Irish issue in British politics

The status of Ireland was a major issue in British politics often on for centuries. The Irish issue was the single major source of political upheaval, – and political violence, in British politics throughout the 19th century into the early 1920s. Religion was a key factor: Catholics comprise a large majority, but were impoverished and penalized and politically inert before the 1820s. In Ulster, a strong middle-class Presbyterian element had built an industrial base. Political control of Ireland was in the hands of several thousand rich English families, who owned practically all the good farmland. Most of the harsh penalties against Catholics and been lifted in the 1790s-- Catholics could vote, but they could not sit in Parliament and therefore they had little political power. In the 1820s Daniel O'Connor began mobilizing the Catholics, working at the local level with the priests, and achieved full emancipation in 1829, including the all-important right to sit in Parliament. The Young Ireland movement of the 1840s saw the emergence of a spirit of Irish nationalism, often based on Celtic traditions. The horrible great famine of 1845-1851 killed upwards of 1 million Irish men, women and children, and forced another million to migrate, especially to the United States. It was so badly handled by the British government that it left a profound residue of distrust and hatred that exacerbated every grievance that came along. It also created a strong base for Irish nationalism in the United States, that provided political and financial support until the Irish Free State was created as an independent nation in 1922. The Fenian Movement included the Fenian Brotherhood and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). It emerged in the United States in the late 1860s. It demanded independence and engaged in secret mobilization, agitation, and violence that ebbed and flowed For over a half-century. The Land League of the 1870s focused on economic issues, specifically the end of discrimination against tenant farmers by their landlords, and the ultimate ownership of the land. Violence and boycotts became unofficial weapons. Charles Stewart Parnell captained the Land League and mobilized the Catholic vote so that the Irish Parliamentary Party held the balance of power in Parliament, allowing Parnell to use disruptive tactics that kept British politics into turmoil. William E. Gladstone and his Liberal Party usually worked with Parnell in search of Home Rule. The Conservative party, representing the landlords, and with a strong base in the House of Lords, blocked Home Rule year in and year out until 1914. However the Conservatives did have a solution: use the British treasury to buy out the landlords; by 1910 most of the tenant farmers and become proprietors, and most of the landlords were gone.

Home Rule was passed in 1914, but suspended in operation during the First World War. The Irish nationalists had always ignored the Presbyterians in Ulster, but they were fiercely opposed to rule by the Catholics (" Rome Rule" they called it) and threatened their own violent rebellion. The Easter Rebellion by Catholics in 1916 was brutally crushed by the British Army, but it aroused most Catholics to discard Home Rule and demand immediate independence. The result was escalating violence against the British that was finally resolved in 1921 by partitioning Ireland into the independent Catholic-dominated Irish Free State in the south, and Northern Ireland, which remained part of the United Kingdom. The next round of troubles emerged in the 1960s, when the Catholics living in Northern Ireland could no longer tolerate the severe discrimination long imposed on them by the Protestant government. The troubles finally ended in 1998.[1]

Irish nationalism

The 19th century and early 20th century saw the rise of Irish Nationalism first among the Presbyterians and then the Catholics. The Anglicans generally were unionists who identified with British nationalism. Daniel O'Connell led a successful unarmed campaign for Catholic Emancipation. A subsequent campaign for Repeal of the Act of Union failed. Later in the century Charles Stewart Parnell and others campaigned for self government within the Union or "Home Rule". Parnell organize the Irish Catholic vote so effectively that he played a decisive role in confronting the two major parties. Starting late in the 19th century, the Conservatives adopted a new policy of buying out the rich Anglican landowners, and selling the land and very inexpensive rates to the Catholic peasants. the crisis came in 1916, with a failed Easter Rebellion. British officials crushed it so brutally, that public opinion overnight switched away from moderate provisions such as home rule,, to the demand for independence. 1916-22 was marked by severe unrest, and a series of small-scale wars. the Presbyterian based holster population broke away from predominantly Catholic South. The final solution came with partition, with independence for the primarily Catholic southern region, and integration into the United Kingdom for Ulster and the North. Ireland was scarcely an issue in British politics until the 1960s, when Northern Ireland exploded in "The Troubles" as Catholics mobilized, often using violence, to protest systematic discrimination against them. Peace was finally achieved in 1998.

18th century

For most of the 18th century, Ireland was largely quiet, and played a minor role in British politics. Between 1778 and 1793, nearly all the laws restricting Catholics in terms of worship, owning or leasing lands, education, and entry into the professions were repealed. wealthy Irish Catholics got the vote in 1793. The main remaining restriction was not being allowed to sit in Parliament. Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger took an active role in the reforms. King George III was a staunch Protestant, troubled by the reforms. He drew the line at membership in Parliament, forcing Pitt to resign in 1801.[2]

Although the Catholic majority was regaining its rights, Irish economy, politics, society, and culture was largely dominated by the Anglican landowners, who comprised the Protestant Ascendancy. There was a large Presbyterian minority in the North, who resented being pushed to the margins by the Anglicans. They took the lead in developing Irish nationalism after 1790.

Irish Rebellion of 1798

The explosion came in 1798, when a poorly organized rebellion broke out, was brutally suppressed by the British Army, but not after of thousands of people on both sides --perhaps as many as 30,000-- were massacred. London decided that the Irish Parliament, although completely controlled by the Protestant Ascendancy, could not keep order. It was dissolved, and the separate kingdom of Ireland was absorbed into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland by the Act of Union of 1800.[3]

Early 19th century

Part of the agreement which led to the 1800 Act of Union stipulated that the Penal Laws in Ireland were to be repealed and Catholic Emancipation granted. However King George III blocked emancipation, arguing that to grant it would break his coronation oath to defend the Anglican Church. A campaign under Protestant lawyer Daniel O'Connell, led to the concession of Catholic Emancipation in 1829, allowing Catholics to sit in Parliament. O'Connell then mounted an unsuccessful campaign for the Repeal of the Act of Union of 1800.

The peasants engaged in widespread secret violent threats and attacks against landlords. Repression was a popular response and required building a better policing system as realized by the Peace Preservation Corps in 1814 and the County Constabulary in 1822. The two were combined in 1836 to create the Irish Constabulary. Coercion acts were passed during times of social and political unrest and nationalist leaders often arrested, imprisoned or transported to Australia. Systematic execution was used after the Easter Rebellion of 1916, but it backfired and helped consolidate anti-British hatreds. Allowing millions to suffer in the Great Famine of 1845-51 seemed an appropriate punishment in the minds of many frustrated Englishmen, but repression ever worked well. Gladstone by 1869 proposed a gentler policy to try to resolve some of the grievances.[4]

Catholic emancipation

Great Famine

When potato blight hit the island in 1846, much of the Catholic population were short of their main food.[5][6] While enormous sums were raised by private individuals and charities, lack of adequate action let the problem become a catastrophe. The class of cottiers or farm labourers was virtually wiped out though death and emigration in what became known in Britain as 'The Irish Potato Famine' and in Ireland as the Great Hunger.

The famine and its memory permanently changed the island's demographic, political, and cultural landscape. Those who stayed and those who left in the Irish diaspora, never forgot. The horrors became a rallying point for Irish nationalist movements. The already strained between Catholics and the British Crown soured further, heightening ethnic and sectarian tensions. Republicanism became a factor.[7]

Improved conditions in rural Ireland

By the 1850s, the food supply was back to normal, and with 2 million fewer people, it did not have to stretch so far. Farms grew larger, harvests were good, prices rose, and rents were stable. Evictions became rare. Cash started flowing in from family members in the United States, including money for tickets to make it possible for more to emigrate, thereby dramatically opening opportunities for the most ambitious young people. The physical environment was upgraded – cottages were improved and enlarged, People had better clothing and supplemented the old potato diet with cereals, bread and butter, vegetables, eggs, and – on rare occasions – meat and fish. The national educational system was in operation, ending the dark era of universal illiteracy. There were more priests, and they were better educated, and more attentive to devotionalism, along with much greater respect for the papacy. The church took an active leadership role in political mobilization, deploring violence and insisting on moral behavior. The result by 1870 was a much more healthier and productive and optimistic peasantry. Farm prices declined in the 1870s, but not so much that the main gains were reversed. An enhanced sense of Irish nationalism was expressed in a Gaelic revival focused on the study of historical cultural icons, as well as a Fresh liveliness in storytelling, songs, poetry and popular culture.[8] Furthermore, new laws gave tenants better security and protections from landlords. The effectiveness of Parnell and the Irish MPs in holding the balance of power in Parliament energized politics and gave the Irish a sense of more control on their political destiny.[9]

1868 to 1900

Church of Ireland

The first premiership of Benjamin Disraeli in 1868 was short--it was dominated by the heated debate over the Church of Ireland, a Protestant church associated with the Anglican Church of England. Although Ireland was three-fourths Roman Catholic, the Protestant Church remained the established church and was funded by direct taxation. The Catholics resented that, as did the presbyterians.[10] An initial attempt by Disraeli to negotiate with his old friend Archbishop Manning the establishment of a Roman Catholic university in Dublin foundered in March when Gladstone moved resolutions to disestablish the Irish Church altogether. The proposal united the Liberals under Gladstone's leadership, while causing divisions among the Conservatives, and Disraeli's proposals all failed.[11]

Gladstone's proposals

The last phase of his Gladstone's career was devoted to the Irish question.[12] He sought repeatedly to pass a home rule bill but failed in 1886 and 1893. In the Irish Church Act of 1869, however, he led parliament to disestablish the Church of Ireland (that is the Protestant Anglican Church of the landowners, not the Catholic Church of the peasants), so that taxes were no longer collected for its benefit. In 1870 he began to deal with the land tenure question. The Irish Land Act of 1870 gave some security to Irish tenant farmers by preventing arbitrary eviction and giving the tenants financial rights to improvements they made. The agricultural depression of the 1870s soured the mood, and Charles Stewart Parnell set up the Irish Land League that used boycotts and violence against the landlords. Gladstone's Land Act of 1881, called the “Magna Carta” of the Irish farmer, recognized the three F’s (fair rent, fixity of tenure, and freedom of sale) and provided a land commission to determine what was a "fair rent." The Ashbourne Act of 1885 and supplementary acts of 1887 and 1891 provided a loan fund of many millions of pounds for tenants who wished to purchase their lands. Parnell mastered the arts of filibustering and parliamentary obstruction with 86 solid votes from Irish Nationalist MPs in Parliament he controlled. They were elected thanks to Gladstone's Third Reform Bill of 1884, which greatly extended the franchise and for the first time treated Ireland and Great Britain on equal terms, thus tripling the Irish electorate. Parnell's MP's brought down Gladstone's second government in June of 1885; he was replaced by the Conservatives under Lord Salisbury.

Home Rule movement

Most Irish people elected as their MPs Liberals and Conservatives who belonged to the main British political parties (note: the poor didn't have a vote at that time). A significant minority also elected Unionists, who championed the cause of the maintenance of the Act of Union. A former Tory barrister turned nationalist campaigner, Isaac Butt, established a new moderate nationalist movement, the Home Rule League, in the 1870s. After Butt's death the Home Rule Movement, or the Irish Parliamentary Party as it had become known, was turned into a major political force under the guidance of William Shaw and in particular Charles Stewart Parnell. Born into a wealthy and powerful Anglo-Irish Anglican landowning family, he entered the House of Commons in 1875. He was a land reform agitator, and became leader of the Home Rule League in 1880. Parnell operated independently of the Liberals, and won great influence by his balancing of constitutional, radical, and economic issues, and by his skillful use of parliamentary procedure. He was imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol in 1882 but, a very capable negotiator, was released when he renounced violent extra-Parliamentary action. That same year he reformed the Home Rule League as the Irish Parliamentary Party, which he controlled minutely as either Ireland's or Britain's first disciplined democratic party. The Irish Parliamentary Party dominated Irish politics, to the exclusion of the previous Liberal, Conservative and Unionist parties that had existed. Parnell's movement proved to be a broad church, from conservative landowners to the Land League which was campaigning for fundamental reform of Irish landholding, where most farms were held on rental from large aristocratic estates.[13]

Parnell's movement campaigned for 'Home Rule', by which Ireland would govern itself in domestic affairs inside the United Kingdom, in contrast to O'Connell who wanted complete independence subject to a shared monarch and Crown. Two Home Rule Bills (1886 and 1893) were introduced by Liberal Prime Minister Ewart Gladstone, but neither became law, mainly due to opposition from the House of Lords. The issue divided Ireland, for a significant unionist minority (largely based in Ulster), opposed Home Rule, fearing that a Catholic-Nationalist parliament in Dublin meant rule by Rome and a degradation of Protestantism. It also meant economic stagnation as the Catholic peasants would discriminate against businessmen and would impose tariffs on industry, which was located mostly in Ulster. Joseph Hocking, for example, warned that history teaches that, "Rome Rule means corruption, decadence, and ruin."[14]

1900 to 1922

Land reform

A central issue throughout the 19th and early 20th century was highly unequal land ownership. A small group of about 10,000 rich English Protestant families owned practically all the farmland in Ireland. Most were absentee landlords: they were permanent residents of England, where they had a powerful political voice. They seldom visited the land; they rented it out to Irish tenant farmers. Falling behind in rent payments meant eviction, and very bad feelings.[15] The land proposals in Gladstone's Government of Ireland Bill 1886 was an unexpected shock to his supporters and brought down his third government in a matter of months. The bill gave all owners of Irish land a chance to sell to the state at a price equal to 20 years' of the rents and helped tenants to purchase the land. Irish reaction was mixed. The Catholics were supportive but not the Protestant Unionist opinion, English radicals were also against the bill. Among the Liberal rank and file, several Gladstonian candidates disowned the bill, reflecting fears at the constituency level that the interests of the working people were being sacrificed to finance a rescue operation for the landed elite.[16] Meanwhile serious confrontations continued between the local magistrates (who represented the Protestant landowners) and the Irish National League, which told tenants to withhold rents from extortionate landlords.

Several organized movements made land reform their central issue. The Land League under Charles Stewart Parnell and Michael Davitt demanding the 3 Fs: Fair rent, free sale, fixity of tenure. The rates had to be reasonable, the tenant could sell his tenancy to another tenant, and he could not be easily removed. The period of the Land League's agitation is known as the Land War. The Land League's long-term goal was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmers to own the land they worked on. League protests sometimes involved violent attacks on the landowners properties, and occasional violence against them. A highly successful technique was the boycott]] – any Irishman who rented the farm following an eviction was boycotted – no Irishman would talk to him, work for him, buy from him or sell him anything. It was deployed first in County Mayo in 1880 by the Land League.[17] Historian R. F. Foster argues that across the countryside the League "reinforced the politicization of rural Catholic nationalist Ireland, partly by defining that identity against urbanization, landlordism, Englishness and—implicitly—Protestantism."[18] Foster adds that about a third of the activists were Catholic priests, and Archbishop Thomas Croke was one of its most influential champions.[19]

As a result of the Land War agitations and subsequent Plan of Campaign of the 1880s, various British governments introduced a series of Irish Land Acts. Liberal Prime Minister Gladstone took the lead and made the 3 F's the basis of a new law in 1870. Parliament passed additional laws that lowered rents and enabled the tenant farmers to purchase their lands.[20] The issue was finally settled by the Conservatives under Arthur Balfour. William O'Brien played a leading role in the 1902 Land Conference to pave the way for the most advanced social legislation in Irish history, the Wyndham Land Purchase Act of 1903. The British government allocated increasing sums--up to £120 million. When a tenant wanted to buy his farm, the government bought it from the landlord, usually at a very high price, and sold it much cheaper on easy terms to the tenant. By 1914, most of the land was now owned by former tenants. English landholders, who for centuries had been the foundation of the Protestant Ascendancy, took the money, returned to England, and forgot about Ireland. It effectively ended the era of the absentee landlord, finally resolving the Irish Land Question. [21] Historian R.K. Webb gives most of the credit for the Wyndham act to Conservative leader Arthur Balfour. He says the act was:

- A complete success. By the time the Irish Free State was created in 1922, the system of peasant proprietorship had become universal.... A land problem more than a century old had been solved, though it had taken more than 30 years of educating Parliament and landlords to do it. The scheme was intended as well to "kill Home Rule by kindness".[22]

Passage of Home Rule, 1910-14

As a minority party after 1910 elections, the Liberals depended on the Irish vote, controlled by John Redmond. To gain Irish support for the budget and the parliament bill, Asquith promised Redmond that Irish Home Rule would be the highest priority.[23] It proved much more complex and time-consuming than expected.[24] Support for self-government for Ireland had been a tenet of the Liberal Party since 1886, but Asquith had not been as enthusiastic, stating in 1903 (while in opposition) that the party should never take office if that government would be dependent for survival on the support of the Irish Nationalist Party.[25] After 1910, though, Irish Nationalist votes were essential to stay in power. Retaining Ireland in the Union was the declared intent of all parties, and the Nationalists, as part of the majority that kept Asquith in office, were entitled to seek enactment of their plans for Home Rule, and to expect Liberal and Labour support. The Conservatives, with die-hard support from the Protestant Orangemen of Ulster, were strongly opposed to Home Rule. The desire to retain a veto for the Lords on such bills had been an unbridgeable gap between the parties in the constitutional talks prior to the second 1910 election.[26] The cabinet committee (not including Asquith) that in 1911 planned the Third Home Rule Bill opposed any special status for Protestant Ulster within majority-Catholic Ireland. Asquith later (in 1913) wrote to Churchill, stating that the Prime Minister had always believed and stated that the price of Home Rule should be a special status for Ulster. In spite of this, the bill as introduced in April 1912 contained no such provision, and was meant to apply to all Ireland. Neither partition nor a special status for Ulster was likely to satisfy either side.[27] The self-government offered by the bill was very limited, but Irish Nationalists, expecting Home Rule to come by gradual parliamentary steps, favoured it. The Conservatives and Irish Unionists opposed it. Unionists began preparing to get their way by force if necessary, prompting nationalist emulation. The Unionists were in general better financed and more organised.[28] In April 1914 the Ulster Volunteers smuggled in 25,000 rifles and bayonets and over 3 million rounds of ammunition purchased from Germany.[29]

Since the Parliament Act the Unionists could no longer block Home Rule in the House of Lords, but only delay Royal Assent by two years. Asquith decided to postpone any concessions to the Unionists until the bill's third passage through the Commons, when he believed the Unionists would be desperate for a compromise.[30] Historian Roy Jenkins concluded that had Asquith tried for an earlier agreement, he would have had no luck, as many of his opponents wanted a fight and the opportunity to smash his government.[31] Edward Carson, leader of the Irish Unionists in Parliament, threatened a revolt if Home Rule was enacted.[32] The new Conservative leader, Bonar Law, campaigned in Parliament and in northern Ireland, warning Ulstermen against "Rome Rule", that is, domination by the island's Catholic majority.[33] Many who opposed Home Rule felt that the Liberals had violated the Constitution—by pushing through major constitutional change without a clear electoral mandate, with the House of Lords, formerly the "watchdog of the constitution", not reformed as had been promised in the preamble of the 1911 Act—and thus justified actions that in other circumstances might be treason.[34] Bonar Law was pushing hard--certainly blustering and threatening, and perhaps bluffing--but in the end his strategy proved both coherent and effective.[35]

The passions generated by the Irish question contrasted with Asquith's cool detachment, and he wrote about the prospective partition of the county of Tyrone, which had a mixed population, deeming it "an impasse, with unspeakable consequences, upon a matter which to English eyes seems inconceivably small, & to Irish eyes immeasurably big".[36] As the Commons debated the Home Rule bill in late 1912 and early 1913, unionists in the north of Ireland mobilised, with talk of Carson declaring a Provisional Government and Ulster Volunteer Forces (UVF) built around the Orange Lodges, but in the cabinet, only Churchill viewed this with alarm.[37] These forces, insisting on their loyalty to the British Crown but increasingly well-armed with smuggled German weapons, prepared to do battle with the British Army, but Unionist leaders were confident that the army would not aid in forcing Home Rule on Ulster. As the Home Rule bill awaited its third passage through the Commons, the Curragh incident occurred in April 1914. Some sixty army officers, led by Brigadier-General Hubert Gough, announced that they would rather be dismissed from the service than obey.[38] With unrest spreading to army officers in England, the Cabinet acted to placate the officers with a statement written by Asquith reiterating the duty of officers to obey lawful orders but claiming that the incident had been a misunderstanding. War minister John Seely then added an unauthorised assurance, countersigned by General John French (the head of the army), that the government had no intention of using force against Ulster. Asquith repudiated the addition, and required Seely and French to resign. Asquith took control of the War Office himself, retaining the additional responsibility until the war began in 1914.[39][40]

On 12 May, Asquith announced that he would secure Home Rule's third passage through the Commons (accomplished on 25 May), but that there would be an amending bill with it, making special provision for Ulster. However the Lords made changes to the amending bill unacceptable to Asquith, and with no way to invoke the Parliament Act on the amending bill, Asquith agreed to meet other leaders at an all-party conference on 21 July at Buckingham Palace, chaired by the King. When no solution could be found, Asquith and his cabinet planned further concessions to the Unionists, but this was suspended when the crisis on the Continent erupted into war. In September 1914, the Home Rule bill went on the statute book (as the Government of Ireland Act 1914) but was immediately suspended. It never went into effect.[41]

World War, Partition of Ireland and Irish Independence

The Liberal government of Herbert Asquith had put the Government of Ireland Act 1914 through Parliament. Militant opposition from the Unionists in Ulster loyal to the king threatened violent resistance--they had stockpiled weapons and had considerable support from the British Army. Asquith , proposed a temporary pause before Ulster would be incorporated into the proposed Irish state. On the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 he it had agreed with Redmond, the leader of the IPP, that the Home Rule Bill would be signed into law, accompanied by an Act suspending it for the duration of the war. This was done. This solution was supported at the time by a majority of the Irish population, and large numbers of Irish men volunteered for the British Army; the Conscription Act of 1915 did not apply to Ireland. During these two years the threat of civil war hung over Ireland with the creation of the Unionist Ulster Volunteers opposed to the Act and their nationalist counterparts, the Irish Volunteers supporting the Act. These two groups armed themselves by importing rifles and ammunition and carried out drills openly. Ireland was at war with Germany and most Unionist and Nationalist volunteer forces freelu enlisted in the new British Service Army. Republican journals openly advocated violence, denounced recruiting, and vigorously promoted the views of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). When one paper was suppressed, another took its place. Gunrunning was organized, paid for by multimillion-dollar fundraising in the United States. The IRB asked the Kaiser to include freedom of Ireland as a German war aim. Germany promised to send 20,000 rifles and machine guns, ammunition, and explosives in the custody of Sir Roger Casement. London knew trouble was brewing but decided to be extremely cautious, fearing that a full-scale clampdown on the IRB would have highly negative repercussions in the United States, which remained neutral in the war until April 1917. Instead, London made the wrongheaded decision to rely on the loyalty of Redmond and the well-established Irish Parliamentary party.[42]

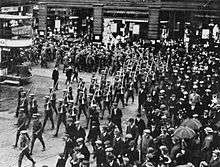

Easter Rising

A unilaterally declared "Irish Republic" was proclaimed in Dublin during Time Easter week in 1916 --the Easter Rising. British attention was focused on the Western Front, where the Allied armies were not doing well. The uprising was very poorly organized and led, and was crushed after six days of fighting. The death total was 134 British soldiers, and 285 rebels; when they surrendered, Dubliners bood them In the newspapers called their venturer a foolish, futile, cruel and mad act. A year later, however, they became – and remained to this day – he rose of the Irish independence movement. That been given quick trials, and quick executions, but they died like martyrs imitating Christ's crucifixion. Most of its leaders were court-martialed and swiftly executed. Historians Clayton Roberts and David Roberts argue:

- the theme of redemption in the absence of socialist dogmas allowed the Catholic hierarchy and its worshipers to see these men as heroically devoted to Ireland.... Militarily the rebellion was foolish, futile, and bungled; theatrically it was brilliant and moving, a tragic act of singular dramatic power. It released the nationalist feeling that forms one of the most powerful forces in modern history. [43]

Very large numbers of Catholics across Ireland now deserted the IPP and joined the Sinn Féin, the extreme nationalist cause demanding immediate independence.[44] In 1917 coalition Prime Minister David Lloyd George tried to introduce Home Rule at the close of the 1917-18 Irish Convention. He failed because he also was desperate for soldiers and imposed conscription on Ireland. As a result in the December 1918 General Election Sinn Féin won a majority of Irish seats, its MPs refusing to take their seats at Westminster. Instead they set up their own First Dáil parliament in Dublin, but it had no money or power. A declaration of independence was ratified by Dáil Éireann, the self-declared Republic's parliament in January 1919. Guerrilla warfare broke out against the British government, which was still in control in Ireland. Coalition government in London had three choices: implement the 1914 Home Rule Act with an amending bill to exclude Ulster; repeal it; or replace it with new legislation. It took the third route. The Government of Ireland Act 1920 partitioned Ireland, North and South. The policy had broad support in Northern Ireland, as well as England Wales and Scotland, with support from Conservatives and Liberals, although the small new Labour Party opposed partition. Rejection came from Catholic Ireland-- the South, leading to war.[45]

Anglo-Irish war

The Irish War of Independence or Anglo-Irish War or the "Black and Tan War" was fought between the forces of the provisional government of the Irish Republic and Britain, January 1919 and July 1921. The war began with an ambush of two Royal Irish Constabulary men, which was endorsed by the shadow government, the First Dáil. The British tried repressive force but the IRA under Michael Collins used about 3,000 fighters in a guerrilla war, After 10,000 deaths a truce was called in 1922. The treaty of December 1922 split off Ulster, and created an independent Free State in the south.[46]

Irish Free State

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921, was ratified by three parliaments. It ended the Anglo-Irish War, established the Irish Free State. It was initially a British Empire Dominion in the same vein as Canada or South Africa. The moribund declared Irish Republic then triggered an Irish Civil War. The Irish Free State subsequently left the British Commonwealth and became the Republic of Ireland after World War II, without constitutional ties with the United Kingdom. Six northern, predominantly Protestant, Irish counties remained part of the United Kingdom as (Northern Ireland, with its own parliament and home rule. Controversial aspects of the treaty were partition, that Ireland should be a member of the Commonwealth, and some of its elected representatives should swear an oath of allegiance to the king as head of the Commonwealth. The Irish split, with a majority under Michael Collins (1890-1922) in favour and a minority under Éamon de Valera (1882-1975) opposed. They fought a civil war, and the majority faction won. That state is now known as the Republic of Ireland.[47]

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland continued in name until 1927 when it was renamed as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Despite increasing political independence from each other from 1922, and complete political independence since 1949, the union left the two countries intertwined with each other in many respects.

The Government of Northern Ireland from 1921 was fashioned by such Protestant leaders as Sir Edward Carson and Sir James Craig. It presided over social, cultural, political and economic discrimination against the Catholic minority. Northern Ireland became, in the words ofg David Trimble, a "cold place for Catholics." After four decades of "The Troubles", peace finally was achieved with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.[48]

See also

- All-for-Ireland League, 1906-1918

- Cork Free Press 1910 – 16

- History of Ireland (1801-1923)

- History of Northern Ireland

- Home Rule Act 1914

- Ireland and World War I

- Irish Convention

- Irish Home Rule movement, 1870-1921

- Irish Land Acts, 1870-1901

- Irish Land and Labour Association, 1890s

- Irish Parliamentary Party, IPP, 1874-1918

- Irish Reform Association, `1904-5

- Irish Republican Army

- Irish nationalism

- Land Conference, 1902

- Michael Davitt, 1846-1906

- National Volunteers

- No Rent Manifesto , 1881

- Plan of Campaign, 1886-91

- Unionism in Ireland

- United Irish League, 18986-1920s

Notes

- ↑ A short summary see Nick Pelling, Anglo-Irish Relations, 1798-1922 (2003)

- ↑ G. M. Ditchfield, "Ecclesiastical Legislation During the Ministry of the Younger Pitt, 1783–1801." Parliamentary History 19.1 (2000): 64-80.

- ↑ R. B. McDowell, Ireland in the Age of Imperialism and Revolution, 1760-1801 (1991) pp 595-651, 682-87.

- ↑ Michael J. Winstanley, Ireland and the Land Question 1800-1922 (1986) p 2

- ↑ Christine Kinealy, This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845-52, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1994. ISBN 0-7171-1832-0 p354

- ↑ Cecil Woodham-Smith, The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845–1849 (1962), p 31

- ↑ Nick Pelling, Anglo-Irish Relations, 1798-1922 (2003) pp 41-58

- ↑ O'Leary, Philip. The Prose Literature of the Gaelic Revival, 1881–1921: Ideology and Innovation. Penn State Press, 1994.

- ↑ by Thomas E. Hachey and Lawrence J. McCaffrey, The Irish Experience Since 1800: A Concise History (2010) pp 86-88.

- ↑ Allen Warren, "Disraeli, the Conservatives and the National Church, 1837–1881." Parliamentary History 19.1 (2000): 96-117. online

- ↑ Robert Blake, Disraeli (1967), pp. 496–499.

- ↑ Nick Pelling, Anglo-Irish Relations, 1798-1922 (2003) pp 59-78

- ↑ Francis S.L. Lyons,"The Political Ideas of Parnell." Historical Journal 16.4 (1973): 749-775. online

- ↑ Joseph Hocking, Is Home rule Rome rule? (London, 1912) p 8.online

- ↑ Michael J. Winstanley, Ireland and the Land Question 1800-1922 (1984) online

- ↑ Graham D. Goodlad, "The Liberal Party and Gladstone's Land Purchase Bill of 1886." Historical Journal 1989 32(3): 627-641. in Jstor

- ↑ Joyce Marlow, Captain Boycott and the Irish (1973).

- ↑ R.F. Foster, Modern Ireland, 1600-1972 (1988) p 415.

- ↑ Foster, Modern Ireland, 1600-1972 (1988) p 417-18.

- ↑ Timothy W. Guinnane and Ronald I. Miller. "The Limits to Land Reform: The Land Acts in Ireland, 1870–1909" Economic Development and Cultural Change 45#3 (1997): 591-612. online

- ↑ Fergus Campbell and Tony Varley, eds. Land Questions in Modern Ireland (2013) excerpt

- ↑ R.K. Webb, Modern England from the Eighteenth Century to the Present (1968) p 430.

- ↑ George Dangerfield, The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935) p 74-76.

- ↑ Robert Pearce and Graham Goodlad, British Prime Ministers from Balfour to Brown (2013) p 30.

- ↑ Roy Hattersley, The Edwardians (2005) pp 184-85.

- ↑ Roy Jenkins, Asquith (1964) p 215.

- ↑ R. C. K. Ensor, England, 1870-1914 (1936) pp. 472-81.

- ↑ Hattersley, The Edwardians (2005) pp 215-18.

- ↑ Timothy Bowman, Carson's Army: The Ulster Volunteer Force, 1910--22 (Manchester UP, 2007).

- ↑ Pearce and Goodlad, British Prime Ministers from Balfour to Brown (2013) pp 30-31.

- ↑ Jenkins, Asquith (1964) p 281.

- ↑ Richard Killeen (2007). A Short History of the Irish Revolution, 1912 to 1927: From the Ulster Crisis to the formation of the Irish Free State. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Piers Brendon (2010). The Decline and Fall of the British Empire, 1781-1997. p. 304.

- ↑ Hattersley, The Edwardians (2005) p 190.

- ↑ Jeremy Smith, “Bluff, Bluster and Brinkmanship: Andrew Bonar Law and the Third Home Rule Bill.” Historical Journal 36#1 (1993): 161-178.

- ↑ Pearce and Goodlad, British Prime Ministers from Balfour to Brown (2013) p 31.

- ↑ Hattersley, The Edwardians (2005) pp 192-93.

- ↑ Dangerfield, The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935) pp 343-50.

- ↑ Jenkins, Asquith (1964) pp 311-13.

- ↑ Benjamin Grob-Fitzgibbon, "Neglected Intelligence: How the British Government Failed to Quell the Ulster Volunteer Force, 1912–1914." Journal of Intelligence History 6.1 (2006): 1-23.

- ↑ Desmond Keenan (2008). Ireland Within the Union 1800-1921. p. 208.

- ↑ W.N. Medlicott, Contemporary England 1914-1964 (1967) pp 38-39.

- ↑ Clayton Roberts and David Roberts, A History of England: 1688 to the Present (3rd ed. 1991) pp 742-43..

- ↑ Erica Doherty, "‘The Party Hack, and Tool of the British Government’: T. P. O'Connor, America and Irish Party Resilience at the February 1918 South Armagh By‐Election." Parliamentary History 34.3 (2015): 339-364.

- ↑ Ivan Gibbons, "The British Parliamentary Labour Party and the Government of Ireland Act 1920." Parliamentary History 32.3 (2013): 506-521

- ↑ Michael Hopkinson, The Irish war of independence (McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP, 2002).

- ↑ Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins (1990)

- ↑ Marc Mulholland, Northern Ireland: A Very Short Introduction (2003)

Further reading

- Akenson, Donald H. The Irish Education Experiment: The National System of Education in the Nineteenth Century (1981; 2nd ed 2014)

- Asch, R.G. ed. Three Nations: A Common History? England, Scotland, Ireland and British History c.1600–1920 (1993)

- Beales, Derek. From Castlereagh to Gladstone, 1815–1885 (1969), survey of political history online

- Bew, Paul. "Parnell, Charles Stewart (1846–1891)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press, 2004)

- Bew, Paul. Enigma: A New Life of Charles Stewart Parnell (Gill & Macmillan, 2011) excerpt

- Boyce, D. George and Alan O'Day, eds. Gladstone and Ireland: Politics, Religion, and Nationality in the Victorian Age (Palgrave Macmillan; 2011), 307 pp.

- Boyce, D. G. The Irish Question and British Politics, 1868-1996 (1996).

- Bright, J. Franck. A History Of England. Period 4: Growth Of Democracy: Victoria 1837–1880 (1893)online 608pp; highly detailed political narrative

- Bright, J. Franck. A History of England: Period V. Imperial Reaction: Victoria 1880–1901 (vol 5, 1904); detailed political narrative; 295pp; online; also another copy

- Cannon, John, ed. The Oxford Companion to British History (2003), historical encyclopedia; 4000 entries in 1046pp excerpt and text search

- Connolly, S.J. ed. Kingdoms United? Great Britain and Ireland since 1500 (1999)

- Curtis, Lewis Perry. Coercion and Conciliation in Ireland 1880-1892 (Princeton UP, 2015).

- Dangerfield, George. The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935) online free; Classic account of how the Liberal Party ruined itself in dealing with the House of Lords, woman suffrage, the Irish question, and labour unions, 1906-1914.

- Dooley, Chris. Redmond–A Life Undone: The Definitive Biography of John Redmond, the Forgotten Hero of Irish Politics (Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 2015).

- Ensor, R. C. K. England, 1870–1914 (1936) online, passim. influential scholarly survey

- Flewelling, Lindsey. "The Ulster Crisis in Transnational Perspective: Ulster Unionism and America, 1912–14" Éire-Ireland 51#1 (2016) pp. 118-140 excerpt

- Foster, R. F. Vivid Faces: The Revolutionary Generation in Ireland, 1890–1923 (2015) excerpt

- Golden, J. J. "The Protestant Influence on the Origins of Irish Home Rule, 1861–1871." English Historical Review 128.535 (2013): 1483-1516.

- Havighurst, Alfred F. Modern England, 1901–1984 (2nd ed. 1987) online

- Hachey, Thomas E., and Lawrence J. McCaffrey. The Irish Experience Since 1800: A Concise History 3rd ed. 2010).

- Hickey, D. J., J. E. Doherty. eds. A New Dictionary of Irish History from 1800, Gill & Macmillan, 2003, ISBN 978-0-7171-2520-3

- Hilton, Boyd. A Mad, Bad, and Dangerous People?: England 1783–1846 (New Oxford History of England) (2008), scholarly synthesis excerpt and text search

- Hoppen, Theodore. The Mid-Victorian Generation 1846–1886 (New Oxford History of England) (2000) excerpt and text search

- Jalland, Patricia. The Liberals and Ireland: the Ulster question in British politics to 1914 (Harvester Press, 1980).

- Kee, Robert. The Green Flag, (Penguin, 1972) popular history of Irish nationalism

- Hammond, J. L. Gladstone and the Irish nation (1938) online edition.

- Loughlin, J. Gladstone, home rule and the Ulster question, 1882–1893 (1986). online

- McCord, Norman and Bill Purdue. British History, 1815–1914 (2nd ed. 2007), 612 pp online, university textbook

- Lyons, F. S. L.. Charles Stewart Parnell (1973)

- Magnus, Philip M. Gladstone: A biography (1954) online

- Matthew, H. C. G. "Gladstone, William Ewart (1809–1898)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004; online edition, May 2006.

- Mowat, Charles. Britain Between The Wars 1918-1940 (1968)

- Pearce, Malcolm, and Geoffrey Stewart. British political history, 1867–2001: democracy and decline (Routledge, 2013).

- Pelling, Nick. Anglo-Irish Relations: 1798–1922 (Routledge, 2005).

- Searle, G. R. A New England?: Peace and War 1886–1918 (New Oxford History of England) (2005) excerpt and text search

- Smith, Jeremy. Britain and Ireland: from home rule to independence (Routledge, 2014).

- Smith, Jeremy. The Tories and Ireland 1910-1914: Conservative Party Politics and the Home Rule Crisis (2001)

- Townshend, Charles. The British campaign in Ireland, 1919-1921: the development of political and military policies (Oxford UP, 1975).

- Vincent, J. Gladstone and Ireland (1978).

- Warren, Allen. "Disraeli, the Conservatives, and the government of Ireland: part 1, 1837–1868." Parliamentary History 18.1 (1999): 45-64.

- Woodward, Llewellyn. The Age of Reform, 1815-1870 (2nd ed. 1962) pp 328-65. brief scholarly overview online

Historiography

- Connolly, S. J. ed. Oxford Companion to Irish History (2002), 650pp

- English, Richard. "Directions in historiography: history and Irish nationalism." Irish Historical Studies 37.147 (2011): 447-460.

- Gkotzaridis, Evi. Trials of Irish History: Genesis and Evolution of a Reappraisal (2006)

- Kenealy, Christine. "Politics in Ireland in Chris Williams, ed., A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain (2006) pp 473-89.

- Raftery, Deirdre, Jane McDermid, and Gareth Elwyn Jones. "Social Change and Education in Ireland, Scotland and Wales: Historiography on Nineteenth‐century Schooling." History of Education 36.4-5 (2007): 447-463.