Python molurus

| Python molurus | |

|---|---|

| Near Nagarhole National Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Pythonidae |

| Genus: | Python |

| Species: | P. molurus |

| Binomial name | |

| Python molurus | |

| |

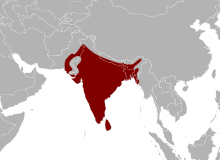

| Distribution of Indian python | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Python molurus is a large nonvenomous python species found in many tropical and subtropical areas of the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It is known by the common names Indian python,[2] black-tailed python,[3] and Indian rock python. The species is limited to Southern Asia. It is generally lighter colored than the Burmese python and reaches usually 3 m (9.8 ft).[4]

Common names

Common names include Indian python,[2] black-tailed python,[3] Indian rock python, and Asian rock python.[5][6] In other languages, it is commonly referred to as ajingar in Nepali,ajgar in Hindi and Marathi,ଅଜଗର (ajagara) in Odia, azdaha in Urdu, অজগর (awjogor), মেঘডম্বুর (meghdombur) and মেগডুম (megdum) in Bengali, hebbaavu (ಹೆಬ್ಬಾವು) in Kannada, kondachiluva (కొండచిలువ) in Telugu, malai paambu (மலைப் பாம்பு) in Tamil and malampaambu (മലമ്പാമ്പ്) in Malayalam. The subspecies Python molurus pimbura was thought to have stemmed from the alias given in Sri Lanka, but the pimbura, or Ceylonese python, is no longer considered a valid subspecies.

Description

The color pattern is whitish or yellowish with the blotched patterns varying from shades of tan to dark brown. This varies with terrain and habitat. Specimens from the hill forests of Western Ghats and Assam are darker, while those from the Deccan Plateau and East Coast are usually lighter.[7]

In India, the nominate subspecies grows to 3 m (9.8 ft) typically.[4][7] This value is supported by a 1990 study in Keoladeo National Park, where the biggest 25% of the python population was 2.7–3.3 m (8.9–10.8 ft) long. Only two specimens even measured nearly 3.6 m (12 ft).[8] Because of confusion with the Burmese python, exaggerations and stretched skins in the past, the maximum length of this subspecies is hard to tell. The longest scientifically recorded specimen, which hailed from Pakistan, was 4.6 m (15 ft) in length and weighed 52 kg (110 lb).[9] In Pakistan, Indian pythons commonly reach a length of 2.4–3.0 m (7.9–9.8 ft).[9]

Distribution and habitat

The nominate subspecies is found in India, southern Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and probably in the north of Myanmar.[10] They occur in a wide range of habitats, including grasslands, swamps, marshes, rocky foothills, woodlands, "open" jungle, and river valleys. They depend on a permanent source of water.[11] Sometimes, they can be found in abandoned mammal burrows, hollow trees, dense water reeds, and mangrove thickets.[7]

Behavior

Lethargic and slow moving even in their native habitat, they exhibit timidity and rarely try to attack even when attacked. Locomotion is usually with the body moving in a straight line. They are excellent swimmers and are quite at home in water. They can be wholly submerged in water for many minutes if necessary, but usually prefer to remain near the bank.

Feeding

Like all snakes, Indian pythons are strict carnivores and feed on mammals, birds, and reptiles indiscriminately, but seem to prefer mammals. Roused to activity on sighting prey, the snake advances with a quivering tail and lunges with an open mouth. Live prey is constricted and killed. One or two coils are used to hold it in a tight grip. The prey, unable to breathe, succumbs and is subsequently swallowed head first. After a heavy meal, they are disinclined to move. If forced to, hard parts of the meal may tear through the body. Therefore, if disturbed, some specimens disgorge their meal to escape from potential predators. After a heavy meal, an individual may fast for weeks, the longest recorded duration being 2 years. The python can swallow prey bigger than its diameter because the jaw bones are not connected. Moreover, prey cannot escape from its mouth because of the arrangement of the teeth (which are reverse saw-like).

Reproduction

Oviparous, up to 100 eggs are laid by the animal, which are protected and incubated by the female.[11] Towards this end, they are capable of raising their body temperature above the ambient level through muscular contractions.[12] The hatchlings are 45–60 cm (18–24 in) in length and grow quickly.[11] An artificial incubation method using climate-controlled environmental chambers was developed in India for successfully raising hatchlings from abandoned or unattended eggs.[13]

Conservation status

The Indian python is classified as lower risk/near threatened on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (v2.3, 1996).[14] This listing indicates that it may become threatened with extinction and is in need of frequent reassessment.[15]

Taxonomy

In the literature, one other subspecies may be encountered: P. m. pimbura Deraniyagala, 1945, which is found in Sri Lanka.

The Burmese python (Python bivittatus) was referred to as a subspecies of the Indian python until 2009, when it was elevated to full species status.[16] The name Python molurus bivittatus is found in older literature.

In culture

Kaa, a large and elderly Indian python, is featured in The Jungle Book.

See also

- List of pythonid species and subspecies.

- Pythonidae by common name.

- Pythonidae by taxonomic synonyms.

References

- ↑ McDiarmid RW, Campbell JA, Touré T. 1999. Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, vol. 1. Herpetologists' League. 511 pp. ISBN 1-893777-00-6 (series). ISBN 1-893777-01-4 (volume).

- 1 2 "Python molurus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- 1 2 Ditmars RL. 1933. Reptiles of the World. Revised Edition. The MacMillan Company. 329 pp. 89 plates.

- 1 2 Wall, F. (1912), "A popular treatise on the common Indian snakes – The Indian Python", Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 21: 447–476 .

- ↑ Jerry G. Walls: "The Living Pythons";T. F. H. Publications, 1998: pp. 131-142; ISBN 0-7938-0467-1

- ↑ Mark O’Shea: „Boas and Pythons of the World“; New Holland Publishers, 2007; pp 80-87; ISBN 978-1-84537-544-7

- 1 2 3 Rhomulus Whitaker: „Common Indian Snakes – A Field Guide“; The Macmillan Company of India Limited, 1987; pp. 6-9; SBN 33390-198-3

- ↑ Bhupathy, S. (1990), "Blotch structure in individual identification of the Indian Python (Python molurus molurus) and its possible usage in population estimation", Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 87 (3): 399–404 .

- 1 2 Minton, S. A. (1966), "A contribution to the herpetology of West Pakistan", Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 134 (2): 117–118 .

- ↑ R. Whitaker, A. Captain: Snakes of India, The field guide. Chennai, India: Draco Books 2004, ISBN 81-901873-0-9, p. 3, 12, 78-81.

- 1 2 3 Mehrtens JM. 1987. Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. ISBN 0-8069-6460-X.

- ↑ Hutchison, Victor H.; Dowling, Herndon G. & Vinegar, Allen (1966), "Thermoregulation in a Brooding Female Indian Python, Python molurus bivittatus", Science, 151 (3711): 694–695, doi:10.1126/science.151.3711.694 .

- ↑ Balakrishnan, Peroth; Sajeev, T.V; Bindu, T.N (2010). "Artificial incubation, hatching and release of the Indian Rock Python Python molurus (Linnaeus, 1758), in Nilambur, Kerala" (PDF). Reptile Rap. 10: 24–27.

- ↑ Python molurus at the IUCN Red List. Accessed 12 July 2009.

- ↑ 1994 Categories & Criteria (version 2.3) at the IUCN Red List. Accessed 13 September 2007.

- ↑ Jacobs, H.J.; Auliya, M.; Böhme, W. (2009). "On the taxonomy of the Burmese Python, Python molurus bivittatus KUHL, 1820, specifically on the Sulawesi population". Sauria. 31 (3): 5–11.

Further reading

- Whitaker R. (1978). Common Indian Snakes: A Field Guide. Macmillan India Limited.

- Daniel, JC. The Book Of Indian Snakes and Reptiles. Bombay Natural History Society

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Python molurus. |

- Python molurus at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 13 September 2007.

- Indian Python at Ecology Asia. Accessed 13 September 2007.

- Indian python at Animal Pictures Archive. Accessed 13 September 2007.

- Watch Indian rock python (Python molurus) video clips from the BBC archive on Wildlife Finder