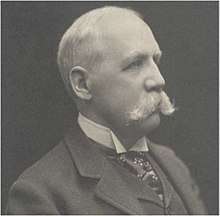

James Hood Wright

James Hood Wright (known professionally as J. Hood Wright; November 4, 1836 – November 12, 1894) was an American banker, financier, corporate director, business magnate, and railroad man of the nineteenth century. He was associated with J. P. Morgan and Thomas Edison. He became wealthy and was involved with philanthropy.

Early life

Wright was born in the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on November 2, 1836.[1] His parents were William Wright and Sarah (Hood) Wright.[1] He received his schooling at the Philadelphia public schools.[1] Wright took his first job as a dry-goods clerk when he was still a teenager. He worked at this for several years.[2]

Mid life and career

Wright's next job in his early 20s was as a clerk at the Philadelphia banking firm of Drexel & Company. He had a finance bookkeeping ability and was promoted to positions of higher responsibility in the company within a few years. Wright became one of the partners in the company around 1864. In 1871 the firm became Drexel, Morgan & Company. He was one of the partners of this new firm.[3] He had a natural ability to detect counterfeit money and was given positions of looking over suspicious counterfeit money.[4] Wright then moved to New York City permanently to work with the firm.[1]

Wright took an interest in the securities of corporations and was a board member in The Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad; the Southern Railway; the Long Island Rail Road; the Edison Electric Illuminating Company; and the New York Guaranty and Indemnity Company.[4] He worked with Thomas Edison at Menlo Park and helped financially in developing the light bulb.[5]

Personal life

Wright married Mary Robinson, widow of John M. Robinson, partner of Drexel, Morgan & Co., at the Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia on March 1, 1881.[6] The flowers at the wedding consisted of azaleas, acacias, callas, tulips, and hyacinths.[7] A novelty of the wedding was that all that attended could take home with them whatever flowers they wanted.[8] The newly wedded couple went to Washington D.C. for their honeymoon in a railroad car that was provided for them.[3][9]

An electric lighting system was installed at Wright's residence in New York City, where the electric generator was located and the Edison lamps were set up with the first permanent fixtures for electric lighting.[10] This was the first private residence to be illuminated by Edison incandescent lamps,[11][12][13] and also the first to be powered by a generator on the premises that provided the electricity for the Edison lamps.[14][15] In England at William Armstrong's Cragside house a set of Joseph Swan's incandescent lamps was installed in December 1880.[16][17] J. P. Morgan, the banker, had visited Edison in January 1881 on the idea to see if his electric lights could be used for illumination of a house. Edison assured him it could. The banker told Edison that when he moved to his new house he would buy one of his electric lighting systems that included a generator for the electricity. Wright, however, installed Edison incandescent lamps and an electric power generating system by December to illuminate his residence before Morgan had his new home finished.[14] It was not until autumn of 1882 before Morgan wired his home for electric lighting.[18]

Associations and social clubs

Wright was president of the Manhattan Hospital and associated with New York museums.[4] He became affiliated with the New York Riding Club and the city Yacht Club.[3] Wright was a giver to philanthropic institutions including the Knickerbocker Hospital,[19] and the Washington Heights Library that became the New York Public Library.[1] He was associated with the Republican Party and his religion was Presbyterian.[1]

Later life and death

Wright had heart trouble starting in January 1894.[3] He gave up business at that time. During the summer he spent time cruising on the yacht Yampa with his wife and stepdaughter.[20] He returned to work in October. He died at an elevated railroad train station in New York City on November 12, 1894.[4] Wright was 58 years old.[21] He is buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in New York City.[22] Wright's estate was estimated to be $20,000,000 of which most went to his wife and his sister.[23] The referee for his Will decided that $100,000 was to be given to the New York Public Library which took over the old Washington Heights Free Library. Also $580,000 was given from his Will to the Knickerbocker Hospital (known as the J. Hood Wright Hospital).[24]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 White 1947, p. 443.

- ↑ Rhodes Journal 1894, p. 1302.

- 1 2 3 4 "J. Hood Wright Dead". The Sun, page 1. New York City. 13 Nov 1894 – via Newspapers.com

- 1 2 3 4 Railway World 1894, p. 909.

- ↑ Shaw 2016, p. 65.

- ↑ "Notable Nuptials". The Times, page 2. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. March 2, 1881 – via Newspapers.com

- ↑ "Flowera at a Wedding". The Wyandott Herald, page 1. Kansas City, Kansas. March 17, 1881 – via Newspapers.com

- ↑ "Flowers at a Wedding / Philadelphia Times". The New West, page 6. Cimarron, Kansas. March 26, 1881 – via Newspapers.com

- ↑ "Flowers at a Wedding". The Kansas Sentinel, page 3. Emporia, Kansas. March 16, 1881 – via Newspapers.com

- ↑ "Messrs, Mitchell, Vance & Co". The Sun, page 12. New York, New York. September 27, 1885 – via Newspapers.com

At an early stage in his wonderfully successful experiments at Menlo Park Mr. Edison turned to this firm, and they supplied him with his first permanent fixtures. From this initial step all along the line of progress to the present day, Mitchell, Vance & Co. have given their attention to electric light fixtures, and their business in these articles has developed to proportions of great magnitude. They manufacture lamps and fixtures for all the incandescent systems operated in this country, in addition to the combination fixtures for the use of both gas and electric light, besides doing a large export trade with South America and elsewhere. The first private residence lighted by the incandescent system, that of Mr. J. Hood Wright, of Drexel, Morgan & Co. was supplied with fixtures by this firm.

- ↑ Jones 1908, p. 121.

- ↑ New York Great Industries 1884, p. 96.

- ↑ Slesin 1992, p. 256.

- 1 2 Kane 1997, p. 221.

- ↑ Klein 1976, p. 170.

- ↑ Cawthorne, Douglas (October 24, 2017). "Cragside – "The Palace of a Modern Magician"". Digital Building Heritage Group. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

...he personally supervised the installation of his vacuum incandescent filament bulbs at Cragside in December 1880.

- ↑ Hannah 1979, p. 4.

- ↑ Ellis 2011, p. 276.

- ↑ "An Interesting Decision". The Evening Times, page 4. Sayre, Pennsylvania. 24 Apr 1943 – via Newspapers.com

- ↑ "Niece of H.C. Robinson Engaged". The Evening Journal, page 3. Wilmington, Delaware. July 9, 1894 – via Newspapers.com

- ↑ Hall 1895, p. 746.

- ↑ "J.H. Wright's Will". The World, p. 1. New York City. November 20, 1894.

- ↑ "Left an Estate of $20,000,000". The Daily Times, page 1. Davenport, Iowa. 22 Nov 1894 – via Newspapers.com

- ↑ "Public Library Gets Legacy of $100,000". The New York Times. New York City. August 9, 1915.

Sources

- Ellis, Edward Robb (20 September 2011). The Epic of New York City. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03053-8.

J. Pierpont Morgan, the financier, always welcomed new ideas. In January, 1881, he went to New Jersey to find out for himself if Edison's lights could be used to illuminate private homes. Edison convinced Morgan that an electric lighting system could be installed in a house. The banker promised that when he moved to 219 Madison Avenue, he would buy an Edison system. Before Morgan changed residences, however, James Hood Wright had installed a generating plant in his home in the Fort Washington section of Manhattan.

- Hall, Henry (1895). Volume 1, Successful Men of Affairs. New York tribune.

- Hannah, Leslie (17 June 1979). Electricity Before Nationalisation. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-349-03443-7.

In December 1880 the shipbuilding magnate Sir William Armstrong installed Swan lamps in his house at Cragside, Northumberland, powering them from a water-drive generator;

- Jones, Francis Arthur (1908). Thomas Alva Edison. T. Y.Crowell & Company.

The first private residence to be lighted by Edison lamps was that of J. Hood Wright, New York.

- Kane, Joseph Nathan (December 1, 1997). Famous First Facts (5th ed.). New York, NY: H. W. Wilson Company. ISBN 978-0824209308.

The first electric light from a power plant in a residence was generated by an independent plant installed in the home of James Hood Wright in the Fort Washington section of New York City sometime before December 1881.

- Klein, Maury (1976). American industrial cities, 1850-1920. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-563880-8.

James Hood Wright of Fort Washington, New York, won acclaim in December, 1881, as the first citizen to light his house by connection to a central power station.

- New York Great Industries (1884). New York Great Industries. Historical Publishing Company.

They fitted up the first private residence lit by the incandescent system, that of Mr. J. Hood Wright, of Drexel, Morgan & Co., and from that time on have had a series of orders for their superior art fixtures for the electric light, among other mansions so supplied being those of Mr. J. W. Doane of Chicago, the Messrs. Keith, Mr. Marshall Field, of Chicago, the Bemis & McAvoy Brewery of Chicago.

- Railway World (1894). Railway World.

- Rhodes Journal (1894). Rhodes' Journal of Banking. B. Rhodes & Company.

- Shaw, Quincy (2016). Edison. New Word City. ISBN 978-1-61230-970-5.

- Slesin, Suzanne (1992). New York style. Clarkson Potter Publishers.

1881 Incandescent Innovation: First Electrically Lighted House – Banker James Hood Wright installs Thomas Edison's newly invented electric lights in his suburban mansion on West 176th Street in Washington Heights.

- White, James T. (1947). National Cyclopaedia. James T. White & Company.