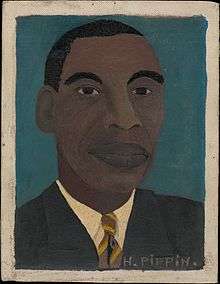

Horace Pippin

| Horace Pippin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

February 22, 1888 West Chester, Pennsylvania |

| Died | July 6, 1946 (aged 58) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

Horace Pippin (February 22, 1888 – July 6, 1946) was a self-taught African-American painter. The injustice of slavery and American segregation figure prominently in many of his works.

A Pennsylvania State historical Marker was placed at 327 Gay Street, West Chester, Pennsylvania, to commemorate his accomplishments and mark his home where he lived at the time of his death.[1]

Early life

He was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and grew up in Goshen, New York. There he attended segregated schools until he was 15, when he went to work to support his ailing mother.[2] As a boy, Horace responded to an art supply company's advertising contest and won his first set of crayons and a box of watercolors. As a youngster, Pippin made drawings of racehorses and jockeys from Goshen's celebrated racetrack. Prior to 1917, Pippin variously toiled in a coal yard, in an iron foundry, as a hotel porter and as a used-clothing peddler.[3] He was a member of St. John's African Union Methodist Protestant Church.[4]

World War I

Pippin served in K Company, 3rd Battalion of the 369th infantry, the famous Harlem Hellfighters, in Europe during World War I, where he lost the use of his right arm after being shot by a sniper. He said of his combat experience:

I did not care what or where I went. I asked God to help me, and he did so. And that is the way I came through that terrible and Hellish place. For the whole entire battlefield was hell, so it was no place for any human being to be.[5]

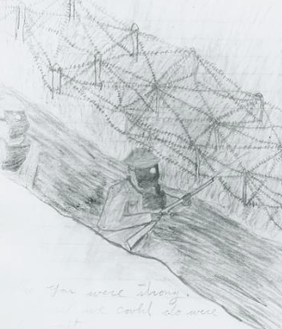

While in the trenches, Pippin kept an illustrated journal which gave an account of his military service.[6][7]

- Horace Pippin's War Diary Notebooks, 1917–18

Three Soldiers on March

Three Soldiers on March Soldiers with Gas Masks in Trench

Soldiers with Gas Masks in Trench

Artist

Pippin initially took up art in the 1920s to strengthen his wounded right arm. His activity as a painter began in earnest around 1930, when he completed his first oil painting, The End of the War: Starting Home. By the late 1930s, critic Christian Brinton, artists N. C. Wyeth and John McCoy, collector Albert C. Barnes, dealer Robert Carlen and curators Dorothy Miller and Holger Cahill championed Pippin's distinctive paintings that captured his childhood memories and war experiences, scenes of everyday life, landscapes, portraits, biblical subjects, and American historical events. Pippin enrolled in art classes at the Barnes Foundation during autumn 1939 and spring 1940 semesters.[3]

One of his best-known paintings, his Self-portrait of 1941, shows him seated in front of an easel, cradling his brush in his right hand (he used his left arm to guide his injured right arm when painting). His painting of John Brown Going to his Hanging (1942) is in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

Pippin explained his creative process: "The pictures which I have already painted come to me in my mind, and if to me it is a worth while picture, I paint it."[8]

Horace Pippin, John Brown Going to His Hanging

Horace Pippin, John Brown Going to His Hanging

Among Pippin's work there are many genre paintings, such as the Domino Players (1943), in the Phillips Collection, Washington D.C., and several versions of Cabin in the Cotton. His portraits include a depiction of the contralto Marian Anderson singing, painted in 1941. He also painted landscapes and religious subjects.

In the eight years between his national debut in the Museum of Modern Art's traveling exhibition “Masters of Popular Painting” (1938) and his death at the age of fifty-eight, Pippin's recognition increased on the east and west coasts. During this period, he had three solo exhibitions (1940, 1941, and 1943) at the Carlen Gallery, Philadelphia, PA and solo exhibitions at the Arts Club of Chicago (1941), and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1942), while private collections and museums such as the Barnes Foundation, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, acquired his works. His paintings were featured in national surveys held at the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, PA; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Dayton Art Institute, OH; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Newark Museum, Newark, NJ; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA. and Tate Gallery, London, UK.[3]

The last painting Pippin did before he died in 1946 was called Man on a Bench. In describing the work, Romare Bearden said: "the man, I think, symbolizes Pippin himself, who, having completed his journey and his mission, sits wistfully, in the autumn of the year, all alone on a park bench."[9]

In 1947 critic Alain Locke described Pippin as "a real and rare genius, combining folk quality with artistic maturity so uniquely as almost to defy classification."

Collections and retrospective exhibitions

Although he painted only about 140 works, concentrations of his work can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, N.Y.; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA; the Brandywine River Museum, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania; the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.; Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD; and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA.

Pippin has been the subject of three major retrospective exhibitions and catalogues since his death:

- Horace Pippin. Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., February 25–March 1977; Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, April 5–30, 1977; and Brandywine River Museum, Chadds Ford, Pa., June 4–September 5, 1977.

- I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, January 21–April 17, 1994; Art Institute of Chicago, April 30–July 10, 1994; Cincinnati Art Museum, July 28–October 9, 1994; Baltimore Museum of Art, October 26, 1994 – January 1, 1995; and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 1–April 30, 1995.

- Horace Pippin: The Way I See It. Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, Pa., April 25–July 19, 2015

Notes

- ↑ "Horace Pippin - Pennsylvania Historical Markers on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ↑ Forgey, 1977, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 Judith Stein. I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin. New York, 1993.

- ↑ William E. Krattinger (December 2009). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Olivet Chapel". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Pippin, Horace." Grolier Encyclopedia of Knowledge, volume 15, copyright 1991.

- ↑ Horace Pippin Notebook and Letters Online at the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art

- ↑ "Detailed description of the Horace Pippin notebooks and letters, circa 1920, 1943 - Digitized Collection | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". www.aaa.si.edu. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ↑ American folk painters of three centuries. Lipman, Jean; Armstrong, Tom; Whitney Museum of American Art. Hudson Hills Press. 1980. ISBN 0933920059.

- ↑ Bearden, Romare (1977). Horace Pippin. Washington, D.C: The Phillips Collection.

Sources

- Forgey, Benjamin, "Horace Pippin's 'personal spiritual journey'", ARTnews 76 (Summer 1977): pp. 74-xx

- "Pippin, Horace." Grolier Encyclopedia of Knowledge, volume 15, copyright 1991. Grolier Inc., ISBN 0-7172-5300-7

- Barnes, Albert. "Horace Pippin." In Horace Pippin Exhibition, Carlen Gallery. Philadelphia, 1940.

- Bearden, Romare. "Horace Pippin." In Horace Pippin, The Phillips Collection. Washington, D.C., 1976.

- Locke, Alain. "Horace Pippin." In Horace Pippin Memorial Exhibition, The Art Alliance, April 8–May 4, 1947. Philadelphia, 1947.

- Rodman, Selden. Horace Pippin: A Negro Painter in America. New York, 1947.

- Judith E. Stein (1993). "I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin". Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2015 – via http://judithestein.com.

Further reading

- I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin, exh. cat., Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1993.

- Horace Pippin: The Way I See It. Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, Pa., 2015

- Suffering and Sunset: World War I in the Art and Life of Horace Pippin by Celeste-Marie Bernier, 2015, Temple University Press

- Bryant, Jen. A Splash of Red: The Life and Art of Horace Pippin. New York, 2013.

External links

- Horace Pippin links

- Horace Pippin Notebook and Letters Online at the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|