Hemolysis

| Hemolysis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Pathology |

Hemolysis or haemolysis (/hiːˈmɒlɪsɪs/),[1] also known by several other names, is the rupturing (lysis) of red blood cells (erythrocytes) and the release of their contents (cytoplasm) into surrounding fluid (e.g. blood plasma). Hemolysis may occur in vivo or in vitro (inside or outside the body).

Hemolysins damage the host cytoplasmic membrane, causing cell lysis and death. The activity of these toxins is most easily observed with assays involving the lysis of red blood cells (erythrocytes). Some hemolysins attack the phospholipid of the host cytoplasmic membrane. Because the phospholipid lecithin (phosphatidylcholine) is often used as a substrate, these enzymes are called lecithinases or phospholipases. Some hemolysins affects the sterols of the host cytoplasmic membrane.[2]

Inside the body

Hemolysis inside the body can be caused by a large number of medical conditions, including many Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Staphylococcus), some parasites (e.g., Plasmodium), some autoimmune disorders (e.g., drug-induced hemolytic anemia), some genetic disorders (e.g., Sickle-cell disease or G6PD deficiency), or blood with too low a solute concentration (hypotonic to cells).

Hemolysis can lead to hemoglobinemia due to hemoglobin released into the blood plasma.

Streptococcus

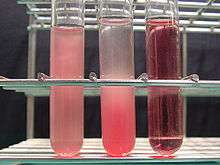

Many species of the genus Streptococcus cause hemolysis. Streptococcal bacteria species are classified according to their hemolytic properties. Note that these hemolytic properties are not necessarily present in vivo.

- Alpha-hemolytic species, including S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus mitis, S. mutans, and S. salivarius, oxidize the iron in the hemoglobin (turning it dark green in culture).

- Beta-hemolytic species, including S. pyogenes and S. agalactiae, completely rupture the red blood cells (visible as a halo in culture).

- Gamma-hemolytic, or non-hemolytic, species do not cause hemolysis and rarely cause illness.

Enterococcus

The genus Enterococcus includes lactic acid bacteria formerly classified as gamma-hemolytic Group D in the genus streptococcus (see above), including E. faecilis (S. faecalis), E. faecium (S. faecium), E. durans (S. durans), and E. avium (S. avium).

Staphylococcus

Staphylococcus is another Gram-positive cocci. S. aureus, the most common cause of "staph" infections, is frequently hemolytic on blood agar.[3]

Parasitic hemolysis

Because the feeding process of the Plasmodium parasites damages red blood cells, malaria is sometimes called "parasitic hemolysis" in medical literature.

HELLP, pre-eclampsia, or eclampsia

- See HELLP syndrome, Pre-eclampsia, and Eclampsia

Hemolytic disease of the newborn

Hemolytic disease of the newborn is an autoimmune disease resulting from the mother's antibodies crossing the placenta to the fetus.

Hemolytic anemia

Because in vivo hemolysis destroys the red blood cells, in uncontrolled chronic or severe cases it can lead to hemolytic anemia.

Hemolytic crisis

A hemolytic crisis, or hyperhemolytic crisis, is characterized by an accelerated rate of red blood cell destruction leading to anemia, jaundice, and reticulocytosis.[4] Hemolytic crises are a major concern with sickle-cell disease and G6PD deficiency.

Toxic agent ingestion or poisoning

Paxillus Involutus ingestion can cause Hemolysis.

Outside the body

In vitro hemolysis can be caused by improper technique during collection of blood specimens, by the effects of mechanical processing of blood, or by bacterial action in cultured blood specimens.

From specimen collection

Most causes of in vitro hemolysis are related to specimen collection. Difficult collections, unsecure line connections, contamination, and incorrect needle size, as well as improper tube mixing and incorrectly filled tubes are all frequent causes of hemolysis. Excessive suction can cause the red blood cells to be smashed on their way through the hypodermic needle owing to turbulence and physical forces. Such hemolysis is more likely to occur when a patient's veins are difficult to find or when they collapse when blood is removed by a syringe or a modern vacuum tube. Experience and proper technique are key for any phlebotomist or nurse to prevent hemolysis.

In vitro hemolysis during specimen collection can cause inaccurate laboratory test results by contaminating the surrounding plasma with the contents of hemolyzed red blood cells. For example, the concentration of potassium inside red blood cells is much higher than in the plasma and so an elevated potassium level is usually found in biochemistry tests of hemolyzed blood.

After the blood collection process, in vitro hemolysis can still occur in a sample due to external factors, such as prolonged storage, incorrect storage conditions and excessive physical forces by dropping or vigorously mixing the tube.

From mechanical blood processing during surgery

In some surgical procedures (especially some heart operations) where substantial blood loss is expected, machinery is used for intraoperative blood salvage. A centrifuge process takes blood from the patient, washes the red blood cells with normal saline, and returns them to the patient's blood circulation. Hemolysis may occur if the centrifuge rotates too quickly (generally greater than 500 rpm)—essentially this is hemolysis occurring outside of the body. Unfortunately, increased hemolysis occurs with massive amounts of sudden blood loss, because the process of returning a patient's cells must be done at a correspondingly higher speed to prevent hypotension, pH imbalance, and a number of other hemodynamic and blood level factors.

From bacteria culture

Visualizing the physical appearance of hemolysis in cultured blood samples may be used as a tool to determine the species of various Gram-positive bacteria infections (e.g., Streptococcus).

Nomenclature

Hemolysis is sometimes called hematolysis, erythrolysis, or erythrocytolysis. The words hemolysis (/hiːˈmɒlɪsɪs/)[1] and hematolysis (/ˌhiːməˈtɒlɪsɪs/)[6] both use combining forms conveying the idea of "lysis of blood" (hemo- or hemato- + -lysis). The words erythrolysis (/ˌɛrəˈθrɒlɪsɪs/)[7] and erythrocytolysis (/əˌrɪθroʊsaɪˈtɒlɪsɪs/)[8] both use combining forms conveying the idea of "lysis of erythrocytes" (erythro- ± cyto- + -lysis).

Erythrocytes have a short lifespan (weeks or months), and the body is always reclaiming the ones that are getting older (that is, the senescent ones) and replacing them with new ones via erythropoiesis. The breakdown and replacement together (and the rate of change) are called erythrocyte turnover. Given that the lysis of erythrocytes is therefore a normal and ongoing physiologic process, one might be prompted to say that erythrolysis or hemolysis is a normal process that happens continually in everyone. However, when these words are used, they usually mean the pathologic type of RBC lysis; that is, mentions of hemolysis without further specification indicate pathologic hemolysis.

See also

References

- 1 2 Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ↑ Brock Biology of Microorganisms 13th Edition. 2010. p. 804. ISBN 978-0-321-64963-8.

- ↑ MicrobeLibrary.org, American Society for Microbiology Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Innvista

- ↑ Capital Health

- ↑ "Hematolysis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ "erythrolysis". American Heritage Stedman's Medical Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ "erythrocytolysis". American Heritage Stedman's Medical Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

External links

- Effects of Hemolysis on Clinical Specimens

- Hemolysis at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)