James M. Gavin

| James M. Gavin | |

|---|---|

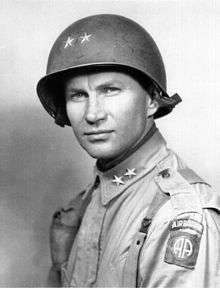

James M. Gavin, pictured here as a major general. | |

| United States Ambassador to France | |

|

In office March 21, 1961 – September 26, 1962 | |

| President | John F. Kennedy |

| Preceded by | Amory Houghton |

| Succeeded by | Charles E. Bohlen |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

James Maurice Gavin March 22, 1907 New York City, New York |

| Died |

February 23, 1990 (aged 82) Baltimore, Maryland |

| Resting place | West Point Cemetery |

| Spouse(s) |

Jean Emert Duncan (1948-1990) Irma Baulsir (1929-? [1] div.) |

| Children | 5 |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) |

The Jumping General Slim Jim Jumpin' Jim |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1924–1958 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Unit | Infantry Branch |

| Commands |

505th Parachute Infantry Regiment 82nd Airborne Division VII Corps |

| Battles/wars | Korean War |

| Awards |

Distinguished Service Cross (2) Distinguished Service Medal Silver Star (2) Bronze Star Medal Purple Heart Distinguished Service Order (United Kingdom) Legion of Honour (France) |

James Maurice "Jumpin' Jim" Gavin (March 22, 1907 – February 23, 1990) was a senior United States Army officer, with the rank of lieutenant general, who was the third Commanding General (CG) of the 82nd Airborne Division during World War II. During the war, he was often referred to as "The Jumping General" because of his practice of taking part in combat jumps with the paratroopers under his command; he was the only American general officer to make four combat jumps in the war.

Gavin was the youngest major general to command an American division in World War II, being only 37 upon promotion,[2] and the youngest lieutenant general after the war, in March 1955. He was awarded two Distinguished Service Crosses and several other decorations for his service in the war. During combat, he was known for his habit of carrying an M1 Garand rifle typically carried by enlisted U.S. infantry soldiers, as opposed to the M1 carbine rifles traditionally carried by officers.[3]

Gavin also worked against segregation in the U.S. Army,[3] which gained him some notoriety.

Early life

Gavin was born in Brooklyn, New York on March 22, 1907. His precise ancestry is unclear. His mother may have been an Irish immigrant, Katherine Ryan, and his father James Nally (also of Irish heritage), although official documentation lists Thomas Ryan as father; possibly in order to make the birth legitimate. The birth certificate lists his name as James Nally Ryan, although Nally was crossed out. When he was about two years old, he was placed in the Convent of Mercy orphanage in Brooklyn, where he remained until he was adopted in 1909 by Martin and Mary Gavin from Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania and given the name James Maurice Gavin.

Gavin took his first job as a newspaper delivery boy at the age of 10. By the age of 11, he had two routes and was an agent for three out-of-town papers. During this time, he enjoyed following articles about World War I. In the eighth grade, he moved on from the paper job and started working at a barbershop. There he listened to the stories of the old miners. This led him to realize he did not want to be a miner. In school, he learned about the Civil War. From that point on, he decided to study everything he could about the subject. He was amazed at what he discovered and decided if he wanted to learn this "magic" of controlling thousands of troops, from miles away, he would have to continue his education at the United States Military Academy at West Point.[4]

His adoptive father was a hard-working coal miner, but the family still had trouble making ends meet. Gavin quit school after eighth grade and became a full-time clerk at a shoe store for $12.50 a week. His next stint was as a manager for Jewel Oil Company.[5] A combination of restlessness and limited future opportunities in his hometown caused Gavin to run away from home. In March 1924, on his 17th birthday, he took the night train to New York. The first thing he did upon arriving was to send a telegram to his parents saying everything was all right to prevent them from reporting him missing to the police. After that, he started looking for a job.

Military career

Enlistment and West Point

At the end of March 1924, aged 17, Gavin spoke to a U.S. Army recruiting officer. Since he was under 18, he needed parental consent to enlist. Knowing that his adoptive parents would not consent, Gavin told the recruiter he was an orphan. The recruiting officer took him and a couple of other underage boys, who were orphans, to a lawyer who declared himself their guardian and signed the parental consent paperwork. On April 1, 1924, Gavin was sworn into the U.S. Army, and was stationed in Panama. His basic training was performed on the job in his unit, the U.S. Coast Artillery at Fort Sherman. He served as a crewmember of a 155 mm gun, under the command of Sergeant McCarthy, who described him as fine. Another person he looked up to was his first sergeant, an American Indian named "Chief" Williams.

Gavin spent his spare time reading books from the library, notably Great Captains and a biography of Hannibal. He had been forced to quit school in seventh grade in order to help support his family, and acutely felt his lack of education. In addition, he made excursions in the region, trying to satisfy his boundless curiosity about everything. First Sergeant Williams recognized Gavin's potential and made him his assistant; Gavin was promoted to corporal six months later.

He wished to advance in the army, and on Williams's advice, applied to a local army school, from which the best graduates got the chance to attend West Point. Gavin passed the physical examinations and was assigned with a dozen other men to a school in Corozal, which was a small army depot in the Canal Zone. He started school on September 1, 1924. In order to prepare for the entrance exams into West Point, Gavin was tutored by another mentor, Lieutenant Percy Black, from 8 o'clock in the morning until noon on algebra, geometry, English and history. He passed the exams and was allowed to apply to West Point.

Gavin arrived at West Point in the summer of 1925. On the application forms, he indicated his age as 21 (instead of 18) to hide the fact that he was not old enough to join the army when he did. Since Gavin missed the basic education which was needed to understand the lessons, he rose at 4:30 every morning and read his books in the bathroom, the only place with enough light to read. After four years of hard work, he graduated in June 1929. In the 1929 edition of the West Point yearbook, Howitzer, he was mentioned as a boxer and as the cadet who had already been a soldier. After his graduation and his commissioning as a second lieutenant, he married Irma Baulsir on September 5, 1929.

Various postings

Gavin was posted to Camp Harry J. Jones near Douglas, Arizona on the U.S.-Mexican border. This camp housed the 25th Infantry Regiment (one of the entirely African-American Buffalo Soldier regiments). He stayed in this posting for three years.

Afterwards, Gavin attended the United States Army Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia. This school was managed by Colonel George C. Marshall, who had brought Joseph Stillwell with him to lead the Tactics department. Marshall and Stillwell taught their students not to rely on lengthy written orders, but rather to give rough guidelines for the commanders in the field to execute as they saw fit, and to let the field commanders do the actual tactical thinking; this was contrary to all other education in the US Army thus far. Gavin himself had this to say about Stilwell and his methods: "He was a superb officer in that position, hard and tough worker, and he demanded much, always insisting that anything you ask the troops to do, you must be able to do yourself."

The time spent at Fort Benning was a happy time for Gavin, but his marriage with Irma Baulsir was not going well. She had moved with him to Fort Benning, and lived in a town nearby. On December 23, 1932 they drove to Baulsir's parents in Washington, D.C. to celebrate Christmas together. Irma decided she was happier there, and remained with her parents. In February 1933, Irma became pregnant. Their daughter, Gavin's first child, Barbara, was born while Gavin was away from Fort Sill on a hunting trip. "She was very unhappy with me, as was her mother", Gavin later wrote. Irma remained in Washington during most of their marriage, which ended in divorce upon his return from the war.

In 1933, Gavin, who had no desire to become an instructor for new recruits, was posted to the 28th and 29th Infantry Regiment at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, under the command of General Lesley J. McNair. He spent most of his free time in, as he called it, the "excellent library" of this fort, while the other soldiers spent most of their time partying, shooting, and playing polo. One author in particular impressed Gavin: J.F.C. Fuller. Gavin said about him: "[He] saw clearly the implications of machines, weapons, gasoline, oil, tanks and airplanes. I read with avidity all of his writings."

In 1936, Gavin was posted to the Philippines. While there, he became very concerned about the US ability to counter possible Japanese plans for expansion. The 20,000 soldiers stationed there were badly equipped. In the book Paratrooper: The Life of Gen. James M. Gavin, he is quoted as saying, "Our weapons and equipment were no better than those used in World War I". After 1½ years in the Philippines, he returned to Washington with his family and served with the 3rd Infantry Division in the Vancouver Barracks. Gavin was promoted to captain and held his first command position as commanding officer of K Company of the 7th Infantry Regiment.

While stationed at Fort Ord, California, he received an injury to his right eye during a sports match. Gavin feared that this would end his military career, and he visited a physician in Monterey, California. The physician diagnosed a retinal detachment, and recommended an eye patch for 90 days. Gavin decided to rely on his eye healing by itself to hide the injury.

West Point again

Gavin was ordered back to West Point, to work in the Tactics Faculty there. He was overjoyed by this posting, as he could further develop his skills there. With the German Blitzkrieg steamrolling over Europe, the Tactics Faculty was requested to analyze and understand the German tactics, vehicles, and armaments. His superior at West Point called him "a natural instructor", and his students declared that he was the best teacher they had.

Gavin was very concerned about the fact that US Army vehicles, weapons, and ammunition were at best a copy of the German equipment. "It would not be sufficient to copy the Germans," he declared. For the first time, Gavin talked about using airborne forces: "From what we had seen so far, it was clear the most promising area of all was airborne warfare, bringing the parachute troops and the glider troops to the battlefield in masses, especially trained, armed, and equipped for that kind of warfare."

He took an interest in the German airborne assault on the Fort Eben-Emael in Belgium in May 1940, in which well-equipped German paratroopers dropped from the sky at night and captured the fort. This event and his extensive study on Stonewall Jackson's movement tactics led him to volunteer for a posting in the new airborne unit in April 1941.

World War II

Constructing an airborne army

Gavin began training at the new Parachute School in Fort Benning in August 1941.[6] After graduating in August, he served in an experimental unit. His first command was as a captain and the commanding officer of C Company of the newly established 503rd Parachute Infantry Battalion.

Gavin's friends William T. Ryder, commander of airborne training, and William P. Yarborough, communications officer of the Provisional Airborne Group, convinced Colonel William C. Lee to let Gavin develop the tactics and basic rules of airborne combat. Lee followed up on this recommendation, and made Gavin his operations and training officer (S-3). On October 16, 1941, Gavin was promoted to major.

One of Gavin's first priorities was determining how airborne troops could be used most effectively. His first action was writing FM 31-30: Tactics and Technique of Air-Borne Troops. He used information about Soviet and German experiences with paratroopers and glider troops, and also used his own experience in tactics and warfare. The manual contained information about tactics, but also about the organization of the paratroopers, what kind of operations they could execute, and what they would need to execute their task effectively. Later, when Gavin was asked what made his career take off so fast, he would answer, "I wrote the book".

In February 1942, shortly after the United States entered World War II, Gavin took a condensed course at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, which qualified him to serve on the staff of a division. He returned to the Provisional Airborne Group and was tasked with building up an airborne division. In the spring of 1942, Gavin and Lee went to Army Headquarters in Washington, D.C., to discuss the order of battle for the first U.S. airborne division. The 82nd Infantry Division, then stationed in Camp Claiborne, Louisiana and commanded by Major General Omar Bradley, was selected to be converted into the first American airborne division and subsequently became the 82nd Airborne Division. Command of the 82nd went to Major General Matthew Ridgway. Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair's influence led to the division's initial composition of two glider infantry regiments and one parachute infantry regiment, with organic parachute and glider artillery and other support units.

In August 1942, Gavin became the commanding officer of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (505th PIR) at Fort Benning which had been activated shortly before on July 6.[7] He was, aged just 35, promoted to colonel shortly thereafter. Gavin built this regiment from the ground up. He led his troops on long marches and realistic training sessions, creating the training missions himself and leading the marches personally. He also placed great value on having his officers "the first out of the airplane door and the last in the chow line". This practice has continued to and with present-day U.S. airborne units. After months of training, Gavin had the regiment tested one last time:

As we neared our time to leave, on the way to war, I had an exercise that required them to leave our barracks area at 7:00 P.M. and march all night to an area near the town of Cottonwood, Alabama, a march about 23 miles. There we maneuvered all day and in effect we seized and held an airhead. We broke up the exercise about 8:00 P.M. and started the troopers back by another route through dense pine forest, by way of backwoods roads. About 11:00 P.M., we went into bivouac. After about one hour's sleep, the troopers were awakened to resume the march. [...] In 36 hours the regiment had marched well over 50 miles, maneuvered and seized an airhead and defended it from counterattack while carrying full combat loads and living off reserve rations.

Preparations for combat

In February 1943, the 82nd Airborne Division, consisting of the 325th and 326th Glider Infantry Regiments and the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, was selected to participate in the Allied invasion of Sicily, codenamed Operation Husky. Not enough gliders were available to have both glider regiments take part in the landings, so the 326th Glider Infantry Regiment was relieved from assignment to the 82nd and replaced by Gavin's 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, which arrived at Fort Bragg on February 12.[7]

Gavin arranged a last regimental-sized jump for training and demonstration purposes before the division was shipped to North Africa. On April 10, 1943, Ridgway explained what their next mission would be: Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily. Gavin's regiment would be the first ever in the history of the United States Army to make a regimental-sized airborne landing. He declared, "It is exciting and stimulating that the first regimental parachute operation in the history of our army is to be taken by the 505th." On April 29, 1943, Gavin left the harbor of New York on board the SS Monterey, arriving in Casablanca on May 10, 1943. Lieutenant General George Patton, the U.S. Seventh Army commander, suggested performing the invasion at night, but Ridgway and Gavin disagreed because they had not practiced night jumps. After mounting casualties during practice jumps, Gavin canceled all practice jumps until the invasion.

The regiment was transported to Kairouan in Tunisia, and on July 9 at 10:00am, they entered the planes that would take them to Sicily. Their mission was to land 24 hours before the planned day/time of major combat initiation ("D-Day") to the north and east of Gela and take and hold the surrounding area to split the German line of supply and disrupt their communications.

Operation Husky

A soldier informed Gavin that the windspeed at the landing site was 56 km/h (about 34 miles per hour). During the planning phase, 24 km/h (about 14.5 miles per hour) had been assumed. After one hour of flying, the plane crew could see the bombardment of the invasion beaches. Gavin ordered his men to prepare for the jump, and a few minutes later was the first paratrooper to jump from the plane. Due to the higher-than-expected windspeed, he sprained his ankle while landing. After assembling a group of 20 men, his S-3, Major Benjamin H. Vandervoort, and his S-1, Captain Ireland, he realized that they had drifted off course and were miles from the intended landing areas. He could see signs of combat twenty miles onwards; he gathered his men and headed towards the combat zone.

With a small band of between eight and twenty paratroopers of the 505th, Gavin began to march toward the sound of the guns. "He had no idea where his regiment was and only a vague idea as to exactly where he was. We walked all night," said Major Vandervoort. The paratroopers did not pose a real threat as a fighting force, but their guerilla tactics were nevertheless very effective. They aggressively took on enemy forces, leaving the impression of a much larger force. At one point on the morning of July 10, Gavin's tiny band encountered a 35-man Italian anti-paratroop patrol. An intense firefight ensued, and the Italians were driven back. Several paratroopers were wounded before Gavin and his men were able to gradually disengage. Gavin was the last man to withdraw. "We were sweaty, tired and distressed at having to leave [our] wounded behind," said Vandervoort. "The colonel looked over his paltry six-man command and said, 'This is a hell of a place for a regimental commander to be.'"

At about 8:30 a.m. on July 11, as Gavin was headed west along Route 115 in the direction of Gela, he began rounding up scattered groups of 505th paratroopers and infantrymen of the 45th Division and successfully attacked a ridge that overlooked a road junction at the east end of the Acate Valley. It was called Biazza Ridge. Gavin established hasty defenses on the ridge, overlooking the road junction, Ponte Dirillo and the Acate River valley. Although he had no tanks or artillery to support him, he immediately appreciated the importance of holding the ridge as the only Allied force between the Germans and their unhindered exploitation of the exposed left flank of the 45th Division and the thinly held right flank of the 1st Division. Against Gavin that day was the entire eastern task force of the Hermann Göring Division: at least 700 infantry, an armored artillery battalion, and a company of Tiger tanks.

The German objective was nothing less than counterattacking and throwing the 1st and 45th Divisions back into the sea. Although the attacks of July 10 had failed, those launched the next day posed a dire threat to the still tenuous 45th Division beachhead. For some inexplicable reason, the Germans failed to act aggressively against Gavin's outgunned and outmatched force. Even so, that afternoon, a panzer force attacked Biazza Ridge. Gavin made clear to his men, "We're staying on this goddamned ridge – no matter what happens."

The defenders of Biazza Ridge managed to capture two 75-mm pack howitzers, which they turned into direct fire weapons to defend the ridge. One managed to knock out one of the attacking Tiger tanks. By early evening, the situation had turned grim when six American M4 Sherman tanks suddenly appeared, eliciting cheers from the weary paratroopers, who had been joined by others, including some airborne engineers, infantry, clerks, cooks and truck drivers. With this scratch force and the Shermans, Gavin counterattacked and in so doing deterred the Germans from pressing their considerable advantage. The battle ended with the Americans still in control of Biazza Ridge. For his feats of valor that day, Colonel Gavin was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

On December 9, 1943, Gavin was promoted to brigadier general and became the assistant division commander of the 82nd Airborne Division.[7] Being only 36 years old at the time, he was one of the youngest Army officers to become a general in World War II. The 82nd Airborne moved to England during the early months of 1944.

D-Day and Mission Boston

Gavin was part of Mission Boston on D-Day. This was a parachute combat assault conducted at night by the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division on June 6, 1944, as part of the American airborne landings in Normandy. The intended objective was to secure an area of roughly 10 square miles (26 km2) on either side of the Merderet River. They were to capture the town of Sainte-Mère-Église, a crucial communications crossroad behind Utah Beach, and to block the approaches into the area from the west and southwest. They were to seize causeways and bridges over the Merderet at La Fière and Chef-du-Pont, destroy the highway bridge over the Douve River at Pont l'Abbé (now Étienville), and secure the area west of Sainte-Mère-Église to establish a defensive line between Gourbesville and Renouf. Gavin was to describe the operation as having two interrelated challenges – it had to be 'planned and staged with one eye on deception and one on the assault'.[8]

To complete its assignments, the 82nd Airborne Division was divided into three forces. Gavin commanded Force A (parachute): the three parachute infantry regiments and support detachments. The drops were scattered by bad weather and German antiaircraft fire over an area three to four times larger than planned; ironically, this gave the Germans the impression of a much larger force. Two regiments of the division were given the mission of blocking approaches west of the Merderet River, but most of their troops missed their drop zones entirely. The 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment jumped accurately and captured its objective, the town of Sainte-Mère-Église, which proved essential to the success of the division.

The 1st Battalion captured bridges over the Merderet at Manoir de la Fière and Chef-du-Pont. Gavin returned from Chef-du-Pont and withdrew all but a platoon to beef up the defense at Manoir de la Fière. About 2.2 miles west of Sainte-Mère-Église and 175 yards east of La Fière Bridge, on Route D15, a historical marker indicates the supposed location of Gavin's foxhole.[9]

Operation Market Garden

Gavin assumed command of the 82nd Airborne Division on August 8, 1944, and was promoted to major general in October.[10] For the first time, Gavin would lead the 82nd Airborne into combat. On Sunday, September 17, Operation Market Garden took off. Market Garden, devised by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, consisted of an airborne attack of three British and American airborne divisions. The 82nd was to take the bridge across the Maas river in Grave, seize at least one of four bridges across the Maas-Waal canal, and the bridge across the Waal river in Nijmegen. The 82nd was also to take control of the high grounds in the vicinity of Groesbeek, a small Dutch town near the German border. The ultimate objective of the offensive was Arnhem.

In the drop into the Netherlands, Gavin landed on hard pavement instead of grass, injuring his back. He had it inspected by a doctor a few days later, who claimed that his back was fine, and so Gavin continued normally throughout the entirety of the war. Five years later, he had his back examined at Walter Reed Hospital, where he learned that he had, in fact, fractured two discs in the jump.[11]

Gavin failed to prioritise the capture of the bridge over the Rhine and instead chose to concentrate his troops initially further south on the Groesbeek Heights. This failure led to the vital bridge being heavily reinforced and in German hands for a further four days and seriously delaying XXX Corp relief of 1st Airborne Div at Arnhem. The 504th took the bridge across the Wale river, but it was too late as the British paras of the 2nd Parachute Battalion, 1st Parachute Brigade of the British 1st Airborne Division, could not hold on any longer to their north side of the Arnhem bridge and were defeated. The 82nd would stay in the Netherlands until November 13, when it was transferred to their new billets in Sisonne et Suippes, France.

Battle of the Bulge and End of the War in Europe

Gavin also led the 82nd during its fighting in the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 and January 1945.[12] The division was in SHAEF reserve in France at the start of the battle, and deployed as part of the Allied reaction to the German offensive. It operated in the northern sector of the battle, defending the towns of La Gleize and Stoumont against attacks by Kampfgruppe Peiper and elements of three Waffen-SS Panzer divisions. After the German offensive stalled, Gavin led the 82nd during the Allied counterattack in January 1945 that erased the German penetration.

After helping to secure the Ruhr, the 82nd Airborne Division ended the war at Ludwigslust past the Elbe River, accepting the surrender of over 150,000 men of Lieutenant General Kurt von Tippelskirch's 21st Army. General Omar Bradley, commanding the U.S. 12th Army Group, stated in a 1975 interview with Gavin that Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery, commanding the Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group, had told him that German opposition was too great to cross the Elbe. When Gavin's 82nd crossed the river, in company with the British 6th Airborne Division, the 82nd Airborne Division moved 36 miles in one day and captured over 100,000 troops, causing great laughter in Bradley's 12th Army Group headquarters.[13]

Following Germany's surrender, the 82nd Airborne Division entered Berlin for occupation duty, lasting from April until December 1945. In Berlin General George S. Patton was so impressed with the 82nd's honor guard he said, "In all my years in the Army and all the honor guards I have ever seen, the 82nd's honor guard is undoubtedly the best." Hence the "All-American" became also known as "America's Guard of Honor".[14] The war ended before their scheduled participation in the Allied invasion of Japan, Operation Downfall.

Post-world war

Gavin also played a central role in integrating the U.S. military, beginning with his incorporation of the all-black 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion into the 82nd Airborne Division. The 555th's commander, Colonel Bradley Biggs, referred to Gavin as perhaps the most "color-blind" Army officer in the entire service. Biggs' unit distinguished itself as "smokejumpers" in 1945, combating forest fires and disarming Japanese balloon bombs.

After the war, Gavin went on to high postwar command. He was a key player in stimulating the discussions which led to the Pentomic Division. As Army Chief of Research and Development and public author, he called for the use of mechanized troops transported by air to become a modern form of cavalry.[15][16] He proposed deploying troops and light armored fighting vehicles by glider (or specially designed air dropped pod), aircraft, or helicopter to perform reconnaissance, raids, and screening operations. This led to the Howze Board, which had a great influence on the Army's use of helicopters—first seen during the Vietnam War.[17][18]

While the U.S. Army's Chief of Research & Development, he established a requirement for an armored, tracked, air-droppable Universal Carrier. This requirement crystallized in 1956 as the AAM/PVF (Airborne Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle). The result was fielded in 1960 as the M113.

Gavin retired from the U.S. Army in March 1958 as a lieutenant general. He wrote a book, War and Peace in the Space Age,[19] published in mid-1958, which, among other things, detailed his reasons for leaving the army at that time.

Later years and death

Upon retiring from the U.S. Army, Gavin was recruited by an industrial research and consulting firm, Arthur D. Little, Inc. He began as a vice president in 1958, became president of the company in 1960 and eventually served as both president and chairman of the board until his retirement in 1977. During his tenure at ADL, he grew a $10 million domestic company into a $70 million international company. Gavin remained as a consultant with ADL after his retirement. He served on the boards of several Boston organizations, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Northeastern University, and some business boards as well.

In 1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy asked Gavin to take a leave of absence from ADL and answer his country's call once again, to serve as U.S. Ambassador to France. Kennedy hoped Gavin would be able to improve deteriorating diplomatic relations with France, due to his experiences with the French during World War II, and his wartime relationship with France's President, General Charles De Gaulle. This proved to be a successful strategy and Gavin served as Ambassador to France in 1961 and 1962. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter considered the 70-year-old Gavin for Director of the CIA before settling on Admiral Stansfield Turner.[20]

Along with David Shoup and Matthew Ridgway, Gavin became one of the more visible former military critics of the Vietnam War.

General Gavin was portrayed by Robert Ryan[21] in The Longest Day, and by Ryan O'Neal in A Bridge Too Far. Gavin served as an advisor on both films.[22]

James Gavin died on February 23, 1990 and is buried to the immediate east of the Old Chapel at the United States Military Academy Post Cemetery at West Point. He was survived by his widow, Jean, his five daughters, ten grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.[23]

Private life

Gavin and his wife Irma divorced after World War II. He married Jean Emert Duncan of Knoxville, Tennessee, in July 1948 and remained married to her until his death in 1990. He adopted Jean's daughter, Caroline Ann, by her first marriage. He and Jean had three daughters, Patricia Catherine, Marjorie Aileen, and Chloe Jean. He also had a daughter named Barbara with his first wife. Barbara saved the letters her father sent to her during the war, and used them to author a 2007 book, The General and His Daughter: The War Time Letters of General James Gavin to his Daughter Barbara.[24] Gavin had a reputation as a womanizer.[25] Among his wartime lovers were the film star Marlene Dietrich[26] and journalist Martha Gellhorn.[27]

Military awards

Gavin's military decorations and awards include:[28]

- Badges

|

|

|

- Decorations

| Distinguished Service Cross with bronze oak leaf cluster | |

| Army Distinguished Service Medal | |

| Silver Star with bronze oak leaf cluster | |

| Bronze Star | |

| Purple Heart | |

| Army Commendation Medal |

- Unit Award

| Army Presidential Unit Citation |

- Service Medals

- Foreign Awards

| British Distinguished Service Order | |

| Legion of Honour (Grand Officer) | |

| French Croix de guerre with Palm | |

| Belgian Croix de guerre with Palm | |

| Netherlands Order of Orange-Nassau (Grand Officer) with swords |

Dates of rank

| Insignia | Rank | Component | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| No insignia | Enlisted | Coast Artillery Corps | April 7, 1924 |

| No insignia | Cadet | United States Military Academy | July 1, 1925 |

| Second Lieutenant | Regular Army | June 13, 1929 | |

| First Lieutenant | Regular Army | November 1, 1934 | |

| Captain | Regular Army | June 13, 1939 | |

| Major | Army of the United States | October 10, 1941 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | Army of the United States | February 1, 1942 | |

| Colonel | Army of the United States | September 25, 1942 | |

| Brigadier General | Army of the United States | September 23, 1943 | |

| Major General | Army of the United States | October 20, 1944 | |

| Major | Regular Army | June 13, 1946 | |

| Colonel | Regular Army | June 10, 1948 | |

| Brigadier General | Regular Army | May 2, 1953 | |

| Major General | Regular Army | July 13, 1954 | |

| Lieutenant General | Army of the United States | March 24, 1955 | |

| Lieutenant General | Retired List | March 31, 1958 |

Books

General Gavin authored five books:

- Airborne Warfare (1947) is a recap of the development and future of aircraft delivered forces.

- War and Peace in the Space Age (1958) details why he left the army, the perilously inadequate state of U.S. military, scientific and technological development at that time, the reasons for it, and precise goals the U.S. needed to achieve for her national defense.

- Crisis Now (with Arthur Hadley) (1968) offered specific solutions to end the Vietnam War, and as important, observations on America's domestic crises and creative, innovative solutions for them.

- On to Berlin: Battles of an Airborne Commander 1943–1946 (1976), is an account of his experiences commanding the 82nd Airborne Division. He also co-authored

- France and the Civil War in America (1962) with André Maurois.

Memorials

The street that leads to the Waal Bridge in Nijmegen is now called General James Gavin Street.[30] Near to the location of his para drop during Operation Market-Garden in Groesbeek a residential area is named in his honour.[31]

A street in Thorpe Astley, a suburb of Leicester, England, was named Gavin Close in his honour. Thorpe Astley forms part of Braunstone Town in which General Gavin was stationed at Braunstone Hall, prior to the D-Day landings.[32]

There is also a small memorial in his native Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania, where he grew up, commemorating his service. There are also two memorials in Osterville, Massachusetts, where he and his family spent summers for many years. In 1975, American Electric Power completed the 2,600-megawatt General James M. Gavin Power Plant on the Ohio River, near Cheshire, Ohio. The plant boasts dual stacks of 830 feet and dual cooling towers of 430 feet. It is the largest coal-fired power facility in Ohio, and one of the largest in the nation.

In 1986, the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment created the "Gavin Squad Competition". This competition was designed to identify the most proficient rifle squad in the regiment. The original competition was won by a squad from 1st Platoon, Bravo Company, 3/505th PIR. Gavin was on hand to award the nine man squad their trophy. The competition is still held every year if the wartime deployment schedule allows it.

Recommended reading

- Atkinson, Rick. The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943–1944. New York: Henry Holt, 2007.

- Booth, T. Michael, and Duncan Spencer. Paratrooper: The Life of General James M. Gavin. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994.

- Fauntleroy, Barbara Gavin. The General and His Daughter: The Wartime Letters of General James M. Gavin to His Daughter Barbara. New York: Fordham University Press, 2007.

- Gavin, James M. The James M. Gavin Papers. U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, PA.

- Hein, David. http://ausar-web01.inetu.net/publications/armymagazine/archive/2013/07/Documents/Hein_July2013.pdf "Counterpoint to Combat: The Education of Airborne Commander James M. Gavin" ARMY 63, no. 7 (July 2013: 49–52.]

- LoFaro, Guy. The Sword of St. Michael: The 82nd Airborne Division in World War II. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo, 2011.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Gavin and Irma Baulsir divorced sometime between the end of the war in 1945 and 1948 when he married Jean Duncan"

- ↑ Fauntleroy, Barbara Gavin (2007). The General and His Daughter: The Wartime Letters of General James M. Gavin to His Daughter Barbara. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- 1 2 Carlo D'Este (June 2, 2011). "Jim Gavin: The General Who Jumped First". historynet.com.

- ↑ Gavin, War And Peace In The Space Age, 1958, pp. 22–27

- ↑ Gavin, War And Peace In The Space Age, 1958, pp. 28–29

- ↑ http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-2E2

- 1 2 3 http://www.ww2-airborne.us/units/505/505.html

- ↑ Gavin, James. Airborne Warfare, 1947, p37.

- ↑ Historical marker. General Gavin's foxhole.

- ↑ http://en.ww2awards.com/person/34390

- ↑ Ambrose pg. 121

- ↑ Bouwmeester, Maj. Han (2004), Beginning of the End: The Leadership of SS Obersturmbannführer Jochen Peiper

- ↑ Ellis, John (1990). Brute force: allied strategy and tactics in the Second World War. Deutsch. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-233-97958-8. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ Reynolds, David (1 September 1998). Paras: An Illustrated History of Britain's Airborne Forces. Sutton. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-7509-1723-0. Retrieved 12 September 2012

- ↑ Gavin, James. Airborne Warfare (1947)

- ↑ Gavin, James. "Cavalry and I Don't Mean Horses." Harper's In about 1953 Lt General Gavin served as Commander of the U.S. 7th Army based in Germany. Sgt A Corrao; Served as driver for Gen Gavin in 29th Car Co Kelly Barracks Germany VII Corps HQ.8/54-9/55 (April 1954): 54–60.

- ↑ Krepinevich, Andrew. The Army and Vietnam, 1986. pp. 118–127

- ↑ Marhnken, Thomas. Technology and the American Way of War since 1945, 2008. pp. 100–103.

- ↑ James Maurice, Gavin. War And Peace In The Space Age (hardcover) (1958 ed.). Harper. ASIN B000OKLL8G. Retrieved April 3, 2015 – via books.google.com.au.

- ↑

- ↑ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0056197/fullcredits?ref_=tt_ov_st_sm/ref>

- ↑ "James M. Gavin at the Internet Movie Database". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ↑ New York Times Obituary, "Lieut. Gen. James Gavin, 82, Dies; Champion and Critic of Military" by Glenn Fowler, 25 February 1990

- ↑ "The General and His Daughter: The Wartime Letters of General James M. Gavin to His Daughter Barbara". Gavin505.com. Ridgefield, CT: Barbara Gavin Fauntleroy. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Blair, Clay (May 22, 1994). "Jumping into History (book review of Paratrooper: The Life of Gen. James M. Gavin by T. Michael Booth and Duncan Spencer)". Washington Post.

- ↑ Ryan, David Stuart (2013). The Blue Angel - The Life and Films of Marlene Dietrich. Charleston, NC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-4564-6578-0.

- ↑ Moorehead, Caroline (2003). Martha Gellhorn: A Life. New York, NY: Random House. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-09-928401-7.

- ↑ Houterman, Hans. "US Army Officers 1939–1945: Gavin, James Maurice". unithistories. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ↑ Official Register of Commissioned Officers of the United States Army, 1948. pg. 644.

- ↑ Nijmegen memorials, stephen-stratford.com; accessed July 16, 2015.

- ↑ Google maps

- ↑ Braunstone Town Council minutes, braunstonetown.leicestershireparishcouncils.org; accessed July 16, 2015.

References

- Ambrose, Stephen (1997). Citizen Soldiers. Touchstone. ISBN 0-684-84801-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James M. Gavin. |

- James M. Gavin on IMDb

- "Military Security Blanket" Audio interview at Center for Study of Democratic Institutions

- James M. Gavin Collection US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, Pennsylvania

- James M. Gavin (1907–1990) at Find a Grave

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Matthew Ridgway |

Commanding General 82nd Airborne Division 1944–1948 |

Succeeded by Clovis E. Byers |

| Preceded by Withers A. Burress |

Commanding General VII Corps 1952–1954 |

Succeeded by Henry I. Hodes |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Amory Houghton |

United States Ambassador to France 1961–1962 |

Succeeded by Charles E. Bohlen |