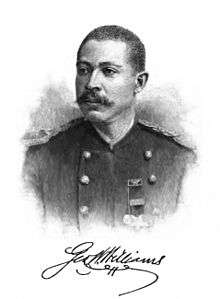

George Washington Williams

| George Washington Williams | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

October 16, 1849 Bedford Springs, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Died |

August 1, 1891 (aged 41) Blackpool, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Soldier, minister, Historian, Lawyer, Journalist |

| Religion | Baptist |

George Washington Williams (October 16, 1849 – August 2, 1891) was an American Civil War soldier, Christian minister, politician, lawyer, journalist, and writer on African-American history.

Shortly before his death he travelled to King Leopold II's Congo Free State. Shocked by what he saw, he wrote an open letter to Leopold in 1890 about the suffering of the region's inhabitants at the hands of Leopold's agents, which spurred the first public outcry against the regime running the Congo since such a regime had caused the loss of millions of lives.[1]

Life and work

Williams was born in 1849 in Bedford Springs, Pennsylvania, to Thomas and Ellen Rouse Williams. The state had abolished slavery after the American Revolution. He was the oldest of four children; his brothers were John, Thomas and Harry Lawsom. He had a limited education and a stint in a "house of refuge" where he learned barbering. Williams enlisted in the Union Army under an assumed name when he was only 14; he fought during the final battles of the American Civil War.

Williams went to Mexico and joined the Republican army under the command of General Espinosa, fighting to overthrow Emperor Maximilian. He received a commission as lieutenant, learned some Spanish, got a reputation as a good gunner, and returned to the U.S. in the spring of 1867.

In the United States, Williams continued his military career, enlisting for a 5-year stint in the army. While serving in the Indian Territory, he was wounded in 1868. He remained hospitalized until his discharge.

Once back in civilian life, the young veteran decided to attend college and was accepted at Howard University, a historically black college in Washington, DC. Records do not show his having stayed there very long. In 1870, he began studies at the Newton Theological Institution near Boston, Massachusetts. In 1874 Williams became the first African American to graduate from Newton.[2]

He met Sarah A. Sterrett during a visit to Chicago in 1873. They were married the following spring and had one son together.

After graduation from Newton Seminary, Williams was ordained as a Baptist minister. He held several pastorates, including the historic Twelfth Baptist Church of Boston.

With support from many of the leaders of his time, such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, Williams founded The Commoner, a weekly journal, in Washington, D.C. (which had no relation to William Jennings Bryan's later publication of the same title). Williams published eight issues.[3]

Williams moved to Cincinnati, Ohio where he studied law under Alphonso Taft (father of President William Howard Taft). He later became the first African American elected to the Ohio State Legislature, serving one term 1880 to 1881.

In 1885, President Chester A. Arthur appointed Williams as "Minister Resident and Consul General" to Haiti. He never served. Grover Cleveland instead appointed John E. W. Thompson to the position.[4]

In 1887, he was given an honorary doctorate at law by Simmons College of Kentucky.[5]

In 1888 he was a delegate to the World's Conference of Foreign Missions at London.[6]

In addition to his religious and political achievements, George W. Williams wrote groundbreaking histories about African Americans in the United States: A History of Negro Troops in the War of Rebellion and The History of the Negro Race in America 1619–1880. The latter was the first overall history of African Americans, showing their participation and contributions from the earliest days of the colonies.

In 1889, Williams was granted an informal audience with King Léopold II of Belgium. At that time, the Congo Free State was the personal possession of the King. He employed a private militia to enforce rubber production by the Congolese and there were widespread rumors of abuses. In spite of the monarch’s objections, Williams went to Central Africa to see the conditions for himself.

From Stanley Falls he addressed "An Open Letter to His Serene Majesty Léopold II, King of the Belgians and Sovereign of the Independent State of Congo" on July 18, 1890.[7] In this letter, he condemned the brutal and inhuman treatment the Congolese were suffering at the hands of Europeans and Africans supervising them for the Congo Free State. He mentioned the role played by Henry M. Stanley, sent to the Congo by the King, in deceiving and mistreating local Congolese. Williams reminded the King that the crimes committed were all committed in his name, making him as guilty as the perpetrators. He appealed to the international community of the day to "call and create an International Commission to investigate the charges herein preferred in the name of Humanity ...".

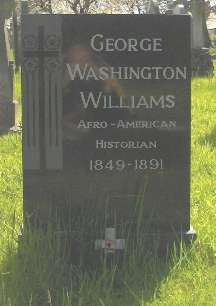

While traveling back from Africa, George Washington Williams died in Blackpool, England, on August 2, 1891, from tuberculosis and pleurisy. He is buried in Layton Cemetery, Blackpool.

Bibliography

- George Washington Williams History of the Negro Race in America From 1619 to 1800 (vol 1) and 1800–1880 (vol 2): Negroes As Slaves, As Soldiers, and As Citizens

- George Washington Williams A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865 (The North's Civil War)

Portrayal in popular culture

Samuel L. Jackson played a fictionalized version of Williams in the 2016 film The Legend of Tarzan.

References

- ↑ Hochschild, Adam, King Leopold's Ghost, Pan Macmillan, London (1998). ISBN 0-330-49233-0. p102

- ↑ Blight, David (2001). Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 169.

- ↑ https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2017225076/

- ↑ Civil Service Reform Association (1885). The Civil Service Record. Boston: Civil Service Reform Association.

- ↑ [No Headline] Washington Bee (Washington, DC) June 4, 1887, page 3, accessed November 8, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7370010/no_headline_washington_bee/

- ↑ Washington, T. Booker, "The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery." New York: Doubleday 1 (1909) p 324-325

- ↑ "An Open Letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold II, King of the Belgians and Sovereign of the Independent State of Congo". 1890.

Further reading

- Franklin, John Hope, George Washington Williams: A Biography, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985; Reprint, Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1998.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Washington Williams. |

- Works by George Washington Williams at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about George Washington Williams at Internet Archive

- George Washington Williams, History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880: Negroes as Slaves, as Soldiers and as Citizens, (1882), at Internet Archive

- George Washington Williams, A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865, (1887), at Internet Archive

- "An Open Letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold II, King of the Belgians and Sovereign of the Independent State of Congo", 1890, at Black Past.

- "Soldier, Scholar, Statesman, Trickster", New York Times, 15 August 1999

- George Washington Williams at Find a Grave

- Video – George Washington Williams: A Portrait of Faith, Courage and Wisdom (run time = 26m29s), hosted by The Ohio Statehouse Capitol Square Review and Advisory Board