Chelmsford to investigate a brought range of social ills, among which was FitzWalter and his gang. Although most of them received little or no punishment, FitzWalter did not escape: arrested and sent to London, he was immediately imprisoned. He languished n the Tower of London for over a year until the King agreed to release him and restore FitzWalter to his estates. This was on condition that he buy them back off the King for the immense sum of over £800. FitzWalter died in 1361—still paying off his fine—leaving a son, Walter, as his heir.

Early life

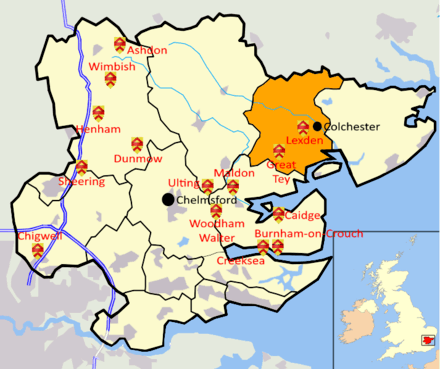

The FitzWalter family was a wealthy and long-established family in the north-Essex area.[1] Descended from the conquest-era Lords of Clare, the family estates were concentrated around the lordship of Dunmow.[4] They also held estates as distant as Henham, to the west of the county, Woodham to the southeast,[5] Chigwell to the southwest,[6] Diss in Norfolk,[7] and Castle Baynard in London.[4][note 2] John FitzWalter was (probably the only) son of Sir Robert FitzWalter and Joan, daughter of Thomas, Lord Moulton.[1] The family has been been described as "warlike as well as rich" even before FitzWalter was born: his ancestor, also Robert, had been a leading rebel against King John the preceding century.[8]

John FitzWalter was around 13 years old when his father died in 1328,[3] and a recent biographer has suggested that FitzWalter was raised by his widowed mother. This may have resulted in his becoming "a difficult and dangerous adult".[1] Although by law he could not receive his inheritance until he was 21, in the event, King Edward III allowed him to enter into his estates and titles slightly early, in 1335, when FitzWalter was about 20.[3]

FitzWalter received livery of two-thirds of his inheritance, with the remainder held by his mother as her dower. This, says Christopher Starr, "represented a significant slice of the FitzWalter estate", and may have led to his later criminal behaviour.[1] FitzWalter's grandfather, Robert, had transferred fine land in 1275 to help found Blackfriars Abbey in London, but had reserved his rights to certain properties in the city. This reservation was successfully challenged by the city, and both Robert and John made repeated attempts to assert their claim. According to John Stow, the last time the latter in 1347, was "peremptorily"[9] refused by the Mayor and Common Council.[9]

However, he was still a prominent Essex estate holder,[10] and, suggests Harris, "with youth, power and wealth, FitzWalter was the 'rich kid' of his day".[10]

Career

In 1337 the King of France, King Philip, confiscated the Duchy of Aquitaine, then an English royal possession. In response, King Edward claimed the French throne and invaded France.[11] In December the following year, utilising the "untapped pools of genteel manpower" among the youth of his aristocracy, the King summoned FitzWalter and 43 other knights to Ipswich, armed and ready for military service in France.[10] FitzWalter joined the retinue[3] of the recently-created Earl of Northampton.[12]

FitzWalter became a notable soldier of Edward III's early campaigns,[5] and he periodically returned to France over the following years.[1] In 1446 he served with the Prince of Wales[3] at theSiege of Calais.[13] FitzWalter indentured to serve for six months at a wage of100 marks. For this he brought the Prince 20 men-at-arms (himself, four other knights and 15 esquires) and 12 archers.[13]

FitzWalter frequently returned to England for parliaments.[1] He had been first summoned as Johannes de fitz Wauter in 1340, and was to attend every sitting until 1360.[14] He was also a royal councillor, having been appointed in 1341 and serving in that capacity until 1358.[14] In 1342 FitzWalter was one of 250 knights to take part in a great tournament held at Dustable,[15] as did FitzWalter's late accomplice Sir Robert Marny.[16] At some point in his career, FitzWalter married Eleanor, second[17] daughter of Henry Percy, Lord Percy.[14] They had at least two children, Walter, his heir, and a daughter Alice (d. 11 May 1400),[18] who later married Aubrey de Vere, 10th Earl of Oxford,[19] possibly, though, not for many years after FitzWalter's death.[18]

Criminal career

A recent commentator has described FitzWalter as being of "good family and great possessions, but nonetheless a familiar racketeer type".[21] It has been suggested that for many men of his generation, experience on the Scottish and then French fronts could have exacerbated a "natural appetite for again and intimidation".[10] Furthermore, Essex had been at the forefront of the Gascon campaigns of the late-13th century, and by the early 14th century was a highly militarized society.[22]

These factors, says Starr, undoubtedly contributed to FitzWalter's increasingly violent behaviour in Essex,[1] and by 1340 he was launched on a career of crime. That year he took part in a mass-assault on John de Segrave's manor in Great Chesterford. FitzWalter was in a gang of over 30 men led by the Earl of Oxford. Segrave later reported that FitzWalter and his associates "broke his park...hunted therein, carried away his goods and his deer from the park, and again his men and servants".[10]

FitzWalter gathered an affinity of prominent local gentry around him. They included such figures as Lionel Bradenham[note 3]—steward of FitzWalter's Lexden manor, and who held the manor of Langenhoe off him for knight's service[25]—and Robert Marney.[1] Marney, like FitzWalter, was a seasoned soldier from the French wars and something of a gangster in his own right.[10][note 4] With the support of powerful and influential men such as these, FitzWalter was to earn himself "a considerable reputation...as a thug of the first order",[10] wrote Gloria Harris, as the most feared gang leader in Essex.[10]

The names of many of FitzWalter's gangsters are known to historians by the survival of their later indictments. They include Walter Althewelde, William Baltrip, John Brekespere, John Burlee, John Clerke, Thomas Garderober, William Saykin, Roger Scheep, John Stacey and William de Wyborne.[26] Another, known only as Roger, was the parson of Osemondiston.[27][26][note 5] In return for furthering FitzWalter's causes, his retainers could expect his full protection: on at least one occasion he broke one of his men out of Colchester gaol before he could be brought before the justices.[31] FitzWalter's man, Wymarcus Heirde, had been attached and imprisoned at the Berestake by the bailiffs of Colchester. Before he could be adjudged, however, FitzWalter despatched "Simon Spryng' and others" to forcibly free Heirde.[28]

The later indictments list FitzWalter's litany of crimes. He took illegal distraints. He behaved as he liked "to his poor neighbours, because no sheriff or bailiff dared to free any distraint which he had taken, be it ever so unjust".[32] He also indulged in extortion. On one occasion he extorted 100 shillings from two men in Southminster.[32] On another, FitzWalter persuaded one Walter of Mucking to transfer lands worth £40 to FitzWalter, for which FitzWalter was to pay Walter an annual rent of £22. FitzWalter also pledged to provide Walter with luxurious robes and tunics in kind. In the event, FitzWalter not only paid hardly any rent but also refused to hand over the clothes that he had promised. Walter dared not take legal action against FitzWalter.[28] Few men did. For example, Richard de Plescys,[33] Prior of Dunmow Abbey, was intimidated into storing and looking after a cart and horses of FitzWalter's, at the prior's expense. The prior did not report him,[34] despite the fact that the priory, at least in theory, enjoyed the King's personal protection.[35][note 6] FitzWalter later despatched his henchman Baltrip to forcibly and illegally amerce and distrain the prior.[38]

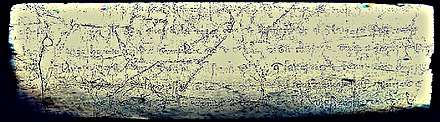

National Archives manuscript JUST 1/266

Cattle Rustling was an important pastime of the FitzWalter gang. They seized cattle from Colchester's main monastic house, the Priory of St. John, for which FitzWalter was condemned as "a common destroyer of men of religion".[32] He either had these animals worked to death or left them to starve.[40] For two years, he also illegally pastured his own sheep and cattle on common land used by the town's Burgesses, because the land abutted his own Lexden Park.[28][note 7]

Killings occasionally took place also. In 1345, one Roger Byndethese was sentenced at Waltham to abjuration of the realm had to carry a large cross from Waltham to Dover. He was not to reach it: intercepted by FitzWalter's men outside Waltham, they—claiming to act "under the banner of God and of Holy Church", but certainly at the command of Lord John[28]—summarily beheaded Byndthese.[28]

Larceny was much favoured.[32] One method was to force men to enfeoff FitzWalter and his band with their possessions, who would then have to be paid off before returning the goods.[43] Similarly, FitzWalter confiscated sacks of wool from a Burnham-on-Crouch merchant which they refused to return until he paid them a substantial sum. FitzWalter and his men had no compunction about taking all the fish, meat and victuals they wanted from Colchester market, "at their will, to the oppression of the whole market",[28] and generally violating the town's rules of trade in and outside of the marketplace.[44] Such was the fear that local people held FitzWalter in, that when he refused to pay what he had been assessed for a royal tax, the "men of the villages paid for him to their great impoverishment".[28] He had, after all, threatened to break the legs and arms ("tibia et bracchia")[28] of anyone who opposed his doing so, and more, would leave them to die.[28]

Siege of Colchester

The FitzWalters had long had turbulent relations with their Colchester neighbours.[note 8] In 1312, townsmen and merchants had broken into Lexden Park and hunted John FitzWalter's father's deer. The principal causes of antagonism between the two parties were over pasture rights, and the jurisdiction of Colchester borough in Lexden, particularly the extent to which FitzWalter's tenantry in the latter could be taxed by the Burgesses of the former.[45] There was also repeated friction over a watermill adjacent to FitzWalter's Lexden Park. Although owned by Colchester men, FitzWalter objected to the presence of any men from the town near his property and refused them entry to their own mill for over six months. The townspeople later complained that, although FitzWalter had eventually offered to buy it from them, "Lord John has not paid for it and still keeps it".[28] Further, in order to ensure a constant supply of water for his mill, FitzWalter extorted another watermill in nearby West Bergholt from one of the townsmen as a backup.[46]

FitzWalter's grievances against the men of Colchester may not have been without foundation. In 1342, claimed FitzWalter, Colchester men had invaded Lexden Park,[1] in an attempt to assert their own perceived rights[47] of pasturing, hunting and fishing there. Richard Britnell has highlighted how "on this issue feelings ran sufficiently high for large numbers of burgesses to take the law into their own hands; pasture riots are more in evidence than any other form of civil disturbance" in Essex at this time.[44] Britnell also notes, though, that it is unlikely that there were any rights to common pasture on the Lexden estate.[48] FitzWalter petitioned the King that about 100 Colchester men had, in the course of their trespass, "broke [FitzWalter's] park at Lexden, hunted therein, felled his trees, fished in his stews, carried away the trees and fish as well as deer from the park and assaulted his servant John Osekyn there, whereby he lost his service for a great time".[49] Lexden Park was one of FitzWalter's most valuable possessions, consisting of over 150 acres (61 hectares) of pasture,[50] which in 1334 had been valued for tax purposes as being worth over £1300.[51] In July a commission of Oyer and Terminer was sent to Essex to investigate FitzWalter's accusations.[49]

A crisis point was reached when one of FitzWalter's men was killed in Mile End during the attack on Lexden Park.[52] According to law, an inquest was held, but FitzWalter disputed the findings of the town's coroner. Instead—and in breach of the borough's liberties which allowed it to administer its own internal affairs—FitzWalter brought in the county coroner[45] (probably one of his own retainers)[38] to perform another inquest. Neither inquest, however, appears to have satisfied the parties involved.[45] FitzWalter attempted to have a bailiff of Colchester, John Fordham, indicted for the death, but to no avail.[52]

FitzWalter reacted violently. He was doubtless motivated at least in part by the earlier attack on Lexden by the men of Colchester.[50] Now he proceeded to hunt down members of both juries and assault them. FitzWalter's first victim was Henry Fernerd of Copford, a juryman who had publicly expressed his faith in Fordham's innocence. FitzWalter's men beat him nearly to death.[8] FitzWalter soon widened his attacks to the men of Colchester generally, attacking them as far afield as Maldon and Southminster. FitzWalter then escalated his attacks on individuals to the town itself, and on 20 May 1342 placed Colchester under siege.[45] FitzWalter ambushed anyone caught entering or leaving the town, "until no man can go to a market or fair from Easter until Whitsuntide".[32] FitzWalter and his men armed themselves further with lumps of wood from the broken doors and roof beams of houses they had already destroyed.[10] His physical campaign against the townsmen was accompanied by legal attacks, in which he attempted to fix juries against them.[38] FitzWalter's siege lasted until 22 July, when the burghers paid FitzWalter £40 compensation. This does not appear to have brought peace between them, however, as FitzWalter again besieged the town from 7 April to 1 June the following year; this may have been provoked by continuing attacks on Lexden Park. The town paid FitzWalter another £40 for him to lift the siege;[45] another consequence of his campaign of violence was that Colchester juries were too afraid to bring verdicts against him or his men.[52] FitzWalter was fully supported by his affinity, and, indeed, the latter often carried out their own social quasi-independent operations. For example, in 1350 Bradenham himself besieged Colchester for three months[45] in Autumn 1350.[53]

Indictment

Elizabeth C. Furber

Essex, Jennifer Ward has written, "suffered severely" from the FitzWalter gang's activities throughout the 1340s. It was difficult for justice to be done, however, and was to take nearly ten years.[55] On the other hand, it is equally likely that, having usurped the position of the King's writ in the north of the county, FitzWalter was in a position to keep the peace, albeit in his own fashion:[56] this had been described as a "rival system of justice"[57] to that of the King's.[57] FitzWalter's expeditions to France—thus removing him from the theatre of conflict—were probably attempts by King Edward at solving the problem without taking legal action.[27][note 10] This was an impermanent solution, however, and eventually, in response to FitzWalter's continuing outrages,[1] a Commission of the peace, probably under the authority of William Shareshull, was dispatched to Chelmsford early in 1351.[60][note 11] As a result, says Furber, "justice, of a sort, finally caught up"[28] with FitzWalter.[62] Shareshull's commission indicted FitzWalter for failing to appear in answer to accusations of felony.[3] He was judged guilty of various serious crimes, such as extortion and refusal pay taxes,[63] even though he had intimidated the tax assessor into rating him for the lowest amount possible.[28] His fundamental offence, says Ward, was his "encroaching on the royal power" in the county.[63] FitzWalter's indictment roll, says Margaret Hastings, listed so many offences that the judicial roll "read like an index to the record of indictment for a whole county".[21][note 12] On 31 January 1351, the King summoned FitzWalter by a writ of capias and he appeared before the King's Bench at Westminster Palace, and following which he was cast into the Marshalsea Prison[62] and his estates confiscated.[3] In November FitzWalter was transferred to the Tower of London, where he was allocated ten shillings a day from his estates for his subsistence.[62]

FitzWalter's associates were also convicted. Marney and Bradenham were imprisoned and fined (and later released) with him.[63] The parson was forced to give up his benefice. Others were either pardoned—in at least one case following military service in Brittany—or exigented.[26] Some were exonerated outright.[27] Only one minor member of the gang, William de Wyborne,[26] was hanged for his crimes; his chattels—worth 40d—were confiscated.[26]

FitzWalter was imprisoned for a year,[27] and following his release in June 1352, the King pardoned him. The pardon was a substantial document, and covered murder, robbery, rape, arson, kidnapping, trespass, extortion and incitement, and ranged from thefbote[note 13] and illegally carrying off other's rabbits to the usurpation of royal justice.[62]

FitzWalter had also been bound to pay the King the "colossal"[1] amount of at least £847 2s 4d.[26][note 14] He paid this off incrementally,[1] effectively buying his estates back from the King.[27] Indeed, the size of the fine—which he spent the last decade of his life paying—is probably the only reason his estates were returned to him in the first place.[21] For ten years, comments Hanawalt, the Pipe rolls "benignly enter payments to the king from his 'dear and faithful' John FitzWalter".[68]

Later life

Probably as a direct consequence of his violent behaviour in Essex, and although he sat in parliament and on the King's council, he never held royal office in the county, and nor was he appointed to any of its commissions.[1]

FitzWalter died on 18 October 1361; he was buried alongside his wife in Dunmow Priory.[14] Eleanor had predeceased him,[14] although not, apparently, by long.[1] On the day of his death, there was still one farthing owed to the crown from his fine a decade earlier.[1] He was succeeded in his estates and titles by Walter, who had been born in 1345 ("at the height, says Starr, "of his father's criminal activities"),[1] and who, unlike his father, was to be a loyal servant of the crown and play an important role in suppressing the Peasants' Revolt in Essex in 1381.[69] He was also to be a close ally of his brother-in-law the Earl of Oxford in the politically turbulent years towards the end of King Richard II's reign.[18]

In the criminal activities and disregard for the law demonstrated by men such as John FitzWalter, wrote Elisabeth Kimball, "the lack of governance associated with fifteenth-century England seems to have had its roots in the fourteenth".[60]

Notes

- ↑ Cokayne is non-specific about FitzWalter's precise date of birth, merely stating that he was "aged 13 and more at his father’s death".[3]

- ↑ The FitzWalter family held 13 manors in Essex: Ashdon, Burnham-on-Crouch, Caidge, Creeksea, Little Dunmow, Henham, Lexden, Maldon, Sheering, Great Tey, Ulting, Wimbish and Woodham Walter.[7]

- ↑ Badenham has been described as "no common criminal [being] a successful and innovative farmer, a lawyer legal adviser" who—unlike FitzWalter—had sat on royal commissions in Essex.[23] Although described by Furber as a "doubtful character" on account of his association with FitzWalter, he was not indicted in 1351.[24]

- ↑ Marney had taken part in a major operation—possibly over the course of several days—against the Earl of Northampton's Essex estates in 1342. During this attack, he and about ten others had systematically raided, damaged, and stole from seven of the earl's parks in diverse parts of the county.[10]

- ↑ Osemondiston, later called Osmondston, was a village in FitzWalter's manor of Diss, on the River Waveney.[28] It was also known as Scole, by which name it is known today. [29][30]

- ↑ The protection was reiterated in November 1451 as a result of what the Calendar of Patent Rolls describes as the "wretched depression to which the priory of Dunmow is subjected through the willful injuries and damages of men of those parts scheming to destroy the said priory".[36][37]

- ↑ A remnant of FitzWalter's Lexden Park is still extant today (51°53′20.7″N 0°51′53.9″E / 51.889083°N 0.864972°E). Covering slightly over 8 hectares (80,000 m2), it lies to the south of Lexden Road, between Church Lane and Fitzwalter (sic) Road.[41] The vast majority of the Park in Fitzwalter's day was to the north of the road.[42]

- ↑ W. R. Powell has explained this historical tension by the transformation of Colchester, by the 14th century, into "one of the most important towns in eastern England. Under a series of royal charters, from 1189 onwards, the burgesses had secured a degree of self-government, including the right to hold a hundred court for the town and its liberty (or suburbs), certain hunting rights in the liberty, and a monopoly of fishing in the River Colne. But the earlier charters had been loosely drafted, and disputes often arose concerning the burgesses' jurisdiction over the manors within the liberty, and over the river."[8] The dispute between the burgesses and the FitzWalters, he suggests, specifically arose because the borough had claimed Lexden since Saxon times, but their claims had been put aside after the conquest.[8]

- ↑ This proverb is found in the 15th-century British Library Add. MS 41321, folio 86.[54]

- ↑ Recruiting offenders for military service was a common strategy of Edward III, as he both gained a soldier at the same time as removing a troublemaker from their region.[58] The men would often be pardoned on their return, however, and as such the practice was unpopular with contemporaries: petitions had been submitted to parliament in 1328, 1330, 1336 and 1340 against it.[59]

- ↑ This was necessary because of endemic corruption within the King's Bench then sitting at Chelmsford.[61] Shareshull's commission was to remain there until 1361, and particularly focused on the enforcement of labour laws.[60] As a result of its lengthy tenure, it raised fines from 7,500 individuals, which amounted to over one in ten of the adult Essex populace.[21]

- ↑ FitzWalter's indictment roll is held at the National Archives in Kew, classified as JUST 1/266.[64][39] The FitzWalter gang's portion of the indictments consists of three membranes, probably the raw notes taken contemporaneously—"the clerk probably had no time to recopy them"[64]—and written in French. They are marked on the dorse as having been taken at Chelmsford in 1351 and forwarded Coram Rege the same year.[65]

- ↑ Merriam-Webster defines thefbote, in middle English and Scots law as the "the offense of agreeing to receive stolen goods or a compensation from a thief whether by the owner by way of composition or by a judge as an inducement for conniving at the escape of the thief from punishment".[66]

- ↑ However, Furber points out that it is difficult to establish the precise amount demanded by the crown, "as there are numerous small amounts on the Pipe Rolls" which may or may not be connected to FitzWalter. The figure provided is the sum of all the major payments he is certain to have paid and is thus a minimum.[67]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Starr 2004.

- 1 2 National Archives 1348.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cokayne 1926, p. 476.

- 1 2 Furber 1953, p. 61.

- 1 2 Starr 2007, p. 19.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 20 n.2.

- 1 2 Moore 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Powell 1991, p. 68.

- 1 2 Stow 1908, p. 279.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Harris 2017, pp. 65–77.

- ↑ Curry 2003, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Ormrod 2004b.

- 1 2 Furber 1953, p. 61 n.3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cokayne 1926, p. 477.

- ↑ Ayton 1999, p. 33.

- ↑ Ayton 1999, p. 33 n.43.

- ↑ Hutchinson 1778, p. 218.

- 1 2 3 Goodman 2004.

- ↑ Leese 1996, p. 218.

- ↑ Sayles 1988, p. 453.

- 1 2 3 4 Hastings 1955, p. 347.

- ↑ Thornton & Ward 2017, pp. 1–26.

- ↑ Phillips 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 181 n.2.

- ↑ Round 1913, p. 86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Furber 1953, p. 65.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hanawalt 1975, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Furber 1953, p. 63.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 83 n.1.

- ↑ Blomefield 1805, p. 130.

- ↑ Hanawalt 1975, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Furber 1953, p. 62.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 82 n.6.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 44.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 45.

- ↑ C. P. R. 1907, p. 136.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 83 n.2.

- 1 2 3 Furber 1953, p. 46.

- 1 2 National Archives 1351.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 43.

- ↑ Google 2018.

- ↑ Cromwell 1826, p. 238.

- ↑ Hanawalt 1975, p. 14 n.32.

- 1 2 Britnell 1986, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 V. C. H. 1994, p. 22.

- ↑ V. C. H. 1994, pp. 259–264.

- ↑ Cohn & Aiton 2013, p. 195.

- ↑ Britnell 1988, p. 161.

- 1 2 Furber 1953, p. 88 n.1.

- 1 2 Britnell 1988, p. 164.

- ↑ Ward 1998, p. 119.

- 1 2 3 Powell 1991, p. 69.

- ↑ Round 1913, p. 89.

- ↑ Owst 1933, p. 43.

- ↑ Ward 1991, p. 16.

- ↑ Hanawalt 1975, p. 14.

- 1 2 Scattergood 2004, p. 152.

- ↑ Bellamy 1964, pp. 712–713.

- ↑ Aberth 1992, p. 297.

- 1 2 3 Kimball 1955, p. 279.

- ↑ Putnam 2013, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 4 Furber 1953, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 Ward 1991, p. 23.

- 1 2 Furber 1953, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 12.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster 2018.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 65 n.1.

- ↑ Hanawalt 1975, p. 10.

- ↑ Furber 1953, p. 10.

Bibliography

- Aberth, J. (1992). "Crime and Justice under Edward III: The Case of Thomas De Lisle". The English Historical Review. 107: 283–301. OCLC 2207424.

- Ayton, A. (1998). "Edward III and the English Aristocracy at the Beginning of the Hundred Years War". In Strickland, M. Armies, Chivalry and Warfare in Medieval Britain and France. Harlaxton Medieval Studies. VII. Stamford: Paul Watkins. pp. 173–206. ISBN 9-781-87161-589-0.

- Ayton, A. (1999). Knights and Warhorses: Military Service and the English Aristocracy Under Edward III. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-739-9.

- Bellamy, J. G. (1964). "The Coterel Gang: An Anatomy of a Band of Fourteenth-Century Criminals". The English Historical Review. 79: 698–717. OCLC 754650998.

- Blomefield, F. (1805). "Hundred of Diss: Osmundeston, or Scolce". An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk. I. London: W. Miller. pp. 130 136. OCLC 59116555.

- Britnell, R. H. (1986). Growth and Decline in Colchester, 1300-1525. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52130-572-3.

- Britnell, R. H. (1988). "The Fields and Pastures of Colchester, 1280–1350". Transactions of the Essex Archaeological and History Society. 3rd series. 19. OCLC 863427366.

- Cokayne, G. E. (1926). Gibb, V.; Doubleday, H. A.; White, G. H.; de Walden, H., eds. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: Extant, Extinct, or Dormant. v (14 volumes, 1910–1959, 2nd ed.). London: St Catherine Press. OCLC 163409569.

- Cohn, S. K.; Aiton, D. (2013). Popular Protest in Late Medieval English Towns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10702-780-0.

- C. P. R. (1907). Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, Edward III: 1350-1354. IX (1st ed.). London: H. M. S. O. OCLC 715308987.

- Cromwell, T. (1826). History and Description of the Ancient Town and Borough of Colchester, in Essex. II. London: W. Simpkin & R. Masshall. OCLC 680415281.

- Curry, A. (2003). The Hundred Years War. British History in Perspective (2nd ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-23062-969-1.

- Furber, E. C. (1953). Essex Sessions of the Peace, 1351, 1377-1379. Colchester: Essex Archaeological Society. OCLC 560727542.

- Goodman, A. (2004). "Vere, Aubrey de, tenth earl of Oxford (1338x40–1400)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28205. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- Google (7 October 2018). "Lexden Park, Colchester" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Hanawalt, B. A. (1975). "Fur-Collar Crime: The Pattern of Crime among the Fourteenth-Century English Nobility". Journal of Social History. 8: 1–17. OCLC 67192747.

- Harris, G. (2017). "Organised Crime in Fourteenth-Century Essex: Hugh de Badewe, Essex Soldier and Gang Member". In Thornton, C.; Ward, J. Fighting Essex Soldier: Recruitment, War and Society in the Fourteenth Century. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press. pp. 65–77. ISBN 978-1-90929-194-2.

- Hastings, M. (1955). "Review". The American Historical Review. 60: 346–348. OCLC 472353503.

- Hutchinson, W. (1778). A View of Northumberland: With an Excursion to the Abbey of Mailross in Scotland. II. Newcastle: T. Saint. OCLC 644255556.

- Kimball, E. G (1955). "Review". Speculum. 30: 278–280. OCLC 709976972.

- Leese, T. A. (1996). Blood Royal: Issue of the Kings and Queens of Medieval England, 1066-1399 : the Normans and Plantagenets. Bowie, MD: Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-78840-525-9.

- Merriam-Webster (2018). "Thefbote". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Moore, T. (2018). "Walter, Fifth Lord Fitzwalter of Little Dunmow (Essex)". The Soldier in Later Medieval England. Henley Business School, Universities of Reading and Southampton. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- National Archives. "SC 8/311/15549" (c.1348) [manuscript]. Special Collections: Ancient Petitions, Series: SC 8, p. Petitioners: John Fitz Wauter (FitzWalter). Kew: The National Archives.

- National Archives. "JUST 1/266" (1351) [manuscript]. Justices in Eyre, of Assize, of Oyer and Terminer, and of the Peace, etc: Rolls and Files, Series: JUST, p. Essex peace roll. Kew: The National Archives.

- Ormrod, W. M. (2004b). "Bohun, William de, first earl of Northampton (c. 1312–1360)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2778. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- Owst, G. R. (1933). Literature and Pulpit in Medieval England: A Neglected Chapter in the History of English Letters & of the English People (1st ed.). Cambridge: The University Press. OCLC 54217345.

- Phillips, A. (2004). Colchester: A History. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-86077-304-4.

- Powell, W. R. (1991). "Lionel de Bradenham and his Siege of Colchester in 1350". Transactions of the Essex Archaeological and History Society. 3rd series. 22. OCLC 863427366.

- Putnam, B. H. (2013) [1950]. The Place in Legal History of Sir William Shareshull: Chief Justice of the King's Bench 1350-1361 (repr. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10763-450-3.

- Round, J. H. (1913). "Lionel de Bradenham and Colchester". Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society. New. 13: 86–92. OCLC 863427366.

- Sayles, G. O. (1988). The Functions of the Medieval Parliament of England. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-0-90762-892-7.

- Scattergood, V. J. (2004). The Lost Tradition: Essays on Middle English Alliterative Poetry. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-85182-565-3.

- Starr, C. (2004). "Fitzwalter family (per. c. 1200–c. 1500)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54522. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- Starr, C. (2007). Medieval Mercenary: Sir John Hawkwood of Essex. Chelmsford: Essex Record Office. ISBN 978-1-89852-927-9.

- Stow, J. (1908). Kingsford, C. L., ed. A Survey of London: Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Oxford: Oxford. OCLC 906156391.

- Thornton, C.; Ward, J. C. (2017). "Introduction: crown, county and locality". Fighting Essex Soldier: Recruitment, War and Society in the Fourteenth Century. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-1-90929-194-2.

- V. C. H. (1994). A History of the County of Essex. IX: The Borough of Colchester. London: Victoria County History. ISBN 9780197227848.

- Ward, J. C. (1991). Essex Gentry and the County Community in the Fourteenth Century. Chelmsford: Essex Record Office/The Local History Centre, Essex University. ISBN 978-0-90036-086-2.

- Ward, J. C. (1998). "Peasants in Essex c. 1200–c. 1340: The Influence of Landscape and Lordship". Transactions of the Essex Archaeological and History Society. 3rd series. 22. OCLC 863427366.