Chalchiuhtlicue

Chalchiuhtlicue [t͡ʃaːɬt͡ʃiwˈt͡ɬikʷeː] (from chālchihuitl [t͡ʃaːɬˈt͡ʃiwit͡ɬ] "jade" and cuēitl [kʷeːit͡ɬ] "skirt") (also spelled Chalciuhtlicue, Chalchiuhcueye, or Chalcihuitlicue) ("She of the Jade Skirt") is an Aztec deity of water, rivers, seas, streams, storms, and baptism. Chalchiuhtlicue was also associated with fertility and was the patroness of childbirth.[1] Chalchiuhtlicue was highly revered in Aztec culture at the time of the Spanish conquest and she was an important deity figure in the Postclassic Aztec realm of central Mexico.[2] Chalchiuhtlicue belonged to a larger group of Aztec rain gods[3] and she is closely related to another Aztec water god, Chalchiuhtlatonal.[4]

Mythology

_01.jpg)

Chalchiuitlicue directly translates to "Jade her skirt," however, her name is most commonly interpreted as "she of the jade skirt."[3] She was also known as Matlalcueitl, "Owner of the green skirt," by the Tlaxcalans, an indigenous group who inhabited the republic of Tlaxcala. Most legends describe Chalchiuitlicue as married to the rain god, Tlaloc. However, some myths describe her as the sister of Tlaloc,[5] or the wife of Xiuhtecuhtli (also called Huehueteotl).[6] Chalchiuitlicue was also the mother of Tecciztecatl, an Aztec moon god.

In Aztec religion, Chalchiuitlicue helped Tlaloc to rule the paradisial kingdom of Tlalocan. Chalchiutlicue brought fertility to crops and is thought to have protected women and children.

Chalchiutlicue's association with both water and fertility is derived from the Aztecs' common association of the womb with water. This dual role gave her both life-giving and a life-ending role in Aztec religion.[7] In the Aztec creation myth of the Five Suns, Chalchiuhtlicue presided over the Fourth Sun, the fourth creation of the world. It is believed that Chalchiuhtlicue retaliated against Tlaloc's mistreatment of her by releasing 52 years of rain, causing a giant flood which caused the Fourth Sun to be destroyed.[8] She built a bridge linking heaven and earth and those who were in Chalchiuhtlicue's good graces were allowed to traverse it, while others were turned into fish. Following the flood, the Fifth Sun, which we now occupy, developed.

Additionally, Chalchiutlicue was credited with the death of many men who died in canoe or drowning accidents.[9]

Archaeological records

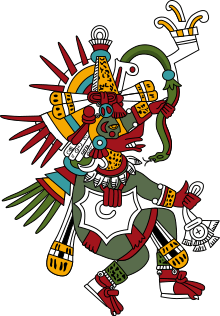

Chalchiutlicue is depicted in several central Mexican manuscripts, including the Pre-Columbian Codex Borgia (plates 11 and 650), the 16th century Codex Borbonicus (page 5), Codex Ríos (page 17), and the Florentine Codex, (plate 11). When she is represented through sculpture, she is often carved from green stone in accordance with her name.

The Pyramid of the Moon is a large pyramid located in Teotihuacán, the dominant political power in the central Mexican region during the Early Classic period (ca. 200–600 CE). The pyramid is thought to have been at one point dedicated to Chalchiutlicue. It accompanies The Pyramid of the Sun, which is thought to have been dedicated to Chalchiutlicue's husband, Tlaloc.

In the mid 19th century, archaeologists unearthed a 20-tonne (22-short-ton) monolithic sculpture depicting a water goddess that is believed to be Chalchiuhtlicue from underneath The Pyramid of the Moon. The sculpture was excavated from the plaza forecourt of the Pyramid of the Moon structure. The sculpture was relocated by Leopoldo Batres to Mexico City in 1889, where it is presently in the collection of the Museo Nacional de Antropología.[10]

Visual representations

To the Aztec people, Chalchihuitlicue was seen as a flowing river, producing a prickly pear tree encumbered with a tremendous amount of fruit. The fruit was a symbol for the human hearts that were sacrificed to the goddess. Chalchihuitlicue's distinctive hairdressing denotes her status.[11] Her headdress consists of several broad bands, likely made of cotton, trimmed with amaranth seeds. Large round tassels fall from sides of the goddess's headdress. Chalchihuitlicue was considered to be a beautiful woman whose clothing is that of a noble woman. She wears an extravagant shawl adorned with tassels and a green skirt. A stream of water, which usually includes a male and female baby, is often shown flowing from the goddess’ skirt. In addition, depictions of Chalchihuitlicue often show her carrying a cross. The Aztecs considered the cross to be a symbol of fertility, as it symbolized the four winds that brought rain to water the crops.

Cult and rites

Five of the twenty big celebrations in the native calendar were dedicated to Chalchiutlicue and her husband, Tlaloc. During these celebrations, priests dove into a lake and imitated the movements and the croaking of frogs, seeking to bring rain.

Chalchiutlicue presides over the day 5 Serpent and the trecena of 1 Reed. Her feast was celebrated in the ventena of Etzalqualiztli.[9] She was responsible for bringing about good harvest to the crops. She was connected with serpents, maize, and shells.

Childbirth

As Chalchiutlicue was the guardian of the children and new born, she played a central role in the process of childbirth. Chalchiutlicue was worshiped by many married women, who often would dedicate their nuptials to her. As mothers and babies often died in the process of childbirth, the role of the midwife was of utmost importance in the process. [12] During labor the midwife would speak to the newborn and then implore the gods that the baby's birth insure a prime place among them. After cutting the umbilical cord, the midwife would wash the new baby with customary greeting to Chalchiutlicue. Four days after the birth, the child was given a second bath and a name. According to the customs and tradition, the family and relatives prepared everything for the big celebration with food and drinks. The family of the baby would send for the midwife to lead the rite. After of the rising of the sun the midwife would place a bowl of water in the middle of the patio and hold the naked child with both hands. If the baby was a boy, he had a small shield, a bow and four little arrows; if the baby was a girl, she had a huipilli, distaff and a spindle. As reported by Sahagún's informants, the midwife would say in florid language: "My son, the gods Ometecutli and Omecioatl who realm in the ninth and tenth heavens, have begotten you in this light and brought you into this world full of calamity and pain take then this water, which will protect you life, in the name of the goddess Chalchiutlicue." Then with her right hand she would sprinkle water at the head of the child and say, "Behold this element without whose assistance no mortal being can survive." She also would sprinkle water on the breast of the baby saying, "Receive this celestial water that washes impurity from your heart." Then she would go again to the head and say, "Son receive this divine water, which must be drank that all may live that it may wash you and wash away all your misfortunes, part of the life since the beginning of the world: this water in truth has a unique power to oppose misfortune." At the end, she would wash the entire body of the baby, "In which part of you is unhappiness hidden? Or in which part are you hiding? Leave this child, today, he is born again in the healthful waters in which he has been bathed, as mandated by the will of the god of the sea Chalchiutlicue."

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:Chalchiuhtlicue. |

References

- ↑ Read & González 2002: 140–142

- ↑ According to the 16th-century Dominican friar and historian Diego Durán. "Universally revered" is quoted from his Book of the Gods and Rites, written 1574-1576 and published in English translation (Durán 1971: 261), as cited by Read & González 2002: 141.

- 1 2 de Bernardino, Sahagún (1970). Florentine Codex: General history of the things of New Spain: Book I, the Gods. Anderson, Arthur J. O., Dibble, Charles E. (2nd ed., rev ed.). Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of American Research. p. 6. ISBN 9780874800005. OCLC 877854386.

- ↑ Miller & Taube 1993: 60; Taube 1993: 32–35.

- ↑ "Chalchuitlicue Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ "Xiuhtecuhtli". azteccalendar.com.

- ↑ Miller & Taube 1993: 60

- ↑ Taube 1993:34–35

- 1 2 Sahagun, Bernardino de (1970). Florentine Codex. University of Utah Press. p. 6. ISBN 0874800005.

And sometimes she sank men in the water; she drowned them. The water was restless: the waves roared; they dashed and resounded. The water was wild.

- ↑ Berlo 1992: 138; Pasztory 1997: 87–89.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-03-15. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=TKE_J2M6P-8C&pg=PA68&dq=Chalchiutlicue+rites&sig=qQdfuAd6dTo1Ir__xgbFBDMuSR4#PPA67,The Mexican Treasury:The Writings of Dr. Francisco Hernández, M1

Bibliography

- Berlo, Janet Catherine (1992). "Icons and Ideologies at Teotihuacan: The Great Goddess Reconsidered". In Janet Catherine Berlo (ed.). Art, Ideology, and the City of Teotihuacan: A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 8 and 9 October 1988. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. pp. 129–168. ISBN 0-88402-205-6. OCLC 25547129.

- Durán, Diego (1971) [1574–79]. Book of the Gods and Rites and The Ancient Calendar. Civilization of the American Indian series, no. 102. Translated and edited by Fernando Horcasitas and Doris Heyden, with a Foreword by Miguel León-Portilla (translation of Libro de los dioses y ritos and El calendario antiguo, 1st English ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0889-4. OCLC 149976.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.

- Pasztory, Esther (1997). Teotihuacan: An Experiment in Living. foreword by Enrique Florescano. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-292-76597-5. OCLC 56405008.

- Read, Kay Almere; Jason J. González (2002). Handbook of Mesoamerican Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs of Mexico and Central America. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514909-2. OCLC 77857686.

- Taube, Karl A. (1993). Aztec and Maya Myths (4th University of Texas printing ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-78130-X. OCLC 29124568.