It Can't Happen Here

First edition | |

| Author | Sinclair Lewis |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Political fiction |

| Publisher | Doubleday, Doran and Company |

Publication date | October 21, 1935 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 458 pp. |

| ISBN | 045121658X |

It Can't Happen Here is a semi-satirical 1935 political novel by American author Sinclair Lewis,[1] and a 1936 play adapted from the novel by Lewis and John C. Moffitt.[2]

Published during the rise of fascism in Europe, the novel describes the rise of Berzelius "Buzz" Windrip, a demagogue who is elected President of the United States, after fomenting fear and promising drastic economic and social reforms while promoting a return to patriotism and "traditional" values. After his election, Windrip takes complete control of the government and imposes a plutocratic/totalitarian rule with the help of a ruthless paramilitary force, in the manner of Adolf Hitler and the SS. The novel's plot centers on journalist Doremus Jessup's opposition to the new regime and his subsequent struggle against it as part of a liberal rebellion.

Reviewers at the time, and literary critics ever since, have emphasized the connection with Louisiana politician Huey Long, who was preparing to run for president in the 1936 election when he was assassinated in 1935 just prior to the novel's publication.[3]

Plot

In 1936 Senator Berzelius "Buzz" Windrip, a charismatic and power-hungry politician, wins the election as President of the United States on a populist platform, promising to restore the country to prosperity and greatness, and promising each citizen $5,000 a year. Portraying himself as a champion of traditional U.S. values, Windrip defeats President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the Democratic convention, then easily beats his Republican opponent, Senator Walt Trowbridge, in the November election.

Though having previously foreshadowed some authoritarian measures in order to reorganize the United States government, Windrip rapidly outlaws dissent, incarcerates political enemies in concentration camps, and trains and arms a paramilitary force called the Minute Men, who terrorize citizens and enforce the policies of Windrip and his "corporatist" regime. One of his first acts as president is to eliminate the influence of the United States Congress, which draws the ire of many citizens as well as the legislators themselves. The Minute Men respond to protests against Windrip's decisions harshly, attacking demonstrators with bayonets. In addition to these actions, Windrip's administration, known as the "Corpo" government, curtails women's and minority rights, and eliminates individual states by subdividing the country into administrative sectors. The government of these sectors is managed by "Corpo" authorities, usually prominent businessmen or Minute Men officers.

Those accused of crimes against the government appear before kangaroo courts presided over by "military judges". Despite these dictatorial (and "quasi-draconian") measures, a majority of Americans approve of them, seeing them as necessary but painful steps to restore U.S. power. Others, those less enthusiastic about the prospect of corporatism, reassure themselves that fascism cannot "happen here", hence the novel's title.

Open opponents of Windrip, led by Senator Trowbridge, form an organization called the New Underground, helping dissidents escape to Canada in manners reminiscent of the Underground Railroad and distributing anti-Windrip propaganda. One recruit to the New Underground is Doremus Jessup, the novel's protagonist, a traditional liberal and an opponent of both Corpoism and communist theories, which Windrip's administration suppresses. Jessup's participation in the organization results in the publication of a periodical called The Vermont Vigilance, in which he writes editorials decrying Windrip's abuses of power.

Shad Ledue, the local district commissioner and Jessup's former hired man, resents his old employer and eventually discovers his actions and has Jessup sent to a concentration camp. Ledue subsequently terrorizes Jessup's family and particularly his daughter Sissy, whom he unsuccessfully attempts to seduce. Sissy does, however, discover evidence of corrupt dealings on the part of Ledue, which she exposes to Francis Tasbrough, a one-time friend of Jessup and Ledue's superior in the administrative hierarchy. Tasbrough has Ledue imprisoned in the same camp as Jessup, where inmates he had sent there organize his murder. Jessup escapes, after a relatively brief incarceration, when his friends bribe one of the camp guards. He flees to Canada, where he rejoins the New Underground. He later serves the organization as a spy in the Northeastern United States, passing along information and urging locals to resist Windrip.

In time, Windrip's hold on power weakens as the economic prosperity he promised does not materialize and increased numbers of disillusioned Americans, including Vice President Perley Beecroft, flee to both Canada and Mexico. He also angers his Secretary of State, Lee Sarason, who had served earlier as his chief political operative and adviser. Sarason and Windrip's other lieutenants, including General Dewey Haik, seize power and exile the president to France. Sarason succeeds Windrip, but his extravagant and relatively weak rule creates a power vacuum in which Haik and others vie for power. In a bloody putsch, Haik leads a party of military supporters into the White House, kills Sarason and his associates, and proclaims himself president. The two coups cause a slow erosion of Corpo power, and Haik's government desperately tries to arouse patriotism by launching an unjustified invasion of Mexico. After slandering Mexico in state-run newspapers, Haik orders a mass conscription of young American men for the invasion of that country, infuriating many who had until then been staunch Corpo loyalists. Riots and rebellions break out across the country, with many realizing that the Corpos have misled them.

General Emmanuel Coon, among Haik's senior officers, defects to the opposition with a large portion of his army, giving strength to the resistance movement. Though Haik remains in control of much of the country, civil war soon breaks out as the resistance tries to consolidate its grasp on the Midwest. The novel ends after the beginning of the conflict, with Jessup working as an agent for the New Underground in Corpo-occupied portions of southern Minnesota.

Reception

Reviewers at the time of the book's publication, and literary critics ever since, have emphasized the connection with Louisiana politician Huey Long, who was preparing to run for president in 1936.[3] According to Boulard (1998), "the most chilling and uncanny treatment of Huey by a writer came with Sinclair Lewis's It Can't Happen Here."[4] Lewis portrayed a genuine U.S. dictator on the Hitler model. Starting in 1936 the WPA, a New Deal agency, performed the stage adaptation across the country; Lewis had the goal of hurting Long's chances in the 1936 election.[3] Keith Perry argues that the key weakness of the novel is not that he decks out U.S. politicians with sinister European touches, but that he finally conceives of fascism and totalitarianism in terms of traditional U.S. political models rather than seeing them as introducing a new kind of society and a new kind of regime.[5] Windrip is less a Nazi than a con-man-plus-Rotarian, a manipulator who knows how to appeal to people's desperation, but neither he nor his followers are in the grip of the kind of world-transforming ideology like Hitler's National Socialism.[6]

Adaptations

Stage

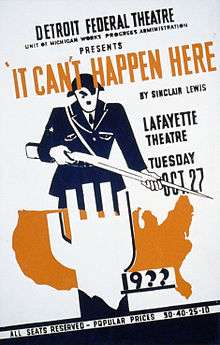

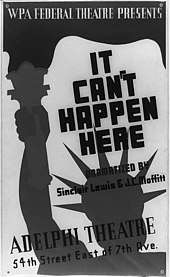

In 1936, Lewis and John C. Moffitt wrote a stage version, also titled It Can't Happen Here,[7] which is still produced. The stage version premiered on October 27, 1936 in 21 U.S. theatres in 17 states[8] simultaneously, in productions sponsored by the Federal Theater Project.

The San Francisco theater company, The Z Collective, adapted the novel for the stage, producing it both in 1989 and 1992. In 2004, The Z Space Studio adapted the Collective's script into a radio drama, which was broadcast on the Pacifica radio network on the anniversary of the Federal Theater Project's original premiere.

A new stage adaptation by Tony Taccone and Bennett S. Cohen premiered at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre in September 2016.[9]

Film

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) purchased the rights in late 1935 for a reported $200,000[10] from seeing the galley proofs[11] with Lucien Hubbard (Wings) as the producer. By early 1936, screenwriter Sidney Howard completed an adaptation, his third of Lewis' novels. J. Walter Ruben was named to direct the film with the cast headed by Lionel Barrymore, Walter Connolly, Virginia Bruce and Basil Rathbone.[12] But studio head Louis B. Mayer citing costs, indefinitely postponed production, to the publicly announced pleasure of the Nazi regime in Germany. Lewis and Howard countered that financial reason with information pointing to Berlin's and Rome's influence on movies. Will H. Hays, responsible for the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code, had notified Mayer of potential problems in the German market. Joseph Breen, head of the Production Code Administration department under Hays, thought the script was too "anti-fascist" and "so filled with dangerous material".[13][14][15] In December 1938, Charlie Chaplin announced his next movie would satirize Hitler (The Great Dictator).[16] MGM's Hubbard "dusted off the script"[17] in January, but the "idea of a dictator ruling America" had now been discussed in public for years. Hubbard rewrote a new climax, "showing a dictatorship in Washington and showing it being kicked out by disgruntled Americans as soon as they realized what had happened." The film was placed back on the production schedule for the third time with shooting starting in June and Lewis Stone playing Doremus Jessup.[18] However by July, MGM "admitted it would not make the movie after all"[19] to some criticism.[20]

Television

A 1968 television movie Shadow on the Land (alternate title: United States: It Can't Happen Here) was produced by Screen Gems as a pilot for a series loosely based on this book.

Inspired by the book, director–producer Kenneth Johnson wrote an adaptation titled Storm Warnings in 1982. The script was presented to NBC for production as a television miniseries, but NBC executives rejected the initial version, claiming it was too cerebral for the average American viewer. To make the script more marketable, the American fascists were re-cast as man-eating extraterrestrials, taking the story into the realm of science fiction. The revised story became the miniseries V, which premiered May 3, 1983.[21]

Legacy

From the beginning, It Can't Happen Here has been used as a cautionary tale starting with the 1936 presidential election and potential candidate Huey Long.

In retrospect, FDR's internment of Japanese Americans during World War II is used as an example of "It can happen here".[22]

Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention released their first album Freak Out! in 1966 with the song, "It Can't Happen Here".[23][24]

In May 1973, in the middle of Nixon's Watergate scandal, Knight Newspapers published an ad in theirs and others publications, headlined with "It Can't Happen Here" and talking about the importance of free press. “There is a struggle going on in this country. It is not just a fight by reporters and editors to protect their sources. It is a fight to protect the public's right to know... It can't happen here as long as the press remains an open conduit through which public information flows."[25] Herbert Mitgang in his op-ed piece said "The headline of this ad is the title of a novel that keeps insinuating itself these days, not because of its literary qualities but because of its prescience." And that Lewis' point was "that home‐grown hypocrisy leads to a nice brand of home‐grown authoritarianism."[25]

The non-fiction book It Can Happen Here: Authoritarian Peril in the Age of Bush (2007) frequently quotes Lewis's book in relation to the presidency of George W. Bush.[26]

A number of writers have compared the demagogue Buzz Windrip to Donald Trump. Michael Paulson wrote in The New York Times that the Berkeley Repertory Theatre's rendition of the play aimed to provoke discussion about Trump's presidential candidacy.[27] Jules Stewart discussed the similarities between Trump's America with the country as depicted in the book in an article in The Guardian.[28] Malcolm Harris, in Salon stated that "Like Trump, Windrip uses a lack of tact as a way to distinguish himself" and that "The social forces that Windrip and Trump invoke aren’t funny, they’re murderous."[29] In the Washington Post, Carlos Lozada also compared Trump to Windrip, opining that "it is impossible to miss the similarities between Trump and totalitarian figures in American literature."[30] Jacob Weisberg in Slate stated that "You can’t read Lewis’ novel today without flashes of Trumpian recognition."[31] Following the results of the 2016 United States presidential election, sales of It Can't Happen Here surged significantly, and it appeared on Amazon.com's list of bestselling books.[32]

In 2018, Can It Happen Here?, a collection of essays about the prospect of authoritarianism in the United States, edited by Cass Sunstein, was published by HarperCollins.[33]

See also

- The Iron Heel – a 1908 American dystopian novel by Jack London

- In the Second Year – Storm Jameson's 1936 book about a fascist Britain

- If Day – a 1942 simulated Nazi German invasion and occupation of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

- It Happened Here – a black-and white 1964 British World War II film

- V for Vendetta – a British graphic novel about a terrorist overthrowing a post-apocalyptic fascist Britain

- The Handmaid's Tale – a 1985 work of dystopian fiction set in a near-future fundamentalist New England

- The Plot Against America – a 2004 alternate history novel in which Charles Lindbergh defeats Roosevelt in 1940 and begins antisemitic and pro-German policies

- It Can Happen Here: Authoritarian Peril in the Age of Bush – a 2007 nonfiction book

- Can It Happen Here?: Authoritarianism in America — a 2018 collection of essays solicited by Cass Sunstein

References

- ↑ Sinclair Lewis (1935). "It Can't Happen Here". gutenberg.net.au. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ↑ Apicella, John (9 September 2012). "IT CAN'T HAPPEN HERE and the Federal Theater Project". Retrieved 15 August 2018 – via YouTube.

- 1 2 3 Perry 2004, p. 62.

- ↑ Boulard 1998, p. 115.

- ↑ Perry 2004.

- ↑ See also Lingeman 2005, pp. 400–408

- ↑ The Broadway League, IBdB.

- ↑ Flanagan 1940.

- ↑ Etheridge, Tim (2016-03-28). "Berkeley Rep Announces 2016-17 Season Opener: Sinclair Lewis' Classic Novel It Can't Happen Here" (PDF) (press release). Berkeley Repertory Theatre. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ↑ Vasey, Ruth. The World According to Hollywood, 1918-1939. p. 205.

- ↑ ""It Can't Happen Here" May Happen Very Soon". Santa Cruz Sentinel from Santa Cruz, California. February 20, 1936.

- ↑ "The Film Daily". archive.org. February 4, 1936.

- ↑ Bald, Margaret; Karolides, Nicholas J. (2006). Literature Suppressed on Political Grounds. Infobase Publishing. pp. 262–267. ISBN 9780816071517. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ David Mikies "Hollywood’s Creepy Love Affair With Adolf Hitler, in Explosive New Detail", Tablet, 10 June 2013

- ↑ Green, Jonathon; Karolides, Nicholas J. (2005). Encyclopedia of Censorship. Infobase Publishing. p. 324. ISBN 9781438110011. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Next Chaplin Film Will Be Fascist Blow". Madera Tribune. 16 December 1938.

- ↑ ""The Dictator"". The New Yorker. January 28, 1939.

- ↑ "Pittsburgh Post-Gazette from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on June 2, 1939 · Page 10". Newspapers.com. June 2, 1939. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ "Entertainment vs. Propaganda". Shamokin News-Dispatch from Shamokin, Pennsylvania. July 13, 1939.

- ↑ "Film Company Criticized for Dropping "it Can't Happen Here". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. July 6, 1939.

- ↑ Simpson.

- ↑ "California Historical Society: It Can't Happen Here - Executive Order 9066 Revisited". California Historical Society. 2017-01-05. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ↑ Crandell, Ben (January 10, 2017). "Frank talk about Dweezil Zappa's Culture Room show". southflorida.com. Retrieved 2018-08-15.

- ↑ Courrier, Kevin (March 10, 2013). "American Composer: Frank Zappa's Understanding America". www.criticsatlarge.ca. Retrieved 2018-08-15.

- 1 2 Mitgang, Herbert (20 May 1973). "Babbitt in the White House". The New York Times.

- ↑ Levin, Josh (2009-08-06). "How Is America Going To End?". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 2018-06-26.

- ↑ Paulson, Michael (2016-09-25). "A Play Timed to Trump's Candidacy Asks What If". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-10-08.

Some, like Berkeley Rep, explicitly aim to prompt discussion about Donald J. Trump

- ↑ Stewart, Jules (2016-10-09). "The 1935 novel that predicted the rise of Donald Trump". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-10-24.

- ↑ Malcolm Harris. "It really can happen here: The novel that foreshadowed Donald Trump’s authoritarian appeal". Salon, September 29, 2015.

- ↑ Carlos Lozada. "How does Donald Trump stack up against American literature’s fictional dictators? Pretty well, actually." The Washington Post, June 9, 2016.

- ↑ Jacob Weisberg. "An Eclectic Extremist: Donald Trump’s distinctly American authoritarianism draws equally from the wacko right and wacko left." Slate.

- ↑ Selter, Brian (January 28, 2017). "Amazon's best-seller list takes a dystopian turn in Trump era". CNN.com. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ↑ "CAN IT HAPPEN HERE? Authoritarianism in America". Kirkus Reviews. November 28, 2017. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

Bibliography

- Boulard, Garry (1998). Huey Long Invades New Orleans: The Siege of a City, 1934–36.

- Flanagan, Hallie (1940). Arena: The Story of the Federal Theatre. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

- Lingeman, Richard R. (2005). Sinclair Lewis: Rebel from Main Street. St. Paul, Minn: Borealis Books. ISBN 978-0-87351-541-2.

- Perry, Keith (2004). The Kingfish in Fiction: Huey P. Long and the Modern American Novel.

- Simpson, MJ. "Kenneth Johnson interview". MJSimpson.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

External links

- Bibliowiki has original media or text related to this article: It Can't Happen Here (in the public domain in Canada)

- It Can't Happen Here at Faded Page (Canada)

- Sinclair Lewis. "It Can't Happen Here". gutenberg.net.au.

- Bateman, Jodey. "Book Review: It Can't Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis". motherbird.com. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- Public Enemy by Joe Keohane, Boston Globe, December 18, 2005.

- "California Reads Curriculum Guide - It Can't Happen Here" (PDF). California Humanities.

- Macy Donyce Jones. Precarious Democracy: "It Can't Happen Here" as the Federal Theatre's Site of Mass Resistance - Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Doctoral Dissertation 2017-11-12