Ian Hornak

| Ian Hornak | |

|---|---|

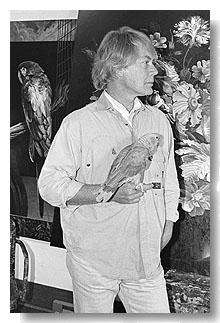

Hornak in his East Hampton, New York studio, 1997 | |

| Born |

John Francis Hornak January 9, 1944 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Died |

December 9, 2002 (aged 58) Southampton, New York |

| Nationality | American (United States) |

| Education | University of Michigan, Wayne State University |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, printmaking |

| Movement | Hyperrealism, Photorealism |

| Website |

www |

Ian Hornak (January 9, 1944 – December 9, 2002) was an American draughtsman, painter and printmaker and one of the founding artists of the Hyperrealist and Photorealism art movements.[1][2]

Biography

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to parents who immigrated from Slovakia, Hornak moved to Brooklyn, New York at the age of 3 and then relocated with his family to Mount Clemens, Michigan at age 8.[1][3] At age 9 he received a set of oil paints and a book of important Renaissance paintings from his mother as a gift and immediately began copying the works of Michelangelo Buonarroti, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael Sanzio.[1][3] During an interview with the 57th Street Review in 1976, Hornak remarked "I picked up my technique as a child through my interest in art and copying paintings I liked. I especially loved Renaissance painting, because it had clarity and simplification of form and great organization".[4] Upon graduating from High School in New Haven, Hornak relocated to Detroit and attended the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and later received his BFA and MFA at Wayne State University where he taught for a short time.[1][3]

Hornak produced Hyperrealist and Photorealism artwork with surreal overtones in the midst of the pop art movement.[1] He was introduced into the New York City art scene in 1968 by Pop Artist, Lowell Blair Nesbitt, with whom Hornak lived and worked until 1969.[1][3] By 1971, he maintained his primary residence and studio in East Hampton, NY where he lived until his death in 2002, and a secondary penthouse studio in New York City at 116 East 73rd Street near the corner of Park Avenue.[1] While living in East Hampton, Hornak came to work with and befriend art world figures, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, Robert Indiana, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg and Fairfield Porter.[3]

Artwork

When Hornak began his career in New York in 1968 he created artworks that were pen & ink drawings and paintings of floating figures both clothed and nude, in addition to an erotic art series.[1] In 1970, Hornak began to produce conceptual multiple exposure landscape paintings as well as traditional landscape paintings.[1][3] In 1974 John Canaday wrote in the New York Times, "Mr. Hornak is right at the top of the list of romantically descriptive painters today".[5] As Hornak was nearing the end of the landscape series, Art Critic, Marcia Corbino wrote, *"Not since the Hudson River School glorified the grandiose panorama of the natural world in meticulous detail has an American artist embraced landscape painting with the artistic totality of Ian Hornak".[6] From 1985 until 2002 he produced Dutch & Flemish-inspired botanical and still life paintings with 4-6 inch painted frames, where the artist extended the imagery of the primary painting onto the frame itself.[1][3] Hornak said of the development and creation of those paintings, "I begin with one flower, then add and subtract, balance and counterbalance. The finesse of the surface, the sensual appeal of the subject matter are there but the beauty lies deeper in the content. My flower pieces derive less from 19th century realists and/or impressionists, with their literal depiction of color, texture and form, and more from the 17th century Flemish painters whose flowers give visual pleasure, and imply a more generalized reality and symbolism".[3] Gerrit Henry wrote of these works, "Hornak is a rather self-explanatory if not wholly tautological postmodernism. Perhaps, though, his excesses ring true for the approaching millennium: this is 'end-time' painting that exercises its romantic license to the fullest in its presentation of multiple styles of the last fin de siècle - naturalist, symbolist, allegorical, apocalyptic".[7] Although Hornak's earliest paintings from 1954-1969 were created using a traditional, brush application of oil paint on canvas, from 1970-1996 the artist chose to use acrylic paint before returning to oil from 1996-2002.[1] The artist often cited the Hudson River School artists as major influences, especially Martin Johnson Heade and Frederic Edwin Church in addition to Nineteenth-Century German Romantic Artist, Caspar David Friedrich.[1][3] Additionally the artist commented on his influences, *"What I so like about Poussin and Cézanne is their sense of organization. I like the way in which they develop space and shape in architectural continuity - the rhythm across their paintings. When I paint a landscape, I get the greatest pleasure out of composing it. As I paint, I try to work out a visual sonata form or a fugue, with realistic images".[8]

Hornak said of his own vision, "While I know that the beautiful, the spiritual and the sublime are today suspect, I have begun to stop resisting the constant urge to deny that beauty has a valid right to exist in contemporary art".[9]

Personal life and art collection

Hornak was openly homosexual and his life partner from 1970-1976 was Julius Rosenthal Wolf[10][11] who was a prominent American casting director, producer, theatrical agent,[11] art collector and art dealer.[12][13] During the 1950s and 1960s, Wolf had been the assistant director of Edith Halpert's Downtown Gallery in New York City where he became a champion of American Modernism in the visual arts. Together, Wolf and Hornak lived at their homes in New York City's Upper East Side and at their weekend home in East Hampton, New York where Hornak continued to live until his own death in 2002.[1] Following Wolf's death in 1976, Frank Burton was Hornak's life partner until Burton's death in 1996.[10]

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Wolf dedicated himself to the collection of American Modernist and African American art, which he had developed a professional knowledge of during his time as assistant director of The Downtown Gallery. After entering into a relationship with Ian Hornak, Hornak introduced Wolf to the contemporary art scene in New York City and educated him on the current trends in contemporary art. Together, Wolf and Hornak assembled a formidable collection of artwork and upon Wolf's death in 1976, per Wolf and Hornak's wishes, John G. Heimann, Wolf's estate executor, delivered a bequeath of the 95 artwork collection to the Hood Museum of Art and the Hopkins Center for the Arts at Wolf's alma mater Dartmouth College. Among the artists whose works are in the collection are David Burliuk, Willard Metcalf, Louis Eilshemius, Arthur Dove, John Marin, Philip Evergood, Marc Chagall, Ben Shahn, Pat Steir, José Luis Cuevas, Philomé Obin, Larry Rivers, Paul Jenkins, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Motherwell, Ellsworth Kelly, Leonard Baskin, Robert Indiana, Lee Bontecou, Ad Reinhardt, Jack Youngerman, Stuart Davis, Larry Poons, Lowell Nesbitt, Jacob Lawrence, Marisol, Joe Brainard and Fairfield Porter. The collection also houses a small collection of intimate paintings and drawings by Ian Hornak that Hornak gifted to Wolf including a large portrait of Wolf, titled "Jay Wolf" that Dartmouth College often uses to display Wolf's likeness.[14] The overall collection of artwork which has been dubbed "The Jay Wolf Bequest of Contemporary Art" by the college was exhibited at the Beaumont-May Gallery in The Hopkins Center, Dartmouth College, June 24-August 28, 1977 and is recognized as the most significant bequest of artwork to Dartmouth College during the 1970s.[13][12]

Death and legacy

Hornak suffered an aortic aneurysm on November 17, 2002 while painting in his studio in East Hampton, New York. Though he was immediately rushed to the Southampton Hospital in New York and surgery was performed to repair the aorta, he died on December 9, 2002 as a result of complications from the surgery.[1] He was 58 years old.[1][15][16][17]

On January 21, 2011, Hornak was buried in a private section of the Great Mausoleum in the Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale in California. A traveling retrospective exhibition, Transparent Barricades: Ian Hornak, A Retrospective, co-sponsored by the Ian Hornak Foundation, began traveling to museums throughout the United States in 2011[1][2] and was scheduled to continue through 2016. Hornak's artwork was the subject of a solo exhibition, on display during the 2013 Presidential Inauguration at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in the Eccles Building in Washington D.C. under the sponsorship of the Ben Bernanke Administration.[1]

Museum and public collections

Hornak's personal papers and effects entered into the permanent collection of the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art in 2007. His artwork is owned by the permanent collections of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American Art, the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History, the Library of Congress, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art, the Allen Memorial Art Museum, the Austin Museum of Art, the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, the Canton Museum of Art, the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, the Detroit Historical Museum, the Flint Institute of Arts, the Forest Lawn Museum, Galleria Internazionale, The George Washington University Art Galleries, Guild Hall, the Children's Hospital Boston (Harvard Medical School affiliate), the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender and Reproduction, the Long Island Museum of American Art, History, and Carriages, the National Czech & Slovak Museum & Library, the National Hellenic Museum, the Ringling College of Art and Design, the Rockford Art Museum, the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, the Florida State Capital, St. Mary's University, Texas, The Art Gallery at the University of Maryland, the University of Texas at San Antonio, the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College, the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts and Wayne State University.[1][2] In 2012, an additional portion of Hornak's papers and personal effects entered the permanent collection of Dartmouth College's Rauner Special Collections Library.[1][2]

Sources

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Stephen Bennett Phillips, Eric Ian Hornak Spoutz, "Ian Hornak Transparent Barricades," exhibition catalogue, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Fine Art Program, Washington D.C., 2012

- 1 2 3 4 Joan Adan, Eric Ian Hornak Spoutz, "Transparent Barricades: Ian Hornak, A Retrospective," exhibition catalogue, Forest Lawn Museum, Glendale, California, May 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Laura Litinsky, "Ian Hornak: A Profusion of Color," Florida Design Magazine, Volume 1-2, June-Aug, 2001

- ↑ Norman Lombino, "Interview", The 57th Street Review, January 1976

- ↑ John Canaday, "Ian Hornak," The New York Times, Jan. 12, 1974

- ↑ Marcia Corbino, Sarasota Herald Tribune, March 7, 1980

- ↑ Gerrit Henry, "Ian Hornak," Art in America, July 1994

- ↑ Ian Hornak, exhibition catalogue, Sneed Gallery, Burpee Art Museum, 1976

- ↑ Leslie Ava Shaw, "The Sanity of Absolute Beauty", Cover Magazine, Feb. 1994

- 1 2 Patsy Southgate, "Ian Hornak: Creating An Art Apart," East Hampton Star, Nov. 20, 1997

- 1 2 "Jay Wolf, 47, Producer, Casting Director and Agent," New York Times, June 14, 1976

- 1 2 "Papers of Jay Wolf, Circa 1900 - 2009," Dartmouth College Rauner Special Collections Library

- 1 2 "Downtown Gallery records, 1824-1974, bulk 1926-1969," Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art

- ↑ http://hoodmuseum.dartmouth.edu/objects/p.976.183

- ↑ Ken Johnson, "Ian Hornak, 58, Whose Paintings Were Known for Hyper-Real Look," New York Times, December 30, 2002

- ↑ "Ian Hornak," Washington Post, Jan. 1. 2003

- ↑ "Ian Hornak, 58; Painter Was Known for Photo- Realism Style," Los Angeles Times, Dec. 20, 2002

External links

![]()