Huixtocihuatl

In Aztec mythology, Huixtocihuatl (or Uixtochihuatl, Uixtociuatl) was a fertility goddess who presided over salt and salt water. She was considered to be the older sister of the rain gods, including Tlaloc.[1] Much of the information known about Huixtocihuatl's iconography and the festival associated with her comes from Bernardino de Sahagun's manuscripts. His Florentine Codex explains how Huixtocihuatl became the salt god.[2] It records that Huixtocihuatl angered her younger brothers by mocking them, so they banished her to the salt beds. It was there where she discovered salt and how it was created.

Associations

Some sources describe Huixtocihuatl as a provider god along with Chicomecoatl and Chalchiuhtlicue. The three were sisters who together provided man with three life essentials: salt, food, and water.[1]

Other sources describe Huixtocihuatl's negative associations. In Codex Telleriano-Remensis, she is associated with the goddess Ixcuina, who represented filth and excrement. This relationship suggests that Huixtocihuatl was likely associated with urine, which was seen as salty, filthy, and impure.[3]

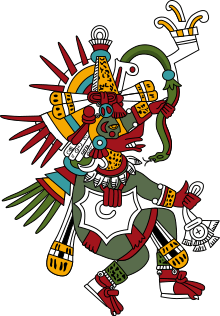

Iconography

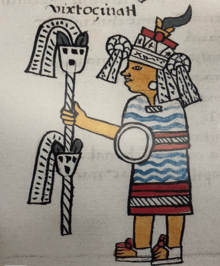

Primeros Memoriales, a manuscript written by Bernardino de Sahagún before his Florentine Codex, contains a description of Huixtochihuatl paired with an illustration.[4] The Aztecs believed that the essence of a deity could be captured by a human impersonator, or ixiptla, of the god. Primeros Memoriales therefore creates an illustration and description of the impersonator who would have embodied the salt god. The description closely follows the illustration, saying,

"Her facial paint is yellow./ Her paper crown has a quetzal feather crest./ Her gold ear plugs./ Her shift has the water design./ Her skirt has the water design./ Her small bells./ Her sandals./ Her shield has the water lily design./ In her hand is her reed staff."[4]

In the Florentine Codex, Sahagún expands upon his description of Huixtocihuatl. He describes Huixtocihuatl's appearance, as captured by the ixiptla as similar to that of a maize plant at antithesis. Sahagun describes the ixiptla as having yellow face paint and costume like the yellow of maize blossoms. He furthermore compares the feathers on her head to the green flowers of blossoming maize.[5] He says,

"Her [face] paint and ornamentation were yellow. This was of yellow ochre or the [yellow] of of maize blossoms. And [she wore] her paper cap with quetzal feathers in the form of a tassel of maize. It was of many quetzal feathers, full of quetzal feathers, so that it was covered with green, streaming down, glistening like precious green feathers." [2]

Ritual

During the Tecuilhuitontli, the seventh month of the Aztec calendar which occurred in June, there was a festival in her honor.[1] During the festival, one woman was considered to be the ixiptla, or the embodiment, of Huixtochiuatl. That woman would be sacrificed by the end of the festival.[6] Salt makers would honor her with dances that lasted for ten days.[2] Daughters of the salt-makers engaged in these dances[1]. The dancers wore garlands of iztauhyatl, the flower artemisia, while those watching the festival carried the flower.[1] On the last day of Tecuilhuitontli, the sacrifice of the ixiptla occurred on the shrine dedicated to Tlaloc on the Templo Mayor. Dancers escorted her to the temple, and captives were sacrificed along with the ixiplta.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Joseph,, Kroger, (2012). Aztec goddesses and Christian Madonnas : images of the divine feminine in Mexico. Granziera, Patrizia,. Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate. ISBN 9781409435976. OCLC 781499082.

- 1 2 3 1499-1590., Bernardino, de Sahagún, (1970). General history of the things of New Spain : Book I, the Gods. Anderson, Arthur J. O., Dibble, Charles E. (2nd ed., rev ed.). Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of American Research. p. 86. ISBN 9780874800005. OCLC 877854386.

- ↑ The Art and iconography of late Post-Classic central Mexico : a conference at Dumbarton Oaks, October 22nd and 23rd, 1977. Boone, Elizabeth Hill., Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. 1982. ISBN 0884021106. OCLC 8306454.

- 1 2 Sahagún, Bernardino de (1997). Primeros Memoriales (1590). Sullivan, Thelma D. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma. p. 106. ISBN 0806157496. OCLC 988659818.

- ↑ Grigsby, Thomas L.; de Leonard, Carmen Cook (1992). "Xilonen in Tepoztlán: A Comparison of Tepoztecan and Aztec Agrarian Ritual Schedules". Ethnohistory. 39 (2): 121. doi:10.2307/482390.

- ↑ Monaghan, Patricia (2009). Encyclopedia of Goddesses and Heroines. ABC-CLIO.