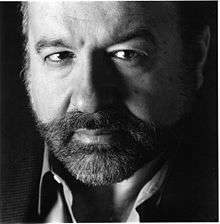

Hernando de Soto Polar

| Hernando de Soto Polar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

June 3, 1941 Arequipa, Peru |

| Nationality | Peruvian |

| Field |

The economics of the informal sector, research in property rights theory |

| School or tradition |

Austrian School Chicago School |

| Influences |

Milton Friedman Friedrich Hayek |

| Contributions | Dead capital |

Hernando de Soto Polar (or Hernando de Soto; born 1941) is a Peruvian economist known for his work on the informal economy and on the importance of business and property rights. He is the president of the Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD), located in Lima, Peru.[1]

Early life and education

De Soto was born on 2 June 1941 in Arequipa, Peru. His father was a Peruvian diplomat. After the 1948 military coup in Peru, his parents chose exile in Europe, taking their two young sons with them. De Soto was educated in Switzerland, where he attended the International School of Geneva and then did post-graduate work at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva. He later worked as an economist, corporate executive and consultant. He returned to Peru at the age of 38.[2] His younger brother Álvaro served in the Peruvian diplomatic corps in Lima, New York City and Geneva and was seconded to United Nations in 1982. He retired from the U.N. in 2007 with the title rank of Assistant Under-Secretary-General; his last position was as the UN Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process.[3] He is well known as an international adviser.

Reforms in Peru and elsewhere

Between 1988 and 1995, he and the Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD) were mainly responsible for some four hundred initiatives, laws, and regulations that led to significant changes in Peru's economic system.[4]

In particular, ILD designed the administrative reform of Peru's property system which has given titles to an estimated 1.2 million families and helped some 380,000 firms, which previously operated in the black market, to enter the formal economy.[5] This latter task was accomplished through the elimination of bureaucratic "red-tape" and of restrictive registration, licensing and permit laws, which made the opening of new businesses very time-consuming and costly.

Yale University political scientist Susan C. Stokes believe that de Soto's influence helped change the policies of Alberto Fujimori from a Keynesian to a neoliberal approach. De Soto convinced then-president Fujimori to travel to New York City, where they met with Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, Barber Conable, Enrique V. Iglesias (the heads of the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and the Inter-American Development Bank), who convinced him to follow the guidelines for economic policy set by the international financial institutions.[6] These policies led to a reduction in the rate of inflation.[7]

The Cato Institute and The Economist magazine have argued that de Soto's policy prescriptions brought him into conflict with and eventually helped to undermine the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso) guerrilla movement. By granting titles to small coca farmers in the two main coca-growing areas, they argued that the Shining Path was deprived of safe havens, recruits and money, and the leadership was forced to cities where they were arrested.[8][9] A large terrorist attack was launched against the ILD and de Soto in light of the statements by Shining Path leader Abimael Guzmán who saw ILD as a serious threat.[10][11]

After the split with Fujimori, he and his institute designed similar programs in El Salvador, Haiti, Tanzania, and Egypt and has gained favor with the World Bank, the World Bank-allied international NGO Slum Dwellers International and the government of South Africa.

Since its work in Peru in the 1980s, his institute, the ILD, has worked in dozens of countries. Heads of state in over 35 countries have sought the ILD's services to discuss how ILD's theories on property rights could potentially improve their economies.[12]

The impact of de Soto's institute in the field of development—on political leaders, experts and multi-lateral organizations—is widespread and acknowledged. For example:

- The ILD's institutional reform program has attracted the interest of strategically key nations concerned with internal conflict and terrorism.

- The ILD has designed successful reforms that have inspired major initiatives in former client countries such as Egypt, the Philippines, Honduras and Tanzania.

- The ILD is recognized as the world authority in understanding extralegal economies, influencing the protocols of large multilateral organizations by helping them to understand the realities that the poor and the excluded face, day to day. These include institutions such as the Commission for Legal Empowerment of the Poor, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), USAID and the World Bank.[13]

In 2009, the ILD turned its attention back to Peru and the plight of the indigenous peoples of the Peruvian Amazon jungle. In response to Peru's President García's call to all Peruvians to present their proposals toward solving the problems leading to the bloody incidents in Bagua, the ILD has assessed the situation and presented its preliminary findings. ILD has published a short videotaped documentary, The Mystery of Capital among the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon, summarizing its findings from indigenous communities in Alaska, Canada and the Peruvian jungle.[14]

Main thesis

The main message of de Soto's work and writings is that no nation can have a strong market economy without adequate participation in an information framework that records ownership of property and other economic information.[15] Unreported, unrecorded economic activity results in many small entrepreneurs who lack legal ownership of their property, making it difficult for them to obtain credit, sell the business, or expand. They cannot seek legal remedies to business conflicts in court, since they do not have legal ownership. Lack of information on income prevents governments from collecting taxes and acting for the public welfare.

The existence of such massive exclusion generates two parallel economies, legal and extra legal. An elite minority enjoys the economic benefits of the law and globalization, while the majority of entrepreneurs are stuck in poverty, where their assets—adding up to more than US$10 trillion worldwide—languish as dead capital in the shadows of the law.[16]

To survive, to protect their assets, and to do as much business as possible, the extralegals create their own rules. But because these local arrangements are full of shortcomings and are not easily enforceable, the extralegals also create their own social, political and economic problems that affect the society at large.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, responsible nations around the developing world have worked hard to make the transition to a market economy, but have in general failed.[17] Populist leaders have used this failure of the free market system to wipe out poverty in the developing world to beat their "anti-globalization" drums. But the ILD believes that the real enemy is within the flawed legal systems of developing nations that make it virtually impossible for the majority of their people—and their assets—to gain a stake in the market. The people of these countries have talent, enthusiasm, and an astonishing ability to wring a profit out of practically nothing`.[16]

What the poor majority in the developing world do not have is easy access to the legal system which, in the advanced nations of the world and for the elite in their countries, is the gateway to economic success, for it is in the legal system where property documents are created and standardized according to law. That documentation builds a public memory that permits society to engage in such crucial economic activities as identifying and gaining access to information about individuals, their assets, their titles, rights, charges and obligations; establishing the limits of liability for businesses; knowing an asset's previous economic situation; assuring protection of third parties; and quantifying and valuing assets and rights.[18] These public memory mechanisms in turn facilitate such opportunities as access to credit, the establishment of systems of identification, the creation of systems for credit and insurance information, the provision for housing and infrastructure, the issue of shares, the mortgage of property and a host of other economic activities that drive a modern market economy.[19]

Work and research

Since 2008, De Soto has been refining his thesis about the importance of property rights to development in response to his organization’s findings that a number of new global threats have "property rights distortions" at their root. In essays, that appeared from early 2009 into 2012 in media outlets in the U.S. and Europe, De Soto argued that the reason why the U.S. and European economies were mired in recession was the result of a "knowledge crisis" not a financial one.[20][21][22][23][24]

"Capitalism lives in two worlds," De Soto wrote in the Financial Times in January 2012. "There is the visible one of palm trees and Panamanian ships, but it is the other – made up of the property information cocooned in laws and records – that allows us to organize and understand fragments of reality and join them creatively."[25] De Soto argued that the knowledge in those public memory systems, which "helped Capitalism triumph," was distorted over the past 15 years or so. "Until this knowledge system is repaired," he wrote, "neither US nor European capitalism will recover." [26]

In another series of articles that appeared in US and Europe in 2011, De Soto used the findings of ILD field research in Egypt, Tunisia and Libya to make his case for "the economic roots of the Arab Spring."[27][28][29] The ongoing Arab revolutions, he argued, were "economic revolutions" driven mainly by the frustrations of 200 million ordinary Arabs who depended on the informal economy for their livelihoods.[28][29] He pointed to the ILD’s earlier 2004 findings in Egypt, which revealed the nation’s largest employer with 92% of the property in the informal economy – assets worth almost $247 billion.[27][30] Also, as proof of the extent of desperation among MENA’s entrepreneurs, he elaborated ILD’s exclusive research on Mohamed Bouazizi, the Tunisian street vendor whose public self-immolation in protest of the expropriation of his goods and scale literally sparked the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia, which spread unrest through the Arab world.[31][32][33]

After losing core funding from USAID, ILD laid off the majority of their employees from their San Isidro office. In 2014-2015, De Soto and a small team working out of his house began to attempt to guide the political process in Peru, as Presidential elections were due to take place in 2016, by finding solutions to the ongoing national mining crisis. De Soto has been a strong advocate for the formalisation of the informal miners that are scattered throughout Peru.[34][35] Since 2014, several large national investment projects, including Las Bambas, and Tia Maria have been disrupted by violent protests by informal miners against government regulation and formal extractive industries.[36] In July 2015, the ILD discovered that former Shining Path militants who have taken up the ecological cause were paralyzing some $70 billion in mining investment in Peru.[37]

Furthermore, recorded video debates between the former extremists and De Soto were published on ILD’s YouTube channel and revealed that the Shining Path militants agree that property rights could be an important part of the solution to social conflicts in Peru.[38] De Soto’s stated goal is to determine the roots of informal hostility against multinationals and identify what is needed to build a national social contract on extractive industries that could harmonize their property interests with those of multinationals as opposed to creating conflict.[37]

De Soto applies thesis to terrorism

In October 2014, De Soto published an article in the Wall Street Journal, The Capitalist Cure for Terrorism, that stated an aggressive agenda for economic empowerment was needed in the Middle East in order to defeat terrorist groups like ISIL. He argued that the U.S. should promote an agenda similar to what was successfully used in Peru to defeat the Shining Path in the 1990s.[39] He also mentions in the article that local policymakers in the Middle East are missing the fact that if ordinary people cannot play the game legally, they will be far less able to resist a terrorist offensive. The article received praise among high-level global politicians such as US Presidential candidates Rand Paul and Jeb Bush.[40][41]

Once again In January 2016, De Soto released his second article, How to Win the War on Terror, which focused on defeating terrorism through promoting strong property rights.[42] The article was distributed by Project Syndicate and published in dozens of countries and languages, including in Switzerland by the World Economic Forum in advance of their 2016 forum.[43][44]

De Soto challenges Thomas Piketty and approaches Pope Francis

In 2014, De Soto started to refute French economist Thomas Piketty’s thesis by arguing that his recent attacks against capital in his worldwide best seller book "Capital in the 21st Century" were unjustified.[45] His op-ed article challenging Piketty, ‘The Poor Against Piketty’ (French - Les pauvres contre Piketty) was first published in France’s news magazine Le Point in April 2015.[46]

De Soto argued that Piketty’s statistics ignore the 90 per cent of the world population that lives in developing countries and former Soviet states, whose inhabitants produce and hold their capital in the informal sector.[47] Furthermore, he states that his institute’s global research proves that most people actually want more rather than less capital. Finally, he argues that the wars against capital, which Piketty claims are coming, have already begun under Europe’s nose in the form of the Arab Spring in the Middle East and North Africa.[48] The article in English was published in The Independent under the title, ‘Why Thomas Piketty is wrong about capital in the 21st century’, in May 2015 and has since been published in over twenty countries, including in Germany’s Die Welt,[49] Nigeria's Ventures Africa,[50] Spain's El Pais,[51] Egypt's Youm 7 [52] and Brazil's Folha de S.Paulo,[53] Canada's Vancouver Sun [54] and the Miami Herald.[55]

In February 2016, De Soto took a break from countering Piketty’s work and wrote an article addressing Pope Francis’s trip to Mexico titled, A Mexican Impasse for the Pope.[56] The article encourages the Pope and the Vatican to address the lack of property rights among the poor in countries like Mexico as a solution to global refugee crises.[57][58]

A week later, De Soto published a second article in Fortune Magazine addressing the Pope’s and US Republican Presidential candidate Donald Trump’s public spat over building a wall on the Mexican-USA border. The article titled, What Pope Francis Should Really Say to Donald Trump, conveys five property rights related thoughts that the Pope should use to respond to Trump.[59] The article was well received in the US and led to many different opinion articles featured in Breitbart, Investors Business Daily and Stream.[60][61]

Blockchain work

In May 2015, De Soto attended the 1st Annual Block Chain Summit hosted by British billionaire Richard Branson at his private Caribbean residence, Necker Island.[62][63] De Soto was one of three moderators, along with Michael J. Casey, former Wall Street Journal senior columnist and Matthew Bishop, editor at The Economist. Advocates of blockchain technology argue that it is well-suited to acting as a public ledger to help achieve De Soto's objective of formalising the informally-held property rights of groups like the indigenous peoples of Peru[64][65][66][67][68]

De Soto presented a property application of Bitcoin to Sheikh Nahyan bin Mubarak Al Nahyan of the United Arab Emirates and financial authorities of Abu Dhabi at a second Blockchain summit held in Abu Dhabi in 2015.[69]

De Soto has since been involved with a land titling project in Georgia which uses blockchain technology as a notary service.[70]

Praise for work

Since the publication of The Mystery of Capital in 2000 and subsequent translations, his ideas have become increasingly influential in the field of development economics.

Time magazine chose De Soto as one of the five leading Latin American innovators of the century in its special May 1999 issue "Leaders of the New Millennium", and included him among the 100 most influential people in the world in 2004.[71] De Soto was also listed as one of the 15 innovators "who will reinvent your future" according to Forbes magazine's 85th anniversary edition. In January 2000, Entwicklung und Zusammenarbeit, the German development magazine, described De Soto as one of the most important development theoreticians.[72] In October 2005, over 20,000 readers of Prospect magazine of the UK and Foreign Policy magazine of the U.S. ranked him as number 13 on the joint survey of the world's Top 100 Public Intellectuals Poll.

U.S. presidents from both major parties have praised De Soto's work. Bill Clinton, for example, called him "The world's greatest living economist",[73] George H. W. Bush declared that "De Soto's prescription offers a clear and promising alternative to economic stagnation…"[74] Bush's predecessor, Ronald Reagan said, "De Soto and his colleagues have examined the only ladder for upward mobility. The free market is the other path to development and the one true path. It is the people's path… it leads somewhere. It works."[75] His work has also received praise from two United Nations secretaries general Kofi Annan – "Hernando de Soto is absolutely right, that we need to rethink how we capture economic growth and development"[76] – and Javier Pérez de Cuéllar – "A crucial contribution. A new proposal for change that is valid for the whole world."[77]

In October 2016, de Soto was honored with the Brigham-Kanner Property Rights Prize, awarded by the William & Mary Law School during the 13th Annual Brigham-Kanner Property Rights Conference, in recognition of his tireless advocacy of property rights reform as a tool to alleviate global poverty.[78]

Prizes

Among the prizes he has received are:

- The Freedom Prize (Switzerland)

- The Fisher Prize (United Kingdom)

- 2002

- the Goldwater Award (USA)

- Adam Smith Award from the Association of Private Enterprise Education (USA)

- The CARE Canada Award for Outstanding Development Thinking (Canada)

- 2003

- received the Downey Fellowship at Yale University

- the Democracy Hall of Fame International Award from the National Graduate University (USA)

- 2004

- the Templeton Freedom Prize (USA)

- the Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty (USA)[8]

- the Royal Decoration of the Most Admirable Order of the Direkgunabhorn, 5th Class, (Thailand)

- 2005

- an honorary Doctor of Letters from the University of Buckingham (United Kingdom),

- The Americas Award (USA)

- named the Most Outstanding of 2004 for Economic Development at Home and Abroad by the Peruvian National Assembly of Rectors

- received the Prize of Deutsche Stiftung Eigentum for exceptional contributions to the theory of property rights

- the 2004 IPAE Award by the Peruvian Institute of Business Administration

- the Academy of Achievement's Golden Plate Award 2005 (USA) in tribute to his outstanding accomplishments

- the BearingPoint, Forbes magazine's seventh Compass Award for Strategic Direction

- was named as a "Fellow of the Class of 1930" by Dartmouth College.

- 2006

- the 2006 Bradley Prize for outstanding achievement by the Bradley Foundation.[79]

- the 2006 Innovation Award (Social and Economic Innovation) from The Economist magazine (December 2, 2006) for the promotion of property rights and economic development.[80]

- 2007

- The Poder BCG Business Awards 2007, granted by Poder Magazine and the Boston Consulting Group, for the "Best Anti-Poverty Initiative"

- the anthology Die Zwölf Wichtigsten Ökonomen der Welt (The World's Twelve Most Influential Economists, 2007), included a profile of de Soto among a list that begins with Adam Smith and includes such recent winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics as Joseph Stiglitz and Amartya Sen.

- the 2007 Humanitarian Award in recognition of his work to help poor people participate in the market economy.

- 2009

- Honorary patron of the University Philosophical Society of Trinity College, Dublin for having excelled in public life and made a worthy contribution to society.

- the inaugural Hernando de Soto Award for Democracy awarded by the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) in recognition of his extraordinary achievements in furthering economic freedom in Peru and throughout the developing world.[81]

- 2010

- the Hayek Medal for his theories on liberal development policy ("market economy from below") and for the appropriate implementation of his concepts by two Peruvian presidents.

- the Medal of the Presidency of the Italian Republic (Council of Ministers) in recognition of his contribution toward the betterment of humankind and having worked for the future of the earth through his commitment.

- 2016

- received the 2016 Brigham–Kanner Property Rights Prize from William & Mary Law School during a ceremony in The Hague, Netherlands, in October 2016.[82]

World Justice Project

Hernando de Soto serves as an honorary co-chair for the World Justice Project. The World Justice Project works to lead a global, multidisciplinary effort to strengthen the rule of law for the development of communities of opportunity and equity.[83]

Criticism and responses

Over the last decades, property rights literature has voiced diverse views on the effect of the titling of land.[84][85][86][87][88][89] De Soto has been criticized by some academics for methodological and analytical reasons, while some activists have accused him of just wanting to be a representative figure of the prioritizing property rights movement. Some state that his theory does not offer anything new compared to traditional land reform. "De Soto’s proposal is not wealth transfer, but wealth legalization. The poor of the world already possess trillions in assets now. De Soto is not distributing capital to anyone. By making them liquid, everyone’s capital pool grows dramatically".[90] While analysing Schaefer’s arguments, Roy writes, "de Soto’s ideas are seductive precisely because they only guarantee the latter, but in doing so promise the former".[91]

What differentiates de Soto from his predecessor is his attempt to include non-agricultural land in the scheme of reform and emphasizing in formalization of existing informal possession.[92] His emphasis on title formalization as the only reason behind economic growth in the United States has been subject to criticism.[93] Property formalization in America may have happened as a result of different reasons including establishment of law and order, increased state control, greater institutional integration, increased economic efficiency, increased tax revenue, and greater equality.([92]) The argument for private and often individualist property regime comes under the question of societal legitimacy, may not be justified even if de Soto eyes bringing an unified system in a state or unification with the global economy.[90]

In his 'Planet of Slums'[94] Mike Davis argues that de Soto, who Davis calls 'the global guru of neo-liberal populism', is essentially promoting what the statist left in South America and India has always promoted—individual land titling. Davis argues that titling is the incorporation into the formal economy of cities, which benefits more wealthy squatters but is disastrous for poorer squatters, and especially tenants who simply cannot afford incorporation into the fully commodified formal economy.

Grassroots controlled and directed shack dwellers movements like Abahlali baseMjondolo in South Africa and the Homeless Workers' Movement (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto – MTST) in Brazil[95][96] have strenuously argued against individual titling and for communal and democratic systems of collective land tenure because this offers protection to the poorest and prevents 'downward raiding' in which richer people displace squatters once their neighborhoods are formalized.

An article by Madeleine Bunting for The Guardian (UK) claimed that de Soto's suggestions would in some circumstances cause more harm than benefit, and referred to The Mystery of Capital as "an elaborate smokescreen" used to obscure the issue of the power of the globalized elite. She cited de Soto's employment history as evidence of his bias in favor of the powerful.[97] Reporter John Gravois also criticized de Soto for his ties to power circles, exemplified by his attendance at the Davos World Economic Forum. In response, de Soto told Gravois that this proximity to power would help de Soto educate the elites about poverty. Ivan Osorio of the Competitive Enterprise Institute has refuted Gravois's allegations pointing out how Gravois has misinterpreted many of de Soto's recommendations.[98]

Robert J. Samuelson has argued against what he sees as de Soto's "single bullet" approach and has argued for a greater emphasis on culture and how local conditions affect people's perceptions of their opportunities.[99] UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Olivier De Schutter, has questioned the insistence on titling as a means to protect security of tenure based on the risk that titling will undermine customary forms of tenure and insufficiently protect the rights of land users that depend on the commons, as well as the fear that titling schemes may lead to further reconcentration of land ownership, unless strong support is provided to smallholders.

In the World Development journal, a 1990 article by R. G. Rossini and J. J. Thomas of the London School of Economics questioned the statistical basis of de Soto's claims about the size of the informal economy in his first book The Other Path.[100] However, the ILD pointed out, in the same journal, that Rossini and Thomas’ observations "neither [addressed] the central theme of the book, nor [did it address] the main body of quantitative evidence displayed to substantiate the importance of economic and legal barriers that give rise to informal activities. Instead, [they focused] exclusively on four empirical estimates that the book [mentioned] only in passing".[101]

In the Journal of Economic Literature, Christopher Woodruff of the University of California, San Diego criticized de Soto for overestimating the amount of wealth that land titling now informally owned property could unlock, and argues that "de Soto's own experience in Peru suggests that land titling by itself is not likely to have much effect. Titling must be followed by a series of politically challenging steps. Improving the efficiency of judicial systems, rewriting bankruptcy codes, restructuring financial market regulations, and similar reforms will involve much more difficult choices by policymakers."[102][103]

Empirical studies by Argentine economists Sebastian Galiani and Ernesto Schargrodsky have taken issue with de Soto's link between titling and the increase in credit to the poor, but have also pointed out that families with titles "substantially increased housing investment, reduced household size, and improved the education of their children relative to the control group".[104] A study commissioned by DFID, an agency of the U.K. government, further summarized many of the complications arising from implementing de Soto's policy recommendations when insufficient attention is paid to the local social context.[105]

De Soto himself has often pointed out that his critics mistakenly claim that he advocates land titling by itself as sufficient for effective development: For example, in the ILD's new brochure he is quoted as saying, "The ILD is not just about titling. What we do is help Governments build a system of public memory that legally identifies all their people, their assets, their business records and their transactions in such a way that they can unleash their economic potential. No economy can develop and prosper without the benefits that clearly registered public documents bestow."[106]

On January 31, 2012, de Soto and his publisher were fined by the Peruvian intellectual property rights organization INDECOPI for excluding the names of co-authors, Enrique Ghersi and Mario Ghibellini, on newer editions of his 1986 book The Other Path.[107][108][109][110]

Publications

Books

De Soto has published two books about economic development: The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World in 1986 in Spanish (with a new edition in 2002 titled The Other Path, The Economic Answer to Terrorism) and in 2000, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else ( ISBN 978-0465016150). Both books have been international bestsellers, translated into some 30 languages.

The original Spanish-language title of The Other Path is El Otro Sendero, an allusion to de Soto's alternative proposals for development in Peru, countering the attempts of the "Shining Path" ("Sendero Luminoso") to win the support of Peru's poor. Based on five years worth of ILD research into the causes of massive informality and legal exclusion in Peru, the book was also a direct intellectual challenge to the Shining Path, offering to the poor of Peru not the violent overthrow of the system but "the other path" out of poverty, through legal reform. In response, the Senderistas added de Soto to their assassination list. In July 1992, the terrorists sent a second car bomb into ILD headquarters in Lima, killing 3 and wounding 19.

In addition, he has written, with Francis Cheneval, Swiss Human Rights Book Volume 1: Realizing Property Rights, published in 2006 – a collection of papers presented at an international symposium in Switzerland in 2006 on the urgency of property rights in impoverished countries for small business owners, women, and other vulnerable groups, such as the poor and political refugees. The book includes a paper on the ILD's work in Tanzania delivered by Hernando de Soto.[111]

- De Soto, Hernando. The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World. Harpercollins, 1989. ISBN 0-06-016020-9

- De Soto, Hernando. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. Basic Books, 2000. ISBN 0-465-01614-6

- De Soto, Hernando. The Other Path: The Economic Answer to Terrorism. Basic Books, 2002. ISBN 0-465-01610-3

- De Soto, Hernando and Francis Cheneval. Swiss Human Rights Book Volume 1: Realizing Property Rights, 2006. ISBN 978-3-907625-25-5

- Smith, Barry et al. (eds.). The Mystery of Capital and the Construction of Social Reality, Chicago: Open Court, 2008. ISBN 0-8126-9615-8

Articles

De Soto has also published a number of articles on the importance of inclusive property and business rights, legally empowering the poor, and the causes of the global financial crisis of 2008–09 in leading newspapers and magazines around the world. In 2001, Time magazine published "The Secret of Non-Success,"[112] the New York Times ran his post-September 11 op-ed essay "The Constituency of Terror,"[113] and the IMF's Finance & Development magazine published "The Mystery of Capital", a condensed version of the third chapter of his eponymous book.[114] In 2007, Time magazine published "Giving the Poor their Rights", an article written with former Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, on the legal empowerment of the poor. In 2009, Newsweek International published his essay on the financial crisis, "Toxic Paper"[115] – along with an on-line interview with him, "Slumdogs and Millionaires."[116] That was soon followed by two more articles on the crisis, in the Wall Street Journal ("Toxic Assets Were Hidden Assets")[117] and The Los Angeles Times ("Global Meltdown Rule #1: Do the Math").[118] Versions of these articles also appeared in newspapers in France, Switzerland, Germany and Latin America. In 2011, Bloomberg published "The Destruction of Economic Facts",[119] and The Washington Post recently ran "The cost of financial ignorance".[120] When protests began in Cairo at the beginning of 2011, The Wall Street Journal published De Soto's "Egypt's Economic Apartheid",[121] and Financial Times later published "The free-market secret of the Arab Revolution".[122]

See also

References

- ↑ Institute for Liberty and Democracy, "Hernando de Soto – Detailed Bio". (accessed 16 March 2013)

- ↑ Source: Investors Business Daily, Monday November 6, 2006. p. A4. Leaders & Success. Article by IBD Reinhardt Kraus.

- ↑ (PDF) http://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-files/Guardian/documents/2007/06/12/DeSotoReport.pdf. Retrieved 31 August 2015. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ The Globalist | Biography of Hernando de Soto Archived 2006-09-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill - Website Maintenance". www.johnstoncenter.unc.edu. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Times, Paul Lewis and Special To the New York. "NEW PERU LEADER IN ACCORD ON DEBT". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Stokes, Susan. "Are Parties What's Wrong with Democracy in Latin America?".

- 1 2 "Hernando de Soto's Biography". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "The economist versus the terrorist". The Economist. 30 January 2003.

- ↑ http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB64/peru33.pdf

- ↑ "The Other Path". www.ild.org.pe. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "Achievements". www.ild.org.pe. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2015-07-17.

- ↑ Enrique Escalante, Edwar. "Peru: The Mystery of Capital among the Indigenous People of the Amazon". Hacer Latin America. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Destruction of Economic Facts", by Hernando de Soto. April 28, 2010. Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Accessed online May 2, 2011

- 1 2 de Soto, Hernando. 2000. The Mystery of Capital. UK: Black Swan.

- ↑ de Soto 2000, 1

- ↑ Barry Smith, ""Searle and De Soto: The New Ontology of the Social World", in Barry Smith, David Mark and Isaac Ehrlich (eds.), The Mystery of Capital and the Construction of Social Reality, Chicago: Open Court, 2008, 35–51.

- ↑ Institute for Liberty and Democracy, The ILD's war against exclusion, p. 19. 2009

- ↑ Sheridan, Barrett. "Economy: Slumdogs vs. Wall Street Millionaires". Newsweek. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Destruction of Economic Facts". Bloomberg Business. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "Toxic Assets Were Hidden Assets". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "What if you can't prove you had a house?". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Knowledge Crisis Strategy". ild.org.pe. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "Knowledge lies at the heart over western capitalism". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "Knowledge lies at the heart of western capitalism". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- 1 2 "The Secret to Reviving the Arab Spring's Promise: Property Rights". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- 1 2 "The free market secret of the Arab revolution". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- 1 2 "The real Mohamed Bouazizi". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Economic Roots of the Arab Spring". Council of foreign relations. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Real Mohamed Bouazizi". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "Economic Inclusion, Democracy, and the Arab Spring". CIPE Development. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "Arab Spring unrest was ignited by entrepreneurs facing constraints: Economist". Daily News Egypt. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "Juliaca: Hernando de Soto propondrá formalización a mineros". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Gestión, Redacción (11 July 2015). "Hernando de Soto propone hacer a las comunidades accionistas de las mineras". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "Conga, Tía María y Las Bambas". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- 1 2 Balbi, Mariella (5 July 2015). "De Soto: "Hay US$70 mil mlls. de inversión minera paralizada"". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Institute for Liberty and Democracy (8 July 2015). "Hernando de Soto Y Anti-Mineros (Segmento #1)". Retrieved 16 August 2018 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Soto, Hernando de (10 October 2014). "The Capitalist Cure for Terrorism". Retrieved 16 August 2018 – via www.wsj.com.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-11-25. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ↑ "Rand Paul on ISIS, Benghazi and Bringing U.S. Troops Home". 11 December 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "How to win the war on terror". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "This is how we can win the war on terror". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Tiempo, Casa Editorial El. "Cómo ganarle la guerra al terrorismo / Análisis". El Tiempo. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "Hernando de Soto refuted the theories of Thomas Piketty". El Comercio Portfolio. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ magazine, Le Point, (2015-04-16). "Les pauvres contre Piketty". Le Point (in French). Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "Why Thomas Piketty is wrong about capital in the 21st century". The Independent. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Canoy, Marcel. "Why De Soto owns Piketty". Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "Die Armen der Welt sind viel reicher als gedacht". Die Welt. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Poor Against Piketty". Venture Africa. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "Los pobres frente a Piketty". El Pais. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ Youm 7 http://www.youm7.com/story/2015/5/3/90-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%B3%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85-%D9%8A%D8%AD%D8%AA%D9%81%D8%B8%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A8%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%88%D9%84%D9%87%D9%85-%D8%A8%D8%B9%D9%8A%D8%AF%D8%A7-%D8%B9%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A5%D8%AD%D8%B5%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B1%D8%B3%D9%85%D9%8A/2165688#.Vb6QdpNVikq. Retrieved 2 August 2015. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "The poor against Piketty". Folha. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ Soto, Hernando de. "Opinion: The poor against Piketty". www.vancouversun.com. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "Hernando De Soto dissects Thomas Piketty's apocalyptic political thesis". miamiherald. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ Soto, Hernando de (11 February 2016). "A Mexican Impasse for the Pope - by Hernando de Soto". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Pope and property rights". 15 February 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "Helping those without rights to step out of the shadows". 12 February 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "What Pope Francis Should Really Say to Donald Trump". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Daily, Investor's Business (2016-02-19). "Pope Francis Keeps Listening To The Wrong Peruvian". Investor's Business Daily. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "Pope Francis and Economist Hernando de Soto Agree on One Thing: Free the Poor by Protecting Their Property Rights | The Stream". The Stream. 2016-02-17. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ Bitfury. "Block Chain Summit". www.blockchainsummit.io. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ admin (16 June 2015). "Shaping serendipity". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ https://www.cnbc.com/2015/07/01/venture-capitalist-bill-tai-my-summer-reading-list-commentary.html.

- ↑ Casey, Michael J. "BitBeat: Grand Plans for Bitcoin From Necker Island". WSJ. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "CULMINA CUMBRE QUE REÚNE A LAS MENTES MÁS BRILLANTES DEL MUNDO". Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "Techonomy Report - Techonomy Magazine 2015". www.ifoldsflip.com. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "Could blockchain technology help the world's poor?". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ Brad, Kamloops. "De Soto Speaks at a Block Chain Summit in Abu Dhabi". ild.org.pe. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ Prisco, Giulio. "BitFury Announces Blockchain Land Titling Project With the Republic of Georgia and Economist Hernando De Soto". Bitcoin Magazine. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- ↑ "The 2004 TIME 100 - TIME". TIME.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Hans-Heinrich Bass und Markus Wauschkuhn: Hernando de Soto – die Legalisierung des Faktischen, in: E+Z Entwicklung und Zusammenarbeit, 2000, Nr. 1, S. 15–18. Archived 2013-07-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "UNC News release -- Noted economist de Soto to discuss property rights". www.unc.edu. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Source for President George H. W. Bush's remarks: Text of Remarks by the President to the World Bank/International Monetary Fund Annual Meeting, 27 September 1989, announcing NAFTA. Press release.

- ↑ "Praise for de Soto and Institute for Liberty and Democracy". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "TRANSCRIPT OF PRESS CONFERENCE BY SECRETARY-GENERAL KOFI ANNAN AT INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION, GENEVA, 16 JULY 2001 - Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". www.un.org. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "Penguin Books". www.booksattransworld.co.uk. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "William & Mary Law School - Internationally Renowned Peruvian Economist de Soto Honored at 13th Property Rights Conference". law.wm.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- ↑ Bradley Foundation – Prizes Archived 2010-07-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Search". The Economist. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "CIPE @ 25". cipe.advomation.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "William & Mary - Hernando de Soto to receive 2016 Brigham-Kanner Property Rights Prize". www.wm.edu. Retrieved 16 August 2018. line feed character in

|title=at position 15 (help) - ↑ "About". Archived from the original on 2010-02-03. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- ↑ Bruce, J., Migot-Adholla, S. (Eds.), 1994. Searching for Land Tenure Security in Africa. Kendall Hunt, Dubuque.

- ↑ Sjaastada, Espen and Ben Cousins. 2008. "Formalisation of Land Rights In the South: An Overview." Land Use Policy 26: 1–9

- ↑ Gilbert, Alan. 2002. On the mystery of capital and the myths of Hernando de Soto. What difference does legal title make? International Development Planning Review 24 (1) 1–19.

- ↑ Pinckney, T.C. and P.K. Kimuyu. 1994. "Land Tenure Reform in East Africa: Good, Bad or Unimportant?" Journal of African Economies 3 (1): 1–28.

- ↑ Platteau, J.-P. 1996. "The Evolutionary Theory of Land Rights as Applied To Sub-Saharan Africa: A Critical Assessment." Development and Change 27 (1): 29–85.

- ↑ Deininger, Klaus. 2003. Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- 1 2 "Dey Biswas, Sattwick. 2014. Land Rights Formalization in India; Examining de Soto through the lens of Rawls theory of justice. FLOOR Working paper 18" (PDF). Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Roy, Dayabati. 2013. Rural Politics in India: Political Stratification and Governance in West Bengal. Cambridge University Press, pp 152

- 1 2 Sjaastada, Espen and Ben Cousins. 2008. "Formalisation of Land Rights In the South: An Overview." Land Use Policy 26: 1–9.

- ↑ Madrick, Jeff. 2001. The Charms of Property. The New York Review of Books

- ↑ Mike Davis, Planet of Slums, Verso, 2006 pp. 79–82

- ↑ MTST – Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto Archived 2008-07-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Home - Friends of the MST". www.mstbrazil.org. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Bunting, Madeleine (11 September 2000). "Fine words, flawed ideas". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Osorio, Ivan. Will the Real Hernando de Soto Please Stand Up?, originally published as Osorio Op-ed in Tech Central Station, February 2, 2005". Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ↑ Samuelson, Robert J (January–February 2001). "The Spirit of Capitalism". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008.

- ↑ Rossini, R. G. and J. J. Thomas. "The size of the informal sector in Peru: A critical comment on Hernando de Soto's El Otro Sendero", in World Development, Volume 18, Issue 1, January 1990, pp. 125–35.

- ↑ "A reply". World Development. 18 (1): 137–145. 1 January 1990. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(90)90108-A. Retrieved 16 August 2018 – via www.sciencedirect.com.

- ↑ Woodruff, Christopher. Review: Review of de Soto's "The Mystery of Capital", Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Dec., 2001), pp. 1215–23

- ↑ "Clift, Jeremy. "People in Economics: Hernando de Soto" – Finance & Development – December 2003" (PDF). Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Galiani, Sebastian and Ernesto Schargrodsky. Property Rights for the Poor: Effects of Land Titling – Ronald Coase Institute, Working Paper Series, revised January 2009,

- ↑ "Daley, Elizabeth and Mary Hobley. Land: Changing Contexts, Changing Relationships, Changing Rights (for DFID's Urban-Rural Change Team) September 2005". Archived from the original on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ↑ Institute for Liberty and Democracy, The ILD's war against exclusion, p. 21. 2009

- ↑ "Perú: Condenan por infracción a derecho moral de paternidad a economista Hernando de Soto". IP Tango: weblog for intellectual property law and practice for Latin America. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ http://elcomercio.pe/economia/peru/sancionan-hernando-soto-violacion-propiedad-intelectual-noticia-1368239

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2015-07-17.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- ↑ De Soto, Hernando and Francis Cheneval. Swiss Human Rights Book Volume 1: Realizing Property Rights, 2006. Archived 2008-11-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Investment, Global Forum on International (1 January 2002). "New Horizons for Foreign Direct Investment". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved 16 August 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Soto, Hernando De. "The Constituency of Terror". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "Finance and Development". Finance and Development - F&D. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "Hernando de Soto on the Toxic-Paper Problem". 20 February 2009. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "Economy: Slumdogs vs. Wall Street Millionaires". 19 February 2009. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Soto, Hernando de (25 March 2009). "Toxic Assets Were Hidden Assets". Retrieved 16 August 2018 – via www.wsj.com.

- ↑ Soto, By Hernando de. "Global Meltdown Rule No. 1: Do the math". latimes.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "De Soto, Hernando. "The Destruction of Economic Facts", Bloomberg Businessweek, 28 April 2011". Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ "The cost of financial ignorance". Washington Post. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Soto, Hernando de (3 February 2011). "Egypt's Economic Apartheid". Retrieved 16 August 2018 – via www.wsj.com.

- ↑ "Subscribe to read". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

External links

- Institute for Liberty and Democracy official website.

- "Slumdogs vs. Millionaires", Newsweek's Barrett Sheridan interviews Hernando de Soto

- The Great Issues Forum, video of Naomi Klein, Joseph Stiglitz, and Hernando de Soto discussing the financial crisis

- "Mapping the Invisible", speech by Hernando de Soto at the 2009 ESRI International User Conference

- The Munk Debate on Foreign Aid, 2009. Stephen Lewis and Paul Collier against Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto and Dambisa Moyo, a Zambian-born critic of foreign aid.

- Afternoon of Conversation: Andrea Mitchell, Madeleine Albright, Hernando De Soto, video of conversation

- The Rule of Law – an interview with Hernando de Soto By Gustavo Wensjoe 2008

- Transcript of an interview for the PBS documentary Commanding Heights.

- A highly critical review in the British newspaper The Guardian

- An essay by Robert Samuelson in Foreign Affairs, arguing that de Soto underestimates the importance of culture

- The Power of the Poor – Documentary about de Soto's work by Free to Choose Media

- Appearances on C-SPAN