History of the Knights of Columbus

The history of the Knights of Columbus begins with its founding in 1882 by Father Michael J. McGivney at St. Mary's Parish in New Haven, Connecticut. Originally intended to be a mutual benefit society, it has since grown into a Catholic anti-defamation league, a leading philanthropic society, and the world's largest Catholic fraternal service organization.

Early history

Founding

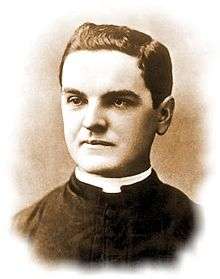

Michael J. McGivney, an Irish-American Catholic priest, founded the Knights of Columbus in New Haven, Connecticut. He gathered a group of men from St. Mary's Parish for an organizational meeting on October 2, 1881. Several months later, the Order was incorporated under the laws of the state of Connecticut on March 29, 1882.[1] McGivney had originally conceived of the name "Sons of Columbus" but James T. Mullen, who would ascend to become the first Supreme Knight, was successful in suggesting that "Knights of Columbus" better expressed the ritualistic nature of the new organization and drew from positive historical associations.[2]

The Order was intended to be a mutual benefit society. As a parish priest in an immigrant community, McGivney saw what could happen to a family when the main income earner died. This was before most government support programs were established. He wanted to provide insurance to care for the widows and orphans left behind. In his own life, he temporarily had to suspend his seminary studies to care for his family after his father died.[3]

Because of religious and ethnic discrimination, Roman Catholics in the late 19th century were regularly excluded from labor unions, popular fraternal organizations, and other organized groups that provided such social services.[4] Papal encyclicals issued by the Holy See also prohibited Catholics from participating as lodge members within Freemasonry. McGivney intended to create an alternative organization. He also believed that Catholicism and fraternalism were compatible and wanted to found a society to encourage men to be proud of their American-Catholic heritage.[5][6]

Fraternal organizations, which combined social aspects and ritual, were especially flourishing during the latter third of the nineteenth century, the so-called "Golden Age of Fraternalism.[7][6] New Haven's Irish Catholic men of the era could have joined one of many other organizations,[nb 1] and Catholics of other ethnicities had additional options.[6]

McGivney traveled to Boston to examine the Massachusetts Catholic Order of Foresters and to Brooklyn, New York to learn about the recently established Catholic Benevolent League, both of which offered insurance benefits. He found the latter to be lacking the excitement he thought was needed if his organization were to compete with the secret societies of the day. He explored establishing a New Haven Court of the Foresters, but the group's charter in Massachusetts limited them to operating within that Commonwealth. McGivney's committee of St. Mary's parishioners decided to form a new club.[8][6]

Catholic and American

Taking the name of Columbus was partially intended as a mild rebuke to Anglo-Saxon Protestant leaders, who upheld the explorer (a Genovese Italian Catholic who had worked for Catholic Spain) as an American hero, yet simultaneously sought to marginalize recent Catholic immigrants.[9] In taking Columbus as their patron, the founders expressed their belief that not only could Catholics be full members of American society, but that they were instrumental in its foundation.[9][10]

Of the first 28 members of the first council, 16 were born in Ireland.[6] A majority of the first generation of Knights across the Order were immigrants.[6] Joining the Knights gave the recent immigrants a mantle of "middle-class American respectability without forfeiting their preexisting ethnic and religious identities,"and gave them "a rhetorical foundation for claims to full American citizenship."[6]

Unlike many other Catholic organizations of the time, though, the Knights placed a greater emphasis on loyalty to their new world republics than they did on old ethnic divisions of the old world.[11][12] McGivney envisioned an organization that would imbue members "with a zealous pride in one's American-Catholic heritage."[11][5] In Canada, a similar sentiment held among early members.[13]

The model of Christian knighthood promoted by the Order "provided Catholic men with a positive interpretation of the separation they would have experienced relative to the Protestant-dominated social and political context in New Haven."[6] The Order effused a sense that as Catholic gentlemen and Knights of Columbus they should be regarded as exemplars of virtue, not aberrations from the dominant Protestant model of manhood.[6]

High standards for members

The Order held members to a higher standard than did other organizations of the time.[6] Membership was limited to "practical" Catholic men or "Catholics in good standing" at the time of their application.[6] According to McGiveny, the "reason our examination is so strict is, that we deem it better for all concerned to have five hundred sound and good men in our order than five thousand otherwise."[6] Only "worthy" men were permitted to join.[6]

Perhaps to counteract the perception of the Irish as drunks or lower class, sobriety was demanded of members.[6] The Order was the only fraternal organization in America at the time whose constitution did not exclude African American members,[14] but "liquor dealers" were expressly prohibited from joining.[6] Newspapers at the time published "sensationalized accounts of inebriated soirees" held by other organizations for Irishmen, but the "Knights' social functions--formal dinners, balls, and cotillions--also reflected members' aspirations toward middle-class refinement."[6]

At the Board of Government convention in 1887, a proposal was made to admit non-Catholics, but was strongly opopsed by Supreme Knight John J. Phelan: "The Order cannot stultify itself or allow itself to masquerade in the garb of sanctity it wittingly desecrates. Our laws design us to be Catholics pure and simple."[6]

Growth

Although its first councils were all in Connecticut, the Order spread throughout New England and the United States in subsequent years. The Order experienced "unparalleled success" in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[6] It outpaced all other Catholic fraternities of the era.[6]

By the time of the first annual convention in 1884, the Order was prospering. The five councils throughout Connecticut had a total of 459 members. Groups from other states were requesting information.[15] By 1889, there were 300 councils comprising 40,000 knights. Twenty years later, in 1909, there were 230,000 knights in 1,300 councils.[16]

As the order expanded outside of Connecticut, structural changes in the late 1880s and 1890s were instituted to give the Knights a federalist system with local, state, and national branches of government.[17] This allowed them to coordinate activities across states and localities.[18]

The Charter of 1899 included four statements of purpose, including: "To promote such social and intellectual intercourse among its members as shall be desirable and proper, and by such lawful means as to them shall seem best."[19] The new charter showed members' desire to expand the organization beyond a simple mutual benefit insurance society. Associate members who did not purchase life insurance were permitted to join in 1892.[11]

Outside the United States

The first councils in Mexico and the Philippines were founded in 1905.[20] Cuba's first council was established in 1909.[21]

Canada

Canada Council number 284 was established in 1897 in Montreal. It was largely anglophone with only six French Canadian members. Its first Grand Knight, however, was J.J. Guerin, a member of the Quebec Legislature.[10] Archbishop Paul Bruchesi of Montreal and several other bishops initially opposed the Knights' expansion into Canada.[10] Private negotiations with Cardinal James Gibbons assuaged the fears of most.[10]

In Toronto, however, Archbishop Denis T. O'Connor blocked efforts to expand into his archdiocese on the grounds that there were already too many Catholic societies in existence.[10] Upon his retirement in 1908, new Archbishop Fergus McEvay allowed a council to be formed on the condition that he be allowed to appoint the council's chaplain.[22] The 131 charter members swelled to over 600 in just eight years, and it became the largest council in Ontario with nearly 10% of all knights in the province.[23]

The Knights grew rapidly in Canada, and by 1904 there was a state council in Quebec and one for Ontario and the Maritimes.[10] Six years later, in 1910, the 60 Canadian councils had 9,000 members.[10] While there were other Catholic fraternal societies in Canada in the 19th century, "none recruited as vigorously, grew as rapidly, or captured the public attention and imagination as did the caped and plumed Knights of Columbus."[11] By then, the Knights were seen as "those laymen who could successfully defend the Church from external opposition when required and, more importantly, could voice the opinions and teachings of the Church, bringing them to bear of the problems of Canadian society."[24]

Forty years after its founding, the Knights of Columbus had spread into Canada and had become a powerful enough presence there to generate a backlash from the nationalist francophone community.[25] French Canadians created a competing society, the Ordre de Jacques Cartier, in 1926.[26]

Columbian manhood

In contrast to most of the other fraternal societies of the era, which provided an escape from the extreme gender bifurcation of the Victorian era, "literature produced by the Knights of Columbus valorized affectionate bonds between men and their mothers, and idealized the relationship between men and their wives and children."[6] The early records of the Order did not display the same level of anxiety that other organizations did about the feminization of men that arises from a commitment to family and faith.[6]

Instead, Columbian manhood in the early documents equated manhood with the performance of one's duties as a Catholic and father.[6] It emphasized being chivalrous, a loving husband, a good Catholic, and a solidarity with one's fellow man.[6] Knights were seen as fathers and parishioners first, not as men trying to escape those more feminine spheres as other organizations often promoted.[6]

Two years after its founding, in a series of letters to the editor of the Connecticut Catholic, William Geary encouraged young men to join the Order by appealing to their sense of fraternal duty to family, faith, parish, and country.[6] Joining the Knights, Geary argued, allowed Catholic men to fulfill their duty to their families by providing for them in case he was injured or killed and unable to provide.[6] This sense of duty to faith and family was also reflected in the public events the Order conducted during its first two decades of existence.[6] This definition of manhood was also universal, available to every man regardless of his class or social position.[6]

The Columbiad, "a monthly paper devoted to the interests of the Knights of Columbus," published an article in November 1903 comparing Knights of Columbus to chivalrous medieval Christian knights, extolling their shared traits of vigorous, virtuous, manly faith.[6] "The Christian Knight," according to The Columbiad, "was the knight of spotless life, of Christian faith, of dauntless courage, of unblemished honor, faithful to his word, loyal and true, like the knights of King Arthur."[6] Both had "manly virtue, valor, humanity, courtesy, justice and honor" and both were called to "rescue the helpless from captivity, to protect the orphans and widows, and assist the sick and poor."[6] Knighthood, in the Columbian model, "valorized individual self-sacrifice for greater social welfare."[6]

Columbian men were also expected to take an active role in fatherhood and child rearing.[6] The Columbiad affirmed the role and duty of the father, encouraging men to show affection and to "assist their children intelligently and sympathetically to overcome" faults and character flaws.[6] Men were also expected to have close and supportive relationships with their wives and mothers.[6]

Creation of the Fourth Degree

From the earliest days of the Order, members wanted to create a form of hierarchy and recognition for senior members;[27] this issue was discussed at the National Meeting of 1899.[28] As early as 1886, Supreme Knight James T. Mullen had proposed a patriotic degree with its own symbolic dress.[29]

About 1,400 members attended the first exemplification of the Fourth Degree at the Lenox Lyceum in New York on February 22, 1900.[27][28] The event was infused with Catholic and patriotic symbols, imagery that "celebrated American Catholic heritage."[30] The two knights leading the ceremony, for example, were the Expositor of the Constitution and the Defender of the Faith.[30] The ritual soon spread to other cities.[27] The new Fourth Degree members returned to their councils, forming assemblies composed of members from several councils. Those assemblies chose the new members.[31]

In 1903, the Board of Directors officially approved a new degree exemplifying patriotism Order-wide, using the New York City model.[27] The Order had a "desire to receive within its ranks only the best" and intended the men should be practicing Catholics. As one measure, each candidate was required to submit a certificate from his parish priest attesting that he had received Holy Communion within the past two weeks.[32]

War efforts

Cristero War

Following the Mexican Revolution, the new government began persecuting the church. To destroy the church's influence over the Mexican people, anti-clerical statutes were inserted into the Constitution, beginning a 10-year persecution of Catholics that resulted in the deaths of thousands, including several priests who were also knights of Columbus. Leaders of the order began speaking out against the Mexican government. Columbia, the official magazine of the Knights, published articles critical of the regime. After the November 1926 cover of Columbia portrayed Knights carrying a banner of liberty and warning of "The Red Peril of Mexico", the Mexican legislature banned both the order and the magazine throughout the country.[33]

In 1926, a delegation of Supreme Council officers met with President Calvin Coolidge to share with him their concerns about the persecution of Catholics in Mexico. The order subsequently launched a $1-million campaign to educate Americans about the attacks on Catholics and the church in the Cristero War.[34] The organization produced pamphlets in English and Spanish denouncing the anticlerical Mexican government and its policies. So much printed material was smuggled into Mexico that the government directed border guards be aware of women bringing Catholic propaganda into the country hidden in their clothes.[35][36] Twenty-five martyrs from the conflict would eventually be canonized, including six knights.[37][38]

Supreme Treasurer Daniel J. Callahan, a well known civic leader in Washington, convinced Senator William E. Borah to launch an investigation in 1935 into human rights violations in Mexico.[39] The order was praised for their efforts by Pope Pius XI in his encyclical, Iniquis afflictisque.[40]

World War I

To prove that good Catholics could also be good Americans, and to mitigate some of the American Anti-Catholicism prevelent in the United States at the time, the Knights supported both the war effort and the troops during World War I. Thousands of knights served in the American Expeditionary Forces, including William T. Fitzsimons, considered the first American officer killed in the war.[41] On April 14, 1917, soon after the United States entered the war, the board of directors passed a resolution calling for

the active cooperation and patriotic zeal of 400,000 members of the order in this country to our Republic and its law, pledge their continued and unconditional support to the President and Congress of the Nation, in their determination to protect its honor and its ideals of humanity and right.[42]

Supreme Knight James A. Flaherty proposed to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson that the Order establish soldiers' welfare centers in the U.S. and abroad. The organization already had experience, having provided similar services to troops encamped on the Mexican border during Pershing's expedition of 1916.[43] Staff and chaplains were sent to every Army camp and cantonment.[44]

With the slogan "Everyone Welcome, Everything Free," the "huts" became recreation/service centers for doughboys regardless of race or religion.[44][45] They were staffed by "secretaries," commonly referred to as "Caseys" (for K of C) who were generally men above the age of military service. The centers provided basic amenities not readily available, such as stationery, hot baths, and religious services.[46] One well-known "Casey" was major league baseball player Johnny Evers of ""Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance," who traveled to France as a member of the Knights of Columbus to organize baseball games for the troops.[47] A total of 260 buildings were erected and 1,134 secretaries, of which 1,075 were overseas, staffed them.[44] In Europe, headquarters were established in London and Paris.[44] The order continued this work until November 1919, at which point the effort was taken over by the federal government.[44]

To pay for these huts and their staff, the order instituted a per capita tax on the membership to raise $1 million.[44] Local councils undertook their own fundraising drives which resulted in an additional $14 million to support the effort.[44] In 1918, just before the war ended, the Knights and other organizations undertook another effort to raise funds to support the welfare of the men fighting abroad.[44] The amount apportioned to the order and the National Catholic War Council totaled $30 million which, when combined with earlier efforts, funded efforts to support troops both in the United States and overseas.[44] After the war, the Knights became involved in education, occupational training, and employment programs for the returning troops.[43][44]

As a result of their efforts during the war, "the Order was infused with the self-confidence that it could respond with organizational skill and with social and political power to any need of Church and society. In this sense, the K. of C. reflected the passage of American Catholicism from an immigrant Church to a well-established and respected religious denomination which had proven its patriotic loyalty in the acid test of the Great War."[48][49] In Canada, the order's charity work a "fusion of Catholicism and Canadian identity among Catholic lay-men but [which also] signaled significant changes in Protestant Toronto's acceptance of English-speaking Catholics as loyal citizens."[13]

According to Supreme Knight Flaherty, "The war provided us with an opportunity to put ourselves before the public in a most favorable light."[50] In fact, the Knights' efforts attracted so much positive publicity that anti-Catholics and opponents of the order began to complain.[50]

World War II

Shortly after the United States entered the Second World War, the order established a War Activities Committee to keep track of all activities undertaken during the war.[51] They also, in January 1943, established a Peace Program Committee to develop a "program for shaping and educating public opinion to the end that Catholic principles and Catholic philosophy will be properly represented at the peace table at the conclusion of the present war."[52] The committee conferred with scholars, theologians, philosophers, and sociologists and proposed a program adopted at the 1943 Supreme Convention.[53][54]

Canadian Knights

Less than two weeks after the outbreak of World War II, on September 13, 1939, Canadian Supreme Director Claude Brown wired each Canadian state deputy to inform them of his plans to establish a welfare program comparable to the "huts" sponsored by the order during World War I.[55] The Canadian government accepted his proposal by the end of October, and formed a unified organization including the Knights, the YMCA, the Salvation Army, and the Canadian Legion.[55] Between December 1939 and April 1940, the Canadian Knights raised almost $230,000, "an extraordinary amount considering the fact that there were relatively few Knights in Canada."[55]

In large cities, recreation centers were established, and morale programs were run in a number of training camps.[56] Hostels were established for servicemen on furloughs first in Canada, then England, and eventually across Europe.[56] Sporting events were organized, musical and comedy shows were produced, and even academic courses and a library were provided.[56]

Recognizing the danger the volunteers who staffed these camps were undertaking, the Canadian government gave them a stipend equal to that of a captain in the Canadian Army and made them eligible for retirement and disability pay.[56] F. O'Neil, who ran the Knights' recreation center in Hong Kong, was captured by the Japanese and was made a prisoner of war.[56] Six volunteers, including Brown, died during the war.[56]

Canadian Knights, and not the government, provided supplies for Catholic chaplains.[56] Bishop Charles Leo Nelligan of the Military Ordinariate of Canada wrote that

In Canada the Knights of Columbus Canadian Army Huts stretch like a golden chain from coast to coast, connecting up all out military camps and a large number of our newly established training centers. In each and every one of them is to be found a genial and capable staff, always ready and anxious to serve the troops.[56]

Supreme Knight Francis Matthews "expressed a feeling of pride" on behalf of the entire order at the Canadian Knights' efforts, and membership in Canada more than doubled between 1939 and 1947.[57]

Conflict with the Ku Klux Klan

Since its earliest days, the Knights of Columbus has been a "Catholic anti-defamation society."[58] These efforts increased during the 1920s as the Knights, the "pre-eminent Catholic fraternal organization,"[50] sought to correct misconceptions about Catholicism.[59]

Not long after the establishment of the Fourth Degree, during the nadir of American race relations, a bogus oath was circulated claiming that Fourth Degree Knights swore to exterminate Freemasons and Protestants. In addition, they purportedly were prepared to flay, burn alive, boil, kill, and otherwise torture anyone, including women and children, when called upon to do so by church authorities.[60][61] "It is a strange paradox," according to some commentators, that the degree devoted to patriotism should be accused of anti-Americanism.[62]

The "bogus oath" was based on a previous oath falsely attributed to the Jesuits more than three centuries earlier.[63] The Ku Klux Klan, which was growing into a newly powerful force through the 1920s, spread the bogus oath far and wide as part of their contemporary campaign against Catholics (which was part of a campaign against immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, of whom many were Catholic).[64][65][66] During the 1928 Presidential election, the Klan printed and distributed a million copies of the oath in an effort to defeat Catholic Democratic candidate Al Smith. Thomas S. Butler (R), U.S. Representative from Pennsylvania, read it into the Congressional Record.[67] The bogus oath was refuted by the Committee of Public Information, a propaganda agency of the U.S. Government established during World War I.[62]

Misunderstanding Catholicism, the Klan alleged that Knights were only loyal to the Pope and that they advocated the overthrow of the United States government.[68] Across the country, local, state, and the Supreme Councils offered rewards to anyone who could prove that the widely circulated oath was authentic.[69] No one could, but that did not stop the Klan from continuing to publish and distribute copies. Numerous state councils and the Supreme Council believed that this "violent wave of religious prejudice was actuated by mercenary motives." They believed publication would stop if the KKK were assessed fines or punished by jail time assessed. They began suing distributors for libel.[68] The KKK ended its publication of the false oath. As the Order did not wish to appear motivated by a "vengeful spirit," it asked for leniency from judges when sentencing offenders.[68]

To help combat this misconception, the K of C submitted the actual oath of Fourth Degree members for examination by various groups of prominent non-Catholic men around the country. Many made public declarations attesting to the loyalty and patriotism of the Knights.[70] After examining the true oath, a committee of high-ranking California Freemasons, a group identified as a target in the bogus oath, declared in 1914:

The ceremonial of the Order [of the Knights of Columbus] teaches a high and noble patriotism, instills a love of country, inculcates a reverence of civic duty and holds up the Constitution of our Country as the richest and most precious possession of a Knight of the Order.[71]

In Muncie, Indiana, a local council organized a march of 750 people to protest the KKK.[72]

Pierce v. Society of Sisters

After World War I, many native-born Americans had a revival of concerns about assimilation of immigrants and worries about "foreign" values; they wanted public schools to teach children to be American. Numerous states drafted laws designed to use schools to promote a common American culture, and in 1922, the voters of Oregon passed the Oregon Compulsory Education Act. The law was primarily aimed at eliminating parochial schools, including Catholic schools.[73][74] It was promoted by groups such as the Knights of Pythias, the Federation of Patriotic Societies, the Oregon Good Government League, the Orange Order, and the Ku Klux Klan.[75]

The Compulsory Education Act required almost all children in Oregon between eight and sixteen years of age to attend public school by 1926.[75] Roger Nash Baldwin, an associate director of the ACLU and a personal friend of then-Supreme Advocate and future Supreme Knight Luke E. Hart, offered to join forces with the Order to challenge the law. The Knights of Columbus pledged an immediate $10,000 to fight the law and any additional funds necessary to defeat it.[76]

The case became known as Pierce v. Society of Sisters, a seminal United States Supreme Court decision that significantly expanded coverage of the Due Process Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment. In a unanimous decision, the Court held that the act was unconstitutional and that parents, not the state, had the authority to educate children as they thought best.[77] It upheld the religious freedom of parents to educate their children in religious schools.

Racial integration in the U.S.

Postwar social unrest was also related to the difficulties of absorbing the veterans from the war in the job market. Competition among groups for work heightened tensions. In the 1920s there was growing anti-Semitism in the United States related to economic competition and the fears of social change from decades of changed immigration, a lingering anti-German sentiment left over from World War I, and anti-black violence erupted in numerous locations as well. In this period African Americans were leaving the South by the tens of thousands, to escape oppressive social conditions and find work in the North and Midwestern industrial cities, in what came to be called the Great Migration.

To combat the animus targeted at racial and religious minorities, including Catholics, the Order formed a historical commission which published a series of books on their contributions, among other activities.[78][59] The "Knights of Columbus Racial Contributions Series" of books included three titles: The Gift of Black Folk, by W. E. B. Du Bois, The Jews in the Making of America by George Cohen, and The Germans in the Making of America by Frederick Schrader.[78][59]

As the 20th century progressed, some councils in the United States became integrated, but many were not. Given the history of slavery and early development in the US, most African Americans were Protestant. But many in former French or Spanish territories had grown up Catholic. Church officials and organizations encouraged integration. By the end of the 1950s, Supreme Knight Luke E. Hart was actively encouraging councils to accept black candidates.[79] In 1963, Hart attended a special meeting at the White House hosted by President John F. Kennedy to discuss civil rights with other religious leaders. A few months later, a local KofC council rejected a black man's application because of his race, notwithstanding that he was a graduate of Notre Dame University. Six council officers resigned in protest, and the incident made national news. Hart declared that the process for membership would be revised at the next Supreme Convention, but died before he could see it take place.[80]

The 1964 Supreme Convention was scheduled to be held at the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans. A few days before the Convention, new Supreme Knight John W. McDevitt learned the hotel admitted only white guests, under the state's racial segregation policy. He threatened to move the Convention to another venue. The hotel changed its policy and so did the Order. The Convention amended the admissions rule to require that a new applicant could not be rejected by less than one-third of those voting. In 1972 the Supreme Convention amended its rules again, requiring a majority of members voting to reject a candidate.[81]

Recent history

| Year | Membership | Councils |

| 2018[82][83] | 1,967,585[nb 2] | 15,900 |

| 2013[84] | 1,843,587 | 14,606 |

| 2012[84] | 1,830,000 | 14,400 |

| 2011[84] | 1,820,000 | 14,200 |

| 2010[84] | 1,810,000 | 14,000 |

| 2009[84] | 1,790,000 | 13,700 |

| 1982[85] | 1,300,000 | <7,000 |

| 1964[80] | 1,000,000+ | |

| 1957[86] | 1,000,000 | |

| 1938[87] | 500,000 | |

| 1931[88] | 2,600 | |

| 1923[89] | 774,189 | 2,290 |

| 1917[42][90] | 400,000 | |

| 1914[91] | 300,000+ | |

| 1909[16] | 230,000 | 1300 |

| 1899[91][16] | 40,267 | 300 |

| 1897[92] | 16,651 | 195 |

| 1892[6] | 6,500 | |

| 1886[92] | 2,700 | 27 |

| 1884[15] | 459 | 5 |

According to Massimo Faggioli, the Knights of Columbus are "'an extreme version' of a post-Vatican II phenomenon, the rise of discrete lay groups that have become centers of power themselves."[49]

In 1959, Fidel Castro sent an aide to represent him at a Fourth Degree banquet in honor of the Golden Jubilee of the Order's entry into Cuba.[93] Supreme Knight Luke E. Hart attended a banquet in the Cuban Prime Minister's honor in April of that year sponsored by the Overseas Press Club.[93] He later sent him a letter expressing regret that they were not able to meet in person.[93]

Hart visited President and fellow Knight John F. Kennedy at the White House on Columbus Day, 1961.[nb 3] Hart presented Kennedy with a poster of the American flag with the story of how the Order got the words "under God" inserted in the Pledge of Allegiance.[94]

As the Order and its charitable works grew, so did its prominence within the Church.[95] The Supreme Board of Directors was invited to hold their April meeting at the Vatican in 1978, and the Board and their wives were received by Pope Paul VI.[95] Pope John Paul I's first audience with a layman was with Supreme Knight Dechant, and Pope John Paul II met with Dechant three days after his installation.[95]

Pope John Paul II traveled to the Dominican Republic and Mexico in 1978, and Dechant was invited to attend and welcome the Pope to the Americas.[95] It was also while there that Dechant was invited to establish the Order in the Dominican Republic.[95] During the pope's 1979 visit to the United States, the Supreme Officers and Board were the only lay organization to receive an audience.[96]

In 1997, the cause for McGivney's canonization was opened in the Archdiocese of Hartford. It was placed before the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in 2000. The Father Michael J. McGivney Guild was formed in 1997 to promote his cause, and it currently has more than 140,000 members.[97] Membership in the Knights of Columbus does not automatically make one a member of the guild, nor is membership restricted to Knights; members must elect to join. On March 15, 2008, Pope Benedict XVI approved a decree recognizing McGivney's "heroic virtue," significantly advancing the priest's process toward sainthood. McGivney may now be referred to as the "Venerable Servant of God." If the cause is successful, he would be the first priest born in the United States to be canonized as a saint.[98]

The Knights of Columbus were among the groups that welcomed Pope Benedict XVI on the South Lawn of the White House on April 16, 2008, the pontiff's 81st birthday, during his visit to the U.S.[99] In March 2016 the Knights of Columbus delivered to US Secretary of State John Kerry a 280-page report entitled Genocide Against Christians in the Middle East. This led the US State Department to declare that "ISIS's systematic massacre of Christians in the Middle East had reached genocidal proportions."[100]

Insurance program

| Year | Reserve Fund Assets |

| 1896[101] | $12,000 |

The original insurance system devised by McGivney gave a deceased Knight's widow a $1,000 death benefit. Each member was assessed $1 upon a death, and when the number of Knights grew beyond 1,000, the assessment decreased according to the rate of increase.[102] Each member, regardless of age, was assessed equally. As a result, younger, healthier members could expect to pay more over the course of their lifetimes than those men who joined when they were older.[103] There was also a Sick Benefit Deposit for members who fell ill and could not work. Each sick Knight was entitled to draw up to $5 a week for 13 weeks (roughly equivalent to $125.75 in 2009 dollars[104]). If he remained sick after that, the council to which he belonged determined the sum of money given to him.[105]

The need for a reserve fund for times of epidemic was seen from the earliest days, but it was rejected several times before finally being established in 1892.[106]

Since its first loan to St. Rose Church in Meriden, Connecticut in the late 1890s, the Knights of Columbus have made loans to parishes, dioceses, and other Catholic institutions.[107] By 1954, over $300 million had been loaned and the program "never lost one cent of principal or interest."[107]

In the post World War II era, the interest rates on long-term bonds dipped below levels at which the Order's insurance program could sustain itself, and Supreme Knight Hart moved the order into a more aggressive program of investing in real estate.[108] Under his leadership, the Order established a lease-back investment program in which the Order would buy a piece of property and then lease it back to the original owner "upon terms generally that would bring to our Order a net rental equal to the normal mortgage interest rate."[108]

Late in 1953 it was learned that the land upon which Yankee Stadium was built was for sale. On December 17, 1953, the Order purchased the property for $2.5 million and then leased it back for 28 years at $182,000 a year with the option to renew the lease for three additional terms of 15 years at $125,000 a year.[107] In 1971 the City of New York took the land by eminent domain.[109]

Between 1952 and 1962, 18 pieces of land were purchased as part of the lease-back program for a total of $29 million. During this time, the amount of money invested in common stock also increased.[107]

Modern program

| Year | Insurance in force (billions)[84] |

Assets (billions)[84] |

| 2012 | $88.4 | $19.4 |

| 2011 | $83.5 | $18.0 |

| 2010 | $79.0 | $16.9 |

| 2009 | $74.3 | $15.5 |

| 2008 | $70.1 | $14.1 |

The Order offers a modern, professional insurance operation with more than $100 billion of life insurance policies in force and $19.8 billion in assets as of June 2013,[110] a figure more than double the 2000 levels.[84][110] Nearly 80,000 life certificates were issued in 2013, almost 30,000 more than the Order's closest competitor, to bring the total to 1.73 million.[84] The program has a $1.8 billion surplus.[84]

Over $286 million in death benefits were paid in 2012 and $1.7 billion were paid between 2000 and 2010.[84] This is large enough to rank 49th on the A. M. Best list of all life insurance companies in North America.[111] Since the founding of the Order, $3.5 billion in death benefits have been paid.[112] Premiums in 2012 were nearly $1.2 billion, and dividends paid out totaled more than $274 million.[84] Over the same time period, annuity deposits rose 4.2%, compared to an 8% loss for the industry as a whole.[84]

Every day in 2012 more than $10 million was invested, for a total of $2.7 billion on the year, and an annual income of $905 million.[84] The Order maintains a two prong investment strategy. A company must first be a sound investment before stock in it is purchased, and secondly the company's activities must not conflict with Catholic social teaching.[84] Citing the awards they have won, the Order calls themselves "champions of ethical investing."[49] The Order also provides mortgages to churches and Catholic schools at "very competitive rates" through its ChurchLoan program.[84]

Products include permanent and term life insurance, as well as annuities, long term care insurance, and disability insurance.[110] The insurance program is not a separate business offered by the Order to others but is exclusively for the benefit of members and their families.[113] According to the Fortune 1000 list, the Knights of Columbus ranked 880 in total revenue in 2017[114] and, with more than 1,500 agents, was 925th in size in 2015.[84] All agents are members of the Order.

The Order's insurance program is the most highly rated program in North America.[84] For 40 consecutive years, the Order has received A. M. Best's highest rating, A++.[84][115] Additionally, the Order is certified by the Insurance Marketplace Standards Association for ethical sales practices.[116] Standard & Poor's downgraded the insurance program's financial strength/credit rating from AAA to AA+ in August 2011 not due to the Order's financial strength, but due to its lowering of the long-term sovereign credit rating of the United States to AA+.[117][118][nb 4] Additionally, the insurance program has a low 3.5% lapse rate of the 1.9 million members and their families who are insured.[84][110]

Supreme Knights

| Term of office | Supreme Knight | Prior office | Deputy Supreme Knight | Supreme Chaplain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

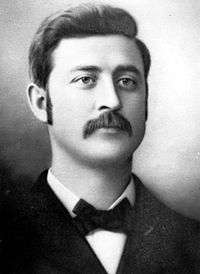

| 1 | February 2, 1882 to May 17, 1886 |  |

James T. Mullen | 1882[119] to | John T. Kerrigan | |||

| April 29, 1884[120] to | John Dowling | 1884[120] to 1890 | Michael J. McGivney | |||||

| 2 | May 17, 1886[121]to 1897 |  |

John J. Phelan | May 17, 1886[121] to | William Hassett | |||

| 3 | March 2, 1897 to February 8, 1898 |  |

James E. Hayes | First State Deputy of Massachusetts | 1897 to February 8, 1898 | John J. Cone[122] | ||

| 4 | February 8, 1898 to 1899 |  |

John J. Cone | First New Jersey State Deputy, Deputy Supreme Knight |

Vacant | |||

| Vacant | ||||||||

| 5 | April 1, 1899 to August 31, 1909 |  |

Edward L. Hearn | State Deputy of Massachusetts | April 1, 1899[123] to June 3, 1903[124] | John W. Hogan | ||

| 1901[34] to 1928[125] | Patrick McGivney | |||||||

| June 3, 1903[124] to | Patrick T. McArdle[126] | |||||||

| James A. Flaherty[127] | ||||||||

| 6 | September 1, 1909 to August 31, 1927 |  |

James A. Flaherty | Deputy Supreme Knight | 1909[125] to 1927[128] | Martin H. Carmody[125] | ||

| 7 | September 1, 1927 to August 31, 1939 | Martin H. Carmody | Deputy Supreme Knight, Michigan State Deputy |

1927[125] to 1933[129] | John F. Martin | |||

| 1928[125] to 1938[130] | John J. McGivney | |||||||

| 1933[129] to 1939 | Francis P. Matthews | |||||||

| 1938[130] to 1960[131] | Leo M. Finn | |||||||

| 8 | 1939 to 1945 |  |

Francis P. Matthews | Deputy Supreme Knight[130] | 1939 to 1945 | John E. Swift | ||

| 9 | 1945 to 1953 | John E. Swift | Deputy Supreme Knight[132] Massachusetts State Deputy[133] |

1945[134] to 1949[135] | Timothy Galvin | |||

| 1949[135] to 1960[136] | William J. Mulligan | |||||||

| 10 | September 1, 1953 to February 19, 1964 |  |

Luke E. Hart | Supreme Advocate | ||||

| 1960[136] to 1964[137] | John W. McDevitt[137] | 1961 to 1987 | Charles Pasquale Greco[138][131] | |||||

| 11 | 1964 to 1977 | John W. McDevitt | Deputy Supreme Knight | 1964 to 1966 | John H. Griffin[137][139] | |||

| 1966[140] to April 1976[141] | Charles J. Ducey | |||||||

| 1976 to 1978 | Ernest J. Wolff[141] | |||||||

| 12 | January 21, 1977 to September 30, 2000 | Virgil C. Dechant | Supreme Secretary, Supreme Master | |||||

| 1978[141] to | Frederick H. Pelletier[142] | |||||||

| 1984 to 1997 | Ellis Flynn[143] | |||||||

| 1987 to 2005 | Thomas V. Daily[144] | |||||||

| 1997 to 2000 | Robert F. Wade[145] | |||||||

| 13 | October 1, 2000 to present |  |

Carl A. Anderson | Supreme Secretary, Vice President for Public Policy |

2000 to 2006 | Jean Migneault[146] | ||

| 2005 to present | William Lori[147] | |||||||

| 2006 to 2013 | Dennis Savoie[148][149] | |||||||

| 2013 to 2017 | Logan T. Ludwig[150] | |||||||

| January 1, 2017 to present | Patrick E. Kelly[150] | |||||||

References

Notes

- ↑ For example, the Knights of St. Patrick, the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, the Sons of Erin, the Catholic Order of Foresters, the Red Knights, The Irish Catholic Benevolent Union, the Hibernian Society, the Catholic Benevolent League, the Ancient Order of Foresters, the St. Vincent's Death Benefit League, any number of local parish total abstinence societies.[6]

- ↑ This includes 34,854 knights in 374 college councils, and 2,227 online members.[83]

- ↑ Kennedy, the only Catholic to be elected President of the United States, was a Fourth Degree member of Bunker Hill Council No. 62 and Bishop Cheverus General Assembly. At the meeting, the president told Hart that his younger brother, Ted Kennedy, had received "his Third Degree in our Order three weeks before."[94]

- ↑ Other US insurance groups also downgraded by S&P from AAA to AA+ were New York Life, Northwestern Mutual, TIAA, and USAA as, like the Knights of Columbus, their assets are highly concentrated in the U.S. and they have significant holdings in U.S. Treasury and agency securities.

References

- ↑ "History". Knights of Columbus. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 16.

- ↑ Brinkley & Fenster 2006, p. 51.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, pp. 8-9.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 Koehlinger 2004.

- ↑ Glenn, Brian J. "Rhetoric of Fraternalism: Its Influence on the Development of the Welfare State 1900-1935". Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- ↑ Brinkley & Fenster 2006, pp. 116–117.

- 1 2 "Christopher Columbus – 500 Years Later". Knights of Columbus. 1947. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

By taking the name of Columbus, the Knights were able to remind the entire country of the Catholic roots of the New World, and to highlight the fact that faithful Catholics could also be good citizens ...

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 McGowan 1999, p. 174.

- 1 2 3 4 McGowan 1999, p. 173.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 9.

- 1 2 McGowan 1999, p. 180.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, pp. 32-33.

- 1 2 Brinkley & Fenster 2006, p. 171.

- 1 2 3 "A Diverse Church". The Catholic University of America Archives. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ↑ Skocpol, Ganz & Munson 2000, p. 532.

- ↑ Skocpol, Ganz & Munson 2000, p. 533.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 73.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, pp. 388-389.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 390.

- ↑ McGowan 1999, pp. 174-175.

- ↑ McGowan 1999, p. 175.

- ↑ McGowan 1999, p. 177.

- ↑ Trepanier 2007, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Trepanier 2007, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 Egan & Kennedy 1920, p. 117.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, pp. 137–139.

- ↑ Kauffman 2001, p. 15.

- 1 2 Kauffman 2001, p. 2.

- ↑ Egan & Kennedy 1920, p. 118.

- ↑ Egan & Kennedy 1920, p. 119.

- ↑ Pelowski, Alton J. (June 2014). "Remembering Mr. Blue". Columbia. Knights of Columbia. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- 1 2 "The Life and Legacy of Father Michael J. McGivney" (PDF). Knights of Columbus. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ↑ Young 2015, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Young, Julia G. (23 July 2015). "Smuggling for Christ the King". OUPblog. New York: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ↑ "History of the Knights of Columbus: Priest Martyrs of Mexico" (PDF). Knights of Columbus. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ↑ Meyer 1976.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, pp. 301–302.

- ↑ "A Growing Legacy". Columbia. Vol. 92 no. 8. April 2012. p. 2.

- ↑ Dunne, Susan. "Replica of WWI Trench Commemorates Great War Centennial", Hartford Currant, August 16, 2017

- 1 2 Sweany 1923, p. 2.

- 1 2 Kauffman, Christopher J., "Knights of Columbus", The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia, (Anne Cipriano Venzon, ed.), Routledge, 2013 ISBN 9781135684532

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sweany 1923, p. 3.

- ↑ Scott 1919, pp. 407–408.

- ↑ Appel, Allan. "A Trenchant World War", New Haven Independent, April 20, 2017

- ↑ "Johnny Evers Meets An Old Friend In France". The Milwaukee Journal. August 30, 1918. p. 6. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982.

- 1 2 3 Roberts, Tom (May 15, 2017). "Knights of Columbus' financial forms show wealth, influence". National Catholic reporter. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Dumenil 1991, p. 23.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 349.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, pp. 349–350.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 350.

- ↑ "Peace Program Proposed by the Knights of Columbus" (PDF). Knights of Columbus. 19 August 1943. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 Kauffman 1982, p. 343.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kauffman 1982, p. 344.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, pp. 344-5.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 Dumenil 1991, p. 31.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 171.

- ↑ Egan & Kennedy 1920, p. 120.

- 1 2 Egan & Kennedy 1920, p. 121.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 169.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 276.

- ↑ Fry, Henry Peck (1922). The Modern Ku Klux Klan. Small, Maynard. pp. 109–116.

- ↑ Mecklin, John (April 16, 2013). The Ku Klux Klan: A Study of the American Mind. Read Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-4733-8675-4.

- ↑ "Great & Fake Oath". Time. September 3, 1928. Archived from the original on April 1, 2008. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Kauffman 1982, p. 277.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 278.

- ↑ Egan & Kennedy 1920, p. 122.

- ↑ Egan & Kennedy 1920, p. 127.

- ↑ Dumenil 1991, p. 34.

- ↑ 268 U.S. 510 (1925)

- ↑ "Pierce v. Society of Sisters". University of Chicago Kent School of Law. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, p. 282.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 283.

- ↑ Alley, Robert S. (1999). The Constitution & Religion: Leading Supreme Court Cases on Church and State. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books. pp. 41–44. ISBN 1-57392-703-1.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, pp. 269–270.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 396.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, p. 397.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 400.

- ↑

- 1 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "Annual Report of the Supreme Knight" (pdf). Knights of Columbus. August 6, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. xv.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 388.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 335.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 320.

- ↑ Sweany 1923, p. 1.

- ↑ Egan & Kennedy 1920, p. v.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, p. 152.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 Kauffman 1982, p. 391.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, pp. 393–394.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kauffman 1982, p. 419.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 420.

- ↑ "Venerable Michael McGivney". Father McGivney Guild. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Vatican Declares Knights of Columbus Founder 'Venerable'". Reuters. March 16, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Bush Welcomes Pope With Pomp and Pageantry". U.S. News and World Report. April 16, 2008. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ↑ McClain, Justin (5 June 2017). Our Bishops, Heroes for the New Evangelization: Faithful Shepherds and the Promotion of Lay Doctrinal Literacy. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 89–. ISBN 978-1-4982-8422-6.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 126.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 22.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ "Historical Currency Conversions". Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ↑ Brinkley & Fenster 2006, p. 123.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, pp. 63, 66, 75-76, 78.

- 1 2 3 4 Kauffman 1982, p. 378.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, p. 377.

- ↑ Sullivan, Neil. The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York (Oxford; 2001)

- 1 2 3 4 Sameea Kamal (July 11, 2013). "Knights of Columbus Insurance Program Passes $90 Billion Mark - Courant.com". Hartford Courant. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Fortune 500 – Knights of Columbus". CNN Money. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ↑ Maurer, Charles E., Jr. "Report of the Supreme Secretary". Supreme Council Proceedings One Hundred-Thirtieth Annual Meeting. p. 53.

- ↑ "How to Describe the Benefits of Membership". Knights of Columbus. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Knight of Columbus", Fortune 500

- ↑ "For 38th consecutive year, A.M. Best reaffirms top A++ rating for Knights of Columbus". July 11, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Supreme Knight's Annual Report". Archived from the original on August 6, 2006. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Moody's Backs US's AAA Rating, S&P Cuts Fannie, Others". CNBC. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Rating Actions Taken On 10 U.S.-Based Insurance Groups Following Sovereign Downgrade". Standard & Poor's. August 8, 2011. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 18.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, pp. 40-41.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, p. 61.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 103.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 131.

- 1 2 "National Council, K of C., Increases Issue. Next Convention Will Be Held in Louisville". The Boston Globe. June 4, 1903. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kauffman 1982, p. 287.

- ↑ Dodge 1903, p. 9; Kauffman 1982, p. 114.

- ↑ "History of the Uniontown Council No. 1275". Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ "First Michigan Man to be Elected Supreme Knight". The Augustinian. XXXV (87). Kalamzaoo, Michigan. August 20, 1927. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- 1 2 "K. of C. Pledge support for NRA". The Bulletin. XIV (16). Augusta, Ga. August 26, 1933. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Kauffman 1982, p. 338.

- 1 2 Kauffman 1982, p. 394.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 339.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 359.

- ↑ Kauffman 1982, p. 357.

- 1 2 "Swift Appoints Mulligan Deputy Supreme Knight". The Boston Globe. May 21, 1949. p. 2. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- 1 2 "K. of C Re-elect* Hart Supreme Knight". The Berkshire Eagle. Pittsfield, Massachusetts. October 22, 1960. p. 5. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "HON. JOHN H. GRIFFIN, M.D., K.S.G., K.H.S." (PDF). Knights of Columbus Maryland State Council. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Bishop Charles P. Greco" (pdf). Louisiana Ladies Auxiliary Association. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ↑ Jordan, Robert (March 1, 1964). "New Chief of Knights Led Waltham Schools". The Boston Globe. p. 54. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ↑ "McDevitt is reelected as KC head". New Orleans Clarion Herald. October 27, 1966. p. 2. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Kauffman 1982, p. 417.

- ↑ "Local Delegates at K of C Convention". Hanover Evening Sun. May 21, 1979. p. 14. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ↑ "ORDER MOURNS THE PASSING OF FORMER DEPUTY SUPREME KNIGHT". Knights of Columbus. April 11, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ "KNIGHTS OF COLUMBUS MOURNS THE PASSING OF SUPREME CHAPLAIN EMERITUS". Knights of Columbus. May 15, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Annual Report of Supreme Knight Virgil C. Dechant". Chuck Hauger. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ Anderson, Carl A. (September 11, 2008). "SUPREME KNIGHT'S EULOGY FOR JEAN MIGNEAULT". Knights of Columbus. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ "ARCHBISHOP WILLIAM E. LORI, S.T.D. SUPREME CHAPLAIN OF THE KNIGHTS OF COLUMBUS". Knights of Columbus. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ↑ Gosgnach, Tony (August 30, 2007). "Q and A with: Dennis Savoie". The Interim. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ↑ Gyapong, Deborah (February 27, 2015). "Ambassador settles in to new role in Rome". The B.C. Catholic. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- 1 2 "Patrick E. Kelly". Knights of Columbus. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

Sources

- Alley, Robert S., ed. (1999). The Constitution & Religion: Leading Supreme Court Cases on Church and State. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-703-1.

Bauernschub, John P. (1949). Fifty Years of Columbianism in Maryland. Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland State Council.

- ——— (1965). Columbianism in Maryland, 1897–1965. Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland State Council.

- Brinkley, Douglas; Fenster, Julie M. (2006). Parish Priest: Father Michael McGivney and American Catholicism. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-077684-8.

- Dodge, William Wallace (1903). The Fraternal and Modern Banquet Orator: An Original Book of Useful Helps at the Social Session and Assembly of Fraternal Orders, College Entertainments, Social Gatherings and All Banquet Occasions. Chicago: Monarch Book Company.

- Dumenil, Lynn (Fall 1991). "The tribal Twenties: "Assimilated" Catholics' response to Anti-Catholicism in the 1920s". Journal of American Ethnic History. 11 (1): 21–49.

- Egan, Maurice Francis; Kennedy, John James Bright (1920). The Knights of Columbus in Peace and War. 1. ISBN 978-1-142-78398-3.

- Fry, Henry Peck (1922). The Modern Ku Klux Klan. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- Hearn, Edward (1910). "Knights of Columbus". In Herbermann, Charles G.; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé B.; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. Catholic Encyclopedia. 8. New York: Encyclopedia Press (published 1913). pp. 670–671.

- Kauffman, Christopher J. (1982). Faith and Fraternalism: The History of the Knights of Columbus, 1882–1982. Harper and Row. ISBN 978-0-06-014940-6.

- ——— (1995). "Knights of Columbus". In Venzon, Anne Cipriano; Miles, Paul L. The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing (published 2013). pp. 321–322. ISBN 978-1-135-68453-2.

- ——— (2001). Patriotism and Fraternalism in the Knights of Columbus. New York: Crossroad Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8245-1885-1.

- Kaufmann, Eric P. (2007). The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920848-7.

- Koehlinger, Amy (Winter 2004). ""Let Us Live for Those Who Love Us": Faith, Family, and the Contours of Manhood among the Knights of Columbus in Late Nineteenth-Century Connecticut". Journal of Social History. 38 (2): 455–469. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- Marchildon, Gregory P. (2009). "Introduction". In Marchildon, Gregory P. Immigration and Settlement, 1870–1939. History of the Prairie West. 2. Regina, Saskatchewan: University of Regina Press. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-88977-230-4.

- McGowan, Mark G. (1999). Waning of the Green: Catholics, the Irish, and Identity in Toronto, 1887-1922. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-1789-9.

- Mecklin, John (2013) [1924]. The Ku Klux Klan: A Study of the American Mind. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4733-8675-4.

- Salvaterra, David L. (2002). "Review of Patriotism and Fraternalism in the Knights of Columbus: A History of the Fourth Degree by Christopher J. Kauffman". The Catholic Historical Review. 88 (1): 157–158. doi:10.1353/cat.2002.0048. ISSN 1534-0708. JSTOR 25026129.

- Scott, Emmett J. (1919). Scott's Official History of the American Negro in the World War. Chicago: Homewood Press. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Singular, Stephen (2005). By Their Works: Profiles of Men of Faith Who Made a Difference. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-116145-2.

- Skocpol, Theda; Ganz, Marshall; Munson, Ziad (2000). "A Nation of Organizers: The Institutional Origins of Civic Voluntarism in the United States". The American Political Science Review. 94 (3): 527–546. doi:10.2307/2585829. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- Sullivan, Neil (2001). The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sweany, Mark J. (1923). Educational Work of the Knights of Columbus. Bureau of Education Bulletin. 22. Washington: Government Printing Office. hdl:2346/60378.

- Trepanier, James Daniel Joseph (2007). Battling a Trojan horse: The Ordre de Jacques Cartier and the Knights of Columbus, 1917--1965 (Thesis). University of Ottowa. Retrieved August 21, 2018.