Hans Kammler

| Hans Kammler | |

|---|---|

NSDAP ID photograph, 1932 | |

| Born |

26 August 1901 Stettin, German Empire |

| Died |

9 May 1945 (aged 43) near Prague |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ | SS |

| Rank | SS-Obergruppenführer und General der Waffen-SS |

| Commands held | Office D within the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office |

Hans Kammler (26 August 1901 – 9 May 1945) was a German civil engineer and SS commander during the Nazi era. He oversaw SS construction projects and towards the end of World War II was put in charge of the V-2 missile and jet programmes.

Early life

Kammler was born in Stettin, German Empire (now Szczecin, Poland). In 1919, after volunteering for army service, he served in the Rossbach Freikorps. From 1919 to 1923, he studied civil engineering at the Technische Hochschule der Freien Stadt Danzig and Munich and was awarded his Dr.-Ing. in November 1932, following some years of practical work in local building administration.[1]

Kammler joined the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in 1931[2] and held a variety of administrative positions after the Nazi government came to power in 1933, initially as head of the Aviation Ministry's building department. He joined the SS (no. 113,619) on 20 May 1933. In 1934, he was a councillor for the Reich's Interior Ministry.

In 1934, he also was the leader of the Reichsbund der Kleingärtner und Kleinsiedler (Reich's federation of small gardeners and landowners).[3]

World War II

In June 1941, Kammler joined the Waffen-SS.[2]

Kammler eventually became Oswald Pohl's deputy at the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (WVHA). He oversaw Office D (administration of the concentration camp system), and was also Chief of Office C, which designed and constructed all the concentration and extermination camps. In this latter capacity he oversaw the installation of more efficient cremation facilities at Auschwitz-Birkenau as part of the camp's conversion to an extermination camp.[4][5]

Role on advanced weapon projects

Before the beginning of World War II, there are no indications that Kammler was involved in any advanced engineering projects apart from his educational background. Also, in the early years of the war nothing suggests his involvement in any weapons projects.

Clear links between Kammler and advanced weapon projects seem to appear only in 1942. Early evidence of this is a letter from Oswald Pohl to Heinrich Himmler referring an interdepartmental memorandum on the manufacturing of modern weapons in concentration camps, having Kammler as one of the participants.

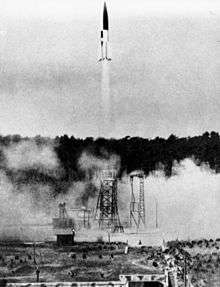

Kammler was also charged with constructing facilities for various secret weapons projects, including manufacturing plants and test stands for the Messerschmitt Me 262 and V-2. Following the Allied bombing raids on Peenemünde in Operation Hydra, in August 1943, Kammler assumed responsibility for the construction of mass-production facilities for the V-2.[2] He started moving these production facilities underground, which resulted in the Mittelwerk facility and its attendant concentration camp complex, Mittelbau-Dora, which housed slave labour for constructing the factory and working on the production lines. The project was pushed ahead under enormous time pressures despite the consequences for the slave laborers employed on it. Kammler's motto at the time was reportedly, "Don't worry about the victims. The work must proceed ahead in the shortest time possible".[6]

During this period, Kammler also was involved in the attempt to finish the Blockhaus d'Éperlecques known also as the Watten Bunker, a rather unsuccessful project to create a fortified V-2 launch base.

Albert Speer made Kammler his representative for "special construction tasks", expecting that Kammler would commit himself to working in harmony with the ministry's main construction committee. But in March 1944 Kammler had Göring appoint him as his delegate for "special buildings" under the fighter aircraft programme, which made him one of the war economy's most important managers, and robbed Speer of much of his influence.[7]

Final years

After the Reich's failure to attain a victory against USSR, Kammler started to answer for an ever-growing amount of projects, most of them related to construction and engineering. Concentration camps, means of mass extermination, factories, labor management, underground facilities of various purposes, and tank construction were some of the hallmarks of his early years in the SS hierarchy. As far as it is known, he also directly supervised several project bureaus and had direct contact with some of the best engineers of the Reich (e.g. Ferdinand Porsche). As a person, he was characterized by one of his subordinates as intelligent, a pure workaholic, completely given to his work, with a fanatic rhythm and demanding the same from everyone else.

In 1944, Himmler convinced Adolf Hitler to put the V-2 project directly under SS control, and on 8 August Kammler replaced Walter Dornberger as its director. From 31 January 1945, Kammler was head of all missile projects.[2] During this time he also partially answered for the operational use of the V-2 against the Allies, until the moment the war front reached Germany's borders. As an SS officer, Kammler was the last person in Nazi Germany to be appointed to the rank of SS-Obergruppenführer.[8]

In March 1945, partially under the advice of Goebbels, Hitler gradually stripped Goering of several powers on aircraft support as well as maintenance and supply while transferring them to Kammler. This culminated, in the beginning of April, by Kammler being raised to "Fuehrer's general plenipotentiary for jet aircraft".[7]

In late March 1945 Kammler was responsible for ordering his ZV2 division to execute 200 men, women and children (forced labourers and their families) after his car was held up on a crowded road in the Sauerland. Kammler felt Germans were under some "vague threat" from them as they trudged eastwards to escape the Allied bombing. "This riffraff ought to be eliminated" was his reported comment (The German War - N Stargardt - p517).

On 1 April 1945, Kammler ordered the evacuation of 500 missile technicians to the Alps. Since the last V-2 on the western front had been launched in late March, on 5 April Kammler was charged by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht to command the defence of the Nordhausen area. However, rather than defend the missile construction works, he immediately ordered the destruction of all the "special V-1 equipment" at the Syke storage site. What exactly this order implied is unclear.[2]

Death

Preuk statement

On 9 July 1945, Kammler's widow petitioned to have him declared dead as of 9 May 1945. She provided a statement by Kammler's driver, Kurt Preuk, according to which Preuk had personally seen "the corpse of Kammler and been present at his burial" on 9 May 1945. The District Court of Berlin-Charlottenburg ruled on 7 September 1948 that his death was officially established as 9 May 1945.[2]

In a later sworn statement on 16 October 1959, Preuk stated that Kammler's date of death was "about 10 May 1945", but that he did not know the cause of death. On 7 September 1965, Heinz Zeuner (a wartime aide of Kammler's), stated that Kammler had died on 7 May 1945 and that his corpse had been observed by Zeuner, Preuk and others. All the eyewitnesses consulted were certain that the cause of death was cyanide poisoning.[9] In their accounts of Kammler's movements Preuk and Zeuner claimed that he left Linderhof near Oberammergau on 28 April 1945 for a tank conference at Salzburg and then went to Ebensee (where tank tracks were manufactured). According to Preuk and Zeuner he then travelled back from Ebensee to visit his wife in the Tyrol region, when he gave her two cyanide tablets. The next day, 5 May, at around 4 am, he is said to have departed Tyrol for Prague.[2]

Wernher von Braun, also at the time at Oberammergau, later reported having overheard a discussion between Kammler and his aide-de-camp in which Kammler said he planned to hide in nearby Ettal Abbey. Kammler and his followers then left town, according to Braun.[2] Further evidence of Kammler's activities is a telegraph from Kammler to Speer, Himmler and Göring of 16 April, informing them of the creation of a "message centre" at Munich and the appointment of a chief representative for the construction of the Messerschmitt Me 262. On 20 April, he reportedly arrived with a group of technicians at Himmler’s Kommandostelle near Salzburg. On 23 April, Kammler sent a radio message to his office manager at Berlin, ordering him to organize the immediate destruction of the "V-1 equipment near Berlin" and then to go to Munich.[2] In late April/early May, Kammler was reportedly at the Villa Mendelssohn at Ebensee, site of one of the projects assigned to him. On 4 May, he ordered the immediate transfer of the Ebensee office to Prague.[2]

Preuk and Zeuner maintained their version of events through the 1990s, when interviewed by the journalist Kristian Knaack. Some support for this version of events came from letters written by Ingeborg Alix Prinzessin zu Schaumburg-Lippe, a female member of the SS-Helferinnenkorps to Kammler’s wife in 1951 and 1955. In these, she affirmed that Kammler had said goodbye to her on 7 May 1945 in Prague, stating that the Americans were after him, had made him offers but that he had refused and that they would not "get him alive".[2]

Prague

Author Bernd Ruland, in his 1969 book Wernher von Braun: Mein Leben für die Raumfahrt, reports an altogether different account of Kammler's death. According to Ruland, Kammler arrived in Prague by aircraft on 4 May 1945, following which he and 21 SS men defended a bunker against an attack by more than 500 Czech resistance fighters on 9 May. During the attack, Kammler's aide-de-camp Sturmbannführer Starck shot Kammler to prevent him from falling into enemy hands.[10] This version can reportedly be traced to Walter Dornberger, who in turn is said to have heard it from eyewitnesses.[11]

Post-war search for Kammler

US occupation forces conducted various inquiries into Kammler’s whereabouts, beginning with the headquarters of 12th Army ordering a complete inventory of all personnel involved in missile production on 21 May 1945. This resulted in the creation of a file for Kammler, stating that he was possibly in Munich. The CIC noted that he had been seen shortly prior to the arrival of US troops in Oberjoch.[12]

The Combined Intelligence Objectives Sub-Committee (CIOS) in London ordered a search for him in early July 1945. 12th Army replied that he was last seen on 8 or 9 April in the Harz region. In August, Kammler's name made "List 13" of the UN for Nazi war criminals. Only in 1948 did the CIOS receive the information that Kammler reportedly fled to Prague and had committed suicide. Original blueprints of Kammler’s major projects were later found in the personal property of Samuel Goudsmit, the scientific leader of the Alsos Mission.[12]

In 1949 a report written by one Oskar Packe on Kammler was filed by the US Denazification office in Hesse. The report stated that Kammler had been arrested by US troops on 9 May 1945 at the Messerschmitt works at Oberammergau. However, Kammler and some other senior SS personnel had managed to escape in the direction of Austria or Italy. Packe disbelieved the reports about a suicide, as these were "refuted by the detailed information from the CIC" about arrest and escape.[12]

A CIC report from April 1946 listed Kammler among SS officers known to be outside Germany and considered to be of special interest to the CIC. In mid-July 1945, the head of the Gmunden CIC office, Major Morrisson interviewed an unnamed German on the issue of a numbered account associated with construction sites for plane and missile production formerly run by the SS. A report published years later, in late 1947 or early 1948, stated that only Kammler and two other persons had access to the account. The report also said that "shortly after the occupation, Hans Kammler appeared at CIC Gmunden and gave a statement on operations at Ebensee".[13] The CIC notes on the interview give no name, but the interviewee must have been one of the three people with access to the account. Aside from Kammler, one was known to have left Austria in May 1945, the other was in a POW camp during July.[12]

Finally, Donald W. Richardson (1917-1997) a former OSS special agent involved in the Alsos Mission, claimed to be "the man who brought Kammler to the US".[13] Shortly before he died, Richardson reportedly told his sons about his experience during and after the war, including Operation Paperclip. According to them, Richardson claimed to have supervised Kammler until 1947. Kammler was supposedly "interned at a place of maximum security, with no hope, no mercy and without seeing the light of day until he hanged himself".[12]

Possible last documented independent testimonies

A purported section of a wartime diary, relating to the surrender of the mountain resort town Garmisch-Partenkirchen to Allied troops, mentions Kammler and his staff.[14] According to this account, Kammler and what the author refers to as his staff of some 600 people, with "good quality" cars and trucks arrived in Oberammergau (north of Garmisch-Partenkirchen) on 22 April 1945. This arrival had been badly received and the local authorities had several arguments with Kammler himself. These conflicts are mentioned in the entries for 23 and 25 April. The last reference, implicating only Kammler's "staff", comes on the night of 28 April – an Oberleutnant Burger reports that they had gone on the same night that American forces began storming Oberammergau, forcing their way to Garmisch and Austria.[15]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Tooze 2007, p. 209.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Karlsch 2014, p. 52.

- ↑ "Blut- und Bodenideologie – die Landesgruppe Sachsen im Reichsbund der Kleingärtner und Kleinsiedler Deutschlands (1933–1945) (German)" (PDF).

- ↑ van Pelt 2002, p. 209.

- ↑ Post 2004.

- ↑ Bornemann & Broszat 1970, p. 165.

- 1 2 Kroener 2003, p. 390.

- ↑ Dienstalterslisten der SS, NSDAP Revised edition (20 April 1945)

- ↑ Naasner 1998, p. 341.

- ↑ Ruland 1969, p. 292.

- ↑ Piszkiewicz 2007, p. 215.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Karlsch 2014, p. 53.

- 1 2 "La fuga segreta del custode dell'atomica nazista - la Repubblica.it". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ↑ Gais 1945.

- ↑ Utschneider 2000.

Sources

- Agoston, Tom (1985). Blunder!: How the U.S. Gave Away Nazi Supersecrets to Russia. Dodd, Mead. ISBN 0-396-08556-3.

- Bornemann, Manfred; Broszat, Martin (1970). "Das KL Dora-Mittelbau". Studien zur Geschichte der Konzentrationslager. Schriftenreihe der Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (in German). Stuttgart. 21: 154–198. doi:10.1524/9783486703627.154. ISBN 978-3-486-70362-7.

- Farrell, Joseph P. (2005). Reich of the Black Sun: Nazi Secret Weapons & the Cold War Allied Legend. Adventures Unlimited Press. ISBN 1-931882-39-8.

- Gais, Huber (15 May 1945). "Ein Kriegsende - Garmisch-Partenkirchen in den letzten Apriltagen 1945". Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Karlsch, Rainer (2014). "Was wurde aus Hans Kammler? (summary of an article in Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft, Heft 6, 2014)". Frankfurter Allgemeine am Sonntag (in German). Frankfurt: 52–53.

- Kroener, Bernhard R (2003). Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources 1942 – 1944/5. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820873-1.

- Naasner, Walter (1998). SS-wirtschaft und SS-verwaltung (in German). Droste. ISBN 3-7700-1603-3.

- Piszkiewicz, Dennis (2007). The Nazi Rocketeers: Dreams of Space and Crimes of War. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3387-8.

- Post, Bernhard (16 December 2004). "80,000 Cremation Capacity Per Month Not Sufficient for Auschwitz – New Document". The Holocaust History Project. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Ruland, Bernd (1969). Wernher von Braun: Mein Leben fur die Raumfahrt (in German). Offenburg: Burda Verlag.

- Tooze, Adam (2007). The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03826-8.

- Utschneider, Ludwig (2000). "Rüstungsindustrie in Oberammergau im Zweiten Weltkrieg" (in German). Historical Society of Oberammergau. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- van Pelt, Robert Jan (2002). The Case for Auschwitz: Evidence From the Irving Trial. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34016-0.