Iron-deficiency anemia

| Iron-deficiency anemia | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Iron-deficiency anaemia |

| |

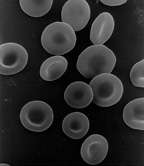

| Red blood cells | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Feeling tired, weakness, shortness of breath, confusion, pallor[1] |

| Complications | Heart failure, arrhythmias, frequent infections[2] |

| Causes | Iron deficiency[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests[4] |

| Treatment | Dietary changes, medications, surgery[3] |

| Medication | Iron supplements, vitamin C, blood transfusions[5] |

| Frequency | 1.48 billion (2015)[6] |

| Deaths | 54,200 (2015)[7] |

Iron-deficiency anemia is anemia caused by a lack of iron.[3] Anemia is defined as a decrease in the number of red blood cells or the amount of hemoglobin in the blood.[3][8] When onset is slow, symptoms are often vague, including feeling tired, weakness, shortness of breath, or poor ability to exercise.[1] Anemia that comes on quickly often has greater symptoms, including: confusion, feeling like one is going to pass out, and increased thirst.[1] There needs to be significant anemia before a person becomes noticeably pale.[1] Problems with growth and development may occur in children.[3] There may be additional symptoms depending on the underlying cause.[1]

Iron-deficiency anemia is usually caused by blood loss, insufficient dietary intake, or poor absorption of iron from food.[3] Sources of blood loss can include heavy periods, childbirth, uterine fibroids, stomach ulcers, colon cancer, and urinary tract bleeding.[9] A poor ability to absorb iron may occur as a result of Crohn's disease or a gastric bypass.[9] In the developing world, parasitic worms, malaria, and HIV/AIDS increase the risk.[10] Diagnosis is generally confirmed by blood tests.[4]

Prevention is by eating a diet high in iron or iron supplementation in those at risk.[11] Treatment depends on the underlying cause and may include dietary changes, medications, or surgery.[3] Iron supplements and vitamin C may be recommended.[5] Severe cases may be treated with blood transfusions or iron injections.[3]

Iron-deficiency anemia affected about 1.48 billion people in 2015.[6] A lack of dietary iron is estimated to cause approximately half of all anemia cases globally.[12] Women and young children are most commonly affected.[3] In 2015 anemia due to iron deficiency resulted in about 54,000 deaths – down from 213,000 deaths in 1990.[7][13]

Signs and symptoms

Iron-deficiency anemia is characterized by the sign of pallor (reduced oxyhemoglobin in skin or mucous membranes), and the symptoms of fatigue, lightheadedness, and weakness. None of these symptoms (or any of the others below) are sensitive or specific. Pallor of mucous membranes (primarily the conjunctiva) in children suggests anemia with the best correlation to the disease, but in a large study was found to be only 28% sensitive and 87% specific (with high predictive value) in distinguishing children with anemia [hemoglobin (Hb) < 11.0 g/dl] and 49% sensitive and 79% specific in distinguishing severe anemia (Hb < 7.0 g/dl).[14] Thus, this sign is reasonably predictive when present, but not helpful when absent, as only one-third to one-half of children who are anemic (depending on severity) will show pallor.

Because iron-deficiency anemia tends to develop slowly, adaptation occurs to the systemic effects that anemia causes, and the disease often goes unrecognized for some time.[15] In severe cases, dyspnea can occur.[16] Pica may also develop; pagophagia has been suggested to be "the most specific for iron deficiency."[15]

Other possible symptoms and signs of iron-deficiency anemia include:[3][15][16][17]

- Irritability

- Angina

- Palpitations

- Breathlessness

- Tingling, numbness, or burning sensations

- Glossitis (inflammation or infection of the tongue)

- Angular cheilitis (inflammatory lesions at the mouth's corners)

- Koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails) or nails that are brittle

- Poor appetite

- Dysphagia due to formation of esophageal webs (Plummer-Vinson syndrome)

- Restless legs syndrome[18]

Child development

Iron-deficiency anemia is associated with poor neurological development, including decreased learning ability and altered motor functions.[19][20] Causation has not been established, but there is a possible long-term impact from these neurological issues.[20]

Cause

A diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia requires further investigation into its cause.[21] It can be caused by increased iron demand, increased iron loss, or decreased iron intake.[22] For instance, chronic gastrointestinal blood loss can be considered, which could be linked to a possible malignancy.[21] In babies and adolescents, rapid growth may outpace dietary intake of iron and result in deficiency in the absence of disease or a grossly abnormal diet.[22] In women of childbearing age, heavy menstrual periods can also cause iron-deficiency anemia.[21]

Children who are at risk for iron-deficiency anemia include:[23]

- Preterm infants

- Low birth weight infants

- Infants fed with cow milk under 12 months of age

- Breastfed infants who have not received iron supplementation after age 6 months, or those receiving non-iron-fortified formulas

- Children between the ages of 1 to 5 years old who receive more than 24 ounces (700 mL) of cow milk per day

- Children with low socioeconomic status

- Children with special health care needs

Parasitic disease

The leading cause of iron-deficiency anemia worldwide is a parasitic disease known as a helminthiasis caused by infestation with parasitic worms (helminths); specifically, hookworms, which include Ancylostoma duodenale, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and Necator americanus, are most commonly responsible for causing iron-deficiency anemia.[21][24] The World Health Organization estimates that "approximately two billion people are infected with soil-transmitted helminths worldwide."[25] Parasitic worms cause both inflammation and chronic blood loss by binding to a human's small-intestinal mucosa, and through their means of feeding and degradation, they can ultimately cause iron-deficiency anemia.[24][15]

Blood loss

Blood contains iron within red blood cells, so blood loss leads to a loss of iron. There are several common causes of blood loss. Women with menorrhagia (heavy menstrual periods) are at risk of iron-deficiency anemia because they are at higher-than-normal risk of losing a larger amount blood during menstruation than is replaced in their diet. Slow, chronic blood loss within the body — such as from a peptic ulcer, angiodysplasia, inflammatory bowel disease, a colon polyp or gastrointestinal cancer (e.g., colon cancer), or excessively heavy menstrual periods — can cause iron-deficiency anemia. Gastrointestinal bleeding can result from regular use of some groups of medication, such as NSAIDs (e.g. aspirin), as well as antiplatelets such as clopidogrel and anticoagulants such as warfarin; however, these are required in some patients, especially those with states causing a tendency to form blood clots.

Diet

The body normally gets the iron it requires from foods. If a person consumes too little iron, or iron that is poorly absorbed (non-heme iron), they can become iron deficient over time. Examples of iron-rich foods include meat, eggs, leafy green vegetables and iron-fortified foods. For proper growth and development, infants and children need iron from their diet.[26] A high intake of cow’s milk is associated with an increased risk of iron-deficiency anemia.[27] Other risk factors for iron-deficiency anemia include low meat intake and low intake of iron-fortified products.[27]

Iron malabsorption

Iron from food is absorbed into the bloodstream in the small intestine, primarily in the duodenum.[28] Iron malabsorption is a less common cause of iron-deficiency anemia, but many gastrointestinal disorders can reduce the body's ability to absorb iron.[29] There are different mechanisms that may be present.

In celiac disease, abnormal changes in the structure of the duodenum can decrease iron absorption.[30] Abnormalities or surgical removal of the stomach can also lead to malabsorption by altering the acidic environment needed for iron to be converted into its absorbable form.[29] If there is insufficient production of hydrochloric acid in the stomach, hypochlorhydria/achlorhydria can occur (often due to chronic H. pylori infections or long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy), inhibiting the conversion of ferric iron to the absorbable ferrous iron.[30]

Pregnancy

Without iron supplementation, iron-deficiency anemia occurs in many pregnant women because their iron stores need to serve their own increased blood volume, as well as be a source of hemoglobin for the growing fetus and for placental development.[26]

Other less common causes are intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria.

Iron deficiency in pregnancy appears to cause long-term and irreversible cognitive deficits in the baby.[31]

Mechanism

Anemia can result from significant iron deficiency.[29] When the body has sufficient iron to meet its needs (functional iron), the remainder is stored for later use in cells, mostly in the bone marrow and liver.[29] These stores are called ferritin complexes and are part of the human (and other animals) iron metabolism systems.

Iron is a mineral that is important in the formation of red blood cells in the body, particularly as a critical component of hemoglobin.[21] After being absorbed in the small intestine, iron travels through blood, bound to transferrin, and eventually ends up in the bone marrow, where it is involved in red blood cell formation.[21] When red blood cells are degraded, the iron is recycled by the body and stored.[21]

When the amount of iron needed by the body exceeds the amount of iron that is readily available, the body can use iron stores (ferritin) for a period of time, and red blood cell formation continues normally.[29] However, as these stores continue to be used, iron is eventually depleted to the point that red blood cell formation is abnormal.[29] Ultimately, anemia ensues, which by definition is a hemoglobin lab value below normal limits.[29][3]

Diagnosis

Conventionally, a definitive diagnosis requires a demonstration of depleted body iron stores obtained by bone marrow aspiration, with the marrow stained for iron.[32][33] However, with the availability of reliable blood tests that can be more readily collected for iron-deficiency anemia diagnosis, a bone marrow aspiration is usually not obtained.[34] Furthermore, a study published April 2009 questions the value of stainable bone marrow iron following parenteral iron therapy.[35] Once iron deficiency anemia is confirmed, gastrointestinal blood loss is presumed to be the cause until proven otherwise since it can be caused by an otherwise asymptomatic colon cancer. Initial evaluation must include esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy to evaluate for cancer or bleeding of the gastrointestinal tract.

History

The diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia will be suggested by history that includes common causes of the condition, such as a menstruating woman or the presence of occult blood (i.e., hidden blood) in the stool.[36] A travel history to areas in which hookworms and whipworms are endemic may be helpful in guiding certain stool tests for parasites or their eggs.[37]

Although symptoms can play a role in identifying iron-deficiency anemia, these are often nonspecific symptoms, especially in mild cases, which may limit their contribution to determining the diagnosis.

Blood tests

| Change | Parameter |

|---|---|

| ↓ | ferritin, hemoglobin, MCV, MCH |

| ↑ | TIBC, transferrin, RDW, FEP |

Anemia is often discovered by routine blood tests, which generally include a complete blood count (CBC). A sufficiently low hemoglobin (Hb) by definition makes the diagnosis of anemia, and a low hematocrit value is also characteristic of anemia. Further studies will be undertaken to determine the anemia's cause. If the anemia is due to iron deficiency, one of the first abnormal values to be noted on a CBC, as the body's iron stores begin to be depleted, will be a high red blood cell distribution width (RDW), reflecting an increased variability in the size of red blood cells (RBCs).[21][15]

A low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) also appears during the course of body iron depletion. It indicates a high number of abnormally small red blood cells. A low MCV, a low mean corpuscular hemoglobin or mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCH), and the corresponding appearance of RBCs on visual examination of a peripheral blood smear narrows the problem to a microcytic anemia (literally, a "small red blood cell" anemia).[15]

The blood smear of a person with iron-deficiency anemia shows many hypochromic (pale, relatively colorless) and small RBCs, and may also show poikilocytosis (variation in shape) and anisocytosis (variation in size).[15][34] Target cells may also be seen. With more severe iron-deficiency anemia, the peripheral blood smear may show hypochromic, pencil-shaped cells and, occasionally, small numbers of nucleated red blood cells.[38] The platelet count may be slightly above the high limit of normal in iron-deficiency anemia (termed a mild thrombocytosis), but severe cases can present with thrombocytopenia (low platelet count).[39]

Iron-deficiency anemia is confirmed by tests that include serum ferritin, serum iron level, serum transferrin, and total iron binding capacity (TIBC). A low serum ferritin is most commonly found. However, serum ferritin can be elevated by any type of chronic inflammation and thus is not consistently decreased in iron-deficiency anemia.[21] Serum iron levels may be measured, but serum iron concentration is not as reliable as the measurement of both serum iron and serum iron-binding protein levels (TIBC).[17] The ratio of serum iron to TIBC (called iron saturation or transferrin saturation index or percent) is a value with defined parameters that can help to confirm the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia; however, other conditions must also be considered, including other types of anemia.[17]

Another finding that can be used is the level of free erythrocyte protoporphyrin (FEP).[40] During haemoglobin synthesis, trace amounts of zinc will be incorporated into protoporphyrin in the place of iron which is lacking. We can separate the protoporphyrin from its zinc moeity and measure it, known as the FEP, providing an indirect measurement of the zinc-protoporphyrin complex. The level of FEP is expressed in either μg/dl of whole blood or μg/dl of RBC. An iron insufficiency in the bone marrow can be detected very early by a rise in FEP.

Further testing may be necessary to differentiate iron-deficiency anemia from other disorders, such as thalassemia minor.[41] It is very important not to treat people with thalassemia with an iron supplement, as this can lead to hemochromatosis. A hemoglobin electrophoresis provides useful evidence for distinguishing these two conditions, along with iron studies.[17][42]

Screening

It is unclear if screening pregnant women for iron-deficiency anemia during pregnancy improves outcomes in the United States.[43] The same holds true for screening children who are "6 to 24 months" old.[44]

Treatment

When treating iron-deficiency anemia, considerations of the proper treatment methods are done in light of the "cause and severity" of the condition.[5] If the iron-deficiency anemia is a downstream effect of blood loss or another underlying cause, treatment is geared toward addressing the underlying cause when possible.[5] In severe acute cases, treatment measures are taken for immediate management in the interim, such as blood transfusions or even intravenous iron.[5]

Iron-deficiency anemia treatment for less severe cases includes dietary changes to incorporate iron-rich foods into regular oral intake.[5] Foods rich in ascorbic acid (vitamin C) can also be beneficial, since ascorbic acid enhances iron absorption.[5] Other oral options are iron supplements in the form of pills or drops for children.[5] The various forms of treatment are not without possible adverse effects. Iron supplementation by mouth commonly causes negative gastrointestinal effects, including constipation.[45]

As iron-deficiency anemia becomes more severe, if the anemia does not respond to oral treatments, or if the treated person does not tolerate oral iron supplementation, then other measures may become necessary.[5][45] Specifically, for those on dialysis, parenteral iron is commonly used.[45] Individuals on dialysis who are taking forms of erythropoietin or some "erythropoiesis-stimulating agent" are given parenteral iron, which helps the body respond to the erythropoietin agents and produce red blood cells.[45][46] Intravenous iron can induce an allergic response that can be as serious as anaphylaxis, although different formulations have decreased the likelihood of this adverse effect.[45]

Epidemiology

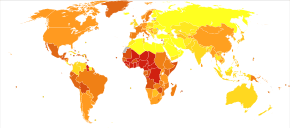

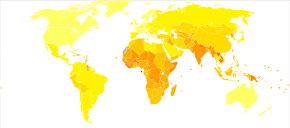

A moderate degree of iron-deficiency anemia affects approximately 610 million people worldwide or 8.8% of the population.[48] It is slightly more common in females (9.9%) than males (7.8%).[48] Mild iron deficiency anemia affects another 375 million.[48]

The prevalence of iron deficiency as a cause of anemia varies among countries; in the groups in which anemia is most common, including young children and a subset of non-pregnant women, iron deficiency accounts for a fraction of anemia cases in these groups ("25% and 37%, respectively").[49] Iron deficiency is a more common cause of anemia in other groups, including pregnant women.[50]

Within the United States, iron-deficiency anemia affects about 2% of adult males, 10.5% of Caucasian women, and 20% of African-American and Mexican-American women.[51]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Janz, TG; Johnson, RL; Rubenstein, SD (Nov 2013). "Anemia in the Emergency Department: Evaluation and Treatment". Emergency Medicine Practice. 15 (11): 1–15, quiz 15-6. PMID 24716235.

- ↑ "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Iron-Deficiency Anemia?". NHLBI. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "What Is Iron-Deficiency Anemia? - NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- 1 2 "How Is Iron-Deficiency Anemia Diagnosed?". NHLBI. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "How Is Iron-Deficiency Anemia Treated?". NHLBI. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- 1 2 GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- 1 2 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ Stedman's Medical Dictionary (28th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006. p. Anemia. ISBN 9780781733908.

- 1 2 "What Causes Iron-Deficiency Anemia?". NHLBI. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "Micronutrient deficiencies". WHO. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "How Can Iron-Deficiency Anemia Be Prevented?". NHLBI. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ Combs, Gerald F. (2012). The Vitamins. Academic Press. p. 477. ISBN 9780123819802. Archived from the original on 2017-08-18.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, Regional, and National Age-Sex Specific All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality for 240 Causes of Death, 1990-2013: a Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2012-05-15. Pallor in diagnosis of iron deficiency in children

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew (2016). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. pp. 1052–1059, 1068–1073, 2159–2164. ISBN 978-1-4557-5017-7.

- 1 2 Ferri, Fred (2018). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018. pp. 87–88, e1–e3713. ISBN 978-0-323-28049-5.

- 1 2 3 4 McPherson, Richard; Pincus, Matthew (2017). Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. pp. 84–101, 559–605. ISBN 978-0-323-29568-0.

- ↑ Rangarajan, Sunad; D'Souza, George Albert. (April 2007). "Restless legs syndrome in Indian patients having iron deficiency anemia in a tertiary care hospital". Sleep Medicine. 8 (3): 247–51. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2006.10.004. PMID 17368978.

- ↑ Kliegman, Robert; Stanton, Bonita; St Geme, Joseph; Schor, Nina (2016). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. pp. 2323–2326. ISBN 978-1-4557-7566-8.

- 1 2 Polin, Richard; Ditmar, Mark (2016). Pediatric Secrets. pp. 296–340. ISBN 978-0-323-31030-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Howard, Martin; Hamilton, Peter (2013). Haematology: An Illustrated Colour Text. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-7020-5139-5.

- 1 2 "NPS News 70: Iron deficiency anaemia". NPS Medicines Wise. October 1, 2010. Archived from the original on February 22, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ↑ American Academy of Pediatrics textbook of pediatric care. McInerny, Thomas K.,, American Academy of Pediatrics. (2nd ed.). [Elk Grove Village, IL]. ISBN 9781610020473. OCLC 952123506.

- 1 2 Broaddus, V. Courtney; Mason, Robert; Ernst, Joel, et.al. (2016). Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. pp. 682–698. ISBN 978-1-4557-3383-5.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2014-03-05. World Health Organization Fact Sheet No. 366, Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections, updated June 2013

- 1 2 "Iron deficiency anemia". Mayo Clinic. March 4, 2011. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- 1 2 Decsi, T.; Lohner, S. (2014). "Gaps in meeting nutrient needs in healthy toddlers". Ann Nutr Metab. 65 (1): 22–8. doi:10.1159/000365795. PMID 25227596.

- ↑ Yeo, Charles (2013). Shackelford's Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. pp. 821–838. ISBN 978-1-4377-2206-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Porwit, Anna; McCullough, Jeffrey; Erber, Wendy (2011). Blood and Bone Marrow Pathology. pp. 173–195. ISBN 9780702031472.

- 1 2 Feldman, Mark; Friedman, Lawrence; Brandt, Lawrence (2016). Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. pp. 297–335. ISBN 978-1-4557-4692-7.

- ↑ Lozoff, Betsy (December 1, 2007). "Iron Deficiency and Child Development". Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 28 (4): S560–S561. doi:10.1177/15648265070284S409. PMID 18297894.

- ↑ Mazza, J.; Barr, R. M.; McDonald, J. W.; Valberg, L. S. (21 October 1978). "Usefulness of the serum ferritin concentration in the detection of iron deficiency in a general hospital". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 119 (8): 884–886. PMC 1819106. PMID 737638. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ↑ Kis, AM; Carnes, M (July 1998). "Detecting Iron Deficiency in Anemic Patients with Concomitant Medical Problems". J Gen Intern Med. 13 (7): 455–61. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00134.x. PMC 1496985. PMID 9686711.

- 1 2 Kellerman, Rick; Bope, Edward (2018). Conn's Current Therapy 2018. pp. 403–405. ISBN 978-0-323-52769-9.

- ↑ Thomason, Ronald W.; Almiski, Muhamad S. (April 2009). "Evidence That Stainable Bone Marrow Iron Following Parenteral Iron Therapy Does Not Correlate With Serum Iron Studies and May Not Represent Readily Available Storage Iron". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 131 (4): 580–585. doi:10.1309/AJCPBAY9KRZF8NUC. PMID 19289594. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ↑ Brady PG (October 2007). "Iron deficiency anemia: a call for aggressive diagnostic evaluation". Southern Medical Journal. 100 (10): 966–967. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181520699. PMID 17943034. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ↑ Bennett, John; Dolin, Raphael; Blaser, Martin (2015). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, Updated Edition. pp. 3196–3198. ISBN 978-0-323-40161-6.

- ↑ Stephen J. McPhee, Maxine A. Papadakis. Current medical diagnosis and treatment 2009 page.428

- ↑ Lanzkowsky, Philip; Lipton, Jeffrey; Fish, Jonathan (2016). Lanzkowsky's Manual of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. pp. 69–83. ISBN 978-0-12-801368-7.

- ↑ Joint World Health Organization/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Technical Consultation on the Assessment of Iron Status at the Population Level (2004 : Geneva, Switzerland). (2007). Assessing the iron status of populations: including literature reviews: report of a Joint World Health Organization/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Technical Consultation on the Assessment of Iron Status at the Population Level, Geneva, Switzerland, 6–8 April 2004, 2nd ed. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/75368

- ↑ O'Connell, Theodore (2017). Instant Work-ups: A Clinical Guide to Medicine. pp. 23–31. ISBN 978-0-323-37641-9.

- ↑ Hines, Roberta; Marschall, Katherine (2018). Stoelting's Anesthesia and Co-existing Disease. pp. 477–506. ISBN 978-0-323-40137-1.

- ↑ Siu, AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force (6 October 2015). "Screening for Iron Deficiency Anemia and Iron Supplementation in Pregnant Women to Improve Maternal Health and Birth Outcomes: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 163 (7): 529–36. doi:10.7326/m15-1707. PMID 26344176.

- ↑ Siu, Albert L. (2015-10-01). "Screening for Iron Deficiency Anemia in Young Children: USPSTF Recommendation Statement". Pediatrics. 136 (4): 746–752. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-2567. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 26347426.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kasper, Dennis; Fauci, Anthony; Hauser, Stephen; Longo, Dan; Jameson, J. Larry; Loscalzo, Joseph, Dennis; Fauci, Anthony; Hauser, Stephen; Longo, Dan; Jameson, J. Larry; Loscalzo, Joseph (2015). "126". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 19e. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4.

- ↑ "KDIGO clinical practice guideline for anemia in chronic kidney disease". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. August 2012.

- ↑ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002. Archived from the original on 2013-01-16.

- 1 2 3 Vos, T; Flaxman, AD; Naghavi, M; Lozano, R; Michaud, C; Ezzati, M; Shibuya, K; Salomon, JA; et al. (Dec 15, 2012). "Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) for 1160 Sequelae of 289 Diseases and Injuries 1990-2010: a Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMID 23245607.

- ↑ Petry, Nicolai; Olofin, Ibironke; Hurrell, Richard F.; Boy, Erick; Wirth, James P.; Moursi, Mourad; Donahue Angel, Moira; Rohner, Fabian (2016-11-02). "The Proportion of Anemia Associated with Iron Deficiency in Low, Medium, and High Human Development Index Countries: A Systematic Analysis of National Surveys". Nutrients. 8 (11): 693. doi:10.3390/nu8110693.

- ↑ Sifakis, S.; Pharmakides, G. (2000-04-01). "Anemia in Pregnancy". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 900 (1): 125–136. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06223.x. ISSN 1749-6632.

- ↑ Killip, S; Bennett, JM; Chambers, MD (1 March 2007). "Iron deficiency anemia". American Family Physician. 75 (5): 671–8. PMID 17375513. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- The Importance of Iron – From IronTherapy.Org

- Interactive material on Iron Metabolism – From IronAtlas.com

- Establishing the cause of anemia – From AnaemiaWorld.com

- Handout: Iron Deficiency Anemia – From the National Anemia Action Council

- NPS News 70: Iron deficiency anaemia: NPS – Better choices, Better health – From the National Prescribing Service