Hiawatha

Hiawatha (also known as Ayenwathaaa, Aiionwatha, or Haiëñ'wa'tha [ha.jẽʔ.waʔ.tha] in Onondaga)[1] was a pre-colonial Native American leader and co-founder of the Iroquois Confederacy. Depending on the version of the narrative, he was a leader of the Onondaga and the Mohawk, or both. According to some versions, he was born an Onondaga, but adopted into the Mohawk.

Hiawatha was a follower of the Great Peacemaker (Deganawida), a Huron prophet and spiritual leader who proposed the unification of the Iroquois peoples, who shared common ancestry and similar languages. The Great Peacemaker was a compelling spiritual presence, but was impeded in evangelizing his prophecy by foreign affiliation and a severe speech impediment. Hiawatha, a skilled and charismatic orator, along with a clan mother named Jigonhsasee, was instrumental in persuading the Senecas, Cayugas, Onondagas, Oneidas and Mohawks to accept the Great Peacemaker's vision and band together to become the Five Nations of the Iroquois confederacy. The Tuscarora nation joined the Confederacy in 1722 to become the Sixth Nation.

Eclipse

In attempting to date the Great Peacemaker and Hiawatha, focus has come to an incident related to the founding of the Iroquois Confederacy, their lifework. One rendition of the oral history eventually written down by scholars involves a division among the Seneca nation, the last nation to join the original confederacy. A violent confrontation began and was suddenly stopped when the sun darkened, and it seemed like night. Scholars have successively studied the possibilities of this being a solar eclipse since 1902 when William Canfield wrote Legends of the Iroquois; told by "the Cornplanter".[2] Successive other scholars who mention it were (chronologically): Paul A. W. Wallace,[3] Elizabeth Tooker,[4] Bruce E. Johansen,[5][6] Dean R. Snow,[7] Barbara A. Mann and Jerry L. Fields,[8] William N. Fenton,[9] David Henige,[10] Gary Warrick,[11] and Neta Crawford.[12]

Since Canfield's first mention,[2] and the majority view,[3][4][7][9][11] scholars have supported the 1451 AD date[13] for the plausible solar eclipse mention. Some argue it is an insufficient fit for the description and favor 1142 AD[5][8][14] while a few question the whole idea.[10]

Archaeological supporting arguments have progressed. In 1982 Dean Snow considered the mainstream view of the archaeology not to support any dates for an eclipse before 1350 AD (thus ruling out the 1142 AD date.)[7] By 1998 Fenton considered an earlier eclipse than the 1451 AD majority view unlikely but possible as long as it was after 1000 AD – a window that allows the 1142 AD date.[9] By 2007/8 reviews considered an 1142 AD eclipse as clearly possible even if most still supported 1451 AD as the safe choice.[11][12]

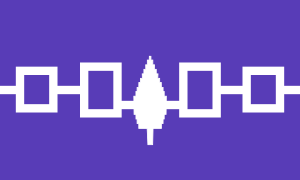

Hiawatha Belt

The Hiawatha Belt is made of 6,574 wampum beads – 38 rows by 173 columns and has 892 white and 5,682 purple beads. The purple represents the sky or universe that surrounds us, while the white represents purity and Good Mind (good thoughts, forgiveness and understanding). The belt symbolizes these Five Nations from west to east in their respective territories across New York state: Seneca (keepers of the western door), Cayuga (People of the Swamp), Onondaga (Keepers of the Fire), Oneida (People of the Standing Stone) and Mohawk (keeper of the eastern door)—by open squares of white beads with the central figure signifying a tree or heart. The white open squares are connected by a white band that has no beginning or end, representing all time now and forever. The band, however, does not cross through the center of each nation, meaning that each nation is supported and unified by a common bond and that each is separate in its own identity and domain. The open center also signifies the idea of a fort protected on all sides, but open in the center, symbolizing an open heart and mind within.

The tree figure signifies the Onondaga Nation, capital of the League and home to the central council fire. It was on the shores of Onondaga Lake where the message of peace was "planted" and the hatchets were buried. From this tree, four white roots sprouted, carrying the message of unity and peace to the four directions.

The Hiawatha Belt has been dated to the mid-18th century. Near its center, it contains a bead made of colonial lead glass. It is believed the design is as old as the league itself, but the present belt is not the original.[15]

The Hiawatha Belt forms the basis of the flag of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, created in the 1980s. It is the central device in the design on the reverse of the U.S. 2010 Native American dollar (also known as the Sacagawea dollar). It is also included in the logo of the Hamilton Nationals, a former Major League Lacrosse team.

Legacy

- Hiawatha Council, former name of the Longhouse Council, BSA in Onondaga County (succeeded by Hiawatha-Seaway Council after merger with Seaway Valley Council)

- Hiawatha Boulevard is a street in Syracuse NY, in Onondaga County.

- Hiawatha Lake, in Onondaga Park in Syracuse, NY

- In 1950, plans for a film about the historical Hiawatha by Monogram Pictures were scrapped. The reason given was that Hiawatha's peacemaker role could be seen as communist propaganda.[16][17]

- A film was released in 1997 based on the Longfellow poem. It was a joint production of the U.S. and Canada, filmed in Ontario, Canada.[18]

- The 26.66-mile (42.91 km) Hiawatha bike trail in northern Idaho and Montana is over a former railroad right-of-way on old bridges and through old tunnels.[19]

- A 52-foot (16 m) tall, 16,000 lb (7,300 kg) fiberglass statue of Hiawatha was built in 1964 and stands in Ironwood, MI. It is billed as the "World's Tallest and Largest Indian".[20]

- Hiawatha National Forest is a 894,836-acre (362,127 ha) National Forest in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

- Amtrak, a railroad serving the continental United States and parts of Canada, has a train called "Hiawatha Service", which runs several times daily between Chicago, IL and Milwaukee, WI.[21] It was named for a series of trains formerly operated by the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad.

- The Metro Blue Line in Hennepin County, Minnesota was formerly known as the Hiawatha Line. The line runs largely along its namesake Hiawatha Avenue in Minneapolis.

- The Island of Hiawatha is the former name of the Toronto Islands.[22]

- Hiawatha appears as a playable leader for the Iroquois in the video games Sid Meier's Civilization III and Sid Meier's Civilization V.

- Hiawatha Elementary School in Essex Jct. VT.

- Hiawatha Park, Chicago Park District park, northwest City of Chicago

- Hiawatha Beach neighborhood was established in 1926. These homes surround Buck Lake and line the Huron River in Hamburg Township, MI.

- The Links at Hiawatha Landing. A golf course in Appalachian, NY.

See also

- The Song of Hiawatha, which includes the fictitious Aboriginal woman Minnehaha

Notes

- ↑ Bright, William (2004). Native American Place Names of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-3576-X pg. 166

- 1 2 William W. Canfield (1902). The Legends Of The Iroquois: Told By "The Cornplanter". A. Wessels Co. pp. 219–220.

- 1 2 Wallace, Paul A. W. (October 1948). "The Return of Hiawatha". New York History Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association. XXIX (4): 385–403. JSTOR 23149546.

- 1 2 Elizabeth Tooker (1978). "The League of the Iroquois: Its History, Politics, and Ritual". In Sturtevant, William; Trigger, Bruce. Handbook of North American Indians. Government Printing Office. pp. 418–41. GGKEY:0GTLW81WTLJ.

- 1 2 Johansen, Bruce (1979). Franklin, Jefferson and American Indians: A Study in the Cross-Cultural Communication of Ideas (Thesis). University of Washington. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ↑ Bruce Elliott Johansen (January 1982). Forgotten Founders: How the American Indian Helped Shaped Democracy. Harvard Common Press. ISBN 978-0-916782-90-0.

- 1 2 3 Snow, Dean R. (September 1982). "Dating the Emergence of the League of the Iroquois: A Reconsideration of the Documentary Evidence" (PDF). Historical Archeology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Rensselaerswijck Seminar. V: 139–144. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- 1 2 Barbara A. Mann; Jerry L. Fields (1997). "A Sign in the Sky: Dating the League of the Haudenosaunee". American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 21 (4): 105–163. ISSN 0161-6463. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- 1 2 3 William Nelson Fenton (1998). The Great Law and the Longhouse: A Political History of the Iroquois Confederacy. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-8061-3003-3.

- 1 2 Henige, David (1999). "Can a Myth Be Astronomically Dated?". American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 23 (4): 127–157. ISSN 0161-6463. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Gary Warrick (2007). "Precontact Iroquoian Occupation of Southern Ontario". In Jordan E. Kerber. Archaeology of the Iroquois: Selected Readings and Research Sources. Syracuse University Press. pp. 124–163. ISBN 978-0-8156-3139-2.

- 1 2 Neta Crawford (15 April 2008). "The Long Peace among Iroquois Nations". In Kurt A. Raaflaub. War and Peace in the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 348–. ISBN 978-0-470-77547-9.

- ↑ Jubier, F. Espenak and Xavier. "NASA - Total Solar Eclipse of 1451 June 28". eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ↑ Jubier, F. Espenak and Xavier. "NASA – Total Solar Eclipse of 1142 August 22". eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ↑ "Proceedings", American Philosophical Society (vol. 115, No. 6, p. 446)

- ↑ Wallechinsky, David (1975). The People's Almanac. Garden City: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04060-1. p. 239

- ↑ "Digital History: Post-War Hollywood". uh.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-11-29.

- ↑ The Song of Hiawatha film https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120163/?ref_=nm_flmg_dr_1

- ↑ "Route of the Hiawatha (Official Website) > The Trail". www.ridethehiawatha.com.

- ↑ Hiawatha statue description from Roadside America http://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/11874

- ↑ Amtrak Route Hiawatha Retrieved 2013-5-3

- ↑ "Toronto Historic Maps". peoplemaps.esri.com.

Further reading

- Bonvillain, Nancy (2005). Hiawatha : founder of the Iroquois Confederacy. ISBN 1-59155-176-5 ISBN 9781591551768

- Hale, Horatio (1881). Hiawatha and the Iroquois confederation : a study in anthropology.

- Hatzan, A. Leon (1925). The true story of Hiawatha, and history of the Six Nations Indians.

- Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe (1856). The Myth of Hiawatha, and Other Oral Legends, Mythologic and Allegoric, of the North American Indians.

- Laing, Mary E. (1920). The hero of the longhouse.

- Saraydarian, Torkom and Joann L Alesch (1984). Hiawatha and the great peace. ISBN 0-911794-25-5 ISBN 9780911794250 ISBN 0-911794-28-X ISBN 9780911794281

- Siles, William H. (1986). Studies in local history : tall tales, folklore and legend of upstate New York.

Juvenile audience

- Bonvillain, Nancy (1992). Hiawatha : founder of the Iroquois Confederacy. ISBN 0-7910-1707-9 ISBN 9780791017074

- Fradin, Dennis B. (1992). Hiawatha : messenger of peace. ISBN 0-689-50519-1 ISBN 9780689505195

- McClard, Megan, George Ypsilantis and Frank Riccio (1989). Hiawatha and the Iroquois league. ISBN 0-382-09568-5 ISBN 9780382095689 ISBN 0-382-09757-2 ISBN 9780382097577

- Malkus, Alida (1963). There really was a Hiawatha.

- St. John, Natalie and Mildred Mellor Bateson (1928). Romans of the West : untold but true story of Hiawatha.

- Taylor, C. J. (2004). Peace walker: the legend of Hiawatha and Tekanawita. ISBN 0-88776-547-5 ISBN 9780887765476

External links

- Historica’s Heritage Minute Peacemaker, a mini-docudrama about the co founders of the Iroquois Confederacy.

- Chapter V, The Iroquois Confederacy

- History of the Mohawk Valley: Dekanawida and Hiawatha, Schenectady Digital History Archive

- Google Books overview of Ancient Society

- The Great Peacemaker Deganawidah and his follower Hiawatha, theater play by Living Wisdom School

- Hiawatha at Find a Grave