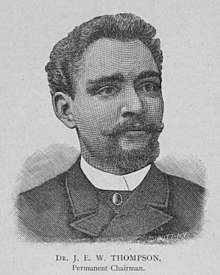

John E. W. Thompson

John Edward West Thompson (December 16, 1860 – October 6, 1918)[1] was an African-American non-career diplomat. He served as U.S. Chargé d'Affaires to Santo Domingo from 1885 to 1889 and as U.S. Minister Resident / Consul General to Haiti from June 30, 1885 to October 17, 1889.

Early Life

Born on December 16, 1860 (possibly 1855), in Brooklyn, New York, John Edward West Thompson lived with his Haitian parents, Edward James and Matilda Frances (White) Thompson. The family moved to Providence, Rhode Island in 1870.

Education

Thompson attended Weston Military Institute and at Lawrence Academy in Groton, Massachusetts. Thompson graduated from Yale School of Medicine in 1883. Shortly after graduation, he studied throughout Europe, Paris, England, Scotland, and Ireland. Thompson became one of the first African-American physicians in New York City in 1884. He received the degree of M.D. from the University of Haiti in 1887. Thompson was also a French scholar and expert in international law.[2]

Diplomacy

President Grover Cleveland appointed Thompson as minister resident to the Republic of Haiti on May 9, 1885.[3] Thompson was also appointed chargé d'affaires to the Republic of San Domingo. His nomination was supported by Noah Porter and Abram Hewitt. Southern Democratic Senators were outraged by Cleveland's nomination of an African-American. Thompson, never-the-less, received a Senate confirmation on January 13 1886 after his arrival in Port-au-Prince. The copy of his credentials were mailed on July 20, 1885. As minister resident, Thompson was called upon, and claimed that he had represented 60,000,000 Americans at San Domingo for six years.[4] One of his first assignments was to investigate the homicide committed by Van Blokklen, imprisoned by the Haitian government, and to report to the Department of State.[5]

On May 26, 1888, disturbances broke out in Haiti over the presidential elections. The two opposing candidates were exiled on June 6. Haitian politicians applied for asylum only five days later. On July 2, military commanders changed. Incendiarism broke out at Port-au-Prince on July 8. The following day, there was a request for a war vessel of the United States. On July 16, there was discontent over the Haitian President Lysius Salomon. Salomon abdicated one month and two days later. Anarchy followed after the abdication. General Seïde Thélémaque led a march at Port-au-Prince on August 25. A provisional government was established by September 5 with the American officers of the U.S.S. Galena. Never-the-less, fighting broke out on October 16, and General Thélémaque died in action. Haitian pirates hijacked an American vessel, the S. S. Haytian Republic. They took it to Port-au-Prince. Thomas F. Bayard and Thompson sent two warships for the release. They arrived to secure the release of the Republic. Thompson was widely praised for the negotiations.[6] The following day, General François Denys Légitime was declared chief of the executive power of Haiti. The French minister was charged with attempted bribery on the next day.

The poor health of owners or representatives of steamship lines led to a series of issues of bills of health. Thompson issued such a bill against Captain Francis Munroe Ramsay and his steamship, USS Boston. The ship was quarantined in the port of Port-au-Prince before she sailed to New York City. On November 15, Thompson certified that the Boston was free of the plague or cholera.[7]

The French minister and the British consul-general both failed to effect a reconciliation of the north to Légitime on November 24. Insurgents declared on December 14 that the ports were closed from commerce by decree of the assembly. Légitime abdicated on August 23, 1889, after an eleven-month rule. General Florvil Hyppolite entered Port-au-Prince only six days after to declare power. Thompson and the Spanish consul-general both intermediated between the opposing political parties.[8]

It was reported that Thompson spent a contingent expense of $333.02 on travel in 1889 and $130.46 in 1890. Meanwhile, Thompson's deduct repayments only amounted to $15.[9]

Later Life

Thompson continued his career as a physician in Mount Hope, New York. He also worked in Atlanta. Thompson became a medical inspector of the Department of Health in 1895. He remained active in politics. In August, 1898, Thompson served as a delegate to the fifth convention of the Negro National Democratic League at the Tammany Hall United Colored Democracy at 152 West 53 Street in New York City. Never-the-less, his presence was not widely regarded. For example, The New York Times carelessly misreported the name of the African-American delegate as "J. E. D. Thompson."[10] In fact, The Times had frequently misspelled his name, once as "J. F. W. Thompson"[11] and "Mr. Thomson" rather than Thompson.[12] Thompson returned to Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1913. His sons, Ernest and Elliott, were in the United States Army during WWI.

Murder

Thomas Saloway, a 30-year-old, had been a patient of Thompson for several months in 1918. He lived at 137 Clinton. Saloway believed to be in poor health, according to friends. It was implied that he was a hypochondriac. Thompson met Saloway on October 2, as discovered by a receipt. The appointment did not go well, as Saloway grew both hostile and crazed.

On October 6, Thompson began to enter his medical office at 966 Main street in Connecticut. Saloway waited for the Thompson to approach, drew a knife and stabbed him in the heart. Nick Scorfacio, an Italian American employee, cleaned Thompson's office before he witnessed the murder. Saloway ran from the scene of the crime.[13] Thompson was rushed to St. Vincent's Hospital, where he died almost instantaneously. Thompson died in the ambulance about twenty minutes after the stabbing. Saloway committed suicide by plunging the same knife into his body.[14]

Saloway premeditated the murder, according to the medical examiner, S. M. Garlic, who performed both autopsies on Thompson and Saloway. The medical examiner based his claim because the knife wounds were located in the same location of the chests of both men. Meanwhile, Saloway's family did not claim his body to bury.[15]

Thompson's body was held at Louis E. Richard's undertaking parlor on 1476 Main street. His funeral was held on October 11, five days after his death. It was originally reported that he would be buried in St. Michael's the Archangel's Parish.[16] Thompson was buried in Mountain Grove Cemetery in Bridgeport. His wife, Mary C. Thompson, survived him.[17]

Sources

- ↑ Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale College, p. 1606

- ↑ SUMMARY OF THE WEEKLY NEWS (1885). The Nation. New York: The Evening Post Publishing Company.

- ↑ "MINISTER TO HAYTI." The Saint Paul Globe. 9 May. 1885. Retrieved 24 Oct. 2017.

- ↑ Three Catholic Afro-American Congresses. Cincinnati: The American Catholic Tribune. 1893.

- ↑ Alexandria Gazette. 26 May. 1885. Retrieved 22 October. 2017.

- ↑ "Thompson, John Edward West (1855-1918)." Black Past. 2017. Accessed 9 Oct. 2017. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/thompson-john-edward-west-1855-1918.

- ↑ New York Assembly (1889). Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, One Hundred and Twelfth Session, Volume XII.--Nos. 76 to 84 Inclusive. Albany: The Troy Press Company, Printers.

- ↑ U.S. Dept. Of State (1902). General Index to the Published Volumes of the Diplomatic Correspondence and Foreign Relations of the United States, 1861 - 1899. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- ↑ The Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Forty-Second Congress, 1892-1893. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1893.

- ↑ "NEGRO DEMOCRATS MEET." The New York Times. 10 Aug. 1898. Retrieved 29 Oct. 2017.

- ↑ " COLORED DEMOCRATS ORGANIZE. THE REPUBLICAN PARTY NO LONGER THEIR PROTECTOR." The New York Times. 22 Jun. 1892. Retrieved 7 Nov. 2017

- ↑ "COLORED LEAGUE DEMOCRATS. A RESOLUTION TO INDORSE THE FEBRUARY CONVENTION WAS TABLED." The New York Times. 27 May. 1892.

- ↑ "DOCTOR JOHN E. W. THOMPSON, FORMER U.S. MINISTER TO HAITI, FATALLY STABBED BY BRIDGEPORT PATIENT." The New York Age. 12 Oct. 1918. Retrieved 9 Oct. 2017.

- ↑ "Disgruntled Patient Kills Physician and Then Ends Own Life." The Bridgeport Telegram. 7 Oct. 1918. Retrieved 9 Oct. 2017.

- ↑ "Saloway's Body Still Unclaimed." The Bridgeport Telegram. 8 Oct. 1918. Retrieved 9 Oct. 2017.

- ↑ "Dr. John E. W. Thompson." The Bridgeport Telegram. 11 Oct. 1918. Retrieved 9 Oct. 2017

- ↑ "DR. J. E. W.THOMPSON KILLED BY PATIENT." The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 7 Oct. 1918. Accessed 9 Oct. 2017

John E. W. Thompson, U. S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, Office of the Historian, retrieved 2009-07-12

Index to Politicians, The Political Graveyard, retrieved 2009-07-12