Jack Churchill

| Lieutenant-Colonel Jack Churchill DSO & Bar, MC & Bar | |

|---|---|

"Mad Jack" Churchill | |

| Birth name | John Malcolm Thorpe Fleming Churchill |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Born |

16 September 1906 Colombo, Ceylon[1] |

| Died |

8 March 1996 (aged 89) Surrey, England |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Lieutenant-Colonel |

| Unit | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | |

John Malcolm Thorpe Fleming Churchill, DSO & Bar, MC & Bar (16 September 1906 – 8 March 1996), was a British Army officer who fought throughout the Second World War armed with a longbow, bagpipes, and a basket-hilted Scottish broadsword.

Nicknamed "Fighting Jack Churchill" and "Mad Jack", he was known for the motto: "Any officer who goes into action without his sword is improperly dressed."

Early life

Churchill was born at Colombo, Sri Lanka (then Ceylon)[2] to Alec Fleming "Alex" Churchill (1876–1961), later of Hove, East Sussex[3] and Elinor Elizabeth, daughter of John Alexander Bond Bell, of Kelnahard, County Cavan, Ireland, and of Dimbula, Ceylon. Alec, of a family long settled at Deddington, Oxfordshire, had been District Engineer in the Ceylon Civil Service, in which his father, John Fleming Churchill (1829–1894), had also served.[4][5][6] Soon after Jack's birth, the family returned to Dormansland, Surrey, where his younger brother, Major-General Thomas Bell Lindsay Churchill (1907–1990), C.B., C.B.E., M.C.[7] was born. In 1910, the Churchills moved to Hong Kong when Alec Fleming Churchill was appointed as Director of Public Works; he also served as a member of the Executive Council. The Churchills' third and youngest son, Robert Alec Farquhar Churchill—later a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy and Fleet Air Arm—was born in Hong Kong in 1911. The family returned to England in 1917.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

Churchill was educated at King William's College on the Isle of Man. He graduated from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst in 1926 and served in Burma with the Manchester Regiment. He enjoyed riding a motorbike while in Burma.[14]

Churchill left the army in 1936 and worked as a newspaper editor in Nairobi, Kenya, and as a male model.[14] He used his archery and bagpipe talents to play a small role in the 1924 film, The Thief of Bagdad[15] and also appeared in the 1938 film, A Yank at Oxford.[14] He took second place in the 1938 military piping competition at the Aldershot Tattoo.[14] In 1939, he represented Great Britain at the World Archery Championships in Oslo.[14]

Second World War

France (1940)

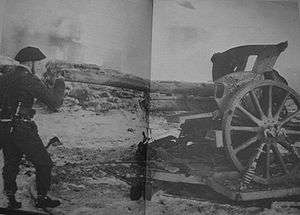

Churchill resumed his commission after Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, and was assigned to the Manchester Regiment, which was sent to France in the British Expeditionary Force. In May 1940, Churchill and some of his men ambushed a German patrol near L'Épinette (near Richebourg, Pas-de-Calais). Churchill gave the signal to attack by raising his claymore. Jack managed to start the ambush by killing one of the Germans with his longbow, proceeded by his men opening fire on the remaining Germans. After fighting at Dunkirk, he volunteered for the Commandos.

Jack's younger brother, Thomas Churchill, also served with and led a Commando brigade during the war.[16] After the war, Thomas wrote a book, Commando Crusade, that details some of the brothers' experiences during the war.[17] Their youngest brother, Robert, also known as 'Buster', served in the Royal Navy and was killed in action in 1942.[18]

Norway (1941)

Churchill was second in command of No. 3 Commando in Operation Archery, a raid on the German garrison at Vågsøy, Norway, on 27 December 1941.[19] As the ramps fell on the first landing craft, he leapt forward from his position playing "March of the Cameron Men"[20] on his bagpipes, before throwing a grenade and charging into battle. For his actions at Dunkirk and Vågsøy, Churchill received the Military Cross and Bar.

Italy (1943)

In July 1943, as commanding officer, he led 2 Commando from their landing site at Catania in Sicily with his trademark Scottish broadsword slung around his waist, a longbow and arrows around his neck and his bagpipes under his arm,[21] which he also did in the landings at Salerno.

Leading 2 Commando, Churchill was ordered to capture a German observation post outside the town of Molina, controlling a pass leading down to the Salerno beachhead.[22] With the help of a corporal, he infiltrated the town and captured the post, taking 42 prisoners including a mortar squad. Churchill led the men and prisoners back down the pass, with the wounded being carried on carts pushed by German prisoners. He commented that it was "an image from the Napoleonic Wars."[22] He received the Distinguished Service Order for leading this action at Salerno.[23]

Churchill later walked back to the town to retrieve his sword, which he had lost in hand-to-hand combat with the German regiment. On his way there, he encountered a disoriented American patrol, mistakenly walking towards enemy lines. When the NCO in command of the patrol refused to turn around, Churchill told them that he was going his own way and that he wouldn't come back for a "bloody third time".[8]

Yugoslavia (1944)

As part of Maclean Mission (Macmis), in 1944, he led the Commandos in Yugoslavia, where they supported Josip Broz Tito's Partisans from the Adriatic island of Vis.[24] In May he was ordered to raid the German held island of Brač. He organised a "motley army" of 1,500 Partisans, 43 Commando and one troop from 40 Commando for the raid. The landing was unopposed but, on seeing the eyries from which they later encountered German fire, the Partisans decided to defer the attack until the following day. Churchill's bagpipes signalled the remaining Commandos to battle. After being strafed by an RAF Spitfire, Churchill decided to withdraw for the night and to re-launch the attack the following morning.[25]

Capture (1944)

The following morning, one flanking attack was launched by 43 Commando with Churchill leading the elements from 40 Commando. The Partisans remained at the landing area. Only Churchill and six others managed to reach the objective. A mortar shell killed or wounded everyone but Churchill, who was playing "Will Ye No Come Back Again?" on his pipes as the Germans advanced. He was knocked unconscious by grenades and captured.[25] He was later flown to Berlin for interrogation and then transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp.[26]

In September 1944, Churchill and a Royal Air Force officer, Bertram James, crawled under the wire, through an abandoned drain and attempted to walk to the Baltic coast. They were captured near the German coastal city of Rostock, a few kilometres from the sea.

In late April 1945, Churchill and about 140 other prominent concentration camp inmates were transferred to Tyrol, guarded by SS troops.[27] A delegation of prisoners told senior German army officers they feared they would be executed. A German army unit commanded by Captain Wichard von Alvensleben moved in to protect the prisoners. Outnumbered, the SS guards moved out, leaving the prisoners behind.[27] The prisoners were released and, after the departure of the Germans, Churchill walked 150 kilometres (93 mi) to Verona, Italy, where he met an American armoured unit.[26]

Burma (1945)

As the Pacific War was still on, Churchill was sent to Burma,[26] where some of the largest land battles against Japan were being fought. By the time Churchill reached India, Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been bombed and the war ended. Churchill was said to be unhappy with the sudden end of the war, saying: "If it wasn't for those damn Yanks, we could have kept the war going another 10 years!"[26]

Post-World War Two

British Palestine

After the Second World War ended, Churchill qualified as a parachutist and transferred to the Seaforth Highlanders. He was soon posted to Mandatory Palestine as executive officer of the 1st Battalion, the Highland Light Infantry.[26]

In the spring of 1948, just before the end of the British mandate in the region, he became involved in another conflict. Along with twelve of his soldiers, he attempted to assist the Hadassah medical convoy that came under attack by Arab forces.[26] Churchill was one of the first men on the scene and banged on a bus, offering to evacuate members of the convoy in an APC, in contradiction to the British military orders to keep out of the fight. His offer was refused in the belief that the Jewish Haganah would come to their aid in an organised rescue.[28] When no relief arrived, Churchill and his twelve men provided cover fire against the Arab forces.[29][30][31] Two of the convoy trucks were caught on fire, and 77 of the 79 people inside of them were killed.[30] The event is known today as the Hadassah medical convoy massacre.

Of the experience he said: "About one hundred and fifty insurgents, armed with weapons varying from blunder-busses and old flintlocks to modern Sten and Bren guns, took cover behind a cactus patch in the grounds of the American Colony ... I went out and faced them." "About 250 rifle-men were on the edge of our property shooting at the convoy.... I begged them to desist from using the grounds of the American Colony for such a dastardly purpose."[29][30][31]

After the massacre, he co-ordinated the evacuation of 700 Jewish doctors, students and patients from the Hadassah hospital on the Hebrew University campus on Mount Scopus in Jerusalem, where the convoy had been headed[26] In his honor, the street leading to the hospital was named Churchill Boulevard.

Further film appearance

In 1952, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer produced the film Ivanhoe shot in Britain featuring Churchill's old rowing companion, Robert Taylor. The studio hired Churchill to appear as an archer, shooting from the walls of Warwick Castle.

Australia and surfing

In later years, Churchill served as an instructor at the land-air warfare school in Australia, where he became a passionate devotee of the surfboard. Back in Britain, he was the first man to ride the River Severn's five-foot tidal bore and designed his own board.[26] During this time back in Britain, he worked at a desk job in the army.[14]

Retirement (1959–1996)

He retired from the army in 1959, with two awards of the Distinguished Service Order. In retirement, his eccentricity continued. He startled train conductors and passengers by throwing his briefcase out of the train window each day on the ride home. He later explained that he was tossing his case into his own back garden so he would not have to carry it from the station.[26] He also enjoyed sailing coal-fired ships on the Thames and playing with radio-controlled model warships.[14]

Death

Churchill died on 8 March 1996 at 89 years old, in the county of Surrey.[10]

In March 2014, the Royal Norwegian Explorers Club published a book that featured Churchill, naming him as one of the finest explorers and adventurers of all time.[32]

Family

Churchill married Rosamund Margaret Denny, the daughter of Sir Maurice Edward Denny and granddaughter of Sir Archibald Denny, on 8 March 1941.[33] They had two children, Malcolm John Leslie Churchill, born 11 November 1942, and Rodney Alistair Gladstone Churchill, born 4 July 1947.[33] Jack was not a direct relative to Winston Churchill. Whilst the earliest ancestor (Jasper Churchill, fl. 1585) of the Dukes of Marlborough, from whom Winston Churchill descended, were of Dorset,[34] Jack Churchill's family has been traced back to Oxfordshire yeomen in the fifteenth century. [35][36]

Awards

- Distinguished Service Order with bar

- Military Cross with bar

- 1939–45 Star

- Italy Star

- Burma Star

- War Medal 1939–1945

See also

- Bill Millin – another bagpiper during World War II

- Digby Tatham-Warter

Notes

- ↑ The Churchill Chronicles, Maj.-Gen. Thomas B. L. Churchill, C.B., C.B.E., M.C., First Impressions, 1986, p. 70, 89 URL= http://www.deddingtonhistory.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/12912/ChurchillChroniclescilckablecontentsjan15.pdf Date accessed= 6 August 2018

- ↑ The Churchill Chronicles, Maj.-Gen. Thomas B. L. Churchill, C.B., C.B.E., M.C., First Impressions, 1986, p. 70, 89 URL= http://www.deddingtonhistory.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/12912/ChurchillChroniclescilckablecontentsjan15.pdf Date accessed= 6 August 2018

- ↑ "Alec Fleming Churchill (1876 - 1961)". WikiTree.

- ↑ The Churchill Chronicles, Maj.-Gen. Thomas B. L. Churchill, C.B., C.B.E., M.C. URL= http://www.deddingtonhistory.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/12912/ChurchillChroniclescilckablecontentsjan15.pdf Date accessed= 31 July 2018

- ↑ Churchill Graves and Memorials at Deddington URL= http://www.deddington.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/12687/ChGandMem2.pdf Date accessed= 31 July 2018

- ↑ "John Fleming Churchill (1829 - 1894)". WikiTree.

- ↑ Burke's Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage, 1999, vol. 1, p. 337

- 1 2 Maj-Gen Thomas B.L. Churchill, CB CBE MC (1986). The Churchill Chronicles: Annals of a Yeoman Family.

- ↑ "Fighting Jack Churchill survived a wartime odyssey beyond compare". WWII History Magazine. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- 1 2 "Lieutenant-Colonel Jack Churchill". London: Telegraph. 13 March 1996. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ Drury, Ian (31 December 2012). "The amazing story of Mad Jack". London: Daily Mail. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

- ↑ http://www.procomtours.com/jack_churchill.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The British Soldier Who Killed Nazis with a Sword and a Longbow". VICE.

- ↑ Matinee, Classics. "The Thief of Bagdad (1924)". Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ "Generals of World War II". Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ↑ "Commando Crusade".

- ↑ "Lt Robert Alec Farquhar Churchill, RN Memorial". Archived from the original on 21 August 2016.

- ↑ Parker p.41

- ↑ BBC: Great Raids of World War II, Season 1, Episode 6: Arctic Commando Assault

- ↑ Parker p.133

- 1 2 Parker pp.136–137

- ↑ London Gazette

- ↑ Parker p.148

- 1 2 Parker pp. 150–152

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Smith (2005)

- 1 2 Peter Koblank: Die Befreiung der Sonder- und Sippenhäftlinge in Südtirol, Online-Edition Mythos Elser 2006 (in German)

- ↑ Dan Kurzman, Genesis: The 1948 First Arab-Israeli War, New American Library, 1970 pp.188ff.

- 1 2 Martin Levin,It Takes a Dream: The Story of Hadassah, Gefen Publishing House, 2002 p.22

- 1 2 3 Fighting Jack Churchill survived a wartime odyssey beyond compare, Robert Barr Smith, WWII History Magazine, July 2005.

- 1 2 Bertha Spafford Vester (and Evelyn Wells); 'Our Jerusalem'; Printed in Lebanon; 1950; pp. 353–376.

- ↑ Thomas, Allister (31 March 2014). "Scots sword-wielding WWII hero honoured by book". The Scotsman. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- 1 2 "- Person Page 35768". thepeerage.com.

- ↑ Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, Harper Press, 2008, p. XVII

- ↑ Burke's Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage, 1999, vol. 2, p. 1866

- ↑ The Churchill Chronicles, Thomas B. L. Churchill, pg V, 1 URL= http://www.deddingtonhistory.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/12912/ChurchillChroniclescilckablecontentsjan15.pdf Date accessed= 4 Aug 2018

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jack Churchill. |

- Kirchner, Paul (2009). More of the Deadliest Men Who Ever Lived. Paladin Press. ISBN 978-1-58160-690-4.

- Parker, John (2000). Commandos: The inside story of Britain's most elite fighting force. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 0-7537-1292-X.

- Smith, Robert Barr (July 2005). "Fighting Jack Churchill Survived A Wartime Odyssey Beyond Compare".

- "Dark Times in the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp". Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. World News. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "The Man Who Fought in WWII with a Sword and Bow".

- King-Clark, Rex (1997). Jack Churchill 'Unlimited Boldness'. Knutsford Cheshire: Fleur-de-Lys Publishing. ISBN 1-873907-06-0.